I am conducting an ongoing review of the seven-part AppleTV+ miniseries Manhunt, named after the Lincoln assassination book by James L. Swanson. This historical review covers the third episode of the series, “Let the Sheep Flee.” This analysis of some of the fact vs. fiction in this episode contains spoilers. To read my reviews of earlier episodes, click the hyperlinked episode numbers that follow: Episode 1, Episode 2.

Episode 3: Let the Sheep Flee

In this episode of Manhunt, we see Booth and Herold, guided by Oswell Swann, finally make it to Rich Hill, the home of Confederate sympathizer Samuel Cox. The man offers to help the fugitives by putting them in contact with the “River Ghost” (aka Thomas Jones). Swann leads them to the pine thicket, where the two men wait. When the River Ghost does appear, he tells them the time is not yet right to cross the Potomac River. On the Stanton front, the Secretary of War’s asthma is greatly impacting his health. With grave matters of racial injustice playing out on the streets of Washington, Stanton defies his doctor’s and his wife’s orders not to exert himself. His conflicts with President Johnson increase, as the President appears to go back on his word to punish the South and its leaders. In Richmond, Major Eckert, assisted by members of the USCT, searches the remnants of Confederate offices until they found a cipher cylinder. With the key phrase conveniently taped to the bottom, Eckert can now unscramble the message found at the Surratt Tavern. The telegram from “The Office of Jefferson Davis” to John Surratt says, “Come Retribution.” Meanwhile, Lafayette Baker’s agent in Canada, Sandford Conover, is on the hunt to track down Surratt, the missing conspirator. Conover is given a clue about Surratt’s whereabouts in Montreal from a well-connected Confederate operative named George Sanders. Once Stanton is able to solve the clue, Conover makes contact with Surratt, who is hiding out as a priest. He sends word to Stanton, who travels up to Montreal to interrogate Surratt personally about Booth’s whereabouts. But, when Conover attempts to take Surratt into custody, the conspirator overpowers him and leaves him tied up for Stanton to find. Surratt successfully flees Canada, leaving Stanton without his main lead as to Booth’s whereabouts. After learning that Surratt’s ship to freedom was chartered by George Sanders, Stanton and Baker consider that he may be the mastermind behind the assassination. In the closing scenes, Sanders menacingly talks to a room full of Confederate supporters about the second chance Booth has given them and the possibility of restarting the slave trade. This is juxtaposed with Mary Simms receiving a deed in the mail from the War Department, giving her her own land grant in Charles County, Maryland.

Before getting into my review, I want to pivot to something different for a bit. Have you ever heard of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs? They are a collection of dinosaur and mammalian sculptures located in Crystal Palace Park in southeast London. The dinosaurs were unveiled in 1854 with much fanfare as the first attempt to create life-sized models of dinosaurs and other extinct creatures. They proved incredibly popular with the public, drawing visitors to Crystal Palace Park and inspiring a new generation to take up the fairly new field of paleontology. Even now, 170 years later, these sculptures are a treasured attraction at the park, as can be seen in this video of some recent restoration that has been done on one of them:

The Iguanodon sculpture at Crystal Palace Park is a well-known example of the ever-evolving nature of scientific understanding. When the first few incomplete fossils of the Iguanodon were found, paleontologists discovered a small spike-like bone. After analyzing the bone, it was determined that this spiky bone rested on the nose of the Iguanodon in much the same way as a rhinoceros horn. Using this information, the sculptor rendered his Iguanodon sculptures with that same small nose spike.

With the discovery of more fossils in the Iguanodon genus, it was realized that this spiky bone was not a part of the dinosaur’s head at all. Instead, we discovered that this spike is located on the Iguanodon’s hand, acting as a modified thumb. This thumb spike is believed to have helped the Iguanodon protect itself against predators and possibly have been used as a tool to help break open fruits and seeds.

You’re probably wondering why I’m opening a review of Manhunt with this paleontological fun fact. Well, it’s because I couldn’t help but think of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs while watching this week’s episode of the series. They actually have more in common with each other than you might think. Both the sculptures and the series are beautiful pieces of art. I have no doubt that, like the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, Manhunt will inspire others to learn more about the past. I can tell you already that my website hasn’t seen this much daily traffic since the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination in 2015. Manhunt is definitely increasing awareness and interest in this crucial event in American history.

Beyond artistry and interest, however, I kept thinking about these Iguanodons with the incorrect nose spike. The bone itself was a real piece that belonged in those sculptures, but they were in the wrong place. In truth, most of the decisions about the Crystal Palace Iguanodon’s appearance are now out of date, and the sculpture bears very little in common with our current understanding of these prehistoric creatures. This is true for the other dinosaur sculptures as well. The bones might be there, but they are just in the wrong places.

That was the same takeaway I had from episode 3 of Manhunt, “Let the Sheep Flee.” Like the Crystal Palace Iguanodon, the end result of this episode bears very little in common with our current understanding of the historical record. What few correct bones there are in episode 3, are largely in the wrong places.

The first two episodes of the series contained several areas of dramatic license, exaggeration, and alterations. While unhappy with some of the changes in those episodes, I still was able to see how the series was attempting to stay true to the spirit of the history, as author James Swanson said in an interview for CSPAN about the series. In episode 3, however, I found myself frustrated as the series appeared to diverge even further from historical truth.

I am also concerned that this series is embracing the unproven theory that the Confederacy was responsible for Lincoln’s death. I worry about the effect this will have on a general audience without enough background knowledge on the subject to be able to identify this theory as purely speculative and totally unproven. While the real Stanton and others in 1865 believed that Jefferson Davis and other high-ranking officials in the Confederacy had a hand in Lincoln’s death, no reliable evidence has even been found to support this conclusion. The result of the conspiracy trial showed how weak the government’s case was against these absent co-conspirators, as they had to rely on perjured testimony and fraudulent letters in order to prove a meaningful connection between Booth and Confederate agents. In the almost 160 years since that time, no big smoking gun has been discovered connecting Booth to the Confederacy at large. As a book, Manhunt does not embrace this theory, and I’m concerned that, in an effort to bring more drama to an already compelling story, the series may make the work of historians harder rather than easier. But, like everyone else, I have not seen the complete series yet. My fears may easily prove to be unfounded.

Before diving into some of my criticisms and my analysis of the fact vs. fiction in this episode, I want to highlight things that I liked about it. Even though this was my least favorite episode so far, there were still a few things that I think the show should be commended for.

- The “Tactical” Decision

Edwin Stanton is greatly affected by the cold-blooded murder of a Black War Department soldier by a white resident at a park just outside his home. The event causes him to recall meetings he had with the President and Frederick Douglass about the idea of recruiting Black soldiers and the government’s role in helping fugitive slaves if the Union were to lose the war. These scenes show a Lincoln consistently sympathetic to the plight of Black Americans, both free and enslaved.

While the real Lincoln tried his best to be mindful of the injustices faced by Black Americans, he was first and foremost a pragmatic politician, intent on his goal of ending the war and reuniting the Union. He was also influenced by the prevailing racial prejudices and white supremacist beliefs of his time. In August of 1862, Abraham Lincoln invited a small delegation of Black ministers to the White House in an attempt to gain support from them for his plan of Black emigration. During that meeting, Lincoln read a formal statement in which he declared that:

“You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss, but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think your race suffer very greatly, many of them by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word we suffer on each side. If this is admitted, it affords a reason at least why we should be separated.

…We look to our condition, owing to the existence of the two races on this continent. I need not recount to you the effects upon white men, growing out of the institution of slavery. I believe in its general evil effects on the white race. See our present condition—the country engaged in war!—our white men cutting one another’s throats, none knowing how far it will extend; and then consider what we know to be the truth. But for your race among us there could not be war, although many men engaged on either side do not care for you one way or the other. Nevertheless, I repeat, without the institution of slavery and the colored race as a basis, the war could not have an existence.

It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated.”

David Blight, the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, calls this meeting “Lincoln’s worst racial moment.” The President blamed the Civil War on the presence of Blacks in America and attempted to convince the group that the only future for the Black race was to leave America and settle elsewhere. When Frederick Douglass learned of this meeting and that the President had embraced the colonization movement that sought to evict Black Americans from their country of birth, he was furious and understandably lambasted the President in his speeches and newspaper columns.

Yet, even as the President was attempting to encourage Black leaders to support emigration, he was also secretly working on the draft of his Emancipation Proclamation. While the Emancipation Proclamation was an act of moral conviction on Lincoln’s part, as he had always seen slavery as a terrible evil, the actionable part of the Proclamation was the authorization to allow Black men to become soldiers. This was a well-thought-out “tactical” decision, as Tobias Menzies’ Stanton states in this episode. The real Edwin Stanton had also been looking for ways to utilize the thousands of “contrabands” (i.e. escaped slaves) who had found refuge within the Union lines. Stanton had advocated for the defensive use of these men to help with the war effort, and after the Emancipation Proclamation, he hoped to have “200,000 negroes under arms before June [1863] – holding the Mississippi River & garrisoning the forts so that our white soldiers can go elsewhere.” That timeline proved to be unrealistic, but by the end of the war, almost 180,000 Black soldiers had served in the Union Army at one time or another. More importantly, they were not resigned to only defensive assignments but proved the equal of any white regiment for their bravery in several battles.

I’m glad that this series took a moment to explain how the Emancipation Proclamation was a great tactical decision by President Lincoln and how it was supported by the Secretary of War. While Frederick Douglass did not meet Stanton or Lincoln until August of 1863, when he met with each man separately concerning the unequal pay between white and Black soldiers, he was still a strong supporter of the Emancipation Proclamation and the recruitment of Black soldiers.

- Booth’s CSA Dream

I liked the opening scene of the episode, which shows Booth taking the oath of office as the second president of the Confederate States of America. It is the culmination of the assassin’s hard work and shows how high the South holds him in esteem. It’s all a daydream of Booth’s, of course, as he is quickly brought back to reality by Oswell Swann literally “taking the piss” out of Booth’s illusion. This scene was an effective way to show us the severity of Booth’s delusions of grandeur, a common theme in this episode. Right after leaving his daydream, we see David Herold reading Booth’s diary and complimenting Booth on his writing. Of course, in reality, it’s unlikely Booth had written anything worthwhile in his small datebook at this point during his escape (which would still be the night of April 15-16). In fact, the only reason Booth turned to writing in his “diary” at all was because his actual last manifesto justifying his actions was burned on the night of the assassination by the man he had entrusted it to. It was only after getting access to newspapers about his crime and seeing his words suppressed that Booth was forced to make do with the small pocket datebook he carried. Still, the series accurately demonstrates how Booth was writing for an audience and for posterity’s sake. This Booth claims that copies of his diary will be in every school and library in Richmond (and, assumedly, the whole South) someday. Like the dream sequence, this shows us the vanity of John Wilkes Booth.

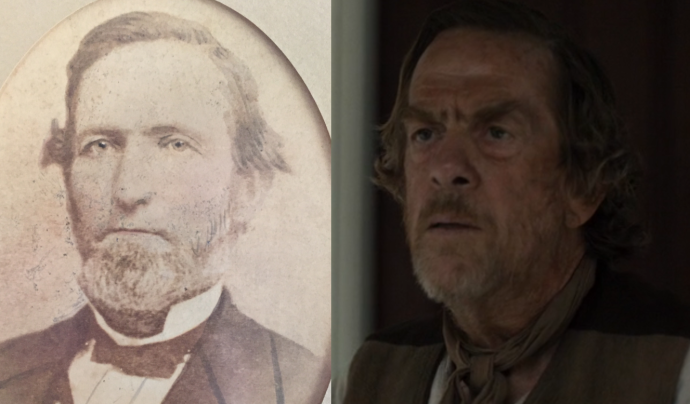

- Good Lookalikes for Samuel Cox and Joseph Holt

As with President Johnson, I have to give the casting and makeup departments high marks for their choices in depicting two historical characters introduced in this episode. The actor playing Samuel Cox looks quite a bit like the real owner of Rich Hill.

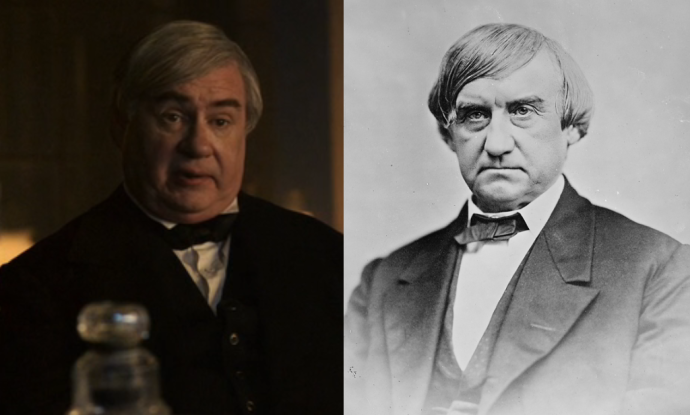

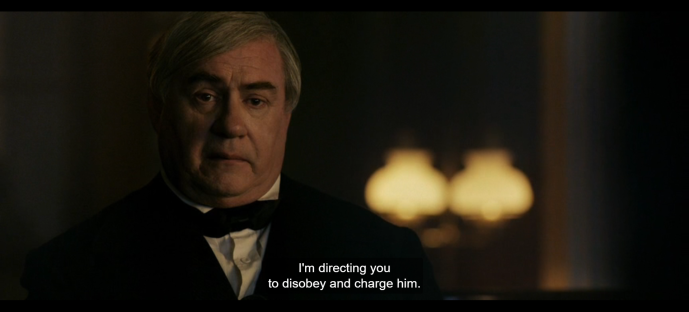

I was also very happy to see actor John Billingsley being referred to as “Joe” by Stanton in this episode. Up until just a day or two ago, he was still listed on IMDB as playing Edward Bates, the Attorney General under Lincoln who had departed the cabinet in 1864 and was not involved in the drama that followed the assassination. Luckily, both the dialogue in this episode and his updated entry on IMDB verify that he is playing Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt. The team did a great job making him up for the part.

If you’re a fellow Trekkie like me, you might recognize Billingsley from his time playing Phlox, the lead physician in the Scott Bakula-led Star Trek series Enterprise from the early 2000s. He wears considerably less makeup and prosthetics in his role of Holt than he did as everyone’s favorite Denobulan.

In addition to the excellent casting and makeup, I enjoyed the brief scene between Stanton and Holt in that it provided us with great foreshadowing of the trial of the Lincoln conspirators yet to come. In this episode, Stanton appeals to Holt to ensure that the man responsible for killing the Black soldier is held accountable. He tells Holt to disobey any order to release the man and that he needs a conviction. Holt states that he understands the sentiment but isn’t sure the “precedent extends to that.” I’m confident that Stanton’s need for a conviction and influence on Judge Holt will be shown again in the closing episode(s) of the series.

- David Herold

I have to give credit to writers and actor Will Harrison for the portrayal of David Herold in these episodes. Even though he was with Booth during the entirety of his escape, Davy is often overlooked or made painfully one-dimensional in texts about the assassination. Many books try to portray Davy as nothing more than an immature child, too dull-witted to realize the implications of his choices. But this portrait of Davy has never been accurate. Yes, Davy was portrayed as dim-witted by witnesses at his trial, but this was a gambit by his own defense team. With such a mound of evidence against their client, the best they could do was attempt to prove that Herold was not culpable for his own actions. Attempting to depict Davy as slow-witted failed to prevent his death and has plagued representations of him ever since.

In this series, though, David Herold is more complex. While it is clear that Davy is still very devoted to the famous actor, through the performance of Will Harrison, we are starting to see the cracks forming in Davy’s devotion. The unequal relationship between Booth and Herold is very evident, and my favorite parts of episode 3 are the scenes between Oswell Swann and Herold, where the former forces Herold to contemplate his own importance to Booth.

While there is no evidence that any such conversations occurred, mainly because Swann didn’t know the identity of the men he guided, the sentiment behind Swann’s remarks is real enough. The real David Herold must have considered his continued presence by Booth’s side as the escape went on. On his own and without the broken-legged Booth to slow him down, Davy might have been able to make his escape into the deep South or even to Mexico. He must have considered this possibility, especially during the nights in the pine thicket or as he singlehandedly rowed them both “across” the Potomac River. Twice.

I’m very much enjoying seeing Will Harrison’s Herold continue to grapple with his choices and his reasons for staying with Booth.

Now, let’s examine some of the instances of dramatic license and historical inaccuracy that plagued this third episode.

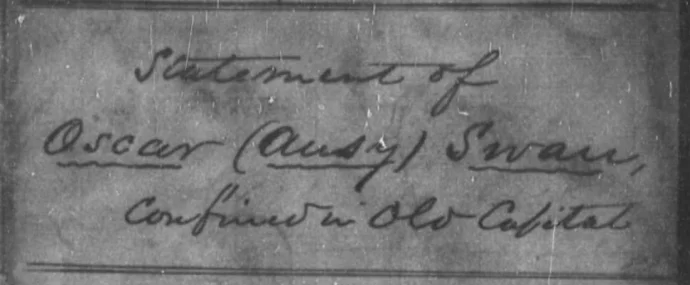

1. Oswell Swann

I want to start off by saying that Roger Payano’s performance as Oswell Swann has been excellent. He is clearly a talented actor and gives a strong performance in this and the previous episode. My wife Jen expressed to me how much she likes the character of Oswell Swann, and I have to agree. If nothing else, the writers created an interesting character that Payano plays well.

The issue is that a lot of dramatic license has been taken with the historical figure of Oswell Swann. To return to my Iguanodon example from earlier, only a few bones of the actual man and his interaction with Booth and Herold are present in what the series has portrayed. A lot of the little stuff can be forgiven, such as the trio traveling during the daytime, the depiction of Swann taking the fugitives’ guns, or even showing Swann escorting the men to the pine thicket (Cox’s farm overseer Franklin Robey actually did that).

However, the series shows two big changes to the real Swann that I vehemently disagree with. They are the idea that Swann knew who Booth and Herold were when he was escorting them and, worst of all, that he was actively complicit in their escape. The most disturbing part of the series’ portrayal of Swann is how they have turned the mixed-race tobacco farmer with a wife and eight children into a willing and active participant in the Confederate underground. For a series that should otherwise be commended for championing Black representation in this story, I feel it is a gross miscarriage of history to place Swann on the side of those who would actively work to oppress him. There is no evidence that the real Swann assisted the Confederate underground in Southern Maryland. He was not part of the “secret line” of Confederates, as the Mudd and Cox in this series both claim.

Oswell Swann was an innocent farmer who had no inkling as to the identity of the two lost men who stumbled across his home at around 9:00 pm on the evening of April 15. He generously fulfilled their request for some bread and a drink before agreeing to help take the men (one of whom was suffering from a broken leg) to their intended destination for a small fee. There was nothing nefarious in the deed. It was merely the act of a poor, mixed-race farmer in the backwoods of Charles County, happy to make a few dollars for a simple job. When the real Swann eventually learned that the assassin of President Lincoln had suffered a broken leg, he earnestly made contact with the Union authorities to tell them of the two men he had guided to Rich Hill. He held back nothing.

In one of my earliest posts on this blog, I documented the known facts about the life of Oswell Swann and his interaction with the fugitives. Though that over-a-decade-old post is not as refined as my more recent work, I still believe the piece has valuable information about Oswell Swann. I highly encourage you to read that post and learn the real story of Oswell Swann.

As much as I enjoyed parts of the series’ version of Oswell Swann, I do not like how he is portrayed on the side of the bad guys in this story. There were plenty of real bad guys for the series to choose from. In my opinion, Oswell Swann deserves much better than to be depicted as a man who actively helped Confederates and knowingly assisted John Wilkes Booth, even if it was somewhat reluctantly.

2. Not Everyone was in the Confederate Secret Service

I have a feeling that one of the biggest misconceptions that will come out of this miniseries is the widespread belief that the Confederacy had one of the greatest spy and underground networks of all time. Everyone we have seen help Booth on his escape so far has been part of the “secret line.” It apparently furnished John Surratt up to Montreal in record time, and Samuel Cox offered the same to Booth when he arrived. If the Confederate Secret Service was effective enough to successfully transport the most wanted men in America completely through the Union, one wonders how the Confederacy managed to lose the war in the first place.

In this episode, Samuel Cox takes Booth and Herold down into his not-so-secret windowed basement filled with documents, maps, a cipher cylinder, and even a telegraph machine. How Cox got a telegraph line installed in his home without everyone in the neighborhood, including the regular Union patrols, noticing it is never explained. From this well supplied bunker, Cox describes how, as a member of the CSS, he helps to conduct a secret war.

Yes, the so-called Confederate Secret Service existed, and yes, they did enact covert actions against the Union during the Civil War. But the actual CSS was not all that organized. While there were leaders in both the South and up in Canada, they operated more like different terrorist cells than a unified front. Each group largely made its own plans based on their own judgments of what would help the Confederacy. In reality, in isolated or unimportant places like Southern Maryland, there was no real CSS presence at all. While Samuel Cox was well known as a Confederate sympathizer and had organized a pro-Southern militia in Charles County during the secession crisis, I don’t know of any evidence that he was considered a member of the Confederate Secret Service. The greatest accomplishment of the Confederate Signal Corps in Southern Maryland was the successful smuggling of mail and men across the Potomac River. Cox’s foster brother, Thomas Jones, was the chief agent in this venture and later wrote proudly of his work. This is why Cox put the fugitives under the care of Jones when they sought out his help. There wasn’t much Cox could do for the pair on his own, and even men like Thomas Jones were little more than big fish in a small pond who had no real influence or connection to the Confederacy at large.

The Union knew that places like Southern Maryland were overrun with Confederate sympathizers who were aiding and abetting the enemy in their own small ways, but their crimes were extremely minor compared to real CSS activities like the guerilla raid on St. Albans, Vermont, or the plot to send Yellow Fever infected clothing to major Northern cities in hopes of starting an outbreak.

While the series may like the intrigue of a well-oiled and sinister Confederate Secret Service machine in Southern Maryland helping Booth to escape, the true story is far more mundane than menacing. Booth did not get the help of an elaborate spy network but from a few select Confederate sympathizers who were willing to do the bare minimum to help him get into Virginia.

3. George Sanders

I truthfully didn’t know where to start on the Montreal portions of this episode. The only correct bones in these scenes are that John Surratt, Jr. did hide out in the Canadian city after the assassination, some detectives did travel there in search of him, and that a pro-Confederate meddler named George Sanders often resided in Montreal. Beyond that, however, everything that takes place in Canada in this episode is fictitious.

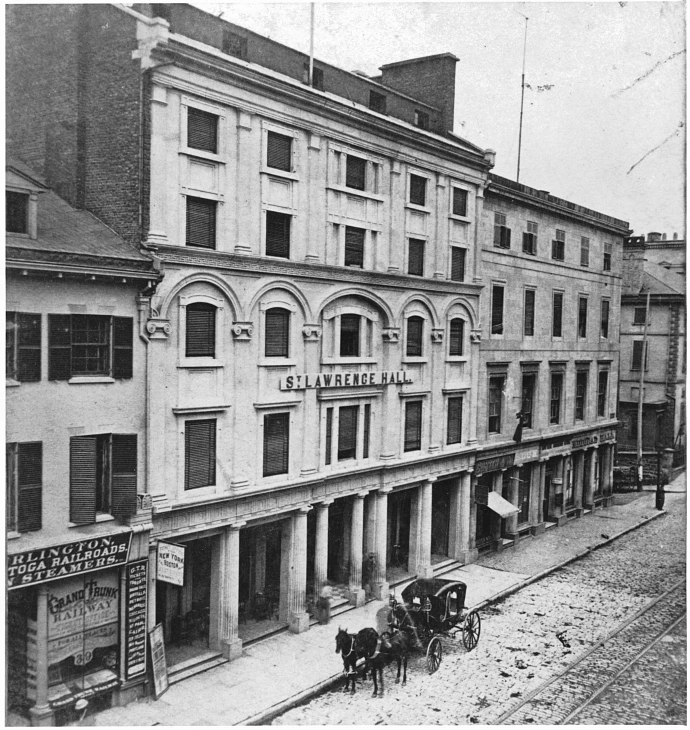

Let’s start with the character of George Sanders, who is introduced in this episode as a well-connected agent of the Confederacy. After arriving in Montreal on the secret orders given by Col. Lafayette Baker in the previous episode, Sandford Conover meets with Sanders, looking to collect the reward on John Surratt and John Wilkes Booth’s heads. The immensely wealthy Sanders is humored by Conover’s desire for such a paltry sum of several thousands of dollars. Still, he playfully betrays Surratt by offering Conover a coded hint, which, of course, only the efforts of our hero Stanton back in D.C. can solve. When Stanton arrives in Montreal looking for Conover and Surratt, he runs into Sanders outside the St. Lawrence Hall hotel. Sanders’ role as a pro-Confederate activist is established by the exposition provided by Stanton in this scene, and Sanders demonstrates that he now has the ear of President Johnson. The scene ends with Sanders informing Stanton that he has just bought the Manhattan Weekly and that big news will be coming tomorrow. The next day, the front page of the fictitious newspaper contains an editorial cartoon of Booth apparently being tempted by Stanton in the form of the devil. In the closing scenes, Sanders menacingly declares to a room full of Confederate supporters that he will protect all of those who had led the Confederacy.

While the real George Sanders was conniving and worked on behalf of the Confederacy, he wasn’t quite the Lex Luthor to Edwin Stanton’s Superman as portrayed in the show. He never had Union War contracts, attempted to convince Manhattan to secede, or bought a Northern paper as claimed in this episode. During the War, Sanders acted more as an unofficial diplomat for the Confederacy in Europe, hoping to gain approval and support from foreign governments. In addition, he endorsed and supported the efforts of Copperheads and the Democratic Party to get a peace candidate elected as President over Lincoln in 1864. Such an outcome would have been very favorable to the South and would likely have prevented the country from ever coming back together. Luckily, the battlefield successes of General Sherman in Atlanta in mid-1864 helped propel Lincoln to reelection.

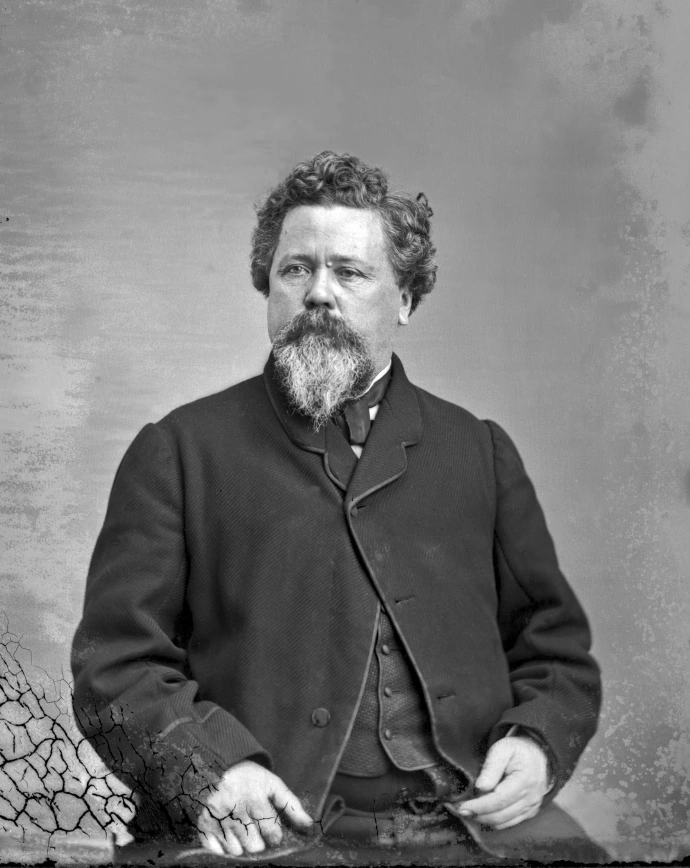

George Sanders’ real connection to our story actually takes place in October of 1864, when John Wilkes Booth visited Montreal in the early days of his abduction plot. Witnesses at the conspiracy trial testified that they had seen Booth in conversation with Sanders during the assassin’s 10-day visit to the city. Sanders was known for his radical ideas and had advocated for the “theory of the dagger” (i.e., assassinations) as a means of political change, especially when dealing with a tyrant. He had learned these radical ideas in the 1850s when he was living in Europe and rubbing elbows with revolutionary forces. Several authors have suggested that, during their meetings together in Montreal in October of 1864, Sanders may have influenced Booth’s plot.

The issue is that out of the six witnesses who testified as seeing Sanders and Booth together in 1864, half were later conclusively proven to have been perjurers (including Sandford Conover). Out of the three left, one was later convicted of his own fraud, though not in connection to his testimony regarding Booth. So the sightings of Booth and Sanders together are less than conclusive. In addition, we know that Sanders’ attention was very much occupied with other matters during the time Booth visited Canada. On October 19, the day after Booth arrived in Montreal, a group of Confederate guerillas dressed in civilian clothing enacted a raid on St. Albans, Vermont, robbing three banks before escaping into Canada. While arrested by the Canadian authorities, efforts by Confederate agents in Canada provided official commissions for the raiders, “proving” they were official Confederate soldiers. Due to Canada’s neutral stance in the ongoing American Civil War, the raiders were eventually released rather than being extradited, much to the anger of the Union. On October 23, Sanders left Montreal for Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec, where some of the raiders were held at that time. It wasn’t until three days later that he returned, and Booth left Montreal on October 27. So, while it’s possible that Sanders could have met with Booth, during this time the Confederate agent was pretty busy dealing with the aftermath of the St. Albans Raid.

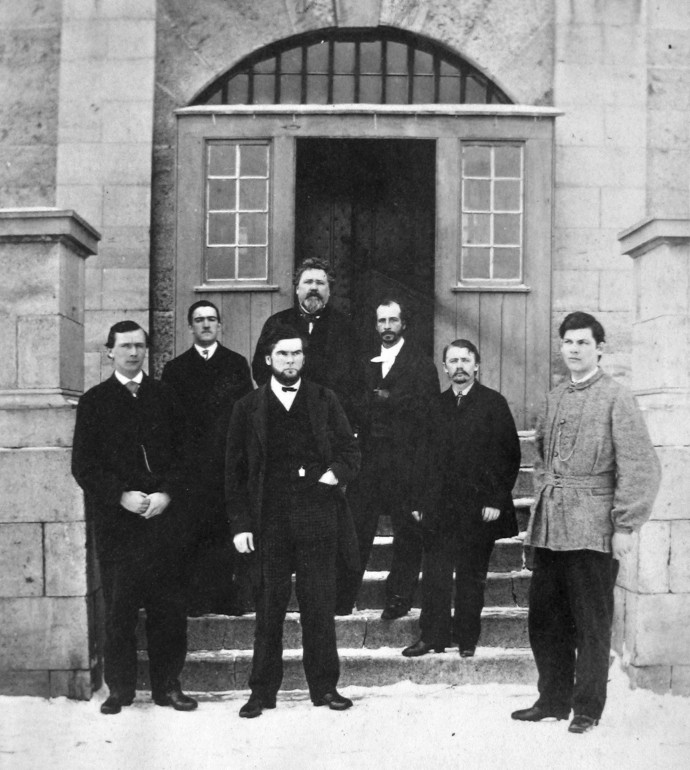

George Sanders (back row) pictured with some of the St. Albans Raiders outside their prison in Montreal.

I suppose there’s nothing wrong with making Sanders the embodiment of the big, bad Confederacy for the sake of this series. After all, aside from Patrick Charles Martin, Sanders is the only “big wig Confederate type person” where some evidence exists that he may have actually met Booth. Though he was never officially a member of the Confederate government, he had his hands in several actions that were important to the Southern cause. I fully expect Sanders’ possible connection with Booth to be portrayed in the next episode, which has the descriptor “Stanton and Detective Baker investigate ties between Manhattan’s most elite Wall Street traders, the Confederacy, and Booth.”

One of the more egregious fictions in this episode, however, is the idea that Sanders was in contact with President Johnson and that they had come to an agreement. While there is a lot of deserved shade to be thrown at the 17th President, the idea that he was in active communications with agents of the Confederacy in the aftermath of Lincoln’s death is preposterous. There was no “agreement” made between Sanders and Johnson regarding anything. On the contrary, when northern papers started accusing Sanders and others in Canada of possible involvement in Lincoln’s death, they countered by noting publicly that Andrew Johnson was the only person “who could possibly realize any interest or benefit from the perpetration of this deed.” Johnson hated Sanders and his ilk of Confederate agents.

The scenes regarding amnesty or pardons for Confederates are misrepresented here as well. The series is trying to put such acts in a nefarious light, as though Johnson is selling out the country. The series never mentions that Lincoln himself had issued earlier amnesty proclamations during the war and softens Lincoln’s countering of Stanton’s aggressive retribution for the South with his own “let ’em up easy” approach to Reconstruction. I understand the impulse to paint Johnson as being too lenient with the defeated South, but it is very much exaggerated this early in his Presidency. Johnson wasn’t looking for “wins” in his first month in office. He, like everyone else, was looking for revenge for Lincoln’s death.

4. The Escape of John Surratt

We already know that the events in these episodes are not occurring concurrently but are taking place at different times and dates. Most of Booth’s movements in this episode are things he and Herold did on the night of April 15/16. In the Washington portion of this episode, Stanton’s doctor remarks that it hasn’t even been a week since Lincoln’s death. In order to tell a more easy-to-follow and compelling story, I understand the need to alter the timeline of events. However, the series’ depiction of John Surratt’s time and then escape from Canada bears very little resemblance to the actual timeline or even the actual facts of the events.

After Stanton is able to solve Sanders’ clue that “Agent Surratt is here in Montreal to visit his father,” Sandford Conover makes contact with John Surratt who is in a Catholic monastery of sorts dressed as a fellow priest. Conover tells Surratt he is there to help him escape because Stanton is on his trail. While Surratt packs, Conover slips up the means of Surratt’s intended departure, revealing himself to be not friend but foe. Surratt grapples with Conover, knocks him unconscious, and ties him to a chair. Meanwhile, in Washington, Stanton has received a communique (assumedly from Conover) that Surratt has been located. Despite the protestations of his wife to take his health seriously and not travel, Stanton tells his servant to book him a room in Montreal. We are only left to guess how that servant in D.C. was expected to communicate with a hotel in Montreal to make such arrangements. Perhaps Stanton had access to the telephone or the internet long before either was invented. Luckily for the tied-up Conover, there is an extremely fast overnight train from D.C. that gets Stanton all the way to Montreal. The Secretary releases Conover, and the pair try to catch up with Surratt before he escapes via ship.

Unfortunately for the men, Surratt has escaped by sabotaging and sinking the ship he was traveling on and then swimming to a nearby Confederate vessel that whisked him away. Stanton is angry with the U.S. Navy officers who allowed Surratt to escape. They inform him that they found something interesting among the wreckage of the ship Surratt sunk. Stanton is shown a trunk that Conover confirms was in Surratt’s room at the monastery. It bears the initials JWB and is filled with Booth’s theatrical costumes. The naval officers also state that Booth’s name was on the manifest for the ship. Stanton then makes the conclusion that Surratt was traveling under Booth’s name with his trunk in order to sink the ship and fake the assassin’s death.

I was flabbergasted watching this entire portion of the episode. The whole sequence of events was complete fantasy and not at all grounded in reality. It was a storyline you’d expect to find in a piece of historical fiction “inspired” by the assassination, not in a series that takes its name from a largely well-respected nonfiction book on the subject. This time, the bones of the truth have not only been put in the wrong places, but the entire sculpture is completely unrecognizable.

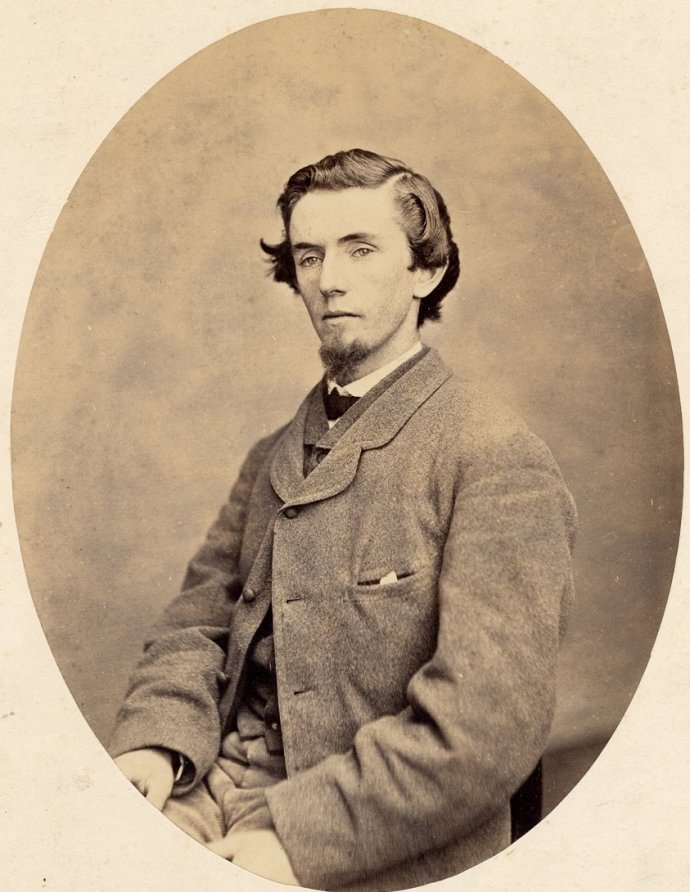

On the night of Lincoln’s assassination, John Surratt was not in D.C. nor in Southern Maryland. He was in Elmira, New York, on a prospective scouting mission of a Union prison holding Confederate soldiers. While the writing was on the wall for the end of the Confederacy, not everyone was ready to accept defeat. A hair-brained scheme was hatched by General Edwin Lee, a cousin of Robert E. Lee and a Confederate agent in Canada, to attack and free the imprisoned Confederates. Surratt had been sent to Elmira to gather information and then report back. When Surratt learned that Lincoln had been killed and that Booth had done it, he realized that his earlier connection with Booth’s kidnapping plot would incriminate him. He traveled from Elmira to Canandaigua, NY, a town about seventy miles north. He was stuck in Canandaigua for Easter, April 16, as no trains were running. On the morning of April 17, the danger Surratt was in became even more acute when the newspapers erroneously reported that he had been the man who attacked Secretary of State William Seward. Rather than escaping right into Canada by way of Niagara Falls, Surratt traveled east to Albany and then north to Whitehall, NY. From there, he boarded a steamer that sailed north on Lake Champlain, which separates New York from Vermont. He got off in Burlington, VT, and then took a train to St. Albans and thence into Canada. By midday on April 18, John Surratt was in Montreal and checked in at the St. Lawrence Hall hotel under the name “John Harrison.”

Surratt did not stay at the St. Lawrence Hall for long. It was known to be a hotbed for Confederate agents, and when Louis Weichmann arrived in Montreal with detectives on April 20, they headed straight there to consult the hotel register. Luckily, with the assistance of General Lee, who knew Surratt had not been in Washington at the time of the crime, Surratt was able to find people willing to hide him. His first benefactor was John Porterfield, a Nashville Banker with a stately home in Montreal. But Porterfield was well known for his Confederate ties, so it was determined that it would be too dangerous for Surratt to stay there long. He was then secreted by John Reeves, a working-class Canadian tailor whose Confederate sympathies were not so well known. All the while, Montreal was becoming too hot as Weichmann and his detectives kept on Surratt’s trail, and news of the reward for Surratt spread. It was decided that Surratt had to be moved out of the city into someplace safer.

On April 22, between five and six o’clock in the morning, Surratt was disguised as a huntsman and carried out of the city. He was transported to Saint-Liboire, a small parish in rural Quebec about fifty miles east of Montreal. It is here that Surratt was officially hidden by members of the Catholic faith. Surratt was introduced to the parish priest at Saint-Liboire as Charley Armstrong, an American recovering from the war. Father Charles Boucher invited the man into his home with open arms and tended to “Armstrong” who was quite feverish and weak at the time. Within about ten days, Father Boucher came to suspect that the man he was caring for might be John Surratt, who was wanted in connection with Lincoln’s assassination. When the father asked “Armstrong” if he was Surratt, the fugitive admitted it and told the priest his story. Later, at John Surratt’s trial in 1867, when Father Boucher was asked why he did not turn Surratt in, the priest replied, “Because I believed him innocent.” Surratt remained with Father Boucher in the still-isolated parish of Saint-Liboire for the next three months.

John Surratt later claimed to be completely ignorant of the trouble that befell his mother in D.C. He claimed that the men who cared for him only gave him sparse updates on the events in Washington and severely downplayed the danger his mother was in. Whether this was true or Surratt’s own later attempts to justify his lack of action on behalf of his own mother, we’ll never know. Surratt was hiding in Saint-Liboire during the entirety of his mother’s trial and execution.

Near the end of July, a servant girl caught sight of Father Boucher’s secret houseguest, and Surratt was moved from Saint-Liboire as a precaution. The manhunt had cooled considerably over the past three months, especially after Booth’s death and the trial of the conspirators. Surratt was moved to the resort town of Murray Bay (known today as La Malbaie), Quebec, about two hundred miles northeast of Saint-Liboire. Surratt enjoyed the fresh air and open water of the St. Lawrence River for a few weeks before being moved back to Montreal. Returned to the city he started in four months earlier, this time Surratt was hidden in the home of a shoe dealer whose son was a Catholic priest, Father Lapierre. From his second-story windowed room, Surratt had a view of the garden of the Bishop’s Palace, but he was not out and about clipping roses in priestly garb.

After being hidden away for the past four months, Surratt was feeling helpless and too close to the country that would never stop looking for him. He desired to seek asylum somewhere across the ocean. After receiving so much help from members of the Catholic clergy during his time in Canada, Surratt suggested to General Lee that he might find sanctuary at the Vatican as a member of the Papal Zouves, the Pope’s own army. The plan was approved and Lee was probably grateful that Surratt had suggested a course of action that would remove him from under Lee’s care and patronage. On the evening of September 15, a carriage arrived at the home where Surratt had been hiding out since his return to Montreal in August. Father Boucher and Father Lapierre were there to help Surratt during this last part of his escape through Canada. Surratt disguised himself by dying his hair dark brown and wearing a pair of glasses. The three men took a steamship from Montreal to Quebec City where transatlantic ships departed from. Fathers Boucher and Lapierre bid farewell to Surratt as he boarded the steamer Peruvian on the morning of September 16. At about 10:30 that morning, the Peruvian steamed away from Quebec City on its way to Europe. John Surratt had successfully escaped out of Canada just about five months after he had arrived.

As you can see, Surratt was not betrayed by George Sanders or any other Confederate. It was Weichmann and detectives who searched for Surratt in Montreal, not Conover and Stanton. There were no close calls that resulted in Surratt laying down the fisticuffs. Rather than getting in and out of Canada in the week after Lincoln’s death, it took five months to get Surratt out of the country. He spent most of his time hiding out in a rural Quebec parish, not in the bustling city of Montreal. And, most laughably of all, Surratt did not travel under Booth’s name, nor did he sink an entire ship in order to fake Booth’s death.

Quick Thoughts

Here are some more things that stood out to me while watching episode 3 that I just don’t have the time to go into deeply.

- Just a friendly reminder that Sandford Conover was a perjurer and a fraud who didn’t show up on the scene until the time of the Lincoln conspirators’ trial. All of his scenes in this series so far are fictional.

- Somehow, Stanton and the press know Lewis Powell’s real name from the beginning. But, there’s a reason why Betty Ownsbey named her biography on Powell Alias “Paine”: Lewis Thornton Powell, the Mystery Man of the Lincoln Conspiracy. In reality, Powell used a number of aliases. Even his fellow conspirators only knew him as “Mosby” or “Paine.” The government didn’t know his real name until long after the conspiracy trial had begun when he finally divulged his real identity to his defense attorney.

- A hood is aggressively placed on Powell’s head when Stanton interrogates him about Sanders’ clue about Surratt. The implication is that the hood was a torture device. While the conspirators who wore them probably considered them torturous, they were not used in such a way purposefully. The reason for the hoods was to prevent the conspirators from communicating with each other during their imprisonment.

- There are so many anachronistic terms in this series. Phrases like “double agent,” “stuntman,” “laundering money,” and others really pull you out of the period piece.

- Related to the last point, Stanton calls practically everyone by their first names or nicknames. William Seward is “Bill,” Andrew Johnson is “Andy,” and Joseph Holt is “Joe.” I suppose those nicknames are acceptable, but Stanton constantly calls Lincoln “Abe,” a nickname the President never liked very much. I also don’t like how Stanton addresses women by their first names, like Mary instead of Mrs. Lincoln or Elizabeth instead of Mrs. Keckley. Victorian rules of etiquette would not have allowed Stanton to be so casual with women such as the First Lady or her Black seamstress.

- Booth is still on about Richmond even after somebody finally told him that there is no Confederate leadership or adoring fans for him there. The real Booth was quite aware that Richmond had fallen and was occupied by the Union. He never would have wanted to go there.

- When Davy asks Oswell Swann why he doesn’t turn them in for the money, he replies that a Black man like himself would never be awarded reward money. While it’s true that the real Swann did not get a share of the reward, Susan Jackson, a Black servant at Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse, did receive $500 in reward money for information she gave about visitors to the Surratt home.

- “River Ghost” is not a period name for Thomas Jones. I’m pretty sure this is a descriptor Swanson made up for him in his book. It sounds all mysterious but it’s pretty silly to have Cox make statements such as “You don’t find the River Ghost. He finds you,” when, in reality, he sent his son over to Jones’s house to fetch him. When Jones came to Rich Hill as requested, Cox told his foster brother about Booth and Herold. Not to mention the River Ghost in this series looks more like Hagrid from Harry Potter rather than the scrawny Thomas Jones.

- You gotta love the code phrase for the Confederate cipher being taped to the bottom of the cipher cylinder itself. Good to know the Confederacy has the same security mindset as a grandmother who keeps all her computer passwords written on a Post-It-Note stuck to the front of her computer monitor.

- Speaking of the cipher, the super secret message that Eckert is finally able to decode is the phrase “Come Retribution.” This was actually the code phrase that replaced “Complete Victory” in Confederate ciphers starting in the final months of the war.

- Just to reiterate, the “Confederate cipher” found in Booth’s room is just a repeating grid of the alphabet. There were no actually coded letters found in Booth’s things. Click here to read an old post of mine about this nothing-burger of evidence.

- Trunks of Booth’s theatrical costumes and promptbooks were actually recovered from a shipwreck, but they had nothing to do with John Surratt or Booth faking his death. During Booth’s visit to Montreal in October of 1864, he met Patrick Charles Martin, a Baltimore liquor dealer turned Confederate smuggler. Martin is the man who gave Booth a letter of introduction to Dr. Queen in Charles County, which brought Booth into Southern Maryland for the first time. Martin was planning on running the Union blockade and traveling into the Confederacy. Having grandiose dreams of abducting Lincoln and taking him to Richmond, Booth wanted his theatrical wardrobe to be in the South for his future life there. He arranged for Martin to take his trunks of costumes on his ship bound for the Confederacy. However, Martin’s schooner, Marie Victoria, floundered in a storm and sunk two weeks later in the St. Lawrence River. All hands, including Martin, were lost. In late May of 1865, salvage operations were underway to recover some of Marie Victoria‘s cargo. When trunks belonging to John Wilkes Booth were discovered among the wreckage, they were transferred over the the U.S. consulate in Canada. Containing no secrets, the trunks were later auctioned off in admiralty court. Eventually, Edwin Booth managed to acquire his brother’s trunks from a third party. He kept John’s costumes and play books until a fire gutted the Winter Garden Theatre and destroyed them in 1867.

Patrick C. Martin, the man who drowned attempting to smuggle Booth’s theatrical trunks out of Canada in 1864.

- I’m not sure the Canadian government would have allowed the U.S. Navy to operate on their soil or impede their trade in 1865.

- When Booth and Herold are in the pine thicket waiting to meet the “River Ghost,” Davy complains about the cold and begs Booth to let him light a fire even if the smoke may attract attention. This is correct logic and why the fugitives did not have campfires during their stay in the pines. But the smoke was not the only thing that might draw attention. The light of the fire could easily be spotted at night. Yet, here the pair sit with a bright lantern in the woods, drawing attention to themselves. Where did they get the lantern anyway? They certainly didn’t have it when Swann dropped them off, and Thomas Jones only makes his first appearance later in this scene. I feel like there are other ways to shoot night scenes that wouldn’t require the actors to have artificial illumination.

- Davy is unable to shoot his horse when instructed to by Booth. Instead he fires into the air, scaring the horse and sending it galloping off. This failure leads Booth to comment that Davy is “Useless. F*cking, useless.” I enjoyed the humor of this series taking Booth’s supposed final words (minus the expletive) and attributing them to his disappointment at Davy. However, much like Davy’s aim, this horse-shooting scene is way off the mark. While the horses did make too much noise in the pine thicket and had to be dispensed with, Booth did not take part in the proceedings. Instead, our best evidence states that David Herold was helped in this task by Franklin Robey, the overseer of Samuel Cox’s farm who escorted the men to the pine thicket. The pair took the horse a good distance away from the pine thicket and into the nearby Zekiah Swamp. After leading the horses into the swamp Herold and Robey shot them both and sunk their bodies where they would not be found. Then Herold rejoined Booth in the pine thicket. One wonders if the decision Will Harrison’s Davy makes to let a horse escape will come back to bite the pair.

- After shooting the horse, Booth tells Herold that his mother hired a soothsayer to predict his future. The mystic told the family that Booth would become a hero but would die young. While this is a very basic and slightly inaccurate summary of a true enough story. When Booth was 13, he attended Milton Boarding School near Cockeysville, Maryland. At around that time, a group of English gypsies were reported to be in the woods not far from the school. On his own, Booth sought out the fortune tellers to learn something of his future. A few days later, when his mother and sisters came to see him perform in a play for the closing of the school year, Booth pulled his sister Asia aside and showed her the fortune the gypsy had told him. He had written down what she said after the fact. The gypsy had said:

Ah, you’ve a bad hand; the lines all cris-cras. It’s full length enough of sorrow. Full of trouble. Trouble in plenty, everywhere I look. You’ll break hearts, they’ll be nothing to you. You’ll die young, and leave many to mourn you, many to love you too, but you’ll be rich, generous, and free with your money. You’re born under an unlucky star. You’ve got in your hand a thundering crowd of enemies—not one friend—you’ll make a bad end, and have plenty to love you afterwards. You’ll have a fast life—short, but grand one. Now young sir, I’ve never seen a worse hand, and I wish I hadn’t seen it, but every word I’ve told is true by the signs. You’d best turn a missionary or a priest and try to escape it.

Nothing in the gypsy’s prediction mentioned Booth becoming a hero, but I suppose it would be in Booth’s character to interpret this story in the best way possible.

Those are my thoughts on the third episode of Manhunt, Let the Sheep Flee. We will have to wait and see if the series will continue to diverge even farther from the historical record. During my first watch-through I was angry at all the changes that were made. I know that some of these changes make the story more exciting, but the perfectionist in me still hates to see so many alterations to the truth, especially when some don’t seem to serve much of a purpose other than to add drama and intrigue. It wasn’t until my second watch-through that I was able to chill out a bit and resign myself to the fact that, like the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, this series is just an impressive piece of fiction.

My review of the upcoming fourth episode will likely be delayed until after episode 5 airs. I have been devoting way too much time to these write-ups, and there are things coming up in my life that have to take precedence, including my actual job and a private speech I am giving soon about the real escape and manhunt for Booth. In addition, the great solar eclipse is going to be occurring right over my backyard in less than two weeks and I have family coming to stay with us during that time. I appreciate your patience as there is a bit of a lull in my historical reviews of this series.

Until next time,

Dave aka “The Bone Collector”

Hello Dave……and followers……..I am going to try and make this a short post……I’ve been dealing with a lingering illness and am just now getting over the hump……the first thing I want to mention is that I ‘have no horse in this race”…..I have been a fan of Dan’s work and passion from the earliest days of “Boothie Barn”……..I am simply a history lover with a specific passion for Abraham Lincoln and his life and times…..to put it in “perspective” , I have a bit of an obsession in this regard…(though my wife tends to use other words for it)…I have read over 600 books on Lincoln ,his life and death , and many connected subjects….I have a small museum in my home…and a not-so-small one in my backyard shed…so….maybe a little obsessive……I have been waiting for “Manhunt ” the series since Dave brought it to my attention here…I have read the book 5 times……and ……after it’s debut , debated if I wanted to post on here…….my lack of energy held me back…….but…..at this point I want to put my 2 cents in; this in my humble opinion is INCOMPREHENSIBLY bad……..shockingly disappointing……..while I 100% understand and support artistic license , this goes beyond anything acceptable never the less laudable……twisting history from it’s very roots of truth just simply not progress and not what needs to be taught or in any way credited with encouraging historical research (and love of the same)……..they have taken the most fascinating, dramatic , mind-blowing time and story in American , if not all , of history, and made it into a pathetic attempt at not historical fiction but historical “pulp fiction”……..I’m not sure how any true fan of history…of Lincoln and this story…..of history ……and of this terrific website , can see otherwise……..anyhow…so much for a short post…….but…I felt an obligation….Dave, hope you are well…..thanks for the continuing great contribution to history and this subject…….and now….I really , truly need sleep………thanks……

very interesting to learn what you have to say about the historical facts. I bet your description of the CSA spy and terrorist network as often uncoordinated operations fits best with the known facts. Whatever Booth did with his time in Montreal there seems to me a plausible case that he was coordinating his abduction/ assassination scheme with the Montreal command. Sanford’s role in everything always seems unclear, and the tv drama, I agree, adds a whole layer of fiction that further muddies the water. The role of the Catholic priesthood in sustaining the Surratt family and harboring John Surratt and sending him to Rome and, possibly, helping him escape Rome, something I had hoped the tv show would illuminate. I’m on episode 3 so maybe they will get there.

I share your exasperation with writers who distort the history often unnecessarily, especially when the truth would serve them better.

I still find the series riveting and love Toby M’s Stanton.

thanks for your posts. I look forward to more.

—Don Doyle

Manhunt has already introduced us to Col. Lafayette Baker and his right-hand man and first-cousin, Luther Byron Baker, as two of the chief hunters. They were in New York City when a telegram from Sec. Stanton on April 15th told them of the attack on the president and ordered them to return to Washington City. In the second program of Manhunt Colonel Baker says he will bring a unit of cavalry with them. He then says to Byron, “You, dear Cousin, are my eyes and ears inside the 16th New York Cavalry.”

The Sixteenth New York Volunteer Cavalry played a pivotal role in the pursuit of the assassins, but not in the way Manhunt has already suggested. First off, the 16th was not in the north, they were in Virginia when they heard via telegraph at dawn on Saturday morning. The regiment had joined the search for the conspirators before the Baker cousins had even left Manhattan. The regiment was stationed at the stockade at Ayr Hill in Vienna, VA, their usual duty station where they served as a screen to protect the southwest approaches to Washington. They and their sister regiments, the 8th Illinois Cavalry and the 13th N.Y. Cavalry, formed a long skirmish line that swept Northern Fairfax county, starting early on the 15th. The following day, the time when the Bakers arrived back in DC, about half of the 16th “took the cars” for Washington in preparation to form an escort for the funeral for the late president.

The Sixteenth was often back in Washington City, in fact. They were present for the Second Inauguration, and members took part in many public and private events. It seems probable, for instance, that one of the troopers of the regiment – who later took part in the capture of Booth at Garrett’s Farm—was in the audience at Ford’s when Booth killed the president.

They were housed at the Lincoln Barracks across from Lafayette Square and the President’s House. Squads were sent in various directions during the army hunt for Booth and his co-plotters. Boston Corbett later reported that he was a member of a small patrol led by Lieut. Edward Doherty which was sent into Maryland in company with several detectives. They had just ridden in the State funeral parade and received orders before they had even returned to their barracks.

The 16th provided street security in Washington, did crowd control at the time of the Grand Review of the Armies and were on duty at the Arsenal Penitentiary. Cavalrymen were stationed at intervals between the Executive Mansion and the penitentiary on the morning of the hanging in the event that President Johnson would pardon any of the prisoners and a fast horse would bring a last minute reprieve.

The first time that any members of the unit were placed under direct orders of Col. Baker was the when the Doherty patrol was ordered to go via steamer down into Virginia starting on April 24th.

Ugh! I thought it couldn’t get worse than Episode 3…then I saw Episode 4. What utterly laughable dreck! Too much to comment on…Mudd using the modern phrase “hunky-dorey”…all the Montreal stuff…Lafayette Baker’s line “You mess with New York City you mess with me”….Mary Lincoln and Stanton with Edwin Booth in the aftermath… It’s not just the rewriting of history…it’s just plain bad! As always, Dave, I’m enjoying your commentary tremendously.

It would be considerate if you took the time to do a ten second search before making such claims. Hunky-dorey is period correct. “The informal hunky-dory is perfect for those times when everything is great, going according to plan, or not bad at all. This American-coined adjective has been around since the 1860s, from the now-obsolete hunkey, “all right,” which stems from the New York slang hunk, “in a safe position,” and the Dutch root honk or “home.” The origin of dory is unknown.“

Also, wit existed in 1865….

I guess you prefer Mary Lincoln exited the show after the assassination. Maybe stick to Ken Burns if this bothers you so much? Some of us are having a blast and the showmakers bringing millions of people to the research you’re so invested in and interested in is more impactful than a literal history lesson.

Dorothy, I’m not the person you replied to and I can only speak for myself – and I have no comment on the usage of “hunky-dory.” I do disagree with you on the latter portion of your response.

The TV show doesn’t have to be a literal history lesson with every single detail perfect. But major plot points are completely fictional and it’s giving people the wrong idea about what happened. I would rather have people taught nothing than taught something that is false. Will the average reader come away from the first four episodes knowing that there actually was no evidence linking the Confederate government to the assassination, that Surratt did not make the miraculous escape ascribed to him, or that President Johnson wasn’t under the thumb of the Confederacy from day one in office (for instance)? Or will they presume those things are true?

I don’t see how it helps the situation that now a number of people are probably going to fundamentally misinformed about it, when beforehand they simply did not know the details. Is the former really better?

I just recently stumbled upon this website and wanted to voice my appreciation of it and the reviews of the recent Apple TV+ interpretation of Manhunt. Like many who read the book, I was looking forward to the adaptation (but also not holding out very much hope that it would do the book justice, even with Swanson as an E.P.).

While I understand the need for creative license when adapting a book to television, as someone who was riveted by Swanson’s account and was inspired by it to do further research into the Lincoln assassination, it is disappointing to see just how far the show has deviated from the book (and from the historical record, as I understand it).

The show may well have its merits, and if nothing else, should help to bring to light details about the assassination that many of us never learned in school. But my feeling is that the real-life events as I understand them are far more interesting than what we are seeing in the show, and I think a person interested in learning about them would be well advised to stick with the book and maybe skip the TV show.

Regards,

Dave

The one thing about the fiction of the show that disturbs me is the portrayal of Johnson. One would think that Johnson intended to bring back slavery and restore the ante bellum South. Johnson was a bad president and her certainly later on clashed with Stanton and other “Radical Republicans” but he was fiercely loyal to the Union (the only member of Congress from a state that seceded to stay loyal to the Union) and I think he tried to carry out what he thought (rightly) as Lincoln’s liberal policy of reconstruction over the objections of Stanton and others. This series almost makes him seem like a confederate loyalist.