I am (still) conducting an ongoing review of the seven-part AppleTV+ miniseries Manhunt, named after the Lincoln assassination book by James L. Swanson. This is my historical review for the sixth episode of the series “Useless.” This analysis of some of the fact vs. fiction in this episode contains spoilers. To read my reviews of other episodes, please visit the Manhunt Reviews page.

Episode 6: Useless

At the Garrett farm, Julia Garrett is concerned about her absent father finding her alone with Booth and Herold. She tells the men they have to spend the night in the tobacco barn, and no amount of flirting by Booth is able to shake her resolve. Once inside the barn, Julia locks the men in, leading Herold to immediately fear the worst. Booth, meanwhile, is unphased and tells stories to Herold in an attempt to convince him that he has been through worse scrapes than this.

Back at the Star Hotel in Bowling Green, Secretary Stanton is being cared for by a doctor after the recent collapse that prevented him from riding off with the 16th New York Cavalry. Eddie Stanton and Thomas Eckert lament the toll the manhunt has taken on Stanton and worry about the Secretary’s health.

After another interlude between Booth and Herold in the barn, the 16th NY come riding up to the Garrett house. At the point of Boston Corbett’s gun, Julia Garrett admits that the fugitives are hiding in the tobacco barn and produces the key. Booth and Herold see some cavalrymen approaching the barn and debate opening fire when the barn door is opened. Everton Conger and Luther Baker step partly inside and order the men to surrender.

Booth refuses to surrender and instead offers to settle things with a duel. Baker tells the men that they have five minutes to come out or else he will force them out. The barn door is closed again. Booth fruitlessly attempts to break through the back wall, all while cursing at Herold for being useless to him.

Outside the barn, Corbett offers to attack the barn alone in order to draw Booth’s fire. Conger reminds Corbett that they have all survived the war and that he will not lose another man now. He then orders the other soldiers to lay brush around the barn. The barn is then lit on fire, much to the chagrin of Julia Garrett.

Inside the barn, Herold decides to give up. Booth opens the door and proclaims Davy innocent of the assassination saying that he alone planned it and made his escape. Herold exits the barn and is immediately tied to a tree, while Booth remains inside the smoke-filled barn.

In Bowling Green, Eckert comes into Stanton’s room with the news that Booth will not surrender and that the cavalry is smoking him out. Despite his still weakened condition, Stanton insists on heading out to the Garrett farm to see that Booth’s capture is done right. Stanton, Eckert, and Eddie head out en route to the Garrett farm.

Even though the barn continues to burn, Booth refuses to come out. Conger approaches David Herold and asks him to go back into the barn and convince Booth to surrender. Davy finds a coughing and weakened Booth, who has seemingly accepted his fate to go out in a blaze. Davy pleads with Booth to live, even if it is only one more day. Booth appears to agree, and Davy helps lift him up.

On the outside of the barn, Boston Corbett discovers a small hole and peers through it at the men inside. Davy leads Booth towards the door of the barn when Corbett aims his pistol through the hole and fires, striking Booth and causing him to collapse. Davy turns to Booth and announces that he has been shot. Conger and Baker pull Booth from the barn as Booth deliriously states that Jefferson Davis will save him. Corbett appears, stating that Booth was about to shoot, so he fired first. Herold screams that this is a lie as Corbett looks to the heavens in amazement for having become God’s instrument.

Booth is moved further away from the flames and placed on the porch of the Garrett house. Though Julia Garrett does not want him inside, she still provides a pillow for his head and laments that a “great man deserves the hospital.” The soldiers state that Booth won’t survive the hour. Booth spits up blood, makes a few statements, and dies.

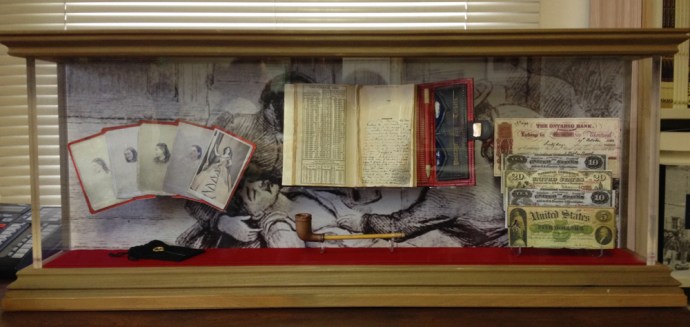

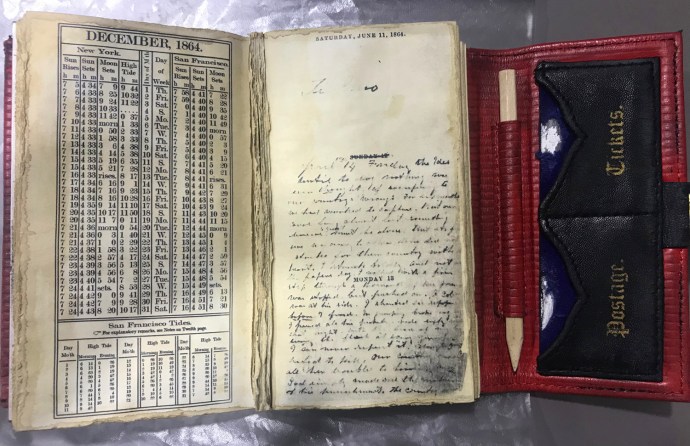

The next scene shows Stanton’s arrival at the Garrett farm after daybreak. Luther Baker apologizes to the Secretary for not taking Booth alive but repeats Corbett’s story that Booth was about to fire. Stanton is led to Booth’s body, which is wrapped in a blanket and lying on a cart. He pulls the blanket off of Booth’s face and sees his quarry face-to-face for the first time. Everton Conger appears and shows Stanton all of the items found on Booth, including his diary, which piques the Secretary’s interest. After Eddie covers Booth’s face back up, Stanton orders Eddie to have Booth’s body fully identified by a coroner and then disposed of in a place that even he doesn’t know.

We then cut to the White House, where Stanton and Judge Advocate Holt prepare to inform President Johnson of their plan to try the remaining assassination conspirators using a military tribunal rather than a civilian court. Johnson is in favor of the idea. Stanton also announces his intention to formally charge Confederate president Jefferson Davis with Lincoln’s death, drawing an uncomfortable look from Holt. President Johnson agrees but tells Stanton he better be able to prove it.

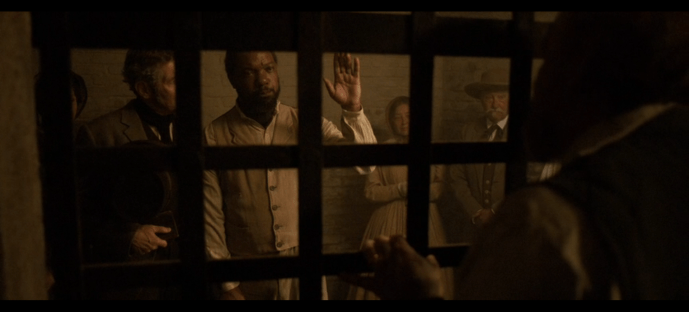

The hunt is then on for crucial witnesses to be used in the trial. In Bryantown, Oswell Swann refuses Luther Baker’s request to testify, countering with, “Talk to me when I’m considered more than three-fifths a man.” From Dr. Mudd’s cell, he pleads with his visiting neighbors to testify on his behalf and tell of his good deeds as a neighbor. Later, Edwin Stanton meets with Mary Simms at a freedmen’s camp in Arlington, telling her how important her testimony would be against Dr. Mudd.

At the War Department, Holt and Eckert express their doubts to Stanton about their ability to prove a grand conspiracy plot against Lincoln involving Jefferson Davis, George Sanders, and the Confederate government. They beg Stanton to reconsider, but he refuses, saying that the trial is his call. A visit to David Herold, looking for a connection to something bigger, proves fruitless. There is a scene showing the capture and arrest of Jefferson Davis and a discussion in the War Department about how to share it with the press.

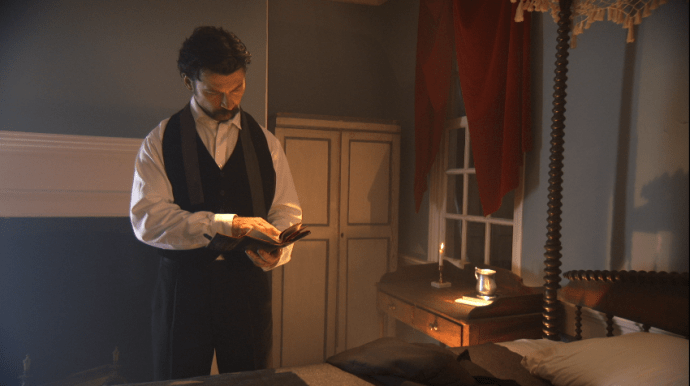

Near the end of the episode, Eddie Stanton informs his father that the inquest over Booth’s body is finished. Before departing with Luther Baker, Eddie notices his father reading Booth’s diary and inquires about it. The Secretary tells his son not to worry about it and dismisses him to his task. Once alone in the room, Stanton tears pages from Booth’s diary and throws them into the fire.

The episode ends with the Secretary announcing his readiness to prepare the next witness, while Eddie Stanton and Luther Baker are shown disposing of three bodies.

Here are some of the things I enjoyed about this episode:

- The Final Dream

This episode opens with a dream sequence that shows Edwin Stanton walking up to Booth’s horse as it grazes in a wood. The Secretary is moving slowly with a pistol drawn and cocked. As he approaches a large tree, Stanton puts his ear close to it before his mouth turns into a wide smile. As we rotate around the tree, we see Booth on the other side, with a revolver in his hand, but his face showing signs of concern. The scene ends with the dreamer, Booth, waking up in bed at the Garrett house. This is the third episode to begin with a dream sequence. Episode 2 started with Stanton dreaming of stopping Booth at Ford’s Theatre. While successful in the dream, the assassin reacted to Stanton’s punches by laughing in the Secretary’s face. In episode 3, Booth dreamed of his ascendance to the Presidency of the Confederacy. His swearing-in ceremony was interrupted by real-life Oswell Swann, who quickly brought Booth out of his fantasy. It’s interesting how the dream in this episode is so different than the ones that came before. Booth is no longer in control or wrapped up in his own glory. Here, near the end, Booth’s dream tells him how closely tracked he truly is. His unconscious mind is telling him the end is near, even if he doesn’t want to accept it. Just a scene later, he reassures Davy that their success is assured and that a night in a barn is nothing. But that is his ego talking. Booth’s subconscious appears to know the truth. I enjoyed all three dream sequence openings.

- Booth and Henrietta

This episode pleasantly surprised me for a bit during Booth and Herold’s time locked in the Garrett barn. Immediately after the title sequence rolls, we see Davy banging on the locked barn door like a caged animal, convinced that the pair are done for. Booth, still ignoring his subconscious mind, assures Davy that he’s gotten out of worse scrapes. To prove his point, Booth shows off a scar on his left cheek. He tells Herold the wound was given to him by a “dancer by the name of Henrietta,” who attacked him with a knife after she found Booth in bed with her sister.

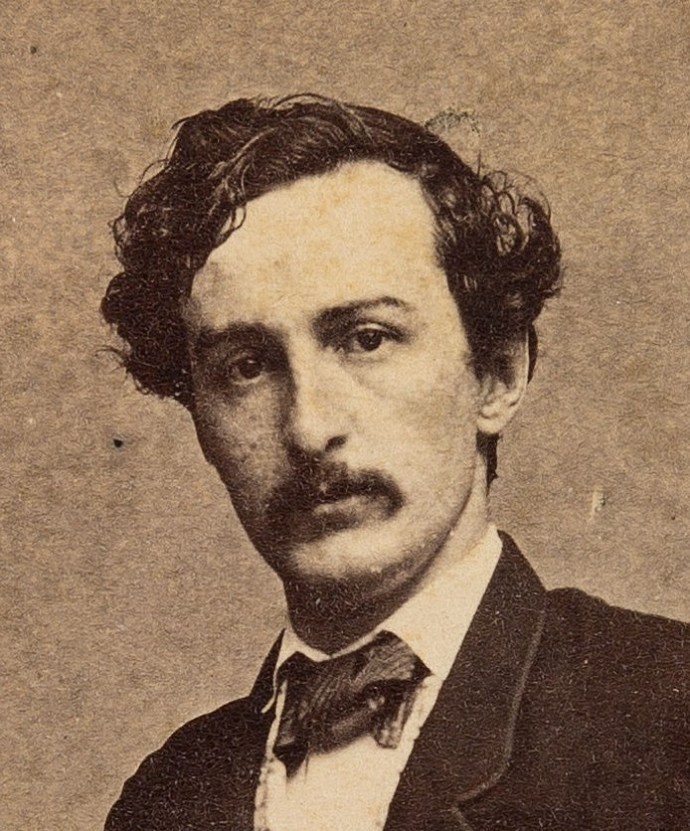

This is a true story of an event that occurred on April 26, 1861, exactly four years prior to the events in the Garrett barn. The 1860-61 theatrical season marked JWB’s first tour as a leading star actor. Theater manager Matthew Canning acted as Booth’s agent and started him in the Southern states before moving north to New York in January of 1861. After arriving in Rochester, Booth met his leading lady for the engagement, an actress by the name of Henrietta Irving.

Five years older than Booth, Henrietta was a native of New York and said to be a niece of author Washington Irving of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” fame. I have tried to verify this with genealogical records but haven’t been able to prove it. Still, there may have been some family connection. Henrietta made her stage debut in 1855. Now six years into her career, Henrietta wasn’t a big household name but was still an accomplished working actress. Henrietta was most appreciated in smaller-sized cities across the country that were bereft of true “star” power. She played the leading parts well and wasn’t above playing supporting roles or sharing billing.

In 1859, Henrietta’s younger sister, Marie, made her debut on the stage. When the next season began, Henrietta and Marie joined forces and were advertised as the Irving sisters. While Henrietta’s career in the theater would last decades before her death in 1905, Marie’s foray only lasted a couple of seasons.

On January 21, 1861, John Wilkes Booth made his debut in Rochester, playing Romeo to Henrietta Irving’s Juliet. After the Shakespearean play was done, Marie Irving starred in the comedic afterpiece, the Rival Pages.

The engagement proceeded normally for two weeks, with Booth and the Irving sisters performing various plays together in different combinations while supported by the local theater company. Booth was very well received in Rochester, with the newspapers comparing him favorably to his revered father, Junius Brutus Booth. Booth’s time in Rochester ended on February 2, but his next engagement in Albany didn’t begin until February 11th. His whereabouts during this week are unknown, but he may have stayed in Rochester. It has been claimed that during this period in Rochester, Booth was engaged in a tryst with his leading Juliet, Henrietta Irving.

The details of Booth and Henrietta’s romance are difficult to know for certain. It is the stuff of gossip with conflicting sources. In the years after Lincoln’s assassination, columnist George Alfred Townsend (GATH) dug up as much dirt about Booth’s life and career as he could. In his 1865 book, The Life, Crime, and Capture of John Wilkes Booth, GATH described Booth and Henrietta’s relationship thusly:

“They assumed a relation creditable only in La Bohéme, and were as tender as love without esteem can ever be.”

Years later, GATH interviewed Matthew Canning, Booth’s agent during this tour. Canning stated that Booth’s “chief passion was for women.” We must remember that Booth was a rising star during this period. Womanizing and sex followed naturally from his growing success. During the same period in Edwin Booth’s life, the elder brother had also lived the Bohemian lifestyle of casual sex. In 1858, Edwin wrote a letter to his brother, June, bragging about bedding a supporting actress at the theater, saying, “can’t brag on her acting so much as what we do in secret.” The fact that Dr. Ernest Abel was able to write an entire 400+ page book about John Wilkes Booth and the Women Who Loved Him demonstrates that JWB was also not short on female companionship during his brief 26 years of life.

Without naming names, Canning recalled to GATH that Henrietta was “Booth’s temporary mistress” during their time in Rochester. Eventually, Booth had to leave for Albany. He performed at the Gayety Theatre in Albany from February 11 through March 16, with one week off during the run. After this engagement ended, JWB headed to Portland, Maine, just as Henrietta arrived in Albany for her own engagement at the Gayety Theatre. Even though Marie is not listed in the newspaper advertisements, she likely appeared alongside her sister in Albany.

John Wilkes Booth was in Portland from March 18 through April 13. During the first week, he performed alongside another pair of acting sisters, Lucille and Helen Western. Booth had acted alongside the pair a year earlier when he was still a lowly stock actor in Richmond, Virginia. The “Star Sisters,” as the Westerns were known, made ample use of their good looks. They often put on more exotic shows with costumes that showed off their figures or even saw them dressed as men. Some of their regular plays were filled with sexual innuendo, and they thrived on courting controversy. However, as successful as the “Star Sisters” had been, the duo was at the end of their time together. Their engagement with Booth marked the last time the Western sisters would appear on stage together. In his book, Dr. Abel writes that John Wilkes Booth likely made a “temporary mistress” out of seventeen-year-old Helen Western during their time in Portland together, but the evidence to support this claim is lacking.

After his time with the Western sisters in Portland was over, Booth returned to Albany for a repeat engagement at the Gayety Theatre starting on April 22. Henrietta Irving had just concluded her own run at the theater and had last appeared on April 19. Whether she performed supporting roles to Booth in April is unknown. The newspaper advertisements for this engagement only mention Booth sharing billing with “Signor Canito, the Man Monkey.” The “signor” was a New York actor by the name of Samuel Canty, who dressed as a monkey and performed in acrobatic plays he wrote himself.

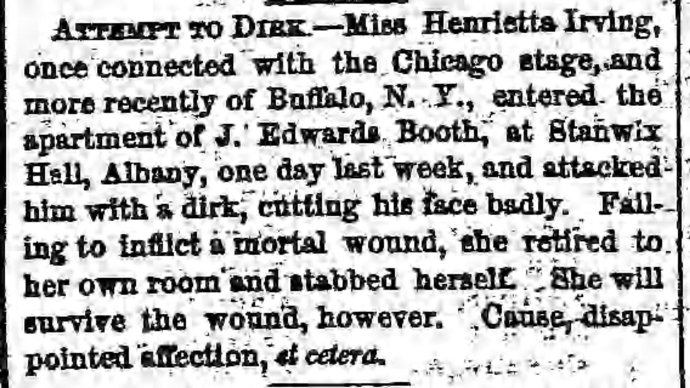

Booth’s engagement with the monkey man was going well until April 26, 1861, when Henrietta Irving made her attack. The details are unclear, but the incident occurred at the Stanwix Hall hotel in Albany, where both Booth and Irving were staying. Irving stabbed at Booth with a dagger, aiming at his face – the stock and trade of any handsome actor. Booth managed to parry the blow, but not before receiving a bloody gash on his cheek. Having failed in her attack, Irving returned to her own hotel room at the Stanwix and stabbed herself. The attempt at suicide proved non-fatal, and both the victim and the attacker survived their knife wounds.

The newspaper articles that popped up about the incident were vague. Most seemed to believe that Henrietta Irving’s attack on Booth was due to a love affair gone wrong. The short blurbs that popped up in papers about the incident blamed the stabbing on “disappointed affection,” “misunderstanding,” “jealousy,” “or some little affair of that sort.”

The miniseries suggests that the stabbing may have been due to Booth taking an interest in Henrietta’s sister, Marie, during this time. There is some evidence to support this. In the same 1886 interview between GATH and Matthew Canning, Booth’s former agent recalled:

“There were two sisters in the company [in Albany], and neither of them very considerate. One of them was Booth’s temporary mistress, and he got a fancy for the other one, and the first sister kept watch on him, and as he was coming out of the other one’s room she jumped on him and stabbed him.”

This recollection from Canning implies that Booth had shifted his desires from Henrietta to her sister Marie and that Henrietta attacked him as a result. Whether this attack was from jealousy on Henrietta’s part or an attempt to protect her sister from a lothario she knew all too well is uncertain.

The incident marked the end of Booth’s debut touring season. The wound was not severe, but the latest of several misfortunes that had befallen the novice star, and Booth was ready for a break. From Albany, he returned home to Maryland and spent ten weeks at the family home of Tudor Hall memorizing and practicing plays for his next season.

Henrietta Irving’s career was not hampered by the bad press. She continued to act and married fellow actor Edward Eddy in 1867. We’ll probably never know her true motivation for stabbing Booth and then turning the knife on herself in 1861. In an autobiography she wrote before her death in 1905, Henrietta Irving makes no mention of John Wilkes Booth.

- The Favorite

While in the barn talking with Davy before the authorities arrive, Booth goes into a monologue regarding his relationship with his mother and father. I’ll cover more of this in the sections that follow, but I did enjoy one part of it. During his monologue, Booth recounts that his mother “didn’t play favorites like my father.”

Despite Booth’s claim that Mary Ann Booth “didn’t play favorites,” it was well-known among the Booth children that she did and that Wilkes was the favorite. Granted, this had not always been the case. The original favorite had been Henry Bryon Booth, the fourth of the Booth children. He had been named after the famous poet Lord Byron, whose words helped Junius woo Mary Ann into leaving England with him. Henry Byron died of smallpox at the age of 11 in December of 1836, while the family was on an extended visit to England. The Booths were devastated by the loss of this boy, with Junius writing back to his father in America:

“We have at last cause and severe enough it is, to regret coming to England. I have delayed writing till time had somewhat softened the horror of the event. Our dear little Henry is dead! He caught the small pox and it proved fatal – he has been buried about three weeks since in the chapel ground close by. Guess what his loss has been to us – So proud as I was of him above all others.”

John Wilkes Booth was the first child born after the death of Henry Byron. When he came in May 1838, it helped put the light back into a still-mourning Booth household.

In addition to the timing of his birth, John Wilkes possessed a strong loyalty to his mother. He acted as the man of the house while his older brothers, June and Edwin, traveled west on their acting careers. After Junius, Sr. died in 1852, John Wilkes tried his best to work the family farm and provide for his mother and siblings. Eventually, a successful Edwin came home and saved the family from their poverty, but it had been Wilkes who had stuck by his mother’s side during these hard times.

The fact that Mary Ann favored Wilkes over her other children was not resented by the other siblings, either. In her own book about her brother, Asia wrote that she was closer to John than any of her siblings. When Mary Devlin Booth, Edwin Booth’s wife, died in 1863, John Wilkes canceled his engagements to rush to his grieving brother’s side. He regularly corresponded with his eldest brother, June, and took a great interest in the lives of his nieces and nephews. Wilkes even tried his best to provide some guidance and structure to his youngest sibling, Joe, whose lack of purpose and melancholy greatly worried their mother. As historians William Edwards and Edward Steers, Jr. concluded: “John was everyone’s favorite.”

With all this being said, I actually enjoy this part of Booth’s monologue in which he relates that his father played favorites, but his mother did not. Wilkes is either purposefully misrepresenting or completely ignorant of the fact that he is his mother’s favorite child. The former would demonstrate Booth’s manipulative nature and ability to lie to make himself look better, while the latter would show how selfish and narcissistic Booth was. The entire family knew and acknowledged that Wilkes was his mother’s favorite child, but his own self-pity and hurt ego over the idea that he wasn’t also his father’s favorite blinds him to the truth of his elevated status. I like this line as it is yet another example of something the miniseries accidentally gets right when you know the true context.

- His Mother’s Prophecy

In the same monologue mentioned above, Booth recalls being the victim of a cutting insult on the part of his father and that his mother then came to his aid. Mary Ann looked at the palms of Booth’s “beautiful hands” and predicted that one day, her son would do something important with those hands. To Booth, his shooting of Lincoln was the fulfillment of his mother’s words, and that prophecy, not the soothsayer’s prophecy from episode 3 predicting his early demise, gave him comfort now.

This little story of Mrs. Booth having a vision of her son’s future actually has some basis in fact, though it comes from well before Wilkes could speak. In Asia Booth’s book about her brother, she recalled a family story told to her by her mother. It revolved around a night, not long after the birth of John Wilkes, when the mother was trying to coax her newest child to sleep as they both sat in front of a fire. According to Mary Ann, while thinking about the future of her young boy, she witnessed a vision. The story of what she saw was repeated so often that, in 1854, Asia wrote the story as a poem and presented the piece as a present for her mother’s birthday. Asia’s poem of “The Mother’s Vision” is as follows:

THE MOTHER’S VISION

Written 1854, June 2nd, by A.B., Harford Co. Md.

‘Tween the passing night and the coming day

When all the house in slumber lay,

A patient mother sat low near the fire,

With that strength that even nature cannot tire,

Nursing her fretful babe to sleep –

Only the angels these records keep

Of mysterious Love!One little confiding hand lay spread

Like a white-oped lily, on that soft fair bed,

The mother’s bosom, drawing strength and contentment warm –

The fleecy head rests on her circling arm.

In her eager worship, her fearful care,

Riseth to heaven a wild, mute prayer

Of foreboding Love!Tiny, innocent white baby-hand,

What force, what power is at your command,

For evil, or good? Be slow or be sure,

Firm to resist, to pursue, to endure –

My God, let me see what this hand shall do

In the silent years we are tending to;

In my hungering Love,I implore to know on this ghostly night

Whether ’twill labour for wrong or right,

For – or against Thee?

The flame up-leapt

Like a wave of blood, an avenging arm crept

Into shape; and Country shone out in the flame,

Which fading resolved to her boy’s own name!

God had answered Love-

Impatient Love!

The story of Mary Ann Booth seeing the flames of a fire spell out “Country” and then John Wilkes Booth’s name is a compelling one that would have been perfectly suited for a dramatic recreation. While I wish that the miniseries had been more exact in recounting the details of this vision, I appreciate their hint at the family story.

- Explaining the Trial

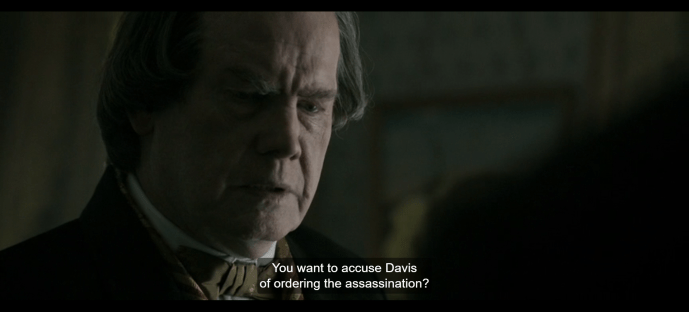

In the second half of this episode, we see Secretary Stanton preparing for the trial of the Lincoln conspirators. The series actually does a good job of showing Stanton’s strong belief that Jefferson Davis and other leaders of the Confederate government were behind the actions of John Wilkes Booth. We’ll talk more about this belief and how Stanton’s devotion to this theory ended up compromising the government’s case in the review for the final episode of the series.

However, I did appreciate how well the series showed a fictitious yet conceptually accurate discussion between Sec. Stanton, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, and President Johnson regarding the way in which the trial of the conspirators was to be conducted. The participants aptly explained the “danger” of attempting to try the conspirators in a civilian court where a jury of their peers might rule in their favor. JAG Holt explained how a panel of military judges would be better suited to the task and, of course, explicitly chosen by the War Department for the task. The scene also had Johnson lay out a basic but historically correct argument for why the conspirators should be tried by a military court for their assassination of the commander-in-chief. The whole scene was well written and explained a controversial decision using very human and understandable terms.

I also appreciate how Both Stanton and President Johnson were shown to be united in this area. One of my critiques has been how the series has shown the two to be at odds far too often this early in their relationship. Johnson wanted vengeance for Lincoln just as much as Stanton did. It was only as Johnson’s presidency went on that his deviations from his predecessor’s actions and beliefs caused an irreconcilable fissure between the men.

- Will Harrison as Davy Herold

Back in my review for episode 3, I recounted how much I was enjoying how the writers managed to make David Herold a complex figure and how impressed I was with Will Harrison’s performance of this often-overlooked conspirator. My admiration for both Harrison’s acting and the interpersonal writing of his character only increased with the stand-out performance in the penultimate episode of the series. Herold experiences a whole gamut of emotions in this episode. In the barn, he finally refuses to entertain Booth’s ego and delusion any longer, and he is the only one of the two who truly acknowledges the severity of their circumstances. Herold is then noticeably wounded when Booth turns on him and projects his own inadequacies onto the pharmacist’s clerk, who had been nothing but loyal to the assassin up to now. Even though Booth is not worthy of his devotion, he still begs the assassin to live and not give up his life unnecessarily. Then, from his lonely prison cell, Davy acknowledges the powerful influence Booth had on him, yet is still unable to completely free himself from it, begging to read Booth’s diary once more.

Both Herold and Sec. Stanton reflect on their friends Booth and Lincoln, and how they made each feel important. Yet Herold fails to realize that his relationship was one-directional and with a narcissist who could only take. Though Tobias Menzies’ Sec. Stanton was correct that David Herold can’t be forgiven for what he did, Will Harrison’s portrayal of the conspirator in this episode returns a much-needed humanity to this historical figure.

- An Equivocal Code

I was pleasantly surprised by part of the scene in the War Department where both JAG Holt and Thomas Eckert expressed their concerns to Stanton about the strength of the evidence to support the idea of a grand conspiracy involving the Confederate government. Stanton manages to acknowledge these shortcomings but is still unwilling to change his mind. He relates how the other side has shown its willingness to bend the rules and suggests his team do the same (as if trying the conspirators in front of a military court wasn’t bending the rules enough already).

As part of their equivocal evidence connecting Booth to Jefferson Davis is a coded message from Davis to John Surratt stating, “Come Retribution,” and the discovery of a cipher table in Booth’s room. As Holt and Eckert note, they can’t prove that the coded message related to the assassination or that Booth ever even saw it. To this, Stanton responds, “Very few, if any, understand how code works,” before ordering Eckert to “make it sound more definitive than it is.”

While I was not a fan of the miniseries creating a fictional coded message from Jefferson Davis to John Surratt just for the sake of intrigue, I am very happy that they are explicitly showing that the existence of Booth’s cipher table has been greatly misconstrued as being evidence of a connection between Booth and the Confederacy. I wrote as much in a blog post here back in 2019 entitled Booth’s “Confederate” Cipher (which you should all read). Given how very few others have ever written about Booth’s cipher table, I’d like to think one of the writers of this series read my post. In summary, the cipher table found in Booth’s room is in no way evidence of connection to the Confederate secret service. If you want to learn more, read the post.

Let’s dig now into the fact vs. fiction of this episode and learn about the true history surrounding these fictional scenes.

1. Booth’s Other Wound

In addition to mentioning the stab wound he received from Henrietta Irving, Booth shows Davy another wound he survived in the past. He points to a scar on his right hip and tells Davy that it was caused by a crazed fan who shot him in Columbus, Georgia. Booth then goes on to state that if Davy were to visit Columbus, he might hear some gossip of, “Booth’s own pistol going off in his pocket.” But Booth denies this story and assures Davy it was a deranged fan who shot him “demanding an autograph while I was taking home an ingenue.”

I appreciated how the miniseries clearly shows that Booth is making up a story to protect his vanity. However, even the “true” story that we are supposed to infer from this exchange – that Booth accidentally shot himself with a gun – is not exactly accurate.

The event in question happened on October 12, 1860, during Booth’s ill-fated debut season that would end with him being stabbed by Henrietta Irving. A concise version of what occurred can be read in this newspaper article.

I’ve written at length about Matthew Canning accidentally shooting his lead actor in a 2012 blog post entitled “Shooting Booth,” which I encourage you to read if you want to know the full story. While Booth may have had a hand in his own shooting, it would not be accurate to say that his own pistol went off in his pocket.

2. “Boy, you are useless.”

In the part of Booth’s barn monologue where he talks about his relationship with his parents, he recounts a time when he approached his father and asked the elder tragedian to train him as an actor. According to Booth, Junius responded cuttingly with, “Boy, you are useless,” dashing his hopes.

In this way, the miniseries is once again returning to the idea that Booth’s choice to assassinate Lincoln was motivated by an intense inferiority complex. While I have no doubt that the Booth family dynamic had an impact on John Wilkes Booth, I still find the belief that Booth did what he did because his father and brother were better actors than he was to be too contrived and simplistic.

I would agree that Booth likely felt that his father played favorites and that his brother Edwin had been given chances he had not. Part of this, however, was due to the age difference between Edwin and Wilkes. Their father’s alcoholism increased greatly in his later years, deeply impacting the family’s income stream. In earlier years, Mary Ann traveled with Junius to keep him sober, but her household was far too big for this to continue. She assigned her eldest boy, June, to the role of his father’s guardian for a time, but soon, June had a family and life of his own. In 1848, Junius needed a new traveling companion. The options were limited. While daughter Rosalie was 25 years old, it would not have been deemed appropriate for a daughter to become her father’s keeper. The only remaining Booth boys were Edwin, Wilkes, and Joe. Of these, Edwin was the oldest at 14, followed by Wilkes, who was 10. By necessity and by age, Edwin became his father’s assistant. Wilkes was no doubt jealous of the opportunity and theatrical education his brother received in watching their father perform in cities across the nation. However, he was also ignorant of the immense struggles Edwin endured trying to keep their father out of the bottle and on the stage night after night. For both brothers, the grass was greener on the other side. While Wilkes was jealous that Edwin got to travel with their father, Edwin lamented his lost childhood and his lack of a formal education.

There is no evidence that Junius ever called Booth “useless.” The idea that Junius did not want to train Wilkes as an actor might be true, but likely not because of the old man playing favorites. In reality, Junius attempted to dissuade all of his sons from pursuing acting as a vocation. Junius knew firsthand the difficult lives actors lived. They were constantly away from their homes and families, and even the most successful of actors often struggled to make ends meet. Junius desperately desired for his children to go into respectable careers with stability. Actors were celebrated for their histrionic talents, but the applause was fleeting. It wouldn’t be until Edwin Booth established The Players Club in his later years that actors were welcomed as equals amongst men of power and influence.

In truth, had Junius been able to control his drinking and manic bouts, he may have been successful in preventing his sons from becoming actors. Without a need for a guardian, his two sons, June and Edwin, could have continued their studies and found other careers. Instead, they had to accompany their father, and their education and job training became that of the theater to which Junius was bound. While John Wilkes Booth was never tasked with being his father’s keeper in this way, his rose-colored interpretation of his brothers’s experiences led him to also want to be an actor.

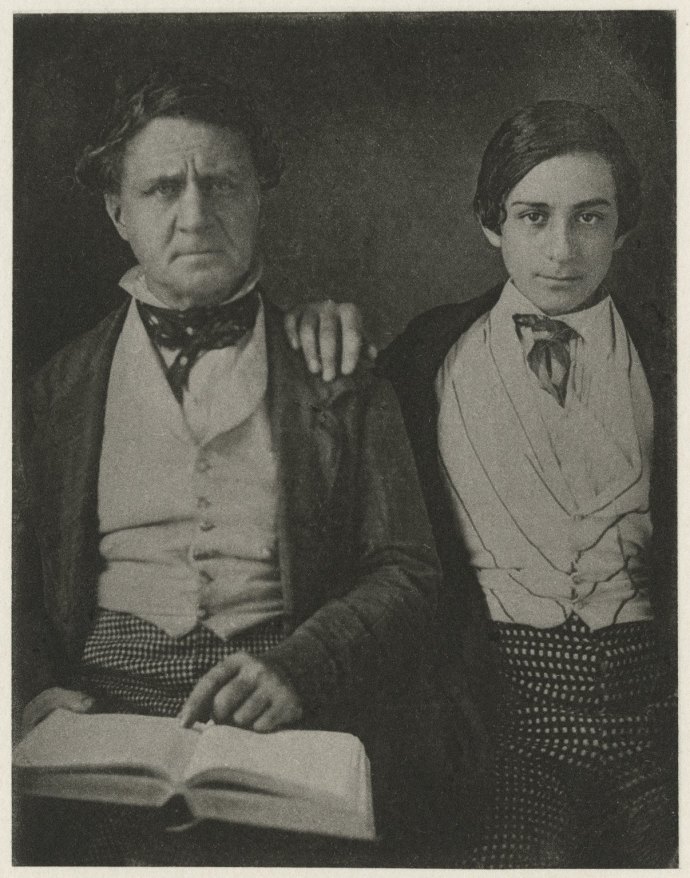

3. The Garrett Family

One of my particular interests in the Lincoln assassination story is John Wilkes Booth’s time at the Garrett farm right before his death. He interacted quite a bit with the Garrett family, who were ignorant of his identity and agreed to take him in under the belief that he was merely a wounded Confederate soldier in need of assistance. The assassin spent about 39 hours at the Garrett farm before meeting his demise. He spent the first of his two nights sleeping comfortably in a bed inside the Garrett home as the family did not yet have any reason to suspect their houseguest was anyone other than what he claimed to be. It was only after the re-arrival of Davy Herold on the second day and the two men’s subsequent reaction to members of the 16th NY Cavalry riding by the farm that gave the family pause and resulted in the men’s banishment to the tobacco barn for Booth’s second night. Practically all documentaries and dramatic series fail to accurately portray this timeline. They all make it appear as if Booth showed up at the Garrett farm and was almost immediately condemned to the barn, where the troops cornered him a few hours later.

In truth, I had high hopes for Manhunt to finally show an accurate representation of the Garrett farm, Booth’s interaction with the family, and his death. Unfortunately, most of what is shown in this episode regarding the events at the Garrett farm is fictitious and only loosely based on fact.

The episode opens with Julia Garrett, fresh off of her awkward “bathing Booth” duty from the prior show, telling the men that they can’t stay overnight as her daddy will question her honor if they are found in the house. After some wooing by Booth, Julia agrees to let Booth and Herold take their horses in the morning, but only if her daddy approves. Julia leads them to the barn, and Booth once again tries to work his awkward magic on her, but she rebuffs him and locks the men in the barn, leading to the barn discussions between Booth and Herold that were previously mentioned.

Apparently, Julia’s daddy never comes home, as she remains the only member of the Garrett household that we ever see. While one of the children born to Richard Henry Garrett was named Julia, the real Julia Frances Garrett died in 1851 when she was less than a year old. The miniseries never shows the many other Garrett family members who interacted with Booth during his time at the farm, nor does it cover the actual series of events that led to Booth and Herold being locked into the barn and guarded by Jack and Will Garrett. The Garrett family did not know the true identity of the man they had been entertaining until he was already shot and dying on their porch. Booth was locked into the barn because he and Herold told the Garretts that they had gotten into a scrape with the Union cavalry over some horses, and so the Garretts were fearful the men might be horse thieves. They were locked into the barn to protect the Garrett horses, not because the Garretts suspected they were involved in the assassination of Lincoln.

4. The Fire Is Started Too Quickly

As is common in these types of dramatic portrayals, the miniseries shows the troopers lighting the tobacco barn on fire seemingly within minutes of their arrival at the Garrett farm. In reality, quite a lot of time took place between the arrival of the 16th NY Cavalry and the act of actually setting the tobacco barn housing the fugitives on fire. The act of dismounting the horses in groups of two and situating the horses away from where the blaze was planned took over a half hour as the cavalry was careful to maintain an unbroken line around the tobacco barn. Even after the dry brush was placed next to the barn in preparation to smoke them out, another hour went by as the soldiers tried to convince Booth to give himself up. The whole affair was a relatively patient one, as the soldiers wanted to capture Booth alive and were not out to destroy the Garrett property if it could be avoided. In the end, though, the trooper’s patience wore thin, and Luther Baker told the men that the barn would be set on fire in five minutes if they did not surrender themselves.

It was after this final ultimatum, given over an hour and a half after the arrival of the troopers, that David Herold finally surrendered himself. He did so before the barn was set on fire, and he came out alone with Booth verbally downplaying Herold’s involvement to the troopers as a way to protect his trusted conspirator. It was only after Herold’s surrender and his being secured to a nearby tree that Everton Conger lit the barn on fire, and Booth was shot within a matter of a minute or two.

5. The Shooting and Death of Booth

In the miniseries, David Herold is sent back into the burning barn in order to convince Booth to live another day by giving himself up. After telling Booth that his only chance is a day in court, Booth rises and begins to walk out of the burning structure with Davy leading the way. At this moment, Corbett finds a hole in the side of the barn, aims his pistol through it, and fires. The bullet strikes Booth, causing him to collapse. From Davy’s entreaties for help, the soldiers pull him from the barn, and Corbett appears to take credit for his actions, noting “what a fearsome God we serve” when told he struck Booth in the back of the head, “just like Lincoln.” The delirious and partially paralyzed Booth asks about Jefferson Davis before being placed on the porch of the Garrett house. Julia Garrett places a pillow behind Booth’s head and says he needs a hospital, but a soldier notes that he won’t survive the hour. In reality, the assassin doesn’t survive the minute as he chokes and spits up blood while calling for Davy. Booth then turns to Julia, mistaking her for his mother, and tells her, “Don’t look at my hands.” After a few more gasps, Booth mutters, “Useless, Useless,” and dies.

From a global view, this portrayal of the shooting and death of Booth is fine. They have most of the highlights from the story: Booth is shot by Boston Corbett as he heads towards the barn door, the mortally wounded assassin is placed on the Garrett house porch, and Booth says, “Useless, useless” before he dies. All of these things happened, but not so quickly, and, of course, many other things also happened.

John Wilkes Booth was shot at around 4:00 am on April 26th and died a bit before 7:00 am. During the last three hours of his life, he regularly floated in and out of consciousness. While lying on the porch of the house, a mattress was placed under him, and the soldiers and Garrett family members took care of him as best they could. On more than one occasion, Booth asked the soldiers to kill him, but they refused, saying it was their hope he would recover. The detectives emptied Booth’s pockets and took stock of his valuables. A doctor was sent for and arrived from Port Royal to examine Booth and announced his wound as mortal. After making his prognosis, the doctor departed. Talking was difficult for the assassin as the bullet had passed through the back of his neck. Booth’s final conscious act was to ask the soldiers to raise his hands in front of his face so that he could see them. It was to his hands that he directed his final words of “Useless, useless.” After this exchange, he fell back into unconsciousness and died not long after.

6. The Disposition of Booth’s Body

At the Garrett farm, Edwin Stanton entrusts his son Eddie with the disposal of John Wilkes Booth’s body. He orders that a coroner fully document the body first and for Eddie to then dump it into a body of water. The Secretary states he doesn’t even want to know where the body is dumped. He insists that there should be no place where people could go to honor the assassin and tells Eddie to also dispose of decoy corpses in case he is followed. While mention is later made that an autopsy has been performed, we never see this on camera. However, we do witness Eddie following his father’s disposal instructions at the very end of the episode as he and Luther Baker dump a body in a river and then bury two others in random locations.

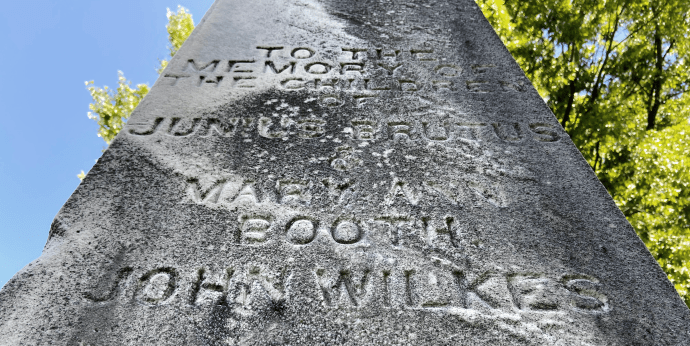

In reality, Booth’s body was never condemned to a watery grave. After an autopsy was performed, his body was placed in a boat and rowed to the grounds of the Old Arsenal Penitentiary, the same place where the conspirators would shortly be imprisoned and tried. Booth’s remains were buried under the floor of a storeroom. Edwin Stanton, himself, kept the key to this storeroom. In 1867, that part of the old building was slated to be demolished, so Stanton sent the key and men over to move Booth’s remains. Booth was buried in a different warehouse on the grounds, in a common grave in which David Herold, Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, and George Atzerodt were also reburied. During the final days of Andrew Johnson’s presidency in 1869, the lame-duck president authorized the removal of the bodies and turned Booth over to his family. They transported him to Baltimore and buried him in the family plot at Green Mount Cemetery. While John Wilkes Booth does not have his own headstone in the plot, his name does appear on the back of the Booth obelisk, noting him as a child of Junius Brutus and Mary Ann Booth.

To be fair to the miniseries, there was a lot of misinformation out there about the final disposition of John Wilkes Booth. So many rumors swirled that Booth really was sunk into the Potomac that Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper devoted the cover of their May 20, 1865 edition to a supposedly “authentic sketch” of the deed. In the decades that followed, more than one former sailor/soldier claimed to newspapers that he was the last remaining member of the “sinking detail.” However, the actual whereabouts of Booth’s corpse have been well documented, and we can rest assured that he lies in Green Mount Cemetery, not at the bottom of the Anacostia or Potomac Rivers.

7. A Reluctant Baptist Washington

There is a brief scene in which Dr. Mudd is shown conversing with a group of his neighbors and his brother-in-law, Jeremiah Dyer, asking which of them would be willing to testify on his behalf at his trial. Dr. Mudd correctly recounts that he is not permitted to testify on his own and that he needs them to swear to his good character.

After making his appeal, each of the gathered crowd raised their hand in support of the doctor, save one. This lone holdout is Baptist Washington, the only Black man present among his white neighbors. Wordlessly, Dr. Mudd signals to Jeremiah, and the doctor’s brother-in-law slips Washington a collection of dollar bills. After pocketing the bribe, Washington raises his hand in support like the rest.

Baptist Washington was an actual person who testified at the trial of the Lincoln conspirators. Washington had been enslaved by Jeremiah Dyer before emancipation came to Maryland in November of 1864. While he was still enslaved to the Dyer family, Washington had been hired out to Dr. Mudd and worked at the Mudd farm during carpentry work between January and August of 1864. Washington was one of the few African Americans who testified on behalf of Dr. Mudd, mainly to counter the claims of the real Mary Simms, who stated that Dr. Mudd had harbored Confederate agents like John Surratt at the farm. There is no evidence that Baptist Washington was paid for his testimony.

However, as I wrote in my piece recounting the Formerly Enslaved Voices in the Lincoln Assassination Trial, there were reasons other than monetary why people like Baptist Washington may have felt pressured to testify in favor of an enslaver like Dr. Mudd. While many Black residents left the regions where they had been enslaved when emancipation came, many others did not have that option. Even when freedom came, people like Baptist Washington, his wife, and his children remained living among the people who had once enslaved them. Washington faced difficult choices in 1865 and beyond. Even if he didn’t want to testify on Dr. Mudd’s behalf, failing to abide by the wishes of his white neighbors in Charles County would have had lifelong negative repercussions for him. Many other formerly enslaved people who didn’t move away after freedom likewise chose appeasement rather than conflict. This appeasement became misconstrued by white authors as the “loyal slave” and “good master” narratives, contributing to the myth of the Lost Cause. But Dr. Mudd was far from the oxymoronic good enslaver, as evidenced by Elzee Eglent, who testified about Dr. Mudd shooting him in the leg for not working hard enough. It’s not surprising then that Baptist Washington and many others spent their whole lives appeasing the white folks around them and telling them what they wanted to hear. During Reconstruction and beyond, such appeasement was sometimes the only way to survive.

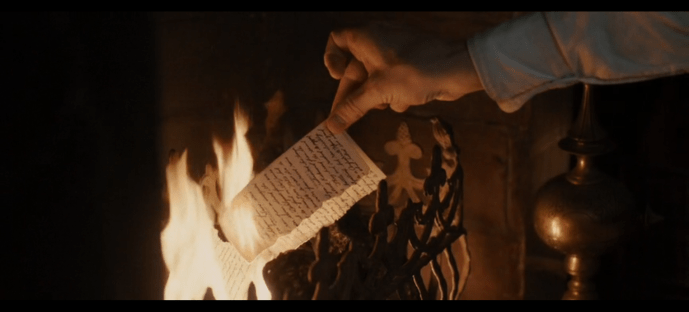

8. Burning the Diary Pages

Near the end of the episode, we see Edwin Stanton reading through the pages of Booth’s diary, which was recovered from his body at the Garrett farm. Eddie Stanton sees his father reading it and asks him, “Did Booth write down his motives?” followed by, “Is there anything in there that could stain your reputation?” The elder Stanton tells his son not to worry about it, and Eddie leaves. We then watch as Sec. Stanton approaches the room’s fireplace, kneels down in front of the flames, rips pages from the diary, and burns them to ash.

This scene was actually previewed in one of the teaser trailers for the series, so I knew it would come eventually. Still, it was my fervent hope that this series would not indulge this completely unsupported conspiracy theory that Stanton altered John Wilkes Booth’s diary. It is a truly baffling choice on the part of the writers of the series to include this completely fictional scene, especially since it has been their goal to show Edwin Stanton in a noble and heroic light.

The idea of Stanton destroying pages of Booth’s diary is based on the writing of chemist-turned-author Otto Eisenschiml. In 1937, Eisenschiml wrote his most famous work, Why Was Lincoln Murdered?, in which he claimed that Edwin Stanton was the chief architect of Lincoln’s assassination. According to Eisenschiml, Stanton worried that Lincoln was going to be too lenient with Confederate leaders after the war was over, so he had his boss killed as a result. Much of the “evidence” Eisenschmil provides to support his thesis is blatantly false or highly circumstantial. Still, the controversy over his claim grabbed the attention of the public, and there are still those today who falsely believe that Stanton had a hand in Lincoln’s murder and that he destroyed the pages of Booth’s diary that incriminated him.

In reality, there is no evidence that Booth’s diary was altered after it was recovered from him. Booth’s diary, as we know it, is actually a pocket date book for 1864. The pages that have been removed from the book correspond with the pages for January 1 – June 10, 1864. It is important to remember that, during the first half of 1864, John Wilkes Booth was still a working actor, traveling from city to city performing on stage. This book was likely used by the actor to keep track of his engagements, travel expenses, his percentage of the box office, and other assorted personal affairs. This diary was never intended to be his last manifesto. Booth had written his true motivations and given the papers in a sealed envelope to his friend John Mathews with instructions to turn the papers over to the newspapers the next day. After Mathews witnessed his friend assassinate the President, the Ford’s Theatre actor read the manifesto and then burned it out of fear it would incriminate him in Booth’s plot. While on the run, Booth was distraught to find that his words had not been published in the papers. He attempted again to make his thoughts known and was forced to make do with this otherwise forgotten 1864 datebook, which he still had tucked in his coat pocket. The most likely and logical reason for the missing pages in Booth’s diary is that the assassin ripped them out himself in order to remove the mundane details of a traveling actor in 1864 and ensure a clean slate for his last manifesto.

If you’re interested in reading the text of John Wilkes Booth’s diary, I transcribed it in a post here.

No reliable evidence supports the idea that Edwin Stanton, or anyone other than John Wilkes Booth, altered his 1864 datebook. This miniseries does a great disservice to history by portraying this completely fictitious scene, which only succeeds in spreading a long-debunked and baseless conspiracy theory to the masses. I’m still shocked that this otherwise pro-Edwin Stanton miniseries embraced the ugliest of conspiracy theories against him. I’m no Edwin Stanton fan, but he deserved better than this.

Quick(ish) Thoughts

- While I really liked the opening dream sequence, the shots of Booth’s horse grazing in the woods reminded me that there was never any follow-up to Davy’s horse galloping away from the pair in episode 3. You’ll remember that Booth shot his horse in the pine thicket and ordered Davy to do the same to his. But Herold was unable to kill the animal, and it ran off. At the time, I was convinced that the horse would be found in a later episode. But this never came to be, likely because the following episode had nothing to do with the actual manhunt and dealt with the fictional George Sanders intrigue. I supposed it’s all for the best anyway since, in reality, both horses were shot and sunk in the Zekiah Swamp by Davy Herold and Franklin Robey.

- When Booth shows Davy the scar from his 1860 Columbus gunshot wound in his right hip, Davy suggests that this wound was why Booth’s “leg broke on that side” when jumping from the box at Ford’s Theatre because the “bones were still fragile.” We’ve already discussed that the real Booth broke his left leg, not the right, as the miniseries portrays. But even overlooking this fact, a bullet in the hip would not make the bone in your lower leg just above the ankle “fragile.” I know Davy was not a doctor, just a pharmacy clerk, but this claim makes no sense. Even the miniseries Booth seems to think this suggestion is nonsense, dismissing Davy’s idea with a “yeah, possibly.”

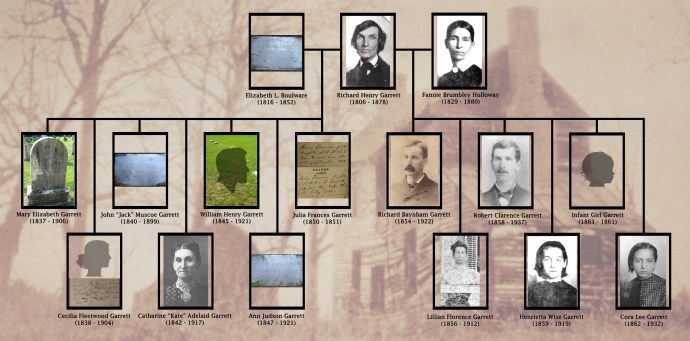

- Booth recounts to Davy that his “mother had many children. Four passed away. Three to cholera. One fell swoop.” It’s true that out of the ten children born to Mary Ann and Junius Brutus Booth, four died before reaching adulthood. They were Henry Bryon, Mary Ann, Frederick, and Elizabeth. But it was only two children who died of cholera at the Booth family farm in “one fell swoop.” These were Mary Ann and Elizabeth, who both died within days of each other in 1833 at about the ages of 5 and 2, respectively. Both sisters had been predeceased by their brother Frederick, who died in Boston in 1828 at the age of 16 months. In December of 1836, eleven-year-old Henry Byron Booth died of smallpox while the family was visiting England. With the exception of Henry Bryron, who was buried in England, the other three Booth siblings were buried at the family farm of Tudor Hall. In 1869, after the government agreed to release John Wilkes Booth’s body to his family, Mrs. Booth had the remains of her three young children disinterred and moved to Green Mount Cemetery, where Edwin had purchased a large plot. The remains of Frederick, Mary Ann, and Elizabeth were placed in a single coffin and buried on top of their younger brother, John Wilkes, in the family plot.

- While I still enjoyed the portrayal of William Mark McCullough as Boston Corbett in this episode, I feel that the writers made him a bit too zealous in this, his big climatic episode. Corbett, the lowly sergeant, single-handedly leads the cavalry, busts down the Garrett House door, pulls a pistol on and then chokes Julia Garrett, and later offers to go on a suicide mission into the barn to draw Booth’s fire until the assassin is out of ammo. Corbett certainly was a zealous and eccentric man, but he did not have a death wish. Nor would he have overstepped his role as a sergeant. The miniseries never shows Captain Edward Doherty, the leader of this detachment of cavalrymen, but even without him, Everton Conger and Luther Baker were in charge. Corbett is just a bit too crazy in this episode.

- After the barn is set on fire, Julia Garrett rushes towards it and tells the soldiers they have to get Booth out of there. Again, the Garretts never knew that Booth had been their guest until after he was shot. After this comment, Corbett tells Julia, “This is a federal investigation. You’re obstructing.” These words sound painfully modern and out of place in this historical context.

- As quickly as the troopers in Manhunt are to set fire to the tobacco barn, the structure itself burns at an amazingly slow pace, and the fire never seems to catch on anything inside the barn. For a barn that was filled with dried tobacco leaves and hay, this is beyond belief. But I suppose an asbestos-lined barn was necessary so that the news of the barn being lit could reach Stanton back in Bowling Green and for him to think he could make it to the Garrett farm before it was over.

- When looking over the corpse of John Wilkes Booth at the Garrett farm, Edwin Stanton touches Booth’s hair as he states, “You’re no one now.” This is reminiscent of the many locks of hair that were cut from the assassin’s head. While lying on the Garrett porch, one of the Garretts cut a lock of Booth’s hair, and part of that lock was later sent to Mary Ann Booth. When Booth’s body lay on board the USS Montauk during his autopsy, locks of hair were snipped by visitors who identified him. Just before his final burial in Green Mount Cemetery in 1869, more hair was cut from his head as a keepsake for his family. Keeping locks of hair of the deceased was a very common Victorian mourning custom.

- Oswell Swann is partially redeemed in this episode. After Booth’s death, there is a scene in Bryantown between Swann and Luther Baker. Swann tells Baker that Booth and Herold had passed that way, with Baker replying, “Yeah, we got your tip,” implying that Swann had alerted the authorities at some point. However, Baker next complains that this tip did not come earlier, leading Swann to defend himself and the dangers posed to him living in an anti-Lincoln community. While this sentiment is fair enough, I still don’t feel this redemption is enough to undo the damage done to the real Swann in prior episodes in portraying him as an active agent for the Confederate underground.

- After this episode features the capture of Jefferson Davis, there is a scene between Eckert and Stanton in the War Department where Stanton orders that the press be told Jefferson Davis was captured while wearing his wife’s dress rather than just her shawl. According to Stanton, the reason for this is because, “they humiliated Abe when he wore women’s clothes to avoid death threats in Baltimore.” It’s a bit unclear who the “they” are in Stanton’s sentence. It could be a reference to Confederate plotters like Davis or perhaps even the press itself. Regardless, the point is moot, as Abraham Lincoln never dressed in women’s clothing, nor was he said to have dressed in women’s clothing to avoid assassination. The event references an event in 1861 to possibly assassinate President-elect Lincoln as he made his way by train to Washington for the first time. There were threats that an attempt might be made on Lincoln’s life in Baltimore, so he changed his plans at the last minute and essentially snuck through Baltimore ahead of schedule and arrived safely in D.C. After this was learned, Lincoln’s political enemies ridiculed him for cowardice. One reporter basely claimed that Lincoln moved through Baltimore wearing a scotch cap and a long cloak. While Lincoln was never disguised in such a way, this lie stuck, and many political cartoons were made of the new President slinking into or panic-strickenly dashing into Washington. The event did damage Lincoln’s ego a bit and may have contributed to his later distaste for guards and security.

I apologize for the six-month delay between my review of episode 5 and this one. In truth, my frustration with the series really zapped my motivation to continue with these in-depth reviews. Since Booth’s time at the Garrett farm and subsequent death is my favorite aspect of the story, seeing how much the miniseries botched this aspect really made the prospect of writing this review seem like an unwanted chore. However, I made a commitment to review all seven episodes of the series, and that is what I am going to do, even if I have to take lengthy breaks between each one. I will do my best to write my review of the final episode before another six months go by. I would really like to cross this project off my to-do list. Thanks for sticking with me.

Dave

Recent Comments