Thursday, May 25, 1865

Previous Session Trial Home Next Session

- Proceedings

- Voltaire Randall

- Salome Marsh

- Frederick Memmert

- Benjamin Swearer

- William Bull

- Erastus Ross

- John Latouche

- George McGee

- John Caldwell

- Mary Simms

- Elzee Eglent

- Sylvester Eglent

- Melvina Washington

- Milo Simms

- William Marshall

- Rachel Spencer

- Father B. F. Wiget

- Father Francis Boyle

- Father Charles Stonestreet

- Eliza Holohan

- Honora Fitzpatrick

- George Calvert

- Bennett Gwynn

- George Cottingham

- Bernard Early

- Edward Murphy

- Daniel Loughran

- George Grillet

- Henry Purdy

- John Fuller

- George Cottingham (cont.)

- Edward Murphy (cont.)

- George Woods

- Recollections

- Newspaper Descriptions

- Visitors

- References

Proceedings

The court convened at 10 o’clock.[1]

Present: All nine members of the military commission, the eight conspirators, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, Assistant Judge Advocates Bingham and Burnett, the recorders of the court, lawyers Frederick Aiken, John Clampitt, Walter Cox, William Doster, Thomas Ewing, and Frederick Stone.

Absent: Reverdy Johnson.

Seating chart:

“The prisoners were brought into Court about ten minutes before ten; and seated in the same order as they were last week.”[2]

The reading of the brief proceedings from Tuesday’s session was completed by court reporter James J. Murphy.[3]

Walter Cox, lawyer for Michael O’Laughlen, reported on a mistake he found in the transcript of Monday’s proceedings. It related to James McPhail’s testimony regarding Michael O’Laughlen’s oath of allegiance. Cox stated that the transcript reported him as having asked McPhail to read the oath which Cox said was a mistake. In addition, while it was agreed to by Judge Advocate General Holt that the oath would not be entered into evidence since McPhail was not an expert witness on O’Laughlen’s handwriting, the text of the oath was still read into the record by McPhail. Cox asked that the part of McPhail’s testimony relating to the oath be stricken from the record. Holt had no objection to Cox’s correction and the Court ordered the record to be amended.[4]

Testimony began

Voltaire Randall, a detective with the Maryland Provost Marshal, testified about the arrest of Samuel Arnold. Randal stated that he arrested Arnold on April 17th at the store of John W. Wharton near Fortress Monroe, Virginia. The witness was asked to identify a loaded colt pistol that had been taken from Arnold at that time. Randall had written down the pistol’s serial number during his arrest and used it to positively identify the gun.[5]

The Colt navy pistol seized from Samuel Arnold during his arrest was entered into evidence as Exhibit 65.

Salome Marsh, formerly a Union lieutenant colonel in the 5th Maryland Volunteer Infantry, testified about being a prisoner of war at Libby Prison in Richmond. Marsh recounted the deteriorating conditions he had to face during his imprisonment from June 15, 1863 – March 21, 1864. During his time in Libby the prisoner’s rations were cut to little more than corn bread and water. Marsh witnessed many men become emaciated and die. When asked about why their rations had been cut so much, Marsh testified that the officials at Libby told him it was retaliation for the conditions Confederate prisoners of war were facing.[6] Marsh’s testimony had nothing to do with the conspirators on trial but was used by the prosecution to demonstrate the cruelties of the Confederacy.

Frederick Memmert, formerly a Union captain with the 5th Maryland Volunteer Infantry, was captured and imprisoned at Libby Prison during the same period as the prior witness, Salome Marsh. Like, Marsh, Memmert testified about the terrible conditions at Libby and the coldness of the Confederate officers to the suffering of the Union prisoners of war.[7]

Benjamin Swearer, a Union sergeant with the 9th Maryland Regiment and Medal of Honor recipient, was captured and held as a prisoner of war starting in October of 1863. Unlike the last two witnesses, Swearer was held at Belle Isle prison. Swearer testified about the brutal conditions at Belle Isle and that the prisoners were given only half the amount of food one needed to live on. Swearer stated he helped to carry out from ten to twenty dead men a day from the overcrowded prison.[8] Swearer had been the color sergeant for the regiment and was in charge of the American flag. Not included in Swearer’s testimony is the story that, during his five month stay in Belle Isle, he managed to keep the American flag from his regiment safely hidden, first by wrapping the flag around his body. It was not until he had been exchanged and was safely on board a Union steamboat sailing out of Richmond that he revealed the uncaptured flag, much to the excited astonishment of his peers.[9]

William Bull, a sergeant with the Union’s Loudoun Rangers, testified about being a prisoner of war in Andersonville prison in Georgia. Like the similar witnesses before him, Bull described the terrible conditions he faced. Confederate authorities in Georgia took all the prisoner’s clothing, supplies, and money, leaving them with nothing but a pair of drawers and an undershirt. There were no shelters for prisoners and the middle of the prison grounds were like a swamp. Bull described the deaths of many men from starvation, exposure, and dehydration. Bull put a lot of the blame for the mass deaths on the commandant of the prison, Henry Wirz.[10] Wirz would be tried for war crimes later in 1865 and executed. His body was initially buried alongside those of the executed Lincoln conspirators on the grounds of the Old Arsenal Penitentiary.

Erastus W. Ross, a former Confederate clerk at Libby Prison, testified that at around the time of the Union’s failed Kilpatrick-Dahlgren raid on Richmond he was informed by his superior that the prison had been mined. Ross testified that the fuse to the mine of explosive powder was kept in his office with the understanding that, if the Union army came close to raiding the prison, the mine would be detonated.[11] Ross’ testimony and the one to follow supported the prior testimony of Union prisoner of war Reuben Bartley, who stated he saw the area in Libby Prison where the explosive had been buried.

John Latouche, a former Confederate lieutenant with the 25th Virginia Battalion, testified that he was assigned duty at Libby Prison during March of 1864. Latouche oversaw the burial of about 100 pounds of powder in the center of the middle basement of the prison. The powder remained buried there until May when the Libby prisoners were removed. Latouche stated that he heard the commander of the prison, Major Turner, state that if the Union raiders had made their way into Richmond, he would have blown up the prison.[12]

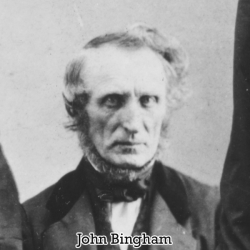

George R. McGee, a Baltimore native and former Confederate soldier, was asked if he knew Samuel Arnold. After replying in the affirmative McGee was asked whether Arnold had ever been in the Confederate army. Before he could respond, Thomas Ewing, Arnold’s lawyer, objected to the question stating that Arnold was on trial for his supposed participation in a conspiracy against the President and not for having been a member of the rebel army. Without admitting that Arnold had been in the Confederate army, Ewing objected to the prosecution’s attempt to conflate his Confederate service with the charges he faced in this court. This led to a long back and forth between Ewing and Assistant Judge Advocate John Bingham in which both men quoted case law in his defense and opposition of the question. Bingham eventually summarized the prosecution’s point of view that Arnold entered into a conspiracy to, “assassinate the President; and that everybody else that entered into the Rebellion entered it to assassinate everybody that represented this Government,” which is why asking about his status as a former Confederate soldier was applicable. Despite Ewing’s disagreement with that conclusion and his response that Arnold, “did not enter into [the conspiracy] to assassinate the President,” the commission overruled his objection. When permitted to answer the question, McGee stated that he was unsure if Arnold had joined the Confederate army. All he would positively state was that he saw Arnold in Richmond sometime during the War, either in 1862 and 1861.[13] We know from Samuel Arnold’s own statements and Confederate records that he was in the Confederate service. For a time he was even in the same regiment (but different company) as George McGee. It’s possible that McGee was deliberately ambiguous and noncommittal with his testimony for the benefit of Arnold.

John L. Caldwell, a clerk at W. S. Matthews & Company in Georgetown, testified that on the morning after the assassination George Atzerodt visited his store at about 8 o’clock. Atzerodt told Caldwell he was going to the country and needed some money. Atzerodt offered to sell Caldwell his watch but Caldwell refused. Atzerodt then presented Caldwell with the revolver he was carrying and asked if he would loan him $10 with the gun as collateral. Caldwell agreed, took possession of the gun, and gave Atzerodt $10. Caldwell was then presented with a loaded gun and identified it as the same one Atzerodt had presented to him that morning.[14]

The gun Atzerodt pawned to John Caldwell was entered into evidence as Exhibit 66.

Mary Simms, an African American woman formerly enslaved by Dr. Samuel Mudd, testified that she lived on the Mudd farm until just after Maryland abolished slavery in November of 1864. Simms stated that in the summer of 1864 she regularly saw John Surratt and other Confederate agents at the Mudd farm on their way to and from Virginia. Simms testified that Surratt and the other men would hide out in the woods near the farm and sometimes come to the Mudd house for provisions that Dr. Mudd provided. Dr. Mudd would also take possession of mail given to him by these men. Simms added that Dr. Mudd would sometimes threaten to send those he enslaved down to Richmond to build batteries for the Confederacy if they did not work hard enough.[15] Thomas Ewing, Dr. Mudd’s lawyer, would later call several witnesses to portray Mary Simms as untrustworthy or confused about the men she saw and when she saw them. However, several other witnesses who were called today would support most of Simms’ testimony and other evidence not connected to this trial shows that Dr. Mudd was involved in the Confederate mail line and assisted underground Confederate activities in Charles County.[16]

Elzee Eglent, an African American man formerly enslaved by Dr. Samuel Mudd, testified that he lived on the Mudd farm until August of 1863. Eglent stated that he escaped from Dr. Mudd two months after the doctor had shot him in the leg and then threatened to send him south to Richmond. Eglent also supported the testimony of Mary Simms, his sister, stating that men dressed in rebel clothing were known to hide in the woods around the Mudd property. The only person he knew among those men was Andrew Gwynn. Eglent stated these men were around the woods in June and July of 1863.[17] Eglent’s testimony was to show Dr. Mudd’s disloyalty to the Union and his reputation as a harsh enslaver.

Sylvester Eglent, an African American man formerly enslaved by Dr. Mudd’s father, testified that, in August of 1863, he heard Dr. Mudd state that he was going to send a group of slaves down to Richmond to build batteries for the Confederacy. Both Sylvester and the prior witness, Elzee, were included in the list of those Dr. Mudd said he was going to send down. Sylvester and Elzee were among a group of 40 slaves belonging to the Mudds and their neighbors who escaped to freedom the following day.[18] After escaping, the Eglents reported Dr. Mudd to Union authorities for disloyalty.[19]

Break

Sylvester Eglent’s testimony concluded at around 1 o’clock. The court then took its normal one hour recess for lunch. During this time the conspirators were returned to their cells. At 2 o’clock, the court reassembled and testimony was resumed.[20]

Testimony resumed

Melvina Washington, an African American woman formerly enslaved by Dr. Samuel Mudd, testified that she had lived at the Mudd farm until she escaped from slavery in October of 1863. Washington testified that she heard Dr. Mudd make disloyal statements about President Lincoln in the summer of 1863 to gentlemen who sometimes hid in the woods near the farm. Dr. Mudd would sometimes carry food to these men and sometimes they would eat at the house with slaves assigned duty to watch the road and let them know if anyone was coming. Washington also stated that she heard Dr. Mudd threaten to send disobedient slaves to Richmond.[21]

Milo Simms, a fourteen year-old African American boy formerly enslaved by Dr. Samuel Mudd, testified that he lived on the Mudd farm until around Christmas of 1864. Simms supported the testimony of his sister, Mary Simms, stating that he had seen men hiding and sleeping in the woods around the Mudd farm in the summer of 1864. Among the men who visited Dr. Mudd during that time was a gentleman whose name was Mr. Surratt. Simms also testified that he heard Dr. Mudd agree with a neighbor’s statement that Abraham Lincoln was a, “god damned old son of a b-tch,” thus showing the doctor’s disloyalty. During Frederick Stone’s cross examination of Simms, he repeatedly asked about when the events with the men in the woods occurred. Simms stayed firm that it happened during the summer of 1864.[22]

William Marshall, a formerly enslaved African American man from Charles County, testified that when his wife was enslaved by Benjamin Gardiner he heard Dr. Mudd speak disloyally with Gardiner. Marshall stated that shortly after the First Battle of Rappahannock Station in August of 1862, Dr. Mudd tended to his sick wife on Gardiner’s property. Afterwards Dr. Mudd and Benjamin Gardiner discussed the battle and Dr. Mudd expressed his affinity for Confederate General Stonewall Jackson. Dr. Mudd also agreed with Gardiner that Stonewall Jackson might soon be making his way into Washington to, “have old Lincoln burnt up in his house.”[23] Marshall’s testimony continued to demonstrate that Dr. Mudd supported the Confederacy.

Rachel Spencer, an African American woman formerly enslaved by Dr. Samuel Mudd, lived at the Mudd farm until January of 1865. Spencer testified that, during the summer of 1864, she observed a group of five or six men who slept in the pines about twenty yards from the Mudd house. The men, who stayed in the area for about a week, would occasionally come to the Mudd house to get food and to sleep. According to Spencer, she understood two of the men’s names to be Andrew Gwynn and Walter Bowie from what she overhead Dr. Mudd saying. Spencer also stated that she heard Dr. Mudd threaten to send one of his men down to Richmond.[24] Spencer’s testimony supported, in part, the testimonies of Mary and Milo Simms in regards to strange visitors seeking shelter near the Mudd property.

At the conclusion of Rachel Spencer’s testimony, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt stated that the prosecution was effectively done with their case. As previously discussed, they reserved the right to call additional witnesses forward who might have relevant testimony regarding the origins of John Wilkes Booth’s conspiracy and evidence that linked his plot to the Confederacy. After conferring with each other, the defense counsels agreed that such prosecution witnesses would not interfere with their cases. At this point the defense began calling witnesses to the stand.[25]

Father Bernadin F. Wiget, president of Gonzaga College, testified about knowing Mary Surratt for about ten years from when her sons attended his school at Chapel Point, Maryland. Wiget was asked about Mrs. Surratt’s reputation and he stated that knew her to be a lady and a Christian. When asked about her eyesight, Father Wiget stated he knew nothing about it and also that the two had never discussed political matters. Frederick Aiken, one of Mary Surratt’s attorneys, then attempted to ask Father Wiget about Louis Weichmann. Specifically, he wanted to know whether Wiget have ever known Weichmann to be a student of divinity. This question was objected to by Assistant Judge Advocate John Bingham who stated that the whole question was immaterial. Aiken shot back that Weichmann had previously testified on May 18th that, during the war, he had expressed a desire to go to Richmond in order to further his studies as a divinity student. Bingham responded stating that he had previously objected to the question regarding Weichmann’s desire to go to Richmond and therefore the question put to the current witness was immaterial to the case. Aiken tried to correct Bingham, who was incorrect in his memory. Bingham had not objected to the asked and answered question of why Weichmann wanted to go to Richmond, but had objected to John Clampitt’s follow up question as to why Weichmann would choose to continue his divinity studies in the Confederate capital when there were plenty of northern divinity schools he could attend. The court sustained Bingham’s objection anyway. Aiken then tried a different route, asking Father Wiget if there were any theological schools in Richmond. Bingham immediately objected again stating the question was immaterial. Aiken, eventually joined by Clampitt, stated that it was the defense’s intent to impeach the credibility of Louis Weichmann and that part of that impeachment was to show that Weichmann had other motives to leave the north and travel to Richmond. Aiken even stated that the defense had abundant proof of what Weichmann really wanted to go to Richmond for. Bingham maintained his objection citing law procedure which stated that a witness could only be contradicted on matters which were relevant to the case at hand. Bingham stated that, “if there is anything irrelevant in the world, it is whether Mr. Weichmann wanted to go to Richmond to prosecute his studies.” In the end, the commission sustained Bingham’s objection and Aiken was forced to drop his questions into Weichmann.[26]

Father Francis E. Boyle, pastor of St. Peter’s Catholic Church in D.C., testified that he had met Mary Surratt eight or nine years ago. He stated his belief that her reputation was of “an estimable lady”. When JAG Holt cross-examined Father Boyle, he admitted to having only spoken to Mrs. Surratt about three or four times in recent years and to not knowing her reputation for loyalty to the Union.[27]

Father Charles H. Stonestreet, pastor of St. Aloysius Catholic Church in D.C., testified that he met Mary Surratt almost twenty years earlier and would occasionally stop and visit at her place in Surrattsville. Father Stonestreet stated that he saw Mrs. Surratt as a, “proper Christian matron,” and that he had never heard her utter a disloyal statement. On cross-examination, Father Stonestreet admitted that he did not believe he had seen Mrs. Surratt since the Civil War began.[28]

Eliza Holohan, a lodger at Mrs. Surratt’s D.C. boardinghouse, testified that she had lived with Mary Surratt since February 7, 1865. Mrs. Holohan answered questions about Lewis Powell’s temporary lodging at the home. Powell had been introduced to her as a Baptist preacher named Mr. Wood and only stayed for a few days. Mrs. Holohan stated that George Atzerodt was an occasional visitor to the house but that Mrs. Surratt stated she did like him sleeping there. John Wilkes Booth stopped by the house during Mrs. Holohan’s residency usually asking for John Surratt, but meeting with Mary Surratt if John was absent. When asked about Mary Surratt’s eyesight, Mrs. Holohan stated that she never saw Mary read or sew by candlelight. The two ladies also attended church together during Lent.[29] Like the Catholic priests who testified before her, Eliza Holohan’s testimony was meant to portray Mary Surratt as a devout Christian and therefore incapable of involvement in such a conspiracy as Booth’s. However, Frederick Aiken’s decision to ask Mrs. Holohan all about the conspirators who visited the Surratt boardinghouse in the months prior to the assassination did little to help his client. During Eliza Holohan’s testimony she stated that as a Baptist preacher she did not think Powell “would convert many souls: he did not look as if he would.”[30] To this, there was laughter in the courtroom and “[Payne, in the prisoner’s dock, here grinned.]”[31]

Honora Fitzpatrick, a lodger at Mrs. Surratt’s boardinghouse, was recalled having previously testified for the prosecution on May 22. Frederick Aiken asked Nora many of the same questions she had previously answered regarding the presence of Lewis Powell, John Wilkes Booth, and George Atzerodt at the Surratt boardinghouse. Nora stated that George Atzerodt stayed only a short time with the Surratts. She also testified that she shared a room with Mrs. Surratt and her daughter Anna. Nora was shown Exhibit 57, the framed image of Morning, Noon, and Night and stated that it belonged to Anna Surratt. She knew nothing of the photograph of John Wilkes Booth hidden behind the image but stated that both she and Anna Surratt had purchased photos of Booth in the past. With direction from Frederick Aiken, Nora testified that Mrs. Surratt had poor eyesight and once failed to recognize a friend walking on the same side of the street. On cross examination Honora Fitzpatrick made it clear that the photographs of Confederate generals that had been found in the Surratt boardinghouse did not belong to her.[32]

George H. Calvert, Jr., a wealthy landowner living near Bladensburg, Maryland, testified somewhat confusingly about a letter he had written to Mary Surratt. At first Calvert insisted that the letter was written on the 12th of May 1865. After some prodding and assistance from Frederick Aiken, Calvert corrected himself to state that the letter was written on April 12th, instead. Before going further, Aiken requested that the government produce the letter written by Calvert to Mary Surratt. Assistant Judge Advocate Henry Burnett stated that the letter would be produced, in time, if it was in the possession of the government. Aiken suspended his questioning of Calvert until such time as the letter was found and brought to the courtroom.[33]

Bennett F. Gwynn, a land agent and resident of Prince George’s County, Maryland, testified that on the day of the assassination he had met Mary Surratt at her tavern in Surrattsville. Mrs. Surratt gave Gwynn a letter and asked him to deliver it to another Prince George’s County resident named John Nothey. Nothey had bought lands from John Surratt, Sr., Mary’s late husband, and Gwynn had acted as an intermediary on the transaction. Gwynn took the letter and read it to John Nothey as requested. Bennett Gwynn also testified about running into John M. Lloyd earlier that day in Marlboro, Maryland. Gwynn testified that Lloyd was not very drunk but had been “drinking right smartly” when he saw him.[34]

George C. Cottingham, a detective on the force of Washington, D.C. provost marshal James O’Beirne, testified that he interviewed John M. Lloyd after the Surrattsville tavern keeper’s arrest. Cottingham proceeded to narrate the manner in which Lloyd opened up to him and confessed that Booth and Herold had stopped by the tavern on the night of the assassination picking up a carbine rifle. Lloyd also told Cottingham about how Mrs. Surratt told him on the day of the assassination to have the firearms ready. Cottingham also described the manner in which the carbine rifle left behind at the tavern was recovered. According to Cottingham, John M. Lloyd openly remarked during his confession, “Mrs. Surratt, that vile woman! She has ruined me.”[35] As a defense witness called by Frederick Aiken, Mary Surratt’s lawyer, Det. Cottingham was a disaster. Rather than poking holes in the testimony of John M. Lloyd, Cottingham supported it. In this instance, however, the blame was not entirely Aiken’s as the lawyer was expecting some very different testimony from this witness. Aiken would recall Cottingham to the stand later in the day in order to explain himself.

Bernard J. Early, the Baltimore tailor who visited D.C. with Michael O’Laughlen on April 13 – 15, was recalled he having previously testified for the prosecution on May 15th. Walter Cox, O’Laughlen’s attorney, had Early testified at length regarding O’Laughlen’s whereabouts during their time in D.C. Early testified that he was with O’Laughlen as various eating, drinking, and entertainment establishments for essentially the entire day of April 13. Early also stated that O’Laughlen was with him from eight o’clock to about ten o’clock on the night of Lincoln’s assassination.[36] The purpose of Early’s testimony was to counter the claims of David Stanton, Kilburn Knox, and John Hatter, who claimed to have seen O’Laughlen outside of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s home on the night of April 13th.

Edward Murphy, a friend of Michael O’Laughlen’s, was one of the men who traveled with O’Laughlen to D.C. on April 13th to witness the Grand Illumination celebration. Murphy mostly reiterated the testimony of Bernard Early in terms of the group’s movements on April 13th. In addition, Murphy stated he was with Michael O’Laughlen during the short period of time when the two of them separated from Early and the others. Murphy testified that O’Laughlen never got close to the home of Edwin Stanton.[37]

Daniel Loughran, a D.C. Treasury department employee and friend of Michael O’Laughlen’s, testified that he met up with O’Laughlen and his Baltimore friends at around 8 o’clock on April 13th. Loughran supported the earlier testimonies of the group’s wanderings over the course of the night and that, at no time, did the men find themselves near the home of Secretary Stanton. Loughran left the group and returned to his home shortly after midnight. On the night of the assassination, Loughran testified he was with O’Laughlen from about 7:30 to 9:30.[38]

George L. Grillet, an agent for a D.C. bakery, testified that he also joined Michael O’Laughlen and his group during the festivities on April 13th. Grillet stated that he was with O’Laughlen when the news of Lincoln’s assassination was made known to them on the night of the 14th but that he did not take notice of his reaction.[39]

Henry C. Purdy, the manager of Rullman’s Hotel in D.C., testified that he saw Michael O’Laughlen at his establishment in the company of the previous four witnesses on April 13th. Purdy stated the men were at his place from about 10:30 to a little past midnight when he closed the bar. On the 14th, O’Laughlen and his friends were back at Rullman’s when the news of Lincoln’s assassination came in. Purdy testified that he was the one who told O’Laughlen about the assassination and that John Wilkes Booth had done it. According to Purdy, O’Laughlen seemed surprised by the news then worried due to his known association with Booth.[40]

John H. Fuller, a bartender in D.C., was a friend of Michael O’Laughlen’s and was with him at Rullman’s Hotel on the night of April 14th. Some time after the news of Lincoln’s assassination came to them, Fuller invited O’Laughlen to spend the night as his place. O’Laughlen left Rullman’s with Fuller and spent the night in the same room as Fuller in the Franklin House hotel. According to Fuller, O’Laughlen stated that the assassination of Lincoln was an awful thing.[41]

George C. Cottingham, the D.C. provost marshal detective who had testified about John M. Lloyd earlier in the day, was recalled by Frederick Aiken. Aiken asked Cottingham the nature of his testimony on the stand in relation to what he had told Aiken earlier. Cottingham then proceeded to admit that, on the evening of May 20th, he had met Aiken at the Metropolitan Hotel. Aiken was interested in Cottingham’s knowledge of John M. Lloyd’s confession. Cottingham refused to restate Lloyd’s confession at that time but agreed to answer any questions Aiken put forth. Aiken proceeded to ask Cottingham if Lloyd had made any mention of Mary Surratt in his confession. Cottingham answered, “no”. It was this answer that caused Aiken to call Cottingham as a witness as it demonstrated that Lloyd’s testimony that Mary Surratt told him to have the shooting irons ready was untrustworthy. Before taking the stand on this day, Cottingham once again stated to Aiken that Lloyd had made no reference to Mrs. Surratt in his confession. After being sworn in, however, Cottingham testified that Lloyd not only mentioned Mary Surratt and the firearms, but that Lloyd had also cursed Mrs. Surratt for getting him into trouble. Now under oath, Cottingham admitted that, in the hotel and before being sworn in, he had lied to Aiken. Cottingham did not believe Aiken had any business to ask him about the content of Lloyd’s confession and that he desired to state everything he knew to the court. Cottingham stated that while he did lie to Aiken, everything he had said on the witness stand had been the truth.[42]

Edward Murphy, Michael O’Laughlen’s friend who had testified earlier in the day, was recalled. Murphy testified that he saw O’Laughlen in Baltimore on the Sunday after the assassination and that O’Laughlen told him he was going to surrender himself to the authorities the next day.[43]

George B. Woods, the Boston Daily Advertiser reporter assigned to the trial of the conspirators, was called to the stand and was asked by Frederick Aiken if he had seen photographs of Confederate leaders for sale in Boston. Woods replied that he had. Aiken then asked Woods if he had seen images of Confederate leaders in possession of loyal Union people. Woods quickly replied that he had[44], but Assistant Judge Advocate John Bingham objected that the question was immaterial and his reply was stricken from the record.[45]

At the conclusion of Woods’ testimony, the court adjourned at around 5 o’clock.[46]

Recollections

“The Court met this morning. The prosecution concluded and the defence commenced. We examined all the witnesses present and adjourned about five o’clock. The weather was very pleasant. The Court room was crowded with visitors. I took a ride round through the city after the Commission adjourned.”[47]

Newspaper Descriptions

“Besides the military officers of the prison heretofore named, under direction of Col L. C. Baker, who frequently visits the prison to see that everything is conducted as the Government wish, four of his officers – John E. Roberts, M. Trial, of Maryland, John B. Hubbard, of California, and Charles E. Fellows, of Philadelphia – are always on duty in the prison, having been within the penitentiary walls ever since the prisoners were removed from the monitors.”[48]

“Gen. Hartranft occupies a seat to-day inside the rail of the Commission, it having been found necessary in consequence of the pressure of spectators to transfer his desk to that point. He is a fine, soldierly looking young man, and attracts much attention as the hero of Fort Steadman. The officers of the Court, altogether, are men of such marked distinction as to make each on an object of eager interest to visitors.”[49]

“An accidental discharge of a guard’s musket in an upper room at the arsenal, to-day, making a loud report, caused considerable flutter, and instinctively suggested Guy Fawkes apprehensions among the crowd. The Court suspended business until the cause of alarm was discovered.”[50]

“Very little latitude was allowed in the evidence, Assistant Judge-Advocate Bingham putting in an objection at every possible point, although the counsel for the defence had sat quietly through the testimony about the Libby Prison and the rebel arson plot. In fact, throughout the trial some of the officers of the government have manifested a constant disposition to discourtesy, which must make the position of counsel for the accused a very unpleasant one. Judge Advocate General Holt is not amenable to this censure, but is always calm and fair, and never forgets his part of gentleman, and that he is in a court of justice.”[51]

“The most profound sensation produced in the court, was by an exhibition of the morals of the detectives of the War Department. Officer Collingham [sic] acknowledged deliberately in open court that he had told Mrs. Surratt’s counsel, so lately as last Sunday [sic], with what motive does not precisely appear, that if called he would swear that Lloyd in his confession never mentioned Mrs. Surratt’s name. He now comes forward and states the very contrary under oath, frankly admitting his previous falsehood. The consternation of the defense and the amazement of the spectators at such a piece of brazen mendacity, may be imagined. The witness was not asked what he received for his services from the department.”[52]

Mrs. Surratt

“Mrs. Surratt occupied her usual seat at the end of the prisoner’s bench. She sat with her veil drawn over her face, her head leaning against the wall, and a large palm leaf fan in her hand.”[53]

“Mrs. Surratt and O’Laughlin seem even more depressed than on Tuesday. Mrs. Surratt sits in her corner ‘all in a heap,’ with eyes half closed and with face shaded with her palm leaf fan.”[54]

“[During the examination of the witnesses in behalf of Mrs. Surratt, she kept her face shrouded from sight.]”[55]

“Mrs. Surratt concealed her face and held frequent consultations with her counsel during the rendering of this evidence, which, on the whole, damaged her case more than benefitted it.”[56]

Lewis Powell

“Payne was dressed in a mixed gray shirt. His face looked whiter than usual, and his hair was more smoothly combed than heretofore.”[57]

David Herold

“Herold occupied his usual seat at the end of the bench, and was attired the same as usual. His beard has grown some length, and he now has chinner whiskers and a moustache.”[58]

George Atzerodt

“Atzerodt presented the appearance which has been so often described. He sat with his body inclined forward, and wears a most villainous look.”[59]

Dr. Mudd

“Mudd was attired in the brown linen coat with a white handkerchief about his neck. He passed most of his time in gazing upon the floor and about the room looking very sad and dejected.”[60]

“[During the testimony bearing on the case of Mudd he appeared considerably excited, rising frequently and stooping over the rail to make suggestions to his counsel. At first he wore a smile of derision, but as witness after witness of his late servants came forward to testify to the same facts, the smile died away and was supplied by an anxious look.]”[61]

Samuel Arnold

“Arnold was dressed the same as on Tuesday, and sat with his head leaning on his hand and gazing through the open window.”[62]

“Either their prison life or the effects of the evidence has given an increased pallor and haggardness to all unless it be Arnold, who is evidently entertaining a hope that nothing can be found to implicate him beyond the attempt to kidnap Mr. Lincoln.”[63]

Michael O’Laughlen

“O’Laughlin was attired the same as Tuesday, and sat with his head thrown back against the wall, his handkerchief in his hand, and gazing about the room.”[64]

Edman Spangler

“Spangler, like Mudd, presented a most miserable appearance, his head inclined forward and his eyes fixed upon the floor.”[65]

Visitors

The Grand Review of the Armies that occurred over the last two days brought a lot of visitors to D.C. and caused the number of visitors to the court room today to swell considerably. Many of the newspapers complained about the number and conduct of the visitors.

“The Court met at ten o’clock this morning, a large crowd of spectators being in attendance at the registry office ready to rush in the moment the door was opened. Among these are a large representation of the Union League of Philadelphia, headed by Wm. Millward, R. K. Smith and Geo. Bullock.”[66]

“Most of those so eagerly pressing for admittance were strangers from a distance, attracted here by the grand review.”[67]

“The Conspiracy Court room to-day was perfectly jammed with spectators. At an early hour the stairways were crowded from the third story to the front door, and a large crowd outside was waiting their turn to be admitted even for a few minutes.”[68]

“As soon as the door was opened there was a rush made by a number of individuals who had secured passes for the purpose of gratifying their curiosity.”[69]

“Long before the hour of opening the Court every seat in the room was occupied, many of the visitors being ladies. Visitors continued to arrive during the morning. In a short time after the Court had been called to order, every inch of standing room was occupied. Seats were arranged in every possible part of the room for the accommodation of the crowd.”[70]

“The little room was crowded to suffocation with spectators of both sexes and during much of the time neither court, counsel, nor reporters could hear a word from the witness stand on account of the ceaseless and senseless chatter.”[71]

“The buzz of eager confab from the ladies seats is quite irrepressible and drowns the opening proceedings of the Court. The windows are kept closed to-day and the atmosphere is pestilent indeed.”[72]

During the testimony of Frederick Memmert:

“[This witness testified also to the cruel treatment he received at this prison, but the confusion in the court room was so great from the talk of the spectators that scarce a word he said could be heard. President Hunter directed that order should be preserved in the room that the reporter might not be incommoded.]”[73]

During the testimony of William Bull:

“[Remainder of the testimony unintelligible from the gabble of the women.]”[74]

During the testimony of John Latouche:

“[The spectators in the court-room kept up such a conversation and whispering that it was impossible for the reporters to get the evidence of this witness.]”[75]

“[At this juncture the ladies behind the reporters commenced some lively comments upon the looks of the prisoners, criticizing the manner in which their hair was combed, or not combed, &c., and for some moments the witness’ voice was drowned, as far as the reporters were concerned.]”[76]

After the lunch break:

“The court-room was densely crowded, every inch of standing room being occupied, a large majority of the audience being ladies, who (God bless them) all newspaper men would thank if they would keep quiet during the examination of witnesses.”[77]

“On reassembling the jam was frightful, and the buzz of eager conversation most animated, particularly when the prisoners were brought in. John Van Buren [son of President Martin Van Buren], Gov. [Andrew] Curtin [of Pennsylvania] and Major General [William Appleton?] Aiken were among the notabilities present this afternoon.”[78]

“The court was crowded with a number of ladies, whose tongues ran incessantly, greatly to the annoyance of our own and other reporters, who were thus debarred from hearing all that was said.”[79]

“A constant stream of visitors poured in and out during the whole day. Those lucky enough to be admitted contented themselves with a brief view of the prisoners, and then retiring to make room for others.”[80]

“Another annoyance is the number of parties present who claim to be ‘reporters’ and ‘correspondents,’ whose only business or object is curiosity. The associate press dispatches are the only ones published in the papers they pretend to represent. These individuals, with a sheet of paper before them, pencil in hand, and with a most profound look of deep thought and brilliant imagination, ape the correspondent, by now and then suddenly catching an idea, which they immediately transcribe on their single sheet of paper, with an alacrity worthy of a better cause than that of a bogus press representative. These fellows do not pretend to represent Philadelphia, New York, or other large places, but some out of-the-way place, away off in the country. In consequence of this evil our reporter was compelled yesterday, to use the crown of his hat for a desk. The heat, the crowd, and the gabble of women present, was enough to turn the brain of any one, except a city reporter; and the reason of this is, he is a perfect salamander – his training immuring him to everything disagreeable and nasty.”[81]

“What should be the most solemn and simple, as it is the most important, trial of the age, is degenerating into a most undignified exhibition of a half-dozen criminals to an unmannerly populace; and if no restriction is put on the daily issue of fresh tickets of admission, the court may as well give up its operations altogether, and place the whole matter in the hands of the people.”[82]

Previous Session Trial Home Next Session

[1] John F. Hartranft, The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution, as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft, ed. Edward Steers, Jr. and Harold Holzer (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 105.

[2] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[3] William C. Edwards, ed., The Lincoln Assassination – The Court Transcripts (Self-published: Google Books, 2012), 476.

[4] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 476 – 477.

[5] Ibid., 477 – 478.

[6] Ibid., 478 – 481.

[7] Ibid., 481 – 483.

[8] Ibid., 483 – 485.

[9] Briscoe Goodhart, History of the Independent Loudon Virginia Rangers (Washington, D.C.: McGill & Wallace, 1896), 113 – 114.

[10] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 485 – 489.

[11] Ibid., 489 – 490.

[12] Ibid., 490 – 492.

[13] Ibid., 492 – 497.

[14] Ibid., 498 – 499.

[15] Ibid., 499 – 504.

[16] Edward Steers Jr., “Dr. Mudd and the ‘Colored’ Witnesses,” Civil War History 46, no. 4 (2000): 324 – 336

[17] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 504 – 505.

[18] Ibid., 505 – 506.

[19] Robert K. Summers, The Doctor’s Slaves: Samuel Mudd, Slavery, and The Lincoln Assassination (Middletown, DE: Self-published, 2015), 38 – 41.

[20] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[21] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 506 – 509.

[22] Ibid., 509 – 512.

[23] Ibid., 512 – 513.

[24] Ibid., 513 – 516.

[25] Ibid., 516.

[26] Ibid., 516 – 520.

[27] Ibid., 520 – 521.

[28] Ibid., 521 – 522.

[29] Ibid., 522 – 525.

[30] Ibid., 523.

[31] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[32] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 525 – 527.

[33] Ibid., 527 – 528.

[34] Ibid., 528 – 530.

[35] Ibid., 530 – 533.

[36] Ibid., 533 – 538.

[37] Ibid., 538 – 540.

[38] Ibid., 540 – 542.

[39] Ibid., 542 – 543.

[40] Ibid., 543 – 545.

[41] Ibid., 545 – 547.

[42] Ibid., 547 – 548.

[43] Ibid., 548.

[44] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 2.

[45] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 548 – 549.

[46] Hartranft, Letterbook, 105.

[47] August V. Kautz, May 25, 1865 diary entry (Unpublished diary: Library of Congress, August V. Kautz Papers).

[48] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[49] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[50] New-York Tribune (New York, NY), May 26, 1865, 1.

[51] Boston Daily Advertiser (Boston, MA), May 26, 1865, 1.

[52] The World (New York, NY), May 26, 1865, 1.

[53] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[54] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[55] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[56] The World (New York, NY), May 26, 1865, 1.

[57] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[58] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[59] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[60] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[61] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[62] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[63] New-York Tribune (New York, NY), May 26, 1865, 1.

[64] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[65] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[66] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[67] New-York Tribune (New York, NY), May 26, 1865, 1.

[68] The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), May 26, 1865, 4.

[69] Daily Constitutional Union (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[70] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[71] Boston Daily Advertiser (Boston, MA), May 26, 1865, 1.

[72] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[73] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[74] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[75] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[76] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[77] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[78] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 25, 1865, 2.

[79] Daily Constitutional Union (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 1.

[80] The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), May 26, 1865, 4.

[81] Daily Constitutional Union (Washington, D.C.), May 26, 1865, 1.

[82] Boston Daily Advertiser (Boston, MA), May 26, 1865, 1.

The drawing of the conspirators as they were seated on the prisoners’ dock on this day was created by artist and historian Jackie Roche.

Pingback: The Trial Today: May 25 | BoothieBarn

Pingback: Formerly Enslaved Voices in the Lincoln Assassination Trial | LincolnConspirators.com

Pingback: 'Manhunt' on Apple TV+: Inside Mary Simms' testimony that pinned Dr Mudd in Abraham Lincoln's assassination - Viral Trunk