The first two episodes of the miniseries Manhunt, based on the book by James L. Swanson, were released on AppleTV+ on March 15, 2024. This is a historical review of the first episode, “Pilot.” If you want to avoid spoilers, I suggest you wait to read this review until after you have had a chance to watch the premiere. A separate post will follow, reviewing the second episode, which was also released on this date.

Episode 1: Pilot

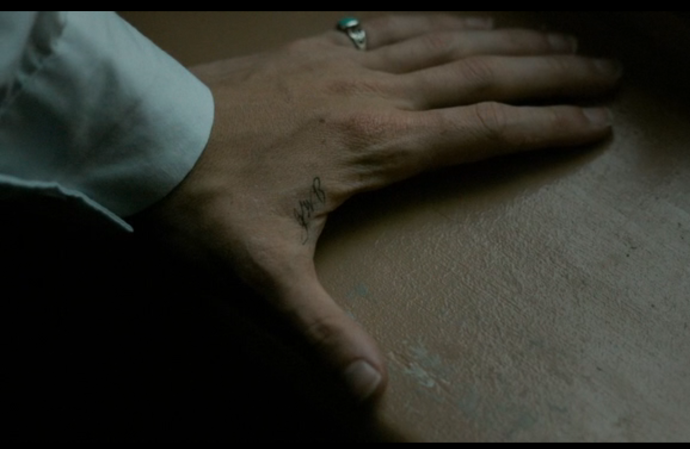

The series opens on April 14, 1865, with the citizens of Washington, D.C., continuing to celebrate the effective end of the Civil War. While the Grand Illumination ceremony was the night before, we are shown residents of the nation’s capital from all walks of life marching, singing, and celebrating. The noise from their revelry causes an unseen man to shut his window forcefully, silencing their voices. Upon his hand, in the webbing between his thumb and forefinger, we see the tattooed initials “JWB.”

In my opinion, this was an incredible way to introduce the audience to the villain of this drama. For the next minute, we follow the assassin’s hands as he readies himself for the events to come. He gathers his weapons and supplies before heading out. He meets up with his fellow conspirator, David Herold, and pays for their rental of two horses. It is then that the first real lines of the show are uttered. Booth tells Davy to, “Round up everybody. It’s a go!”

And with that, the long-awaited Manhunt miniseries begins. Before the title card comes up, we’re put straight into the action. We witness Lewis Powell’s attack on the Seward household before cutting back to Booth eyeing the President and First Lady as they arrive at Ford’s Theatre. We aren’t introduced to our leading man, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, until after the title card fades, and he is alerted to a “break-in” at the Seward home. Then Booth arrives at the backstage door of Ford’s Theatre, where willing stagehand Ned Spangler accepts his duty to hold Booth’s horse even though he has some scene shifting to do inside. Meanwhile, Stanton arrives at the Seward home and sees the vast amount of bloodshed caused by the unknown assailant.

I won’t continue to give an entire play-by-play of the episode here. My ability to describe the events on screen pales in comparison to actually seeing the high production values of the show itself. For the rest of the 54-minute episode, we witness events take place through a combination of tracking events and flashbacks, a style we are likely to see throughout the series. Suffice it to say, this episode covers many different events, including:

- The War Department and President Lincoln receiving word of General Lee’s surrender on April 9

- Booth getting his mail at Ford’s Theatre and learning of Lincoln’s attendance on April 14

- Lincoln inviting Stanton to Ford’s Theatre that night, and the Secretary of War declining

- Booth drinking at the Star Saloon before the shooting

- The assassination of Lincoln and Booth’s leap to the stage

- Booth crossing the Navy Yard bridge out of Washington

- Stanton arriving on the scene outside Ford’s Theatre and making his way into the Petersen House

- Booth meeting up with Herold near Sopher’s Hill

- The death of Lincoln at 7:22 am on April 15

- Booth and Herold’s arrival at the Mudd farm and the doctor’s setting of Booth’s leg

- The removal of Lincoln’s body from the Petersen House

- The search of Booth’s room at the National Hotel

Most of the events not involving Booth have been altered in some form in order to make Stanton the central figure in the drama. Some of the more fictitious scenes are Stanton talking to Peanut John and a meddling newspaper reporter in the lobby of Ford’s Theatre. We also see the Secretary searching the Presidential box himself and finding Booth’s murder weapon. These Stanton-centric scenes, while imaginary, make sense in the context of the show. This is a Stanton series, after all, so he has to be the one calling all the shots and making the big discoveries. Stanton likewise takes part in searching Booth’s hotel room and finds an enigmatic cipher partially burned in the fireplace. The discovery leads Stanton’s number two, Thomas Eckert, to pose the question, “What if the Confederacy is behind the assassination?” This leads Stanton to reply with the episode-ending line, “I’d have to start another war.”

Before getting into the details regarding some of the more fanciful and historically inaccurate moments in the episode. I have a few big takeaways from seeing this first episode.

First, the show looks absolutely fantastic. This was already pretty evident from the trailers, but I was still struck by how amazing the costumes and sets were for this show. Aside from some limitations they had with the interior of Ford’s Theatre, everything in the show looks period. Even some of the outdoor shots, where it’s clear computer-generated imagery was used to create the background of wartime Washington, look well composed. In addition, the editors did a great job when it comes to color-grading the show. The tonal quality of both the indoor and outdoor shots perfectly evokes the time period. There is great attention to detail on the part of the costuming. I was delighted to see Booth’s hand was not only appropriately tattooed, but he wore a pinky ring as he was often photographed with. The fabrics and types of outfits all fit the period and show the variation of styles that existed.

Second, the acting is very good. While I still say that lead Tobias Menzies should have been adorned with Stanton’s signature skunk beard, by the end of the episode, his charisma in the role caused me to forget about it. Menzies plays Stanton in a very sympathetic way in this episode. He’s quite different than practically all other portrayals of the gruff Mars, Lincoln’s own “God of War.” There is logic to this, for while a more cantankerous Stanton might be more accurate, it’s hard to believe an audience would support such a portrayal as their leading man. Over the course of seven hour-long episodes, I’ll take a softer, beardless Stanton that’s easier to empathize with. Anthony Boyle still looks great as Booth and plays the role well. At the moment my only criticism of Booth is more with the writing than the performance. The writing isn’t bad, but it punches down a bit at Booth, removing some of the complexity of his character. He’s referred to as an actor who plays “supporting roles” and one who is “smaller in person.” So far, the only motivation given for Booth’s actions seems to be a professional and personal rivalry between himself and his father/brother. He’s portrayed as a racist, as he should be, but in this first installment, we don’t get a good grasp of why he decided to kill Lincoln. Given the series’ love of flashbacks, I’m hopeful we’ll learn more about Booth’s background in future episodes. My favorite acting performance so far is that of Damian O’Hare in the role of Thomas Eckert. The man looks a lot like Eckert to begin with and, as a sidekick of sorts, he has a lot of great interactions with Menzies’ Stanton. I’m looking forward to seeing more of Eckert going forward.

Third, the music is great. The specially written theme song for the series only shows up at the end as the credits roll. However, the song, written and performed by Danielle Ponder, is incredibly catchy and fits the series well. The underlying score is composed by Bryce Dessner and is a great tonal match for the action on screen. The soundtrack for the series is already available on platforms like Apple Music and Spotify. I’ve been listening to the score while composing this post. There’s some great music to look forward to in future episodes.

Let’s dive now into some of the more, shall we say, “creative” aspects of the show. No single miniseries or movie is going to get things 100% correct, and Manhunt is no exception. As I stated in my post before the series debuted, my purpose in pointing out historical errors is meant to be educational. The benefit of a series like this is that it can generate a lot of questions about what is real and what is dramatized. From what I’ve seen in this first episode, this series will certainly generate a lot of these questions. I’ll be honest and state that there are many errors of fact in this first episode. Some errors are really small, nitpicky things, such as Booth’s diary erroneously having the word DIARY stamped on the front. I will try my best to avoid bringing up too many of these types of mistakes, though some are harmless enough to point out. However, there are also errors or instances of dramatic license that are more significant and can contribute to misinformation about the event if not addressed. Talking about these instances is not meant to detract from the piece as a form of entertainment but to merely make sure there is a record of historical fact to help avoid confusion.

1. Edman Spangler

There was a considerable amount of dramatic license taken in regards to Edman “Ned” Spangler, and his involvement with John Wilkes Booth. Spangler is shown at the start of this episode already behind Ford’s Theatre, waiting for Booth’s arrival before the assassination. Booth’s words to Spangler imply that Spangler is well-versed in what is about to go down. After the shot occurs, Spangler opens the back door of Ford’s for the escaping Booth. He then slams it shut and attempts to block Major Joseph Stewart from getting through and chasing Booth further. When Stanton identifies himself to Spangler the next day, the stage carpenter immediately attempts to bolt, before being apprehended by sidekick Eckert and thrown into a caged wagon.

Practically everything shown in this episode relating to Edman Spangler is fictitious. While Spangler did briefly hold Booth’s horse before passing the job over to Peanut John, there is no evidence that he was aware of the plot against Lincoln. Spangler was friendly with Booth, as many of the stagehands at the theater were (including Peanut John, a white boy who shared a drink with Booth on occasion in the Star Saloon). Spangler was on stage preparing for a scene change when the assassination happened. After the event, he was dumbstruck at what occurred and could not fathom the idea that Booth had committed such a deed. He was “arrested,” interviewed, and released by authorities a few times before he was officially declared a possible conspirator. The main reason Spangler was charged as a conspirator was because the authorities felt that Both had to have had an accomplice inside the theater. However, as the trial went on, it became apparent there really wasn’t much evidence to support this claim. Compared to the sentences of death and life imprisonment that the other conspirators received, Spangler got essentially a slap on the wrist for having been friends with Booth and was sentenced to 6 years. Most historians, myself included, consider Spangler a largely innocent victim of Booth’s machinations. The way he is depicted in this episode erroneously implies that Ned Spangler was far more despicable and culpable than he really was.

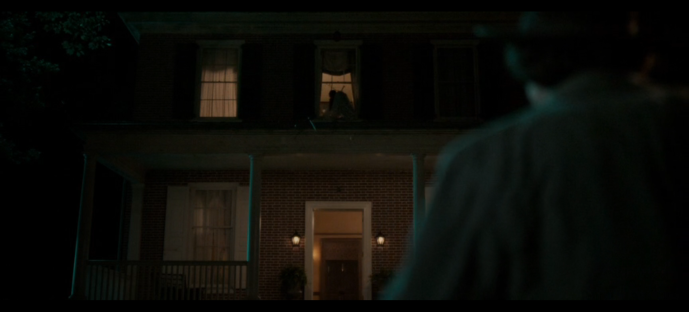

2. The Attack on William Seward

Let’s look at how this episode deals with the attack on Secretary of State William Seward by conspirator Lewis Powell. This whole scene is an example of dramatic license winning out over historical accuracy. For reasons unknown, Powell and Davy Herold arrive at the Seward home sharing a single horse. In reality, each man rode their own, with Powell’s ride being a one-eyed horse that Booth had purchased from Dr. Mudd’s next-door neighbor in 1864. This horse connection would prove damaging to Dr. Mudd at the trial. But that detail aside, the scene plays out with a somewhat dim-witted Powell asking why he is attacking the Secretary of State and what state he is in charge of. Now, Powell may not have been the smartest fellow to ever live, but I’m unsure why the writers dumbed this son of a Baptist minister down so much. Powell approaches the front door to the Seward house and the door is answered by William Bell, one of Seward’s servants. After giving Bell a “genuine pharmacy box,” Powell proceeds to pistol whip Bell out of the doorway. This draws the attention of Frederick Seward, who is also pistol-whipped. When Bell screams for help, Powell aims the gun at the servant and pulls the trigger, but the gun fails to fire. So Powell then attempts to throw the nonfunctional gun at Bell before stabbing him with the large knife Herold gave him. For the rest of the scene of the attack, we remain outside with Davy’s character as he watches silhouettes tussle on the second floor. At one point, two grappling figures break through a window. It’s never clear who Powell is fighting with and what happens to them. Then we see through the broken window Fanny Seward struggling with Powell as she screams for help, crying, “Murder!” This is all too much to bear for Davy, who climbs atop the solo horse and rides away. A few moments later, a blood-covered Powell walks out of the Seward home, realizes Davy has abandoned him, and walks off-screen.

It was an interesting choice to only show this scene from Davy’s perspective. Violence is shown in Powell’s treatment of Bell, Frederick Seward, and Fanny, but the wounds inflicted on the Secretary of State are not shown until Stanton arrives later to take in the scene. The oft-repeated but erroneous claim that Seward’s neck brace saved his life is mentioned by Fanny Seward. In truth, William Seward did not have any sort of neck brace as a result of his carriage accident. While I enjoyed the flashback scene to April 9th in which Stanton and a collared Seward discussed whether this was truly the end of the Confederacy, the large “cone of shame” Seward is shown wearing is just not accurate.

In much the same way, many of the details of Powell’s attack in this episode are incorrect. William Bell did answer the door and allowed Powell entry, but he was never attacked by Powell. It wasn’t until Powell and Bell made it up the stairs and were stopped by Frederick Seward that the scene turned violent. Rebuffed by Frederick for trying to see the Secretary at a late hour, Powell turned as if to leave before brandishing his pistol and aiming at Frederick. It was only after the gun failed to fire that he brought the barrel of the weapon down on Frederick’s head, breaking the weapon and Frederick’s skull. From there, Powell stormed into Seward’s bedroom and frantically stabbed at the Secretary. While he managed two deep stabs into Seward’s face, the quick thinking of army nurse George Robinson prevented Powell from fatally wounding his target. Robinson pulled the assailant off of the Secretary and grappled with him. Augustus Seward, roused by the chaos, arrived in his father’s bedroom and separated the fighting pair. He, like Robinson, received a slashing wound from Powell’s knife as the would-be-assassin ran back down the stairs. On the way down, Powell overcame State Department messenger Emerick Hansell, who he stabbed deeply in the back. Making his way out of the house, Powell mounted his waiting one-eyed horse and rode away while the unharmed William Bell screamed for help from the guards in and around Lafayette Square.

I give credit to the episode for preserving the violence of Powell’s attack. When the assassin emerges, he is covered in blood. When Stanton arrives, he touches blood on the staircase railing in horror. This all fits Dr. Verdi’s assertion that, upon his arrival after the attack, he found the household “weltering in their own gore.” While the tone of the attack is preserved in this episode, a lot of dramatic license has been taken when it comes to the specifics.

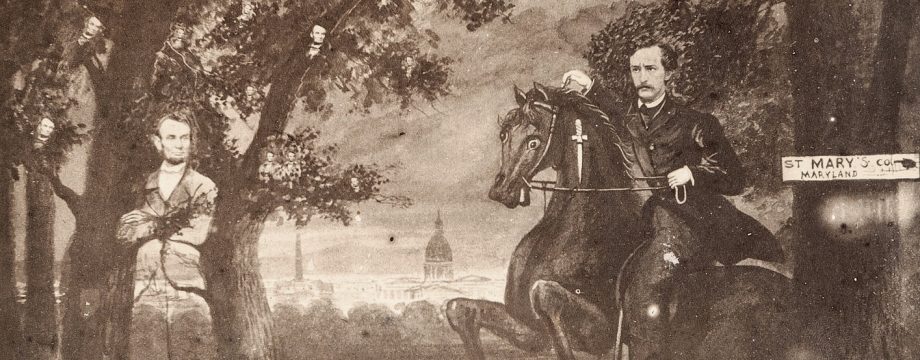

3. John Wilkes Booth’s fame

I think the episode does a great disservice to our understanding of Lincoln’s assassination by negating Booth’s fame and popularity at the time of his crime. The day before the series was released, I saw a clip of this interview that Hamish Linklater, the actor who portrays Lincoln in this series, did for the Associated Press. In the interview, he equated the assassination of Lincoln to what it would be like today if “Leonardo Dicaprio’s brother” killed the President. This, I feel, is a gross misinterpretation of the dynamic that existed between the Booth brothers, and this misconception is heavily portrayed in this premiere episode. It is true that Junius Brutus Booth, the father, and Edwin Booth, the brother, were both very successful theater actors in their day. The elder Booth had died in 1852, making it strange that his photograph is shown adorning the walls of Ford’s Theatre, a playhouse that didn’t exist until a decade later. Edwin Booth was alive at the time of the assassination but never performed at Ford’s Theatre, making it odd that he was also shown on the theater wall.

It is true that Edwin was a point of great success in his career at the time of the assassination. Edwin had just completed 100 nights of Hamlet in New York. The elder brother would go on to be one of the greatest actors of his generation and is appropriately revered in theatrical circles to this day. But, it’s important to remember that John Wilkes Booth was also a star like his brother. This episode continually degrades Wilkes’ fame. He is called a “stuntman” who performs “supporting roles.” During the scene at the Star Saloon, he is encouraged to play the heroes in order to become great like his brother and father. All of this negates that John Wilkes Booth was a truly talented and famous actor who did play the starring roles. John Wilkes had already surpassed his eldest brother Junius, Jr. in terms of acting ability and was well on his way towards achieving the same greatness that Edwin was later known for. Edwin saw the potential in his younger brother, too, supporting his efforts and even writing, “I am delighted with him & feel the name of Booth to be more of a hydra than snakes and things ever was.” While it makes sense to degrade Booth because of his actions, when we discount his abilities or talents, we take away from the shocking nature of his crime. The assassination wasn’t like if “Leonardo Dicaprio’s brother” shot the President. It was as if Leonardo Dicaprio himself killed the President. Booth was near the very top of this game when he chose to abandon the stage and focus on his plot against Lincoln. He wasn’t an anonymous D-list celebrity desperate for attention. He was a man who had everything in the world yet still gave it all up. By simplifying Booth’s actions as intense sibling rivalry gone wrong, we too easily ignore the real lessons that can be learned from analyzing his radicalization from celebrated actor to condemned assassin.

4. John F. Parker

One of the scenes where Booth is compared to his family members occurs in the Star Saloon in the minutes leading up to the shooting. Booth finds himself chatting with a fellow who states that he is the President’s guard for the evening. Booth is elated to find the man responsible for Lincoln’s safety is away from his post and orders a drink for him. This man’s name is John Parker, and after failing to prevent Lincoln’s assassination, he finds himself in a heap of trouble. Both Stanton and Mary Lincoln admonish Parker in this episode for failing to perform his duty.

John F. Parker has gone down in the minds of the general public as the scapegoat for Lincoln’s death, but I believe this is due to our inability to truly fathom a time when Presidents were not constantly guarded and protected. Despite what is shown in this episode, Stanton did not order Parker, or any other guard, to watch over the President at Ford’s Theatre. Lincoln disliked any attempt at protection, even visiting the fallen capital of the Confederacy with little more than a small entourage. There was nothing like our modern understanding of the Secret Service back then. John F. Parker was a D.C. policeman turned White House guard. His job was not to protect the President but the White House itself and its furnishings. He had been hired for the position by Mary Lincoln, who was tired of visitors barging into the White House at late hours or folks attempting to make off with souvenirs from the President’s house. In addition to his role as a White House guard, Parker also acted as a hired night security guard of sorts for different places around Washington. Ford’s Theatre hired off-duty policemen for this role just in case a theater patron was drunk and disorderly during a show. Men like Parker would be there to escort out the riff-raff and keep order. It was usually a fairly cushy gig that allowed one to take in free shows. From the records, it’s unclear in what capacity Parker was acting on April 14. He may have been there as nothing more than an escort for the President and First Lady as they traveled from the White House to Ford’s Theatre. Or he may have been moonlighting as a security guard for the theater. Regardless of his role, Parker had no responsibility to the Lincolns while the show was going on. He was not a bodyguard and did not need to stay close to the President or his party. We know that Parker did get a drink during the performance and even sat and watched the show for awhile. The idea that he shared a conversation with Booth at the Star Saloon is not backed up by any known evidence, and you won’t find the scene anywhere in Swanson’s book.

A lot of the undue hate towards Parker should be rendered moot when you remember that there was a man seated in front of the entry door into the Presidential box. This man was Charles Forbes, the footman who transported the Presidential party to the theater. Forbes and his interaction with Booth were not shown in this episode. My guess is that this is due to the theater set that was used. According to an interview with the lead writer and showrunner, the production had difficulties in finding a “period-correct” stand-in to use as Ford’s Theatre. While most of the miniseries was filmed in Savannah, the interior Ford’s Theatre scenes were shot at the Miller Theater in Philadelphia. The set dressers did a good job of making the stage appear as it did for Our American Cousin, but the rest of the 1918 theater just doesn’t look much like Ford’s. There are no theater boxes, just little mini balconies, and the seats are far too modern-looking. It’s unfortunate that with the money that went into this production, more couldn’t have been allocated to get Ford’s right. I’m okay with other places like Dr. Mudd’s house looking nothing like the real deal, but I think it was a misstep to not recreate the correct setup for the scene of the assassination.

Since the 1918 theater did not have the correct box setup, the series couldn’t show us how Booth was stopped by Charles Forbes. We didn’t see how Booth produced a calling card and presented it to Forbes. We never observe Forbes looking at the card and allowing the very popular actor, John Wilkes Booth, to gain entry to the President’s box in order to pay his respects to the President. Going back to my earlier point, it was Booth’s fame that gave him access to the President. If he was any Tom, Dick, or Harry off the street, I highly doubt Forbes would have let him pass. But for John Wilkes Booth, the accomplished and well-known actor, by all means. Celebrity has its perks.

The reason I relate all this is because, even if John Parker had, for some reason, been seated in front of the President’s box like Charles Forbes was, there is no reason why Parker would have prevented Booth from entering. There was no reason to suspect Booth of anything nefarious. While John F. Parker was far from a perfect person (he was suspended for drunkenness on duty), he is not to blame for Lincoln’s death.

Edit: While watching the scenes of Booth drinking with Parker at the saloon, I couldn’t help but recall a comedy sketch series called The Crossroads of History that the History Channel aired a few years ago. One episode depicted the same fictional scene for laughs with Brian Baumgartner (most famously known as Kevin from The Office) as John F. Parker. There’s a reason the show never had a second season, but there are a couple good laughs in it. Check it out.

5. The Most Famous Man

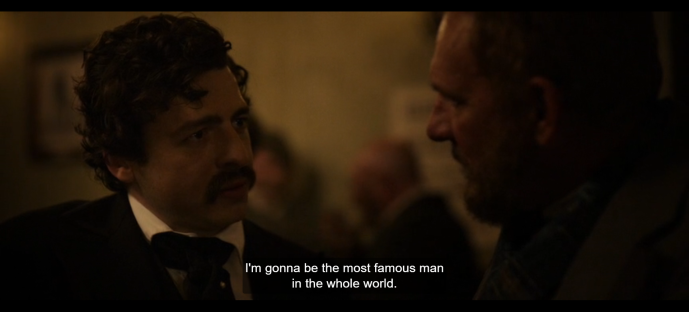

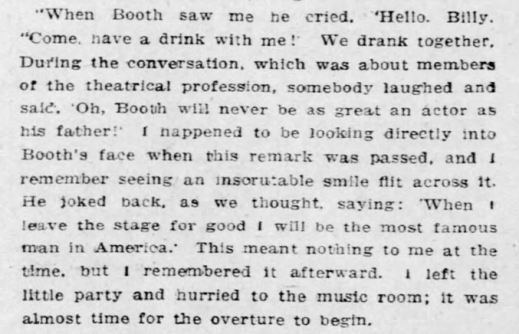

During the drinking scene with John Parker, Anthony Boyle’s Booth pushes back at Parker’s statements about his place in the Booth pecking order by saying, “You know tomorrow, I’m gonna be more famous than anyone in my family.” When Parker presses for more, Booth expands a bit and says, “I’m gonna be the most famous man in the whole world.” This is a good quote and was even included in the trailer for the series. You probably have heard the more common iteration of it: “When I leave the stage, I’ll be the most famous man in America.”

It’s an ominous remark that foreshadows the great drama Booth is about to inflict on the country. But you won’t find this quote in James Swanson’s book. Nor is it in Michael Kauffman’s book, American Brutus, or Ed Steers’ Blood on the Moon. The reason you won’t really find this quote in modern books on the subject of Lincoln’s assassination is because it just isn’t reliable. It’s an example of a quote that comes long after the event and is just too good to be true.

The source for this story is not John Parker, but William Withers, the Ford’s Theatre orchestra leader who got slashed by Booth’s knife as the assassin was rushing backstage after committing the deed. While Withers was an eyewitness to the assassination, his stories regarding the event evolved considerably with each retelling over the years. The way in which Booth slashed at him increased in ferocity, and the wounds that he received grew in size and severity as each decade passed. And it wasn’t until forty years after the assassination that he even mentioned having shared a drink with Booth on that fateful night. The first time this detail appeared was in an interview Withers did in 1905 when he was about 70 years old. The orchestra leader recalled to a newspaper reporter that he shared a drink with Booth just before the overture of the show. However, he made no mention of Booth’s ominous remark about “leaving the stage.” He merely noted that Booth was even more “fidgety and excitable” than usual. By 1911, Withers had altered his story and stated that during their drink at the Star Saloon, someone else at the bar stated that Booth would never be as great an actor as his father. It is in this telling that the “famous” quote appears in print for the first time.

Before his death in 1916, Withers donated the jacket he was wearing when Booth slashed him to the U.S. government. It can currently be seen in the basement museum of Ford’s Theatre. As part of his donation, Withers composed an affidavit recalling his experiences. In this statement, Withers stated that he saw Booth at the saloon, and the actor invited the orchestra leader to share a drink with him. In his version of the tale, it is Withers who “laughingly remarked” that Booth would never be as good an actor as his father. To this, Booth supposedly replied, “When I leave the stage, I will be the most talked of man in America.”

Even after Withers died, the story continued to circulate through his sister, Louisa Withers Beck. She was interviewed on occasion and even appeared on a radio program in February 1939, telling her brother’s story to a national audience. Her versions of Booth’s famous quote differed at times as well.

Likely due to all of the press Withers and his sister were able to garner, the story found its way into books on the assassination. In 1940, newspaperman-turned-author Stanley Kimmel included the “most famous man in America” quote in his book, The Mad Booths of Maryland. It was also picked up by Eleanor Ruggles in her 1953 biography about Edwin Booth, The Prince of Players, and in Jim Bishop’s book, The Day Lincoln Was Shot, from 1955. Bishop’s book was the Manhunt of its day and was incredibly popular. While compellingly written like Manhunt, The Day Lincoln Was Shot does not quite hold up when it comes to accurate history. The concepts of interrogating sources and judging the reliability of stories that changed over time were not as established in these older books of popular history.

Having Booth saying he’ll be the “most famous man in America” just before shooting the President is a good, dramatic quote and fits the style of the vainglorious actor. I don’t fault the miniseries for choosing to include it for dramatic license purposes. And, at the very least, there is a source to back it up. However, as historians, we have to analyze and evaluate sources in order to judge their reliability and validity. As appropriate as I may think it would be for Booth to have uttered these words just before changing the country forever, the source for this quote comes from too long after the event and changes too much to be reliable. That is why modern researchers like Swanson, Kauffman, Steers, and Thomas Bogar (who wrote THE book about the backstage folks at Ford’s Theatre, including Withers) all consider this “famous” quote to be famously apocryphal.

6. The Navy Yard Bridge Crossing

As Anthony Boyle’s Booth attempts to make his escape in this first episode, he comes across the Navy Yard Bridge, where he is stopped by Sgt. Silas Cobb, the officer on duty. Booth demands passage over the closed bridge, but Cobb denies him multiple times, even as Booth claims he desires to see his fiancee on the other side. Cobb then comes close to Booth and asks his name. Booth, apparently fearful to give his name and risk capture, demurs. But Cobb recognizes the actor and releases the tension by singing his praises on the stage. He is ignorant of the crime Booth has committed in the city. After yet another remark about his small stature, Cobb allows the actor to pass, praising his Hamlet as he rides on.

While this is a colorful exchange, the event shown strays pretty far from the known facts. Due to the statement and testimony of Silas Cobb, we actually know quite a bit of the conversation that passed between the men before Cobb relented and allowed the fugitive to pass over the bridge. We know that Booth was halted by Cobb and other guards who informed him the bridge was closed after 9:00 pm to all those without a military pass. However, neither Cobb nor Booth were as aggressive in their dealings with one another as is portrayed in the show. When Cobb asked the man to identify himself, he gave his name as Booth willingly and stated he did not know the rule about the bridge closing after 9:00. He stated he was coming from the city and was heading back home to Charles County, Maryland. When Cobb inquired where his home was in Charles County, Booth replied that he lived near Beantown, a community not far from Dr. Mudd’s farm. Booth also gave his excuse that he waited to depart until after the moon rose so that he would have its light to ride by. Cobb was satisfied with Booth’s answers and told him he would permit the passage but warned the man that he would not be allowed to return to the city until daybreak. Booth, having absolutely no intention of returning to Washington, had no problem with this directive and crossed the bridge.

I debated including this scene in my review because, on the face of it, it doesn’t really detract from the history to create this more humorous exchange between Booth and Silas Cobb. However, the bigger issue is that the show also fails to include the crossing of Davy Herold a few minutes later and, more importantly, the arrival of stableman John Fletcher a few minutes after that. At the very beginning of the episode, Booth and Herold are shown picking up horses from Pumphrey’s stables. While Booth did rent his bay mare from Pumphrey, David Herold did not. His horse came from Naylor’s Stables, where John Fletcher acted as stableman. This seemingly minor detail is important because Davy did not return his rented horse on time angering Fletcher. George Atzerodt, an acquaintance of Herold’s, came to Naylor’s Stable that evening just before the assassination and invited the stableman for a drink. During their drink together, Fletcher complained to Atzerodt that his friend had not returned his horse yet. Atzerodt tried to smooth things over before he departed towards the Kirkwood House, where he failed to carry out his assigned role. Not long after this, John Fletcher saw Davy Herold riding the overdue horse down the street and halloed for him to return it. Rather than dealing with Fletcher, Davy galloped away and headed towards the Navy Yard bridge. Fletcher returned to his stable, mounted up a horse, and gave chase. When Fletcher arrived at the Navy Yard Bridge, he learned from Cobb that he had just missed Davy, who had been allowed to cross over. Cobb offered to let Fletcher cross in order to chase the suspected horse thief further, but Fletcher did not want to be stuck outside the city until daybreak. As a result, Fletcher turned around and reported his missing horse to the Metropolitan Police. He connected Herold to George Atzerodt and John Wilkes Booth, all of whom had used each other’s horses and tack over the past few months. Fletcher’s report helped the authorities connect Booth with two of his fellow conspirators far more quickly than they might have discovered on their own.

The series has removed John Fletcher entirely. Herold is later shown in Southern Maryland waiting for Booth with no explanation of how he got past Cobb at the bridge. Rather than having Fletcher help connect the dots for the authorities, the series commits its next major faux pa.

7. George Atzerodt Just Gives Up

I’ll admit that I guffawed a bit when George Atzerodt made his not-so-subtle appearance in this episode. While we are left to deduce the identity of Lewis Powell (who, for some reason, is at Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse rather than his hotel on April 14), the creators decided to give Atzerodt a big goofy sign the first time we meet him. Atzerodt has the appearance of a beggar and I’m amazed any hotel employee would allow him to solicit in such a manner in their nice hotel. Not to mention that Atzerodt’s carriage business was down in Port Tobacco, Maryland, and had shut down several years before. But if you want to make Atzerodt a laughable caricature, that’s fine.

The real issue is how this series claims that Atzerodt is arrested almost immediately. Just a few minutes after Stanton arrives at the Petersen House and sees the fatally wounded President, he’s told that Atzerodt is in custody and that he admitted Booth told him to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson. In reality, of course, George Atzerodt spent the night of April 14 drinking, riding the horse-drawn trolley, and then crashing at the Pennsylvania House Hotel. The next morning, he woke early, skipped out on paying his room bill, and caught a stagecoach out of Georgetown heading northwest. By this time, the military had shut down D.C., so he was prevented from crossing out of the city. Eventually, new orders came in on the afternoon of the 15th, opening some traffic back up, and Atzerodt conned his way into a ride out of Washington. He made his way up to Montgomery County, Maryland, and went to his cousin’s farm near Germantown. He was eventually tracked down there (due to the initial hint by John Fletcher) and arrested on April 20th.

It is regrettable that Atzerodt’s whole story had to be dispensed with, seemingly for convenient exposition purposes. But, with only 7 hours to tell a compelling Stanton story, I suppose cuts had to be made somewhere. Sorry, George.

8. Now He Belongs to the ____

I want to start off and say that I largely liked the scenes at the Petersen House. I was especially moved by Stanton’s first appearance in the death chamber. No words are spoken, and the emotional weight of the dying President comes across very well. Stanton’s well-known reaction to Mary Lincoln’s understandable hysteria is shown in a more sympathetic way in this episode. While it may not be the most accurate, I actually prefer how their exchange occurs here. However, it is strange that Mary Lincoln was not just removed from the death chamber but apparently sent all the way back to the White House. I’m not sure that is accurate. Later, when Lincoln’s casket is brought out of the Petersen House, Stanton’s comment about the old Rail Splitter and the overhead shot of the coffin going down the stairs are both quite moving.

I do feel that the show missed an opportunity to actually show Stanton doing his job while at the Petersen House. While it appears that Tobias Menzie’s Stanton is destined to be the Forest Gump of the manhunt, showing up everywhere and making all the important finds, in reality, Stanton was only slightly involved in the manhunt. He was first and foremost the Secretary of War during a time when the Civil War was very much still going on. Despite the claim this Stanton makes at Ford’s Theatre when he tells the box office manager that he doesn’t know how to delegate, the real Stanton knew the importance of finding creating a team and delegating tasks to them. He set up many special commissioners and investigators to help track down Booth while he acted as an overall manager of the manhunt. Truthfully, the area in which Edwin Stanton really seemed to take on the most individual action himself was in the hours at the Petersen House while the President lay dying. From the front parlor, Stanton communicated and coordinated with the generals in the field and started the collection of witness statements. It has often been said that as the President lay dying, Stanton was the effective head of the United States. While I suppose it’s possible we may see some of this as a flashback in a later episode, I was disappointed that Stanton’s true heroic time to shine was not portrayed.

However, my main criticism of the Petersen House scenes is the moment of Lincoln’s death. When it comes to Edwin Stanton, he really has one big line that everybody knows, even if they don’t know who its from. It’s the phrase that is carved in gold letters in the burial chamber of the Lincoln Tomb in Springfield. Say it with me now: “Now he belong so the ages.”

It’s such an iconic phrase that I don’t even mind that it is far more likely that Stanton didn’t say anything at all. In truth, the phrase doesn’t appear in print until 1890, making it as suspect as Booth’s “most famous man in America” line. But the “Ages” quote seemingly transcends questions of reliability, and I’m pretty fine with that.

But what I’m not fine with is, “Now he belongs to the angels.” My friend and fellow researcher Scott Schroeder has done a great amount of research into Stanton’s famous deathbed quote. He acknowledges that the provenance of “Ages” is a little suspect but that at least three people who eventually included this quote in their writings were present at the Petersen House while Lincoln was dying. How many primary sources quote Stanton as saying “Angels”, you ask? None. Zip. Nada. Zero. All of the sources that attempt to argue that Stanton said “Angels” are from secondary sources, the first of which doesn’t appear until 1922. The argument is usually along the lines that, as a religious man, Stanton surely would have said angels instead of ages.

I can’t fault the series for putting “angels” into Stanton’s mouth because James Swanson is one of the few authors who inexplicably supports “Angels” over “Ages.” So, in my opinion, this is a flaw in the source material.

The most likely scenario is that Stanton, overcome by grief, had nothing poignant to say at the moment of Lincoln’s passing. This is how Michael Kauffman recounts the scene in his more scholarly book, American Brutus. But, if we give some of the later accounts a greater degree of leeway than we probably should, then the iconic line of “Now He Belongs to the Ages” is what Stanton should have said.

9. Visiting “The Crime Scene”

In this episode, Edwin Stanton makes many important discoveries when he visits Ford’s Theatre himself for a little investigating. From “Jessie,” the box office manager who had told Booth about Lincoln’s planned attendance, Stanton acquires a large imperial photograph of Booth, apparently from a run of shows he did at Ford’s a few weeks prior. There’s a great shot of Booth’s derringer on the floor of the President’s box, which Stanton finds and picks up. Eckert arrives and suggests they talk to more of the staff. The duo then chats with Joseph “Peanut John” Burroughs, who hesitatingly recounts his involvement in holding Booth’s horse. Peanuts is full of helpful information, such as the appearance of Booth’s horse, the way in which the assassin rode, and that he was on a rented city horse that would need food soon. Peanuts also rats on Spangler leading to the stagehand’s arrest.

Most of what is depicted in these scenes is fictional. As far as I know, Ford’s Theatre did not have a photographic wall of fame, as it were. I find it hard to believe that a theater would pay to photograph each of its performers, particularly a “supporting” actor, as they claim JWB to be in this series. The “Jessie” who talks with Stanton is not a real person but is probably meant to personify Harry Clay Ford, one of the three Ford brothers and the daily manager of the theater. Harry is the one who talked to Booth when the assassin got his mail on April 14.

The person who found Booth’s derringer on the floor of the box was not Stanton but a man by the name of William Kent. This theater patron had made his way into the box after the shot and offered his penknife to Dr. Leale who used it to slice Lincoln’s shirt. After the unconscious President was removed to the Petersen House, Kent realized he had lost his house key during the chaos. He returned to Ford’s and searched the box for his key. Instead, he found the murder weapon. Lawrence Gobright, a member of the Associated Press, was in the theater at the time as well, and he took possession of the weapon from Kent. Gobright later gave the gun to the War Department. Despite Stanton’s claim in this episode that “This is a crime scene,” such a phrase would have been meaningless back then, and there was no real effort to secure the box. Another theater patron walked off with the wooden bar that Booth had used to wedge the outer door of the theater box shut. He took it home with him and even cut a piece off of it to give as a souvenir to a friend before authorities heard about it and sent men out to reclaim this piece of evidence. This practice of collecting and selling relics of the assassination is actually well demonstrated in the scene where Stanton chastizes a street vendor hawking Lincoln masks, playbills, and a sconce he swiped off a wall.

The Peanut John in this series must have superhuman and X-ray vision. From his spot in the alley behind Ford’s Theatre, which exits onto F Street, Peanuts was apparently able to see Booth riding two blocks to the north “Down H Street” all the way “To Anacostia,” which is about four miles to the southeast. While the real Booth did ride towards Anacostia, there is no reason why he would have gone out of his way to head north first to H Street before turning and heading southeast. Either this was just a mistake from a lack of understanding of the geography of D.C., or the series is setting up for a future flashback in which the escaping Booth stops at Mary Surratt’s D.C. boardinghouse for some reason. We’ll have to wait and see.

Did anyone else openly laugh at the idea that Stanton could single-handedly ban the sale of horse feed in the state of Maryland? Apparently, all horses in Maryland have to starve now because Booth escaped into that state on a city horse. It’s such a ludicrous and silly concept.

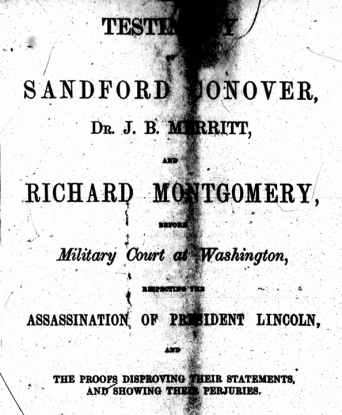

10. Sandford Conover

While Stanton is investigating at Ford’s Theatre, we are introduced to a new character that I didn’t expect to see at all, and definitely not in the first episode. Actor Josh Stewart appears with mutton chops and introduces himself to Stanton as Sandford Conover, a reporter with the New York Tribune. Conover somewhat aggressively interrogates Stanton, but the Secretary of War allows it by putting Conover to work in getting a photographer to come and photograph the “crime scenes.” The words between Conover and Stanton were clearly written to echo our modern-day events, with Stanton’s line, “This is America. We replace our presidents with elections, not with coups,” being a pointed reference to the January 6th insurrection.

I had seen Josh Stewart’s face in the trailers, but IMDB had only identified him as “Wallace.” At the time, I predicted that this was a mistake and that he might be playing the role of John M. Lloyd, the renter of Mary Surratt’s tavern. Now that I know he is playing Conover, the “Wallace” name makes sense. Here’s some background on Mr. Conover from my Lincoln Conspiracy Trial project:

Sandford Conover was a key witness for the government’s case regarding the involvement of Confederate officials in Lincoln’s assassination. At the trial of the conspirators, he testified at length about meeting with important members of the Confederate Secret Service in Montreal, Canada. According to Conover, he was born in New York but was in South Carolina when the Civil War broke out. He was drafted into the Confederate army, where he worked as a clerk in Richmond. Conover stated that in December of 1863, he deserted from the Confederacy. In October of 1864, he made his way to Canada, where he used the alias James Watson Wallace. During his time in Canada, Conover gained the trust of notable Confederate agents like Jacob Thompson, George N. Sanders, Beverly Tucker, William C. Cleary, and others. Conover stated he saw Booth in Montreal in October of 1864 and that John Surratt was there four or five days before the assassination of Lincoln. According to Conover, the assassination of Lincoln was discussed openly with him by Jacob Thompson in early February of 1865, and Thompson even encouraged Conover to join Booth in the plot. Conover described seeing blank commissions for the Confederate army signed by the Confederate Secretary of War. These commissions were to be filled in by agents in Canada with the names of anyone who committed acts of guerilla warfare on the Confederacy’s behalf. Conover stated that a commission had been made out for Booth so that, in the event he was captured in Canada after assassinating the President, he would be considered a Confederate officer and not liable for extradition. As a witness, Conover linked the Confederate agents in Canada to every act of black flag warfare, including Lincoln’s assassination. Unfortunately, all of Conover’s testimony was later discovered to be false.

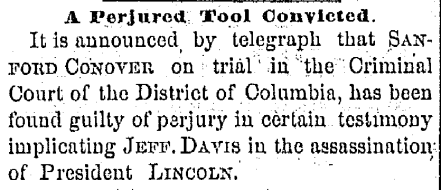

In June of 1865, Sandford Conover’s previously secret testimony was leaked to the press, and it quickly unraveled. Conover claimed that, during his time in Canada, he was acting as a secret correspondent for the New York Tribune. He testified that he had written to the New York Tribune in February and March of 1865 about the plots against Lincoln. These claims were later denounced as false by the editors of the New York Tribune. The Toronto Globe investigated some of Conover’s claims and found that not all of the men Conover testified about meeting with were present in Montreal during the time periods Conover swore to. Worried about the damage Conover’s perceived perjury would do to their case against Confederate leaders, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt ordered that all of the suppressed testimony be published, including the prior testimonies of Dr. James Merritt and Richard Montgomery. Both Merritt and Montgomery testified about conversations with Confederate officials about the proposed assassination of Lincoln, thus supporting Conover’s claims. All three men would later be recalled to the witness stand in the closing days of the trial in order to counter claims of perjury in the press and help salvage the government’s case against the Confederacy. But the press continued to investigate and poke holes in the claims made by these men. On the day of the four conspirators’ execution, the Toronto Globe published a letter from Sandford Conover to Confederate Secret Service agent Jacob Thompson dated March 20, 1865, in which Conover introduced himself to Thompson. This showed that, contrary to Conover’s claim to have been intimate with Thompson since the fall of 1864, Thompson had never heard of Conover prior to that date. In the end, the perjury of Conover and the others was conclusively determined in 1866 when James Merritt testified before a congressional committee. Merritt admitted that both he and Richard Montgomery had committed perjury in their testimony against Confederate leaders. According to Merritt, Conover had secured both men to lie, and they had been paid for their services. Later, in November 1866, Sandford Conover, whose real name was Charles A. Dunham, was indicted for perjury. He was found guilty and sentenced to ten years in prison.

After reading this, you’ll understand my surprise at Conover making an appearance in this first episode. If he was going to show up at all, I figured it would be later when the trial of the conspirators was shown. Conover was a grifter and a liar who only wanted to milk the government for whatever funds by telling them exactly what they wanted to hear. At the time of the assassination, Conover/Wallace/Dunham was in Canada, not in Washington. He showed up sometime in the weeks after the murder with his valuable information to sell. Desperate for a smoking gun connecting Booth’s plot with Confederate leaders, Conover duped the Judge Advocate General into giving him funds to continue his own “investigations” in Canada. From what I can see on IMDB, it looks like Conover is going to continue to play a role in this series, at least in the first four episodes. So I guess we’ll see how this storyline plays out differently from the real Conover.

11. Ummm… We missed a stop

Oddly, the series fails to show a key moment in Booth’s escape: his first stop. After crossing the Navy Yard Bridge and meeting up with David Herold, the real John Wilkes Booth stopped first at Mary Surratt’s Tavern in Prince George’s County. While there, the pair wakes up the tavern keeper, John M. Lloyd, and orders him to “make haste and get those things.” They are referencing a pair of Spencer repeating carbines that had been hidden at the tavern during the abduction plot as well as a pair of field glasses that Mary Surratt had dropped off at the tavern earlier that day. Lloyd brings these items out while Booth, suffering from a broken leg, stays on horseback. The pair are only at the tavern for a few minutes and ride off after telling Lloyd the news of Lincoln’s assassination.

None of this is shown in the series. After seeing Booth and Herold meet up in Maryland, the next time we see the fugitives is as they are riding up to Dr. Mudd’s house. I know that this is the Stanton show, so some aspects of Booth’s escape are going to need to be shortened. But I figured they would sort of gloss over Booth’s time hiding in the woods to keep the narrative moving, not cut out the assassin’s first stop and the character of John M. Lloyd altogether. It’s going to be hard to really get into Mary Surratt’s character and suspected culpability without showing this first stop and her contribution to it. But, as I’ve said before, the series loves flashbacks. So perhaps, in a later episode, we’ll see Booth and Herold at the tavern. In the meantime, though, I am very disappointed that a key part of Booth’s escape has seemingly been cut out.

12. Dr. Mudd’s

In this first episode, we see Booth and Herold riding up to the Mudd farm during daylight with the doctor seemingly expecting them. Mudd helps Booth off his horse as the assassin winces in pain. Inside the house, Dr. Mudd is shown cutting Booth’s boot and pulling it off, revealing a badly broken leg. David Herold then enters the room with the morning’s paper saying that Booth is front page news. Before Booth can read it, Dr. Mudd grabs the paper from Herold’s hands and sees the headline announcing Lincoln’s assassination. He seems shocked by what is written before Booth grabs the paper from him eager to “read his reviews.” Mudd leaves the room, having been ordered by Booth to fetch more whiskey. Booth reads the paper ignoring the mournful cries for Lincoln until he reads something about him being a symbol for the cause, which brings him joy. As Booth and Herold are celebrating, Mary Simms, one of Dr. Mudd’s servants, enters the room with coffee for the men. Booth only gives his name as “Sir” and makes a disparaging and sexist remark to Mary. Dr. Mudd reenters the room with whiskey and orders Mary to “have her brother make a splint.” When she reminds Mudd that her brother had just finished working on a latrine, the doctor scolds her and says he’ll work as long as he says. The doctor also says that he “taught him a lesson last year” and threatens to do the same to Mary. When Mary exits, Mudd prepares to set Booth’s leg. He suggests Booth hold Herold’s hand for the pain, but Booth declines. After a count of three, Mudd presses down hard on Booth’s leg, which is accompanied by loud cracking noises and Booth screaming in pain.

The scene at Mudd’s in this episode lasts less than three minutes. Yet almost everything shown in this scene is historically wrong. Here’s a breakdown:

- Booth and Herold arrived at the Mudd farm in the dark at around 4:00 am. No one was expecting them, and it took quite a while for Dr. Mudd to stir.

- The series has given Booth a broken right leg. The real Booth broke his left leg.

- This Dr. Mudd states that Booth’s tibia bone is broken. The real Booth broke his fibula.

- The break is shown to be near his knee. The real break was down near Booth’s ankle.

- There was no newspaper delivery to the Mudd farm, and even if there was, there was no way that a local Bryantowon paper would have the news of Lincoln’s assassination that quickly.

- The paper even reports that Lincoln was dead, but at the time Booth and Herold got there and Booth was receiving treatment, Lincoln was still alive.

- As I’ve noted before and will again in the future, Mary Simms did not live at the Mudd house in 1865. After the new Maryland state constitution prohibiting slavery took effect in 1864, Mary Simms was freed and left the Mudd farm for good.

- There were two formerly enslaved girls who stayed with the Mudd family after emancipation, worked for them as paid servants, and cooked and served John Wilkes Booth his breakfast on the morning of April 15. They were Lettie Hall and Lousia Cristie. It’s a shame the series excluded them.

- The real Mary Simms had two brothers who had been enslaved by Dr. Mudd: Milo Simms and Elzee Eglent. Neither of these men were still at the Mudd house when Booth was there. The older brother, Elzee Eglent, had been shot in the leg by Dr. Mudd in June of 1863, which seems to be what the character of Mudd is referencing in this scene, but his timeline is off. Elzee then escaped to freedom in August of 1863, never to return. Milo Simms was Mary’s little brother and he left the farm when slavery was abolished in 1864. So, like Mary, there was no brother of Mary Simms living at the Mudd house in 1865.

- The real Dr. Mudd made Booth’s splint himself out of an old hatbox.

- Dr. Mudds’ knowledge of the identity of his visitors is disputed. I won’t go too far into this because I personally feel that Dr. Mudd was well acquainted with who he was treating from the moment Booth arrived. However, I will state, for fairness’s sake, that the statements from Dr. Mudd and his wife claim that the wounded man wore fake whiskers and kept his face fairly well concealed during his time at the farm. I’m of the opinion that they said this to protect themselves and give themselves some plausible deniability for when it was discovered that Booth had visited the Mudd farm in the past. I’m actually okay with Mudd clearly recognizing Booth as is shown in this series. But the manner in which this Mudd learns of Lincoln’s assassination from the seemingly clairvoyant local paper is beyond belief. It would have been better for the series to either show Booth openly bragging to Mudd about the shooting or for it to wait and have Dr. Mudd learn the news of Lincoln’s death, as he himself claimed, during this trip into Bryantown with Davy Herold later that afternoon.

It’s pretty clear that this series is going to take a lot of liberties when it comes to the story of Dr. Mudd.

13. Searching Booth’s Hotel Room

Once again, Edwin Stanton is the prime mover, searching Booth’s room at the National Hotel himself with only his sidekick, Thomas Eckert, for company. Among the ashes of burned papers, Stanton finds a slightly singed coded table which he brings to Eckert’s attention. Eckert doesn’t recognize the pattern but suggests that the code could come from Richmond, Montreal, or just be Booth, “playing spy games.” Spoiler: It’s the latter option, but that doesn’t make for good TV. They continue searching the room, and Eckert finds a bank book from Montreal. Eckert notes that Montreal is a known hotspot for the Confederate Secret Service. With this circumstantial evidence in their hands, the episode closes with Stanton pondering the repercussions of Confederate involvement in Lincoln’s death.

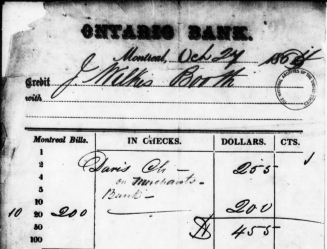

Overall, I like this scene and the relationship shown between Stanton and Eckert. It’s also a great way to end the first episode and definitely makes me want to see more. Did Stanton or Eckert take part in the searching of Booth’s hotel room? No. Other, real detectives did that. Was a code table and a Montreal bank book found among Booth’s papers? Yes. They were among several items and papers seized from the National Hotel. Would Eckert have been uncertain about the coded table that was found? No. Vigenère tables were very common in Eckert’s line of work and the head of the military telegraph and accomplished codemaker would have recognized it immediately.

John Wilkes Booth did deposit $455 into a Montreal branch of the Ontario Bank on October 27, 1864. At the same time, he purchased a bill of exchange for a little over 61£. Copies of this bill of exchange were found on Booth’s person upon his death at the Garrett farm. The purpose of the money in Booth’s Canadian bank account is unknown. He never withdrew or used the money. I’m not surprised this series has decided to use this enigmatic deposit to tease possible Confederate involvement. Many authors and researchers have attempted to connect the same dots, though, in my opinion, none have done so convincingly. We’ll have to wait and see how this series presents its case.

Well, that was long. If you’ve made it to this point, then I commend you for sticking with me. As you can see, there are many historical inaccuracies in the series. I’ll admit that my initial reaction after finishing the first episode was one of disappointment. I had hyped myself up so much and had such high expectations for the series that seeing silly errors like Booth breaking the wrong leg angered me. But, at the same time, I know that historians are the hardest audiences to please. We want everything to be correct, but that is, at its core, an impossible task for any piece of entertainment. This series was not intended to tell the absolutely true story of Lincoln’s assassination. It’s intended, like all drama, to tell a compelling story.

When I turn off my historian brain and allow myself to watch the series as a period drama with familiar characters, I find that I enjoy it. To quote from one of my favorite TV shows of all time, “Just repeat to yourself, ‘It’s just a show. I should really just relax.'”

Do I wish that more attention had been paid to the source material that this series is supposed to be based on? Of course. But I’m not going to angrily trash the series as a whole for going “off-script” with its portrayal of history. I will continue to watch the show and produce reviews like this that point out errors and instances of dramatic license. These historical reviews are not meant as a dig against the creatives behind the show, but as a way to show that even flawed representations of history can be used as educational tools for helping folks learn more about this important event.

So, come back and read my historical reviews for the rest of the episodes of Manhunt as they are released. I’m confident that you’ll learn something from them.

Dave Taylor

(Note: I’ll need a few days before I can put up the review for episode 2. This one took me several hours to research, write, and illustrate.)

disappointing with made up scenes and miscasting. The truth and the book is perfect for storytelling i see no need to make up falsehoods i expected the Manhunt book the most detailed and accurate description of the awful events to be portrayed in the film. The series would have benefited from your expertise

Great analysis Dave! I found myself picking out the inaccuracies, but I did enjoy the first episode for what it was: a good period drama piece. I thought the Lincoln deathbed scene was very moving. It truly must’ve been a gut wrenching and hopeless time waiting for the inevitable death of the president. Overall I liked the show and look forward to the next episode, but I still greatly enjoy getting wrapped up in the books by Swanson, Kauffman, Steers and Bogar.

I also found the scenes with Lincoln in the death chamber to be very poignant and moving. Even though the room where Lincoln died in the series is considerably larger than the famed “rubber room” of the actual Petersen House, the trauma of the loss is well conveyed in this episode.

Sounds like an insult to Mr. Swanson and his awesome book. Very disappointing.

I thought the episode was quite good, and most of what is listed above as errors is artistic license to keep the plot zipping along. As the review states, Stanton is our protagonist and POV character, so we see him basically being lead detective and doing stuff that the real Stanton didn’t do. It might have been better to show Booth and Harold stopping off at the Surratt tavern and meeting Lloyd, yes.

What jumped out at me was the scene showing John Surratt at Mudd’s house on April 15, talking about the assassination with Mudd. I’m no historian but from the books I’ve read Surratt avoided conviction for murder b/c he was able to produce a witness placing him in upstate New York on April 14. Wikipedia says he made it to Montreal by April 17 which he would have been hard-pressed to do if he’d been in Maryland on the night of April 15. I know that some details of the assassination remain mysterious, specifically the degree to which the Confederate Secret Service was involved with the plot, but is Surratt’s presence in Elmira, NY disputed?

Also the degree to which the series presents Stanton and Lincoln as friends startled me. I was under the impression that Stanton didn’t like Lincoln. And it’s established fact that Abraham Lincoln did not like to be called “Abe”. I guess they were trying to show that Stanton and Lincoln were friends which, fine, maybe they were by 1865, but they could have had Stanton calling him “Abraham.”

The scene between John Surratt and Dr. Mudd comes in the second episode of the series and you can be sure that I will be covering this fictitious scene in my next review. Likewise, I agree that the several instances of “Abe” in the second episode are off, given Lincoln’s known dislike of this nickname. I’m also not sure if William Seward went by the nickname “Bill” as Stanton calls him.

I tend to believe a number of the issues such as the absence of Powell’s horse and certain characters having expanded roles had to do with the series budget. The series Exec. Producer also was a writer for the third season of Fargo which opens each show with the tag line ‘This is a true story’ when all the Fargo series and the original movie are complete fiction. It may also be that to sign some recognizable names for the series, their roles had to be expanded.

To me, what is most telling is that I looked through the credits to see if the Historical Consultant / Advisor was a name I would recognize but no such position was listed. Given Dave’s list of errors as well as others not mentioned, it certainly appears the series had none, or if they did, that person did not want their name associated with the series.

I agree that certain production values show care was taken but if you remember the various Civil War era movies produced by Ted Turner, those scripts stayed much closer to the truth.

Dave you initially said that Herrold and Payne rode to Stantons home on one horse then subsequently left on separate horses. I enjoyed your review but did not see the first two episodes.

I’m sorry if that part of the review was confusing. The series shows Powell and Herold sharing a single horse as they arrive at the Seward home and then Davy escaping on it and leaving Powell high and dry when the deed is done. In real life, Powell has his own horse and he escaped on it after attacking the household. I hope this clears it up.

thanks for your comments- enjoyed reading them and am fascinated with the subject of the manhunt if Booth

Once again, Dave, you’ve hit a homerun. Your critique of “Manhunt” so far is masterful. Not only did you cover everything and note the main occasions of historic license and errors, your writing style is terrific. I am very impressed. I am also very grateful to you for taking the time to devote to this series. I’m sure that others are equally appreciative!

BTW, we’ll never know whether Stanton said “Ages” or “Angels” when Lincoln died. I’m getting a bit tired of the so-called controversy, with apologies to you and our mtual good friend Scott Schroeder.

You raise an interesting point about Parker that I don’t believe anyone else has ever raised: If John Parker was at his post when Booth arrived at the door to the box, “there is no reason why Parker would have prevented Booth from entering.” Good thinking, Dave! I don’t think Forbes knew who Booth was. Two witnesses testified that Booth showed him a card, and that whatever it was, it did the job. Others have guessed that it may have been a card from Sen. Hale. I agree with them, and I stick my neck out by speculating that Booth thought ahead and wrote upon the back of it “pease allow this man, John Wilkes Booth, to say hello to the president.” There’s more to the story, but we’ll never know. Forbes was never called to testify; Hale had a meeting with Presidet Johnson shortly thereafter. There was probably a cover-up to protect his daugter Lucy. (This is much more intriguing than whethr or not Stanton said “ages” or “angels.”)

I look forward to the rest of your critique!

Thanks for the kudos, Richard. We’ll definitely have more to talk about as the series goes on.

wow. I love this.

Thanks for your cogent review of the first episode. We felt much the same way about it on all the points you write about and are looking forward to the next episodes(and your reviews). I let most of the screenplay’s inventions slide, but the running gag of having various people tell Booth he looks shorter/smaller in person-really? Shorter than what, seen where? The movies that hadn’t been invented yet? On TV? What in the world was the writer thinking with that? As you point out, it’s a punching-down of Booth who, despicable as he proved himself to be, was at that moment a respected and famous member of a well known family, not the villain of history or some 1860s Oswaldian loser who’d glumly sit still for insults on his appearance. And anyway, wasn’t he a perfectly average height for the time? Oh well!

Dave, I watched the first two episodes and while I believe there is much to praise, I think overall you were very kind in your review. I quit taking notes on inaccuracies halfway through the second episode and tried to evaluate it simply as television, since that seems to be what the storytellers are focusing on. From that point of view, I wasn’t very impressed. It probably is more interesting to viewers unfamiliar with the history, but then that’s unfortunate because of the barge load of inaccuracies that you described. I didn’t really find it enjoyable until episode 2 when Patton Oswalt shows up as Lafayette Baker. The real Edwin Stanton is just as interesting a character as the real Lafayette Baker. No, the dyspeptic, abrupt and imperious Stanton wouldn’t be the sympathetic character that this tale demands. But if we are going to have Edwin Stanton as Sam Spade he should at least get to make a wisecrack once in a while.

If you don’t mind, I’ll point out a couple of other inaccuracies. Lincoln wasn’t in the telegraph office when the news of Lee’s surrender came in. He was still en route to the capital from City Point on the River Queen, and got the word from Stanton upon his arrival. Then it was Lincoln, not Stanton, who visited Seward with the news. (Rather than serving a sitting Seward with a drink, Lincoln supposedly laid beside the prone secretary on his sickbed – how do you not use that??)

As others have pointed out, the real story, as related by Swanson and others, would make a great series. Making Stanton’s support for the abolition of slavery and his sympathy for the freed slaves a major theme is commendable, but one could do that without so many inventions. There’s a lot of imagination in this telling of the story. It’s too bad the writers didn’t employ some imagination devising a means of using the facts more often.

Thanks for your minute attention to detail and your lucid explanation. I look forward to future reviews.

Right now, only Patton Oswalt’s performance is killing me. His air quotes was really annoying in episode 2. Then his “hear something, say something”. Anyhow, as a 7th grade history teacher I am absolutely loving watching the show with your guide right along side of it. Thanks so much!

The actor that is playing Stanton is really doing a great job…and I agree, Eckert is excellent as well. I really wish shows would hire people like you, or the author of Manhunt to give guidance–breaking the wrong leg is certainly unforgivable.

why has no one commented that the actor playing Lincoln is too short? Also his face is unlined, unlike Lincoln’s who always looked world weary. To me, the role was miscast. And changing Stanton’s famous line……😡 I frankly was very disappointed in the first episode and stopped watching it because of all the inaccuracies. For anyone with even a slight knowledge of the event, too much was poetic license was taken.

Hamish Linklater, the actor playing Lincoln, is actually listed at 6’3” or 6’4”. So it’s not that he’s too short, it’s that the other actors are too tall. I noticed it right away too, but then when I realized who it was, I knew that he was a fairly tall guy. So I looked it up.

Fantastic review!!! I am getting over being annoyed at the inaccuracies and enjoying it as entertainment. To your point, my husband wanted to learn more about John Parker and how Lincoln was (actually, wasn’t) guarded that night. (And he didn’t get too annoyed by my periodic “that’s not true!” exclamations.)

Your Forrest Gump analogy was positively genius! 🤣

Looking forward to reading your review of Episode 2. Thanks for the excellent insights!

Great Review Dave! I don’t have cable or streaming, so I’ll have to vicariously through your reviews — or wait for a cheap DVD release a few years from now.

Some of these changes seem understandable, others not. Especially stuff like banning the sale of horse feed or the Secretary of War Stanton personally finding the murder weapon, which is just typical Hollywood thinking the audience is stupid. They could just have a soldier hand Stanton the weapon saying it was found in the box – which would still be inaccurate (Gobright gave the weapon to Police Chief Richards after refusing an order from a military officer to turn it over) but at least it would be respecting the audience’s intelligence. However, not seeing the show maybe I’m imagining it coming off in the worst possible way in my head.

I’ve always suspected that Booth gave Forbes Senator Hale’s card which he somehow obtained while courting Lucy. A couple of days after the assassination George A. Townsend (aka “GATH”) published an article claiming Booth posed as a senator to gain access to the box. Now GATH wrote a lot of inaccurate stuff along with his accurate stuff as the events were unfolding. And this same article is wrong in a lot of places as well. But maybe GATH heard a garbled second-hand (or later) rumor about the card. Protecting Senator Hale’s reputation could explain why there was no testimony by Forbes recorded that night by Tanner (despite Forbes being the last person to interact with Booth prior to the assassination) or the card not being put into evidence.

Quick Movie Pitch idea: A Rashomon style movie of all the differing accounts of the assassination. Including all the people who claimed to have climbed up to the box alongside Dr. Taft! All the people who claimed to put coins over Lincoln’s eyes! All the random doctors who attended/observed Lincoln (including one who had been on the ballot as a Breckinridge elector in 1860)! Recreations of William Withers different accounts over the years!

Excellent review-looking forward to more. Something that bugged me was the “running gag” of men telling Booth he looks smaller “in person”. Smaller than what-how he looked in the movies that hadn’t been invented yet? On cabinet cards? This seemed ridiculous. Also, wasn’t Booth average height for the time? Hardly a shrimp. Thanks again for your writeups!

The score, as noted is indeed rather exceptional. Having just watched the first episode I found myself taken with the scene of Union soldiers carrying Lincoln’s casket out while rain pours and a mourning crowd gathers- but those pipes, wow. A Beautifully rendered “Amazing Grace” was an eloquent touch, and admittedly very moving. I am riveted.

Question: would down by the riverside have had the “study war no more” lyric? My impression was that this was a 20th century line?

Good job of listing the historical inaccuracies, although too much “credit” is given to moving the Stanton based story along for artistic reasons. Strayed too far from reality. If a Stanton-centric based story is to be done, do it based, at least loosely, on what Stanton actually did. This becomes “history” to the TV based public and it diminishes history.

And how come anyone in business is always evil.

Just wanted to say that I found your blog through a link that showrunner Monica Beletsky posted on X/Twitter. I’m enjoying Manhunt as a political thriller, kind of like CSI: Washington, D.C., and reading your more historically accurate take on the series.

In episode one, the series has Booth yell “The South is vindicated!” after shooting Lincoln To my knowledge, he never did so. His first vocal outburst was “semper sic tyrannis”, one the does portray.

Dave-

Knowing that Billy Withers never passed up an opportunity to tell his embellished tale right right up to his death, I want to be careful in documenting his his jacket came into the possession of the US Government museum at Ford’s Theatre. In my Oldroyd manuscript, I have the jacket going to the museum in the Petersen House via a personal pledge from Withers to Oldroyd. My passage reads, “Although Withers’ memory may have been faulty, he did his best to offer useful testimony for his friend’s (Oldroyd’s) book buoyed by proof in the form of an artifact for his museum. In a September 19, 1926, New York Times article titled “LINCOLN DEVOTEE ENDS LONG YEARS OF LABOR” by Virginia Pope. “Fortune and persistence helped Mr. Oldroyd. He has many anecdotes of the strange manor in which the relics fell Into his hands. Watchful waiting played a greater part than chance in many instances. When he asked William Withers, conductor of the orchestra at Ford’s Theatre, to give him the coat he wore when he obstructed for a brief second Booth’s exit from the wings, the coat on which may still be seen the slash made by the assassin’s knife. He replied: “Oh. you’ll get it as you do everything, but you will have to wait until I die.” It seems that Withers made good on his promise for when Billy passed away, he passed on the jacket to Oldroyd and his museum. That jacket is currently on display in the museum at Ford’s Theatre.” I want to be sure that is correct. If you have another avenue to point me towards for a different version, I would appreciate it. Your research is spot on and always accurate, so I would defer to you on this episode in particular.

Great fusion of tv review and history. Can’t wait for more.