IMPORTANT NOTE: Further information as posted in the comments section below has thrown into question whether or not George Atzerodt is actually buried in St. Paul’s. Please click here to read the update to this post. What is without question is that George’s mother Victoria, sister Mary, and brother-in-law Gottlieb Taubert, are all buried in this cemetery.

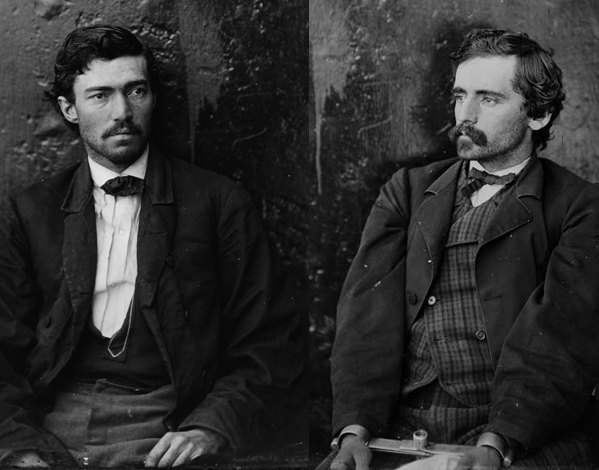

After Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold and George Atzerodt were executed for their involvement in Lincoln’s assassination, their bodies were buried on the Old Arsenal prison grounds. The graves and pine boxes that would hold the quartet are seen in the execution photographs of the conspirators, merely a stone’s throw from where the scaffold stood. John Wilkes Booth’s body had previously been deposited at the Old Arsenal grounds, having been secretly buried underneath the floor of a supply room.

This impromptu cemetery would also hold the body of Confederate officer Henry Wirz after he was tried and executed for the atrocities at his Andersonville Prison. His pine box would lay right along side those of the Lincoln conspirators:

Piece of Henry Wirz’ coffin in the collection of the Smithsonian’s American History Museum.

The bodies of all of these individuals would stay under the Arsenal grounds until the waning hours of Andrew Johnson’s presidency. Less than a month before leaving office, Johnson allowed the family members of the conspirators to take possession of their loved ones bodies. Booth’s body was interred in the family plot at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore. Mary Surratt was interred at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Washington, D.C. David Herold was interred in the family plot in D.C.’s Congressional Cemetery. The final disposition of all of Lewis Powell’s remains is still being researched by his biographer, Betty Ownsbey, but his skull somehow made its way into the collection of the Smithsonian before being discovered and subsequently buried next to his mother in Geneva Cemetery, Florida. While finding Powell’s remains is a more modern mystery, for over a hundred years there was very little known about where George Atzerodt’s final resting place was. Through the research of original Boothies, James O. Hall and Percy Martin, the mystery of George’s burial was solved.

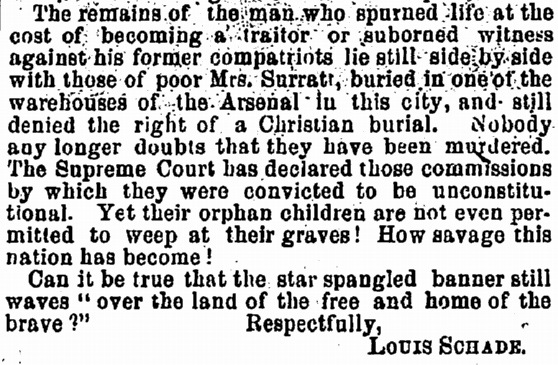

After receiving permission to take possession of his brother’s body, John C. Atzerodt, a former detective on staff of the Maryland Provost Marshal, transferred George’s remains to the northern D.C. cemetery, Glenwood. Records show that on February 17th of 1869, George’s body was placed in a holding vault. John had apparently decided to purchase a lot in Glenwood in which to bury his brother. Some newspapers reported on the arrival of Mrs. Atzerodt from Baltimore to attend the reinterment of her son in D.C.:

It looked like George would spend the rest of eternity in Glenwood Cemtery…

In 1854, the Second Evangelical Lutheran Congregation of Baltimore purchased four acres in Baltimore’s Druid Hill for use as a cemetery. Between 1854 and 1868, the Second Evangelical church divided into three congregations; St. Paul’s, Immanuel, and Martini Evangelical. Each new church held equal control over the Druid Hill cemetery. Together, they sold half of the land to the city of Baltimore decreasing the cemetery to 2.25 acres.

St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran church, one of the three newly formed churches, was located in Baltimore on the corner of Saratoga and Freemount streets. One block south of that intersection was Lexington St. Living on Lexington street and probable members of St. Paul’s congregation was Gottlieb Taubert and his wife Mary. Gottlieb and his wife were both German immigrants. Specifically, Mary Taubert’s maiden name was Mary Atzerodt. She was the daughter of Henry and Victoria Atzerodt, and sister to George. Mary and Gottlieb had married in 1860 when they were 18 and 24 respectively. By 1865, the Tauberts had already purchased a lot in the Druid Hill cemetery, needing it to bury an infant child on April 12th. They would also bury a five year old daughter there in 1866.

On February 19th, 1869, an odd “coincidence” occurs. Just when John Atzerodt needs a place to bury his brother, the Tauberts suddenly have a burial in their St. Paul’s lot. The records back at Glenwood are confusing and missing, but it seems that John Atzerodt never actually paid for the lot he was going to bury his brother in. In fact other people, completely unrelated to the family, are currently buried in John Atzerodt’s supposed lot. George was never buried in Glenwood. Instead of coming to D.C. to attend her son’s reburial, Victoria Atzerodt came to bring her son’s body back up to Baltimore to rest secretly in his sister’s cemetery lot.

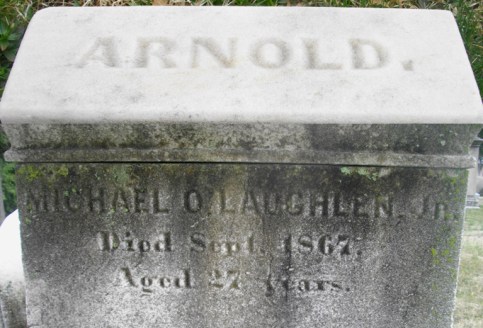

And a secret affair his burial was. So secret in fact, that his name does not even appear in the burial records. The record’s for St. Paul’s cemetery in Druid Hill were not always exact in their documentation. The records were hand written in old German Script and would often be missing several important pieces of information. Whether George’s name was left off of the records purposefully by a sympathetic church clerk, or accidentally by a lazy one, we may never know. What can be gained from the record is that a burial did take place on February 19th in the Taubert lot. In his 1984 article for the Surratt Courier, Percy Martin cited the record as describing the deceased as, “Gottlieb Taubert, aged 29 years”. In the book, Records of St. Paul’s Cemetery by Elaine and Kenneth Zimmerman, they show it as being a “child of Gottlieb Taubert” and being 29 days old. The discrepancies between the two is understandable. Reading handwritten German Script is tedious and difficult. While I have not seen the original record, it is likely that both accounts stated above are different interpretations of the same record. The Zimmermans, familiar with how records for children often lacked any name except for the parent, took “Gottlieb Taubert” to be the name of the deceased’s father. When presented with an age of 29 “years” they fixed what they assumed was a mistake and recorded a more reasonable age for an unnamed child, 29 “days”. Mr. Martin, knowing that the age of 29 years would be consist with George Atzerodt (though George actually turned 30 while in prison), took the name of Gottlieb Taubert to be the name that George was buried as. Either way, Gottlieb Taubert was not a fictitious name as is sometimes stated. It was the name of George’s brother-in-law. The most likely scenario is that George was buried namelessly, and not under a pseudonym. Gottlieb’s name was attached to the record, just like it was for his two young children, because the burial occurred in his lot.

Victoria Atzerodt died on January 3rd, 1886, three months shy of her 80th birthday. She was buried right alongside her poor son George, in the Taubert plot. Gottlieb Taubert, himself, died in April of 1925. The final burial in the Taubert lot was Mary Atzerodt Taubert on September 15th, 1928.

St. Paul’s Cemetery is located in the middle of Baltimore’s Druid Hill park. It is currently maintained by Martini Lutheran Church, the last of the three divided churches still in operation. Though vandals severely damaged many of the stones in the cemetery in 1986, the church has slowly been righting and restoring the stones. The Taubert lot is a vacant one, however. There is no sign that the lot ever bore a stone for any of the Atzerodts or Tauberts.

The name of the cemetery (St. Paul’s) has caused a lot of confusion for those looking to find George Atzerodt’s final resting place. Despite what is on his FindAGrave page, George is not buried in the St. Paul’s cemetery located off of Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd in downtown Baltimore. Rather he is in the St. Paul’s cemetery located in the middle of Druid Hill Park.

Specifically, the Atzerodts and Tauberts are buried in lot #90:

Had it not been for the research of people like James O. Hall and Percy Martin (and our own Richard Sloan, I should add), George’s resting place may never have been known. Discovering his burial site was a product of collaboration. As we continue on in our studies of those involved in the great crime of April 14th, 1865, may we always remember the strength that comes from such cooperation.

References:

The Search for George Atzerodt by Percy Martin in, “In Pursuit Of…Continuing Research in the Field of the Lincoln Assassination” published by the Surratt Society

Records of St. Paul’s Cemetery by Elaine Obbink Zimmerman and Kenneth Edwin Zimmerman

Martini Lutheran Church

Cemetery drawing from the James O. Hall Research Papers

Recent Comments