In an earlier post, I introduced you to Carrie Bean, a young socialite from New York who journalist George Alfred Townsend claimed had breakfast with John Wilkes Booth on the morning of Lincoln’s murder. GATH is our only source for this event, but Miss Bean’s connection to the National Hotel and some of its residents makes it possible that this breakfast did occur. However, Carrie Bean is not the only one who has been linked to the assassin’s morning meal. There are sources that state that Booth spent his final breakfast before his infamous deed in the presence of his fiancée, Lucy Hale.

Lucy Hale likely needs no introduction to readers of this blog. In 1865, Lucy was the 24-year-old daughter of New Hampshire Senator John P. Hale and his wife, Lucy Lambert. The Hales often resided at the National Hotel when staying in Washington. At the time of the assassination, Senator Hale was in a sort of limbo. In June of 1864, the statesman had lost his bid for renomination by the New Hampshire Republican party and was replaced by Aaron Cragin. When Lincoln took office for his second term on March 4, 1865, Hale was officially out of a job. However, the staunch abolitionist lobbied for an ambassadorship position. On March 10, Hale was nominated to become the administration’s new minister to Spain. At the time of the assassination, the Hales were preparing for their new lives abroad.

At what point John Wilkes Booth and Lucy Hale met and subsequently became romantically involved is unknown. A commonly repeated yet erroneous story claims their romance began in 1862 when Booth sent Lucy a valentine signed “A Stranger.” This is too early of a period for the two to have become entwined. John Wilkes Booth didn’t even make his first appearance on the D.C. stage until 1863. The source of this erroneous story is a letter to a “Miss Hale” that was found in an antique store by Richmond “Boo” Morcom. In 1970, American Heritage published an article written by Morcom titled, They All Loved Lucy, in which he attributed the letter to Booth without evidence. After Morcom’s passing in 2012, his papers were donated to the New Hampshire Historical Society. A look at the original document shows that the letter is not in John Wilkes Booth’s handwriting. To demonstrate this, here is the end of the “Stranger” valentine found by Morcom with a sample of John Wilkes Booth’s writing underneath it. I’ve underlined some of the same words found in each letter for easy comparison.

The letter and word formations are just too different to have been written by John Wilkes Booth.

The letter and word formations are just too different to have been written by John Wilkes Booth.

Part of the reason this incorrect story continues to live on is due to the fact that John Wilkes Booth is known to have composed a valentine for Lucy Hale. Junius Brutus Booth, Jr. wrote a letter to his sister Asia, updating her on family matters. John Wilkes was visiting Junius in New York at the time and June wrote to Asia that:

“John sat up all Mondays night to put Miss Hales valentine in the mail – and slept on the sofa – to be up early & kept me up last night until 3 1/2 AM – to wait while he wrote her a long letter & kept me awake by every now and then useing me as a dictionary…”

While John Wilkes is documented as having composed a valentine for Lucy Hale, this occurred in February of 1865, and we do not have any idea what his valentine said. It was likely destroyed, along with all other correspondences from Booth, by Lucy Hale or her family in the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination.

While Lucy and Booth may have known of each other as early as 1863, when Booth made his Washington debut, it doesn’t seem like they had much in the way of a relationship until late 1864. During the summer and early fall months of 1864, John Wilkes Booth stayed with his family in New York and then traveled into the Pennsylvania oil region. He was actually infatuated with another woman at this time, 16-year-old Isabel Sumner, whom he had met during his Boston engagement in the spring. It wasn’t until November of 1864 that Booth’s residency at the National Hotel started as Washington became his base of operations in his conspiracy against Lincoln. Thus, his and Lucy’s romance was a relatively quick one.

A few years ago, I wrote about an envelope dated March 5, 1865, that contains poems by John Wilkes Booth and Lucy Hale. I explained that while some authors have used this envelope as evidence that the couple broke up on this date, I believe this conclusion to be incorrect. The two were planning a life together despite the difficulties involved with her father’s nomination to be the next minister to Spain. Lucy was expected to accompany her family to their new country. As a result, John P. Hale started having his family learn some of the Spanish language they would soon be immersed in. In mid to late March, Lucy Hale traveled to New York City and stayed with friends as she took some rudimentary Spanish lessons. On March 21, Booth traveled up to New York City ostensibly to be there for his brother Edwin’s 100th night of Hamlet the next day. However, according to Junius Brutus Booth, Jr.’s diary entry on March 22, “John came on to see Miss Hale.”

In the aftermath of John’s crime, Asia Booth wrote a letter to her friend Jean Anderson where she described the relationship between John and Lucy as the Booth family understood it:

“I told you, I believe, that Wilkes was engaged to Miss Hale. They were devoted lovers and she has written heart-broken letters to Edwin about it. Their marriage was to have been in a year, when she promised to return from Spain for him, either with her father or without him. That was the decision only a few days before this awful calamity. Some terrible oath hurried him to this wretched end. God help him.”

There is no evidence that Lucy Hale had any foreknowledge of what her secret fiance was planning.

Due to her being the daughter of a former Senator, Lucy Hale’s name was mainly kept out of the papers in the aftermath of Booth’s crime. There were a few references to Booth having been engaged to a New England Senator’s daughter, but propriety kept her actual name out of it. As years went by, however, more details came out about their relationship from some of Booth’s former friends and acquaintances.

In December of 1881, a journalist by the name of Col. Frank A. Burr wrote at length about John Wilkes Booth for the Philadelphia Sunday Press. Burr had done an immense amount of research into the life and death of John Wilkes Booth. He traveled down to the Garrett Farm and interviewed members of the Garrett family about Booth’s final days. He visited Green Mount Cemetery and described the Booth family plot. Burr also interviewed friends of Booth’s in order to flesh out his motivations. The result was one, or perhaps two, lengthy articles covering many aspects of Booth’s life, crime, and death. The reason I am uncertain about how many articles Burr’s work was split into is because, try as I might, I have been unable to track down the relevant Sunday issue(s) of the Philadelphia Press. These particular editions seem to be an endangered (or possibly extinct) species in archives and libraries today.

While Burr’s original piece has proven elusive, continued interest in Lincoln’s assassination meant that several newspapers reprinted parts of his work, often splitting it up into more manageable portions. The Evening Star out of Washington, D.C., appears to be one of the first to reprint part of Burr’s work. A lengthy article called “Booth’s Bullet” credited to the Philadelphia Press and “F.A.B.” was published in the Evening Star on December 7, 1881.

It appears that the Evening Star chose to cut out the whole section about Burr’s trip to the Garrett farm. Instead, the article was broken into three sections. The first section documented Burr’s visit to John Wilkes Booth’s grave in Green Mount Cemetery. The second was an interview Burr had with John T. Ford, and the third section was Burr’s interview with actor John Mathews. On the day of the assassination, Booth had given Mathews a sealed envelope, which he instructed Mathews to give to the newspapers the next day. The envelope contained Booth’s written explanation for why he assassinated Lincoln. Mathews was a member of the Ford’s Theatre cast and witnessed Lincoln’s assassination firsthand. Afterward, he returned to his boarding house, which happened to be the Petersen House, where Lincoln was taken. As the President lay dying in an adjacent bedroom, John Mathews opened the sealed envelope and read the assassin’s manifesto. After finishing it, Mathews made the decision to burn the letter, fearing it would implicate him in Booth’s great crime. The entirety of the “Booth’s Bullet” from the Evening Star can be read here.

Within this article, there are several references to Lucy Hale. John T. Ford stated to Burr that:

“Booth was a very gifted young man, and was a great favorite in society in Washington. He was engaged, it was said, to a young lady of high position and character. I understood that she wrote to Edwin Booth after the assassination telling him that she was his brother’s betrothed, and would marry him, even at the foot of the scaffold.”

John Mathews related a lengthy exchange he had with Booth regarding love and Lucy Hale:

“‘John, were you ever in love?’

‘No. I never could afford it.’ I replied.

‘I wish I could say as much. I am a captive. You cannot understand how I feel. What are those lines in Romeo and Juliet describing love? I have played them a hundred times but they have flown from me.’

‘Will you stand a bottle if I’ll give them to you?’ I asked.

‘I will – two of them,’ replied Booth.

‘Here are the lines,’ I answered:

O! anything, of nothing first create!

O! heavy lightness! Serious vanity!

Mis-shapen chaos of well-seeming forms!

‘That’s it,’ replied Booth. ‘If it were not for this girl I could feel easy. Think of it, John, that at my time of life – just starting, as it were – I should be in love!’[Burr:] Did he mention the lady’s name?

[Mathews:] Oh, yes; but that shall be sacred with me. She is married now, and it would serve no good purpose either to his memory or to the truth of history to revive it. He loved her as few men love. He had a great mind and a generous heart, and both were centered upon this girl, whom he intended to make his wife. Her picture was taken from his person after he was killed.”

In addition to these mentions of Booth and Lucy’s romance, this article is the earliest source that places Lucy Hale with Booth at breakfast on the morning of his great crime. John T. Ford stated the following:

“The facts in the case are that he never knew the President was to attend the theater until nearly noon of that day. He was always a late riser. He came down to breakfast about ten o’clock on that morning, and his fiancee, who also boarded at the National Hotel with her parents, met him. They had a short conversation, and after breakfast he walked up to the Surratt mansion on H street, as is supposed from the direction in which he was first seen coming by the attaches of the theater that morning.”

To be fair, this description is a little vague as to whether Lucy Hale joined Booth for breakfast or merely had a conversation with him during his breakfast. Lucy’s inclusion is really a throwaway reference in a section about Booth’s movements. However, it still connects the two on the morning of the assassination.

Another paper that reprinted Frank A. Burr’s work was The Atlanta Constitution. They published the story of Burr’s visit to the Garrett farm on Sunday, December 11, 1881. A month later, on Sunday, January 15, 1882, the Constitution published another article attributed to Burr titled “Booth’s Romance”.

This article was similar to the earlier article found in the Evening Star, but “Booth’s Romance” is markedly different in spots from “Booth’s Bullet.” The section about visiting Booth’s grave is not present in the Constitution, and while the interviews with John T. Ford and John Mathews are present, they have been moved around, reworded, and elaborated on in different places.

For example, here is the beginning of “Booth’s Romance”:

“‘Oh! If it were not for that girl how clear the future would be to me! How easily could I grasp the ambition closest to my heart! With what a fixed and resolute purpose, beyond all resistance, could I do and dare anything to accomplish the release of the confederate prisoners! Thus reviving the drooping southern armies, and giving new heart to the waning cause!

What are those lines in Romeo and Juliet describing love? I have played them an hundred times, but they are now covered with the mist of greater thoughts and I cannot see them. I am, I am in love!’

‘O! any thing of nothing first create!

Oh! heavy lightness! serious vanity!

Mis-shapen chaos of well seeming forms!’

quoted an actor associate and friend into whose room John Wilkes Booth had strode one morning in April, 1865, and thrown himself upon the bed, his mind torn with conflicting emotions.”

In content, this introduction is similar to the exchange between Booth and John Mathews as written in “Booth’s Bullet,” but it is portrayed and narrated differently in “Booth’s Romance.” A similar change is present in the part about Booth’s breakfast. “Booth’s Romance” does not talk about Booth’s breakfast in the same section as John T. Ford’s interview but merely narrates Booth’s movements uncredited:

“About 10 o’clock in the morning of the day upon which the crime was committed Booth came down the steps of the hotel to the breakfast room, late as an actor’s wont. Immaculately dressed in a full suit of dark clothes, with tall silk hat, kid gloves and cane, he walked forth the young Adonis of the stage… At the foot of the stairs he met his fiancee, who was there awaiting his coming. They walked into the breakfast room, and took their morning meal together. A few minutes chat in the parlor followed. Those words were doubtless the last she ever spoke to him.”

In this version, Booth and Lucy Hale definitively shared breakfast together before they departed from each other’s company. However, there is no attribution for this added detail, and it appears to be an unsupported elaboration. “Booth’s Romance” is filled with confusing attributions when compared to “Booth’s Bullet”. For example, in the section cited as the interview with John T. Ford, we get this exchange:

“‘He was received by the very best people. The lady to whom he was engaged to be married belonged to the elite of Washington society.’

‘Do you know the lady’s name?’

‘Yes, but it shall be sacred. She is married now and it would do no good to the truth of history to revive it. Booth’s whole soul was centered upon her, and he loved her as few men love. Her picture, I understand, was taken from his body a short time after his capture, and she was faithful to him to the very last.'”

These statements are said to be from John T. Ford, but the ending part about Lucy Hale’s name being “sacred” was attributed to John Mathews in the article “Booth’s Bullet.” It appears the composer of “Booth’s Romance” combined the two statements by Ford and Mathews together and attributed them all to Ford. However, without access to Burr’s original work in the Philadelphia Press, it’s hard to know which account, if either, is the accurate portrayal.

Regardless, these articles from Frank Burr seem to provide John T. Ford as the source for the claim that John Wilkes Booth shared his breakfast with Lucy Hale on April 14, 1865. But how reliable is that story?

It’s important to remember that John T. Ford was not in Washington, D.C., on the day of the assassination. In truth, Ford was not all that involved with the day-to-day operations of his namesake theater. He had spent most of the winter and spring of 1864-1865 in Baltimore, running his Holliday Street Theatre. He left the management of Ford’s Theatre in the hands of his brothers, Harry and Dick Ford. When Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theatre, John T. Ford was in Richmond. Before the war, Ford had operated a theater in Richmond, and he still had family in the area. With the fall of the Confederate capital earlier that month, Ford had applied for and received a military pass to travel south. All of John Ford’s knowledge about the specifics of the assassination comes from what he learned from his brothers, employees, and eyewitnesses after his return to the city.

This isn’t to say that John T. Ford is someone we should ignore. While he wasn’t in town when Lincoln was shot, when he returned to Washington, Ford was arrested and held at the Old Capitol Prison. He wrote a great deal about his time in prison and his interactions with some of the other folks imprisoned with him. Ford became a big proponent of Mary Surratt’s innocence as a result of what he witnessed while incarcerated.

In April of 1889, John T. Ford published an article in the North American Review entitled, “Behind the Curtain of a Conspiracy”. If you want, you can read the full article here. The bulk of the piece was a defense of Mary Surratt and an attack on Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt for allowing Mrs. Surratt to be executed. However, Ford also took the time to narrate John Wilkes Booth’s movements on the morning of the assassination. When discussing Booth’s breakfast, John T. Ford wrote this:

“On the morning of April 14, 1865, it was fully 11 a.m. when John Wilkes Booth came from his chamber and entered the breakfast-room at the National Hotel, Washington. He was the last man at breakfast that day; one lady only was in the room, finishing her morning meal. She knew him and responded to his bow of recognition. He breakfasted leisurely, left the room when he had finished, went to the barber-shop…”

Ford makes no mention of Lucy Hale in this 1889 article. His allusion to a single lady in the breakfast room more closely matches GATH’s description of Carrie Bean from 1865.

The reality is that John T. Ford was extremely inconsistent when discussing Booth’s breakfast over the years. In an article from 1878, he stated that Booth, “was the last guest at breakfast” and makes no mention of any ladies being present. To Col. Burr in 1881, he stated that Lucy Hale met Booth at breakfast, but it is unclear if she joined him for the meal. Then, in 1889, he wrote that another unnamed lady was also eating breakfast at the time. John T. Ford is all over the map.

Perhaps the most interesting of all of John T. Ford’s descriptions of Booth’s breakfast is one that he gave to the Evening Star on April 18, 1885. In this account, Ford includes both Carrie Bean and Lucy Hale.

“The last male guest at the National hotel breakfast, on the morning of April 14th, 1865, was John Wilkes Booth. When he entered the breakfast room, a young lady, Miss B—. was finishing her meal at a small table near by the one assigned him by the waiter in charge. He glanced over the bill of fare and pleasantly whispered his order for a light meal, which was soon brought. The young lady lingered at her table. The young actor was an acquaintance, and a known admirer of one of her feminine friends – (the daughter of a distinguished public man, whose family occupied a suite of rooms at the same hotel,) besides he was young graceful, and exceedingly handsome. His breakfast was soon finished, he rose as the lady did, and they walked together to the door, where his silk hat, light overcoat, cane and gloves were lying on a table. He laid the coat on his left arm, and with hat, gloves and cane in his hands, he bowed to the young lady and passed along the hall way and down the steps to the office, placing his hat and coat on and leisurely gloving one hand, he noticed that it was after eleven by the hotel clock, as he sauntered towards the door on the Avenue. At this time two handsomely dressed young ladies were passing – he bowed, they acknowledged the salutation and entered the parlor hallway of the hotel. Had any one been looking on when he drew and opened an encased picture from a side pocket, the likeness of one of the two ladies would have been recognized in the subject of the ambrotype. He quickly replaced the picture in his pocket, and started in an easy loitering walk towards 6th street…”

Ford paints a compelling and almost theatrical scene in this article. Booth shares a meal in the same room as an acquaintance, Carrie Bean, who admires the matinee idol and delays completing her meal so that they will finish at the same time. Always the gentleman, Booth escorts Carrie Bean from the breakfast room and bids her adieu. Preparing to depart the hotel, Booth comes across Lucy Hale, his secret fiancee, with an escort, most likely her sister Lizzie. The public nature of their meeting in the hotel parlor, along with Lizzie’s presence, prevents the lovers from acknowledging each other with anything beyond the same polite pleasantries Booth had just demonstrated with Miss Bean. But the couple still lock eyes and exchange a knowing smile. As the Hale sisters pass him, Booth takes out the image of Lucy he keeps on his person, the same image that will later be found in his pocket diary upon his death. Booth looks upon Lucy’s face before placing it in his pocket. He exits the National Hotel on his way to Ford’s Theatre where he will get confirmation that Lincoln would be attending that night, altering his future, and Lucy’s, forever. If I were to direct such a scene, I pan away from the hotel door after Booth exits out onto the street and turn back to Lucy Hale. Lizzie would be prattling on about something innocuous but our focus would be on Lucy’s face, which would still be a bit blushed from having a small moment of connection with her secret fiancee. She continues ignoring Lizzie and looks at the door Booth exited out of, longing for him to come back. But she never sees him again.

It’s a scene worthy of a theater owner and a pair of star-crossed lovers like John Wilkes Booth and Lucy Hale, but this account is likely just as fictitious as Romeo and Juliet. While John T. Ford no doubt took an interest in learning as much as he could about the events that led up to the President’s assassination at his namesake theater, his absence from the city on the day in question, and his many contradictions throughout the years, make it impossible to put any faith in his accounts regarding Booth’s breakfast. Sadly, aside from John T. Ford, I have been unable to find any compelling evidence to support the idea that John Wilkes Booth had breakfast with Lucy Hale on the morning of April 14, 1865. I don’t believe John Wilkes Booth dined with Lucy Hale that morning. At what point the pair saw each other for the last time will likely always be a mystery.

Epilogue

When I first started reading and doing research about the Lincoln assassination, I avoided the topic of John Wilkes Booth’s romantic entanglements like the plague. Booth was rumored to have been involved with so many different women that the late Dr. Ernie Abel wrote an entire 352-page book about them all. Booth engaged in numerous flings with women that he merely used and then disposed of. While Lucy Hale appears to have been a special case, I still don’t believe that Booth had the capacity to make any long-term relationship work, especially a marriage. Booth was a narcissist with an insatiable desire to be admired and revered. While Booth tried to portray Lincoln’s assassination as an act of justice for the South, it was more an attempt for glory and immortality for himself. Even if he had chosen not to assassinate Lincoln, I believe his relationship with Lucy was still doomed. Booth’s inability to feel fulfilled by any single person would have caused him to stray and ruined Lucy’s life as a result.

With that being said, I do believe that John Wilkes Booth thought he loved Lucy Hale. I say he thought he loved her because I don’t know how capable Booth was of truly loving someone other than himself. Booth’s version of love was not enough to stop him from killing Lincoln, but I believe he did think of Lucy Hale during his final days on the run. In fact, I think he left a final message for Lucy in his diary.

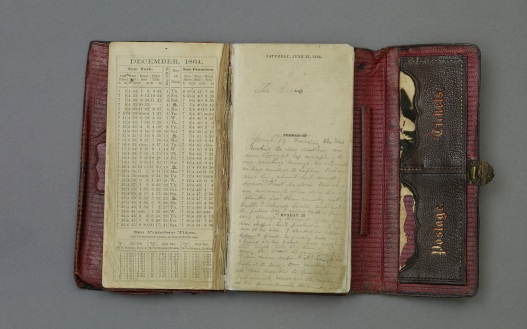

As mentioned earlier, before committing his crime, John Wilkes Booth left a lengthy letter for publication in the newspapers. This was his detailed explanation of why he had taken the drastic action of killing the President. John Mathews destroyed the letter shortly after the assassination for fear of being connected to the crime. While on the run from the authorities, the assassin clambered for newspapers and was dejected to find his words had not been published. Perhaps predicting that he would not survive long enough to try and justify his actions to the world in person, Booth decided to compose another manifesto. With a notable lack of paper, John Wilkes Booth was forced to take down his thoughts in his small datebook from 1864. It was in a pocket of this datebook that he held Lucy Hale’s photograph. Booth ripped out the previously used pages and started the datebook fresh, labeling his main entry as “April 14, Friday the Ides”.

Much has been written about the text of John Wilkes Booth’s diary. Yet, a central section of his diary has been mainly ignored in practically all analyses of his motivations, mindset, and mood. Before writing anything about his deed or his reasonings, Booth opens his diary with two words that stand alone.

The words are “Ti Amo“. The phrase is Italian and translates to, “I love you.”

If Booth had written “I love you” in English, the message could be interpreted as being for anyone, a final note to his mother and siblings perhaps. But writing the phrase as “Ti Amo” codes this phrase in a way that makes it more specific. It is intended for a specific person, who, upon reading it, should know it was for them and them alone.

I contend that this “Ti Amo” was Booth’s final message for Lucy Hale. We know that Lucy was learning Spanish in preparation for her family’s departure to Spain. John Wilkes Booth traveled from D.C. to New York City in March of 1865 in order to visit Lucy, who was taking Spanish lessons in the city. While “Ti Amo” is Italian and not Spanish, it is only one letter different from the Spanish phrase for “I love you”. Perhaps Booth meant to write the Spanish “Te Amo” but ended up with the Italian “Ti Amo” by mistake. Or perhaps the Italian version was a playful response to Lucy’s own “Te amo”. In my view, writing “I love you” in a foreign language in his diary was a way for Booth to announce his love specifically for Lucy without endangering her further by mentioning her name. I might be giving John Wilkes Booth more romantic credit than I should, but I truthfully cannot think of who else this message was meant for other than his secret fiancee, Lucy Hale.

Recent Comments