Friday, May 26, 1865

Previous Session Trial Home Next Session

- Proceedings

- Bennett Gwynn

- Father Peter Lanahan

- Father Nicholas Young

- George Calvert

- William Hoyle

- Philip Maulsby

- Philip Maulsby (cont.)

- Lewis Chamberlayne

- Henry Finnegass

- Charles Dawson

- Charles Sweeney

- James Young

- John Young

- John Nothey

- Dr. John Thomas

- Samuel McAllister

- Jeremiah Mudd

- Francis Lucas

- John Thompson

- Recollections

- Newspaper Descriptions

- Visitors

- References

Proceedings

The court convened at 10 o’clock.[1]

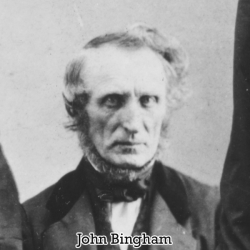

Present: All nine members of the military commission, the eight conspirators, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, Assistant Judge Advocates Bingham and Burnett, the recorders of the court, lawyers Frederick Aiken, John Clampitt, Walter Cox, William Doster, Thomas Ewing, and Frederick Stone.

Absent: Reverdy Johnson

Seating chart:

The prisoners were seated in the same manner as the day before.

The reading of the prior day’s proceedings was completed by court reporter James J. Murphy.

Frederick Aiken, lawyer for Mrs. Surratt, requested that the court recall Henry von Steinaecker, the very first witness who took the stand in the trial. Aiken wished to cross-examine von Steinaecker in order to discredit his testimony regarding having seen John Wilkes Booth in Virginia in 1863. Assistant Judge Advocate Bingham replied that Aiken had not presented a summons for von Steinaecker and that he had already been discharged as a witness. Bingham added that if Aiken made an official application for von Steinaecker then every effort would be made to secure him.[2]

Aiken’s request to recall von Steinaecker may have stemmed from a conversation with Henry Kyd Douglas, the Confederate soldier who had been held in one of the rooms adjoining the courtroom since May 24th. Douglas had been brought to Washington due to von Steinaecker’s testimony that the assassination was discussed within the lines of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson’s division of which Douglas was a part. In his later memoirs, Douglas wrote that, “As soon as I arrived I asked General Hartranft to have von Steinacker apprehended that he might face us, and sent the same request to General Hancock by Captain Ike Parker of his staff.”[3] Since Douglas had expressed to Hartranft and Lafayette Baker of the National Detective Police that he would refute von Steinaecker’s testimony, he was not called to testify for the prosecution and they did not make any efforts to recall von Steinaecker at that time. Douglas’ residency at the trial room makes it seem likely that he talked with Frederick Aiken and informed him of his desire to counter von Steinaecker’s claims, thus leading to Aiken’s request today. Aiken would later call Henry Kyd Douglas to the stand on May 30th.

Assistant Judge Advocate Henry Burnett produced two letters in the possession of the government that had been requested by the defense. The letters concerned the debts that brought Mary Surratt to her Maryland tavern on April 12 and 14. Both letters would be entered into evidence over the course of the day.[4]

Testimony began

Bennett F. Gwynn, a land agent and resident of Prince George’s County, was recalled he having previously testified the day before. Gwynn repeated that, on the afternoon of April 14th, he encountered Mrs. Surratt near her tavern and was given a letter. Gwynn took the letter and delivered it to John Nothey at the request of Mrs. Surratt. The letter having been furnished by the government was then read into the record. It concerned Mrs. Surratt requesting Nothey pay the debt owed her so that she can repay her own debt to George Calvert.[5]

The letter from Mrs. Surratt to John Nothey written on April 14, 1865, was entered into evidence as Exhibit 67.

Father Peter B. Lanahan, the rector of St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Charles County, Maryland, testified that he had known Mary Surratt for the past 13 years. Father Lanahan stated that he believed Mary Surratt had the reputation of a, “very good Christian woman” and that she had never expressed any disloyal sentiments that he had heard.[6] St. Peter’s Church, Father Lanahan’s parish, was the home church of Dr. Samuel Mudd yet Lanahan was never asked about Mudd or his reputation.

Father Nicholas D. Young, the pastor of St. Dominic’s Catholic Church in D.C., testified about having known Mary Surratt for about ten years but not all that intimately. Father Young stated that his understanding of Mrs. Surratt’s reputation was one of a Christian lady. He never spoke with her about the War and did not know her sentiments. He also had no knowledge of her eyesight.[7]

George H. Calvert, Jr., a wealthy landowner living near Bladensburg, Maryland, was recalled, he having previously testified the day before. He was asked to identify the letter he wrote to Mary Surratt on April 12th in which he asked her to settle the debt she owed to him. The letter was identified and read on to the record.

The April 12th letter from George Calvert to Mary Surratt was entered into evidence as Exhibit 68.

William L. Hoyle, a store clerk living in D.C., testified that he had a slight acquaintance with Mrs. Surratt and John Surratt from their visits to his store. Hoyle stated that he had never heard Mrs. Surratt utter any disloyal statements but also admitted that he was, “not particularly” aware of her general character. Hoyle was briefly asked to describe John Surratt’s appearance stating that he had not seen him since around early March.[8] Frederick Aiken’s purpose for calling Hoyle, a relative stranger, as a character witness for Mary Surratt is unknown.

Philip H. Maulsby, the brother-in-law of Michael O’Laughlen, testified about O’Laughlen’s whereabouts for much of 1864 and 1865. Maulsby testified that around 1862 Michael began assisting his brother, Samuel Williams O’Laughen, with his produce and feed business in Washington. Samuel Williams made his D.C. office a branch business and relocated himself to Baltimore. Michael acted on and off as his agent in the D.C. branch. Maulsby identified a telegram Michael received from his brother dated March 14, 1865, in which Michael was tasked with keeping tabs on some hay that had been shipped down to Washington. Maulsby also testified that Michael was back living at his place in Baltimore by around the 18th of March and stayed in the city until he went to visit D.C. with his friends on April 13th. Walter Cox, Michael O’Laughlen’s lawyer, then tried to ask Maulsby about the arrest of O’Laughlen. The arrest had been formerly testified to by a witness for the prosecution, William Wallace. That testimony showed that O’Laughlen was not arrested at his own home but at the home of another, creating the implication that O’Laughlen was avoiding arrest. Cox desired Maulsby to testify about how, after his return from D.C., Michael O’Laughlen agreed to surrender himself to authorities and told Maulsby to make the arrangements. While Maulsby eventually managed to get most of his testimony regarding this series of events out, he was constantly interrupted by the objections of Assistant Judge Advocate John Bingham.[9] The laborious and time consuming nature of Bingham’s objections were noted by several who attended the trial.

The telegram sent by Samuel Williams O’Laughlen to his brother Michael on March 14, 1865 was entered into evidence as Exhibit 69.

Break

In the midst of Philip Maulsby’s testimony, the court decided to take its normal one hour recess for lunch. During this time all of the conspirators were returned to their cells with the exception of Michael O’Laughlen who, according to the newspapers, “was allowed to hold a short interview with his brother-in-law, Mr. Maulsby.”[10] At 2 o’clock, the court reassembled and Maulsby’s testimony was resumed.[11]

Testimony resumed

Philip H. Maulsby, Michael O’Laughlen’s brother-in-law, continued his testimony. Through the continued objections of Assistant Judge Advocate John Bingham, Maulsby managed to narrate the arrest of Michael O’Laughlen, which showed that the conspirator peacefully surrendered himself. Lawyer Walter Cox then asked Maulsby his impression of John Wilkes Booth. This, too, was objected to by Bingham. Cox explained that the defense counsels desired some evidence regarding Booth’s character and power over people. Cox stated that he desired to explore Booth’s influence over others as a mitigating factor in his client’s supposed guilt. Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt replied that the crime of assassination cannot be mitigated by a man of “fascinating address and pleasing manners.” Cox agreed but asserted that Booth’s address and manners can be used to mitigate the actions of those acting under his influence. Holt merely replied, “Not at all,” and the court sustained Bingham’s objection, leaving the question about Booth’s influence unanswered.[12]

Lewis W. Chamberlayne, a former clerk in the Confederate War Department, was called as a prosecution witness. He testified about his familiarity with the handwriting of Burton Harrison, the private secretary of Jefferson Davis, and John A. Campbell, the assistant Secretary of War for the Confederacy. Chamberlayne was then shown Exhibit 64, the letter from “W. Alston” to Jefferson Davis offering to, “rid my country of some of her deadliest enemies.” He identified that two endorsements on the letter were written by Harrison and Campbell.[13] According to a letter John A. Campbell wrote after this exhibit was first entered into evidence on May 22, “no attention was ever given to the [Alston] letter” and it was just one of many unsolicited and unanswered pieces of mail Jefferson Davis received.[14]

Henry Finnegass, a dishonorably discharged Lt. Col. from the Union army, was called as a prosecution witness. He testified he was in Montreal, Canada in February of 1865 and overheard a conversation between Confederate agents George Sanders and William Cleary. According to Finnegass, he was seated in chair when Sanders and Cleary walked in and stood about ten feet away from him. The pair discussed Lincoln’s upcoming second inauguration stating that, “Lincoln won’t trouble them much longer” and “Booth is bossing the job.” On cross examination, Finnegass acknowledged that he had never met Sanders or Clearly and that they spoke in a rather low tone.[15]

Charles Dawson, a clerk at the National Hotel, was called for the prosecution. Dawson stated he was familiar with the signature of John Wilkes Booth and was presented with Exhibit 29, the card left for Andrew Johnson at the Kirkwood House hotel. Dawson testified the note was “undoubtedly” signed by John Wilkes Booth.[16]

Charles Sweeney, a Union private with the 1st Regiment Potomac Home Brigade Cavalry, was called as a prosecution witness. Sweeney was captured by the Confederates in January of 1864 and testified that during his time as a POW he was imprisoned at Libby, Belle Isle, and Andersonville prisons. Sweeney described the harsh treatment he received at all three of the prisons noting the lack of food provided and the viciousness of Henry Wirz, the Andersonville commandant. Sweeney testified that his own brother died of starvation at Andersonville.[17] Sweeney’s testimony had nothing to do with the conspirators on trial.

James Young, a Union prisoner of war, testified for the prosecution about his time in Andersonville Prison, relating many of the same atrocities as testified by Sweeney and others. Young also spoke about his time in prison camps in Charleston and Florence, South Carolina were they were given meager and spoiled rations and prisoners were shot for no reason.[18]

John S. Young, chief of the New York Metropolitan Police detective force, was called for the prosecution and asked about his knowledge of Robert Cobb Kennedy. Kennedy was a Confederate agent who took part in a failed plot to burn New York City in 1864. Young stated that Kennedy signed a statement in his presence and the Judge Advocate asked him to read it. Young read a lengthy statement in which Kennedy sworn to the innocence of a man named Benjamin McDonald who had been accused of being part of the burning plot. After Young was finished reading it, JAG Holt stated, somewhat surprised, that it was not the confession he had expected. Holt then asked Young about the confession Kennedy had made regarding his own involvement in the burning plot. Young provided a copy of that confession but stated that he had not been present when it was given and could not testify to it.[19] The testimony regarding the burning of New York City had nothing to do with the conspirators on trial.

The affidavit signed by Robert Cobb Kennedy, attesting to the innocence of Benjamin McDonald in the burning of New York City was entered into evidence as Exhibit 70.

John Nothey, a resident of Prince George’s County, Maryland, testified that he had purchased about 75 acres of land from John Surratt, Sr., when the latter was alive. Nothey stated that he had met Mary Surratt on April 11, 1865 at her tavern at Surrattsville and that she had requested he pay her the debt that was still owed for that land purchase. Nothey also testified that Bennett Gwynn delivered a letter from Mrs. Surratt to him on April 14th but that he did not see her on that day.[20]

Dr. John C. Thomas, a physician from Prince George’s County, testified about his brother Daniel J. Thomas. Daniel Thomas had previously testified on May 18th that Dr. Mudd had told him in March of 1865 that Lincoln and his cabinet were to be killed shortly. Dr. John Thomas was the first of many defense witnesses called to counter Daniel Thomas’ claims. Dr. Thomas stated that his brother came to his house on April 23, he having recently been to Bryantown. Daniel Thomas told his brother that Dr. Mudd had been arrested and that a boot belonging to John Wilkes Booth had been found at his house. It was then that Daniel first told his brother about the words Dr. Mudd allegedly told him in March. Dr. Thomas stated that some six years earlier his brother had suffered an attack of paralysis (likely a stroke) which affected his mind. He gave his opinion that his brother’s mind was still not sound at all times ever since that attack. However, Dr. Thomas did state that he believed his brother had heard what he testified to in court, but that perhaps Dr. Mudd had said it as a joke and his brother was unable to tell the difference.[21]

Samuel McAllister, the bookkeeper at the Pennsylvania House hotel in D.C., testified that he had examined the register of his hotel and had not find the name of Dr. Samuel Mudd registered there at any time in January of 1865. Dr. Mudd’s name did appear on December 23, 1864 but no entries more recent than that contained his name. The entry on December 23, also contained the name “J. T. Mudd” who occupied the same room.[22] The purpose of this testimony was to discredit Louis Weichmann who had testified on May 13th that he was introduced to Dr. Mudd by John Surratt on around the 15th of January. Weichmann was wrong about the date. During the prosecution’s cross-examination of McAllister, John Bingham asked about the identity of the man who spent the night of April 14th in the same room as George Atzerodt. McAllister stated the book gave the name of Samuel Thomas and that he knew nothing more about it as he was asleep when Atzerodt and Thomas came in. The government was still under the mistaken impression that Atzerodt was joined by one of the other conspirators (possibly Michael O’Laughlen, Edman Spangler, or even John Surratt) that night.

Jeremiah T. Mudd, a second cousin of Dr. Samuel Mudd, testified that he accompanied Dr. Mudd on his December 23, 1864 trip up to Washington. Jeremiah stated that the two men stayed overnight at the Pennsylvania House hotel and that Dr. Mudd’s reason for the trip was to purchase a stove, which he did on December 24th. The two were with each other almost the whole trip according to Jeremiah, except for some time on the 23rd when they separated near the National Hotel. Surprisingly, the government did not ask about this time Dr. Mudd was away from Jeremiah because they still believed Louis Weichmann’s misdated testimony that Booth met Mudd in D.C. around the 15th of January. Jeremiah testified that Dr. Mudd was known as a good citizen in Charles County and that he had never heard him say anything disloyal. However, Jeremiah did admit that Dr. Mudd had expressed some sentiments opposed to the policy of the Lincoln administration.[23] When Thomas Ewing, Dr. Mudd’s lawyer, asked Jeremiah about John Wilkes Booth’s presence in Charles County in 1864, Assistant Judge Advocate John Bingham objected. This objection, and the many that had preceded it, bothered Ewing, and he responded to the court with a thinly veiled criticism of Bingham and his methods:

“May it please the Court, I know it is the object of the Government to give the accused here liberal opportunities of presenting their Defense. I am sure the Judge Advocate does not intend, by drawing the reins of the rules of evidence tight, to shut out testimony which might fairly go to relieve the accused of the accusations made against them. I think it is better not only for them, but for the Government, whose majesty has been violated, and whose law you are about to enforce, that there should be liberality in allowing these parties to present whatever Defense, they may offer.”[24]

Francis Lucas, a huckster living near Bryantown, testified that he was in D.C. on December 23 and 24, 1864. Lucas stated that on December 24th Dr. Mudd approached him two or three times asking if he could take a stove down to Bryantown in his wagon. Lucas told Mudd he would if he could but later informed the doctor that he could not.[25] This testimony supported the words of Jeremiah T. Mudd who stated that Francis Lucas sold poultry in D.C. and offered to take the stove back down with him if he sold enough to make room for it. This was all meant to prove that Dr. Mudd’s reason for travelling to D.C. in December of 1864 was to buy the stove, rather than to meet John Wilkes Booth.

John C. Thompson, a son-in-law of Dr. William Queen of Charles County, Maryland, testified that he met John Wilkes Booth at his father-in-law’s home in November of 1864. According to Thompson, Booth possessed a letter of introduction to Dr. Queen from a man named Martin in Montreal. During his visit with his father-in-law, Booth expressed his desire to buy some land in the region. Thompson testified that he introduced Booth to Dr. Mudd at St. Mary’s Church on the Sunday of his visit. Thompson stated he did so without any planning and that Mudd just happened to be in a group of men assembled around the church when he came up with Booth. Thompson also recalled Booth visiting with his father-in-law again in December of 1864.[26] This defense testimony was meant to show that Dr. Mudd’s introduction to John Wilkes Booth was accidental and stemmed from the actor’s cover story that he was looking for land in the area. This ran counter to the earlier testimony of Eaton Horner who testified on the 18th that Samuel Arnold had told him that Booth had letters of introduction to both Dr. Queen and Dr. Mudd.

At the conclusion of Thompson’s testimony, the court adjourned at around 5 o’clock.[27]

Recollections

“The commission met this morning as usual. There was the usual crowd notwithstanding the rain that continued all day. Nothing transpired. There is much delay by the Judge Advocate Bingham who is constantly objecting to the questions asked by the Counsel.”[28]

In his later memoirs, General Doster, lawyer to Powell and Atzerodt, recalled Assistant Judge Advocate Bingham’s behavior in court:

“As regards the conduct of the judge advocates, that of Mr. Holt was courteous and moderate throughout, so was that of Colonel Burnett. This, however, cannot be said for Mr. Bingham. His mind seemed to be frenzied and his conduct violent.”[29]

Jane G. Swisshelm, an anti-slavery and women’s rights journalist, attended the trial on this day. On the day after Mary Surratt was executed, Swisshelm penned a letter that was published in the Pittsburg Commercial. In that letter, Swisshlem recalled her observations of and interactions with Mrs. Surratt during this day of the trial:

“…Her face, and indeed her whole figure, while on trial, was soft, rounded, tender and motherly. Her large gray eyes alone gave indication of reserved strength. Her behavior, during that long and terrible ordeal, was full of delicacy and dignity. She made no scenes, as a weaker or vain woman would have done…All the long, hot days she sat with her heavy mourning veil down, and a large, palm-leaf fan held between her face and the crowds who gathered and rushed and struggled to gaze at her, as if she had been an alligator – hundreds of persons in these crowds making the most insulting remarks in her hearing.

Your readers are, no doubt, familiar with the form of the court room, and know that her position was in the southwest corner facing the east, and that a door leads in from an ante-room on the south, about four feet from the railing behind which she sat. On my one visit I had a chair close to the wall behind this door and the railing, so that I was within less than two feet of the rail with orders to keep that place clear; but the press at the door for entrance was so great that I gradually moved my chair until it was close to the rail, and sat there an hour before being discovered. During all that time she leaned her head wearily against the wall, and by changing hands kept her hands steadily before her face, and every few minutes a low, stifled moan escaped her. Man and woman stood a tiptoe, and stretched and strained, or, having gained entrance, stood cooly and made such remarks as ‘Where’s Mrs. Surratt?’ ‘I want to see her!’ ‘Oh, goodness, just look if she isn’t pretending to be modest!’ ‘I wish I could see her face better!’ ‘Isn’t she a devil?’ ‘She looks like a devil!’ ‘Hasn’t she a horrid face?’ ‘I hope they’ll hang her – tee, hee, hee!’ All these remarks, and more such, some of them again and again, and often accompanied by coarse laughter, I heard during the two hours and a half I sat near her, and she must have heard them as distinctly as I did. They were evidently meant for her.

It appeared to me so cruel and so cowardly thus to insult a prisoner in chains that I could not refrain from answering, and several times said: ‘She has not a bad face. She has a good face, and if she had not, it is cowardly to insult her!’

She dropped her fan, and looked at me with such an expression of gratitude as I shall never forget. I looked full into her eyes; mine were not dry, while hers filled with heavy tears. Several asked me if ‘I was a friend of Mrs. Surratt,’ so strange did any pity for her appear.

Once she arose and made an effort to touch her counsel with her fan as he passed out of the door. I asked her if she wished to speak to him, and on offering to have him called, she thanked me in a low, sad, sweet tone. I became a suspicious character, and an officer came and planted himself between us to see that there was no communication.”[30]

Newspaper Descriptions

“Objections from Assistant Judge-Advocate Bingham were as frequent today as yesterday, interrupting every fresh point of the evidence for the defence, and often couched in the most singular language – describing some of the questions as the smallest effort to defend a criminal seen since the flood, etc. Mr. Ewing at last remonstrated against this line of conduct in a few mild remarks, urging that it was hardly consistent for the prosecution to compel an adherence to the strict technical rules of evidence on the part of the defence. Judge Holt rejoined that he wished to allow the greatest liberality in admitting evidence, and that he hoped that all frivolous objections, from whatever source they might come, would be overruled by the court, as the only object of the trial was simple and impartial justice. During the rest of the afternoon, Judge Bingham’s captious objections were heard less frequently.”[31]

Mrs. Surratt

“Mrs. Surratt sits veiled, but a powerful glass to-day disclosed the fact that she was not weeping, as many suppose but was active with her eyes gazing about the court-room with the same heartless indifference to her wretched condition displayed by the male criminals.”[32]

“Mrs. Surratt sits in the same position, her head leaning against the wall, and her veil drawn over her face – her large palm-leaf fan in her hand.”[33]

“Mrs. Surratt seems to have lost all hope within the last 48 hours, and sits crouched in her corner with face entirely concealed.”[34]

Lewis Powell

“Payne, in his usual seat, was dressed in the mixed gray shirt which was worn by him yesterday.”[35]

“Payne continues defiant of eye, and erect in carriage, but it is noticed that his lips grow bloodless day by day.”[36]

“The prisoner Payne has the chills to-day.”[37]

David Herold

“Herold, in his usual seat at the end of the bench, looks dirty and rough, his thin beard giving his face a very dirty look.”[38]

“Herold simpers less, and seems gradually to be coming to a sense of the gravity of his situation.”[39]

George Atzerodt

“Atzerodt has that same villainous cutthroat appearance, his horrid countenance being readily noticed by the numerous visitors at the Court.”[40]

Dr. Mudd

“Dr. Mudd who has heretofore worn a white handkerchief about his neck appeared without it yesterday and to-day.”[41]

Samuel Arnold

“Arnold stood up, leaning against the rail, during a great portion of the time when the proceedings were being read.”[42]

“Perhaps the most entirely cheerful face in the line is that of Arnold.”[43]

Michael O’Laughlen

“O’Laughlin, who sat by the side of Spangler, looks dejected and miserable. During the time the evidence was being read which related to him he sat with his eyes fixed upon the floor.”[44]

“O’Laughlin, too, continues to look entirely despondent, despite the strong effort made yesterday by the defence to prove an alibi for him, both on the night of the assassination and on the previous night, at Secretary Stanton’s.”[45]

Edman Spangler

“Spangler presents the same appearance.”[46]

“Spangler, too, seems to be recovering in his spirits.”[47]

Visitors

“As it is raining this morning, and rather muddy about the neighborhood of the Penitentiary, the probability is that the curious will not trust themselves into the court room to-day. We are charitable enough to believe that they have more appreciation of their own comfort.”[48]

“The court-room was densely crowded this morning – a large portion of the audience being ladies. Every passage-way and every inch of standing room was occupied.”[49]

“The interest in the trial of the Southern Confederacy by the military commission is on the increase; the crowd was denser to-day than ever. The morbid curiosity for sight-seeing led many delicate ladies and children to be crushed and squeezed to the point of fainting.”[50]

“Among the visitors to-day is [Philadelphia newspaper publisher] J. Barclay Harding, Esq., and ladies of Philadelphia. Mrs. Jane G. Swisshelm is present, and occupies a seat inside the rail. As on yesterday, the room is crowded with ladies, but they are not so irrepressible in the matter of talk as was the gathering yesterday; and the reporters find themselves able to prosecute their labors less disadvantageously from the buzz of conversation.”[51]

“Among the spectators this afternoon is U.S. Senator John A. Creswell, of Maryland; also, Hon. Mr. [John F] Farnsworth, of Illinois.”[52]

“As the prisoners were brought in the spectators pushed forward as usual, and the ladies especially crowded with such eagerness about the bar of the dock – uttering lively ejaculations at the time – as Payne entered that he visibly lost countenance for the moment, blushing like a girl.”[53]

It appears that noted photographer Alexander Gardner attended the trial today, possibly accompanied by his daughter Eliza and son Lawrence. A trial pass dated May 26 was made out for “Mr Gardner & two friends.” On an accompanying piece of paper, Eliza Gardner wrote:

“Card admitting to Conspiracy trial held at the old arsenal. I went once and saw Mrs Suratt and the other poor creatures[.] Father made a photograph of the execution”[54]

Another trial pass made out for this date was for Augustus Seward, son of Secretary of State William Seward.[55] Augustus had previously visited the court on May 18th and testified on May 19th about grappling with Lewis Powell after the latter attacked his father.

Yet another pass made out for this date was for Rhode Island representative Thomas Jenckes.[56] This pass was made out by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and granted the bearer admittance for the entirety of the trial. If and when Jenckes used this pass is unknown.

Previous Session Trial Home Next Session

[1] John F. Hartranft, The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution, as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft, ed. Edward Steers, Jr. and Harold Holzer (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 106.

[2] William C. Edwards, ed., The Lincoln Assassination – The Court Transcripts (Self-published: Google Books, 2012), 549.

[3] Henry Kyd Douglas, I Rode with Stonewall (Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publications, 1961), 325.

[4] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 550.

[5] Ibid., 550.

[6] Ibid., 550 – 552.

[7] Ibid., 552 – 553.

[8] Ibid., 553 – 555.

[9] Ibid., 555 – 561.

[10] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[11] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[12] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 561 – 563.

[13] Ibid., 563 – 564.

[14] William C. Edwards and Edward Steers, Jr., ed, The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 323.

[15] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 564 – 567.

[16] Ibid., 567.

[17] Ibid., 567 – 569.

[18] Ibid., 569 – 571.

[19] Ibid., 571 – 573.

[20] Ibid., 573 – 574.

[21] Ibid., 574 – 577.

[22] Ibid., 577 – 580.

[23] Ibid., 580 – 586.

[24] Ibid., 584.

[25] Ibid., 586 – 587.

[26] Ibid., 587 – 590.

[27] Hartranft, Letterbook, 106.

[28] August V. Kautz, May 26, 1865 diary entry (Unpublished diary: Library of Congress, August V. Kautz Papers).

[29] William E. Doster, Lincoln and Episodes of the Civil War (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1915), 280 – 281.

[30] Holmes County Farmer (Millersburg, OH), July 20, 1865, 2.

[31] Boston Daily Advertiser (Boston, MA), May 27, 1865, 1.

[32] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[33] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[34] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[35] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[36] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[37] The World (New York, NY), May 27, 1865, 8.

[38] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[39] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[40] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[41] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[42] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[43] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[44] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[45] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[46] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[47] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[48] Daily Constitutional Union (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 1.

[49] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[50] The World (New York, NY), May 26, 1865, 1.

[51] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[52] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[53] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[54] Heritage Auctions, Political & Americana Auction: August 25 – 26, 2018 (Dallas: Heritage, 2018).

[55] Heritage Auctions, The Dr. John K. Lattimer Collection of Lincolniana (Gettysburg: Heritage, 2008).

[56] Edwin Stanton, Pass to the Military Commission, May 26, 1865 (Allen County Public Library, Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection).

The drawing of the conspirators as they were seated on the prisoners’ dock on this day was created by artist and historian Jackie Roche.

Pingback: The Trial Today: May 26 | BoothieBarn

Thank you for providing the links to the actual testimony of each witness. I get so many interesting tidbits of information from the testimony. While I do not read each testimony, there are those whose testimony is of interest to me and help me to see where the prosecution or defense was going.

It seems as if Stanton had some blank or pre-signed by Hunter trial passes since he provided one to Mr. Jenckes.

I know it is generally accepted that Weichmann wrote the Nothey letter for Mary on the 14th. Comparing the general handwriting and some specific letter construction, the written text does not appear to be that of MES, except for the last line, squeezed in at the bottom of the page, at which MES describes herself as the “administratix” of her husband’s estate. I presume MES had Gwynn deliver the letter to Nothey as it was late in the day and MES wanted to get back to the city. Perhaps she was anxious about the visitor she would have later in the evening??

It must be kept in mind that no testimony whatsoever emerged at the Conspiracy Trial that Mary Surratt expected the visitor who showed up at the boardinghouse at 9 p.m. on the night of the murder. The only “evidence” thereof came from Wiechman’s voluntary affidavit which he prepared one month after the conclusion of the trial when he found he had become a pariah in the wake of Mrs. Surratt’s execution. It is quite interesting to note how his memory had improved. At the trial he unmistakably averred he had no idea of the identity of that visitor, but one month later clearly recalled not only that it had been Booth but that Mrs. Surratt had voiced her expectation thereof on their return trip that night from Surrattsville.

About the visitor, Weichmann wrote (in his book) that when the detectives had departed on the morning of April 15th Anna Surratt cried out, “Oh, Ma! Mr. Weichmann is right; just think of that man (John W. Booth) having been here an hour before the assassination. I am afraid it will bring suspicion upon us.”

It is axiomatic that a witness’s recollections become less reliable with the distance of time. Wiechman wrote the manuscript to his book more than 30 years after the Conspiracy Trial, during which decades he had had ample opportunity to absorb information/suppositions from a variety of sources so that he could compile a justification for the “patriotic” stance he had taken at that tribunal. But even a cursory comparison of the testimony he gave at the Conspiracy Trial with the affidavit he swore out just one month later and the testimony he offered at the John Surratt Trial will reveal numerous blatant, substantive fabrications.

The details which you have highlighted first emerged in an open letter Wiechman had published on July 15, 1865–just 8 days after the execution of Mrs. Surratt–in the Philadelphia Sunday Dispatch, offered in response to an attack which had been made on his credibility. Less than one month later, Wiechman felt the urge to commit this new information into a voluntary affidavit addressed to one of the former prosecutors of the Conspiracy Trial, JAG H. L. Burnett.

How curious that this explosive evidence, which his memory had managed to suppress during both the numerous intense pre-trial interrogations and the searching examinations to which he was subjected on each of the 4 different occasions he had taken the stand, suddenly flooded into his consciousness within days of the verdict.

On May 13, 1865, Wiechman testified he had no clue as to the identity of the 9 p.m. visitor. Yet a mere two months later he vividly recalled Anna Surratt’s supposed outcry just hours after the murder that it had been Booth. Whatever motivation drove Wiechman, the conclusion is inescapable: he had lied either on the stand or in his affidavit.

What’s going on with Reverdy Johnson never being in attendance? I know he had seconds there, but his presence might have helped his client. I wonder if he was sick or if the Senare was in session and he had to be there?

Carol,

It appears that Reverdy Johnson took great umbrage to the opposition he faced when he was admitted to represent Mrs. Surratt on May 13 (https://boothiebarn.com/the-trial/may-13-1865/). Johnson only returned to the court on May 15 and 18. From then on, the only assistance he provided Mrs. Surratt was to write an argument against the jurisdiction of the court which was read by John Clampitt, another of Mrs. Surratt’s lawyers, at the end of the trial.

I forgot to add, another one of the defense lawyers, William Doster, agreed with you that Johnson’s absence worked against Mrs. Surratt: https://boothiebarn.com/the-trial/may-19-1865/#doster