“Some Photographs of Females”

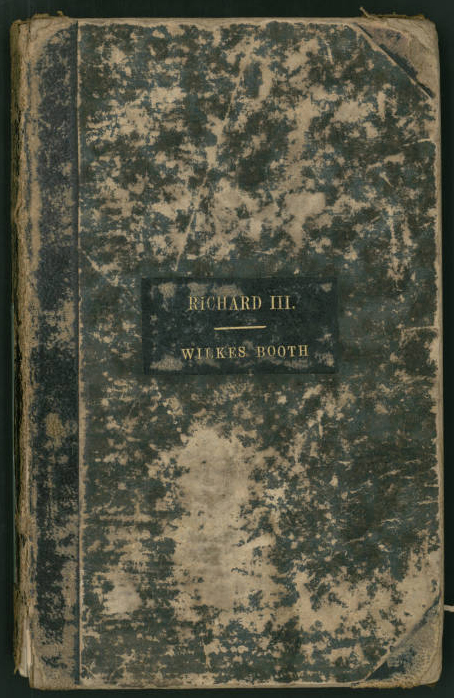

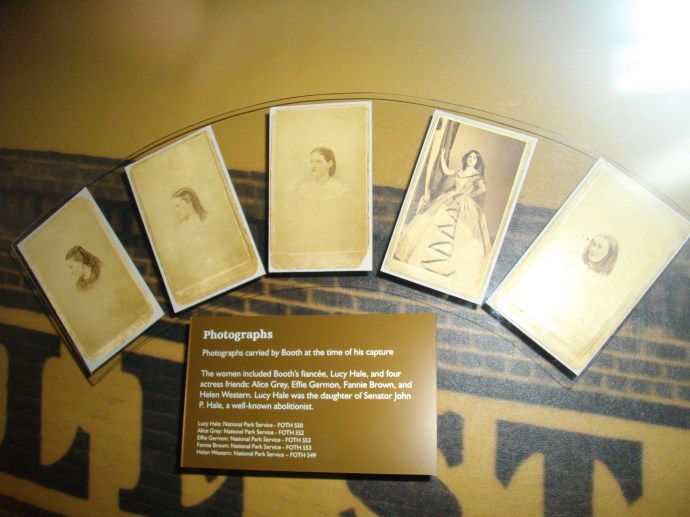

After John Wilkes Booth was shot and pulled from the Garretts’ burning tobacco barn, his body was subjected to a search. While the assassin of President Lincoln lay paralyzed and dying on the front porch of the Garrett farmhouse, the detectives rifled through his pockets, removing pieces of evidence. The items the detectives discovered worked to confirm his identity (which was never really in question), and give them the evidence they needed to prove back in Washington that Booth had, indeed, been taken. With reward money on their minds, such proof was of the utmost importance. Detective Everton Conger was so anxious to spread the news that Booth had been captured that he departed with some of Booth’s possessions before Booth had even died. One of the objects Conger brought back to Washington with him was Booth’s diary which contained the photographs of five ladies.

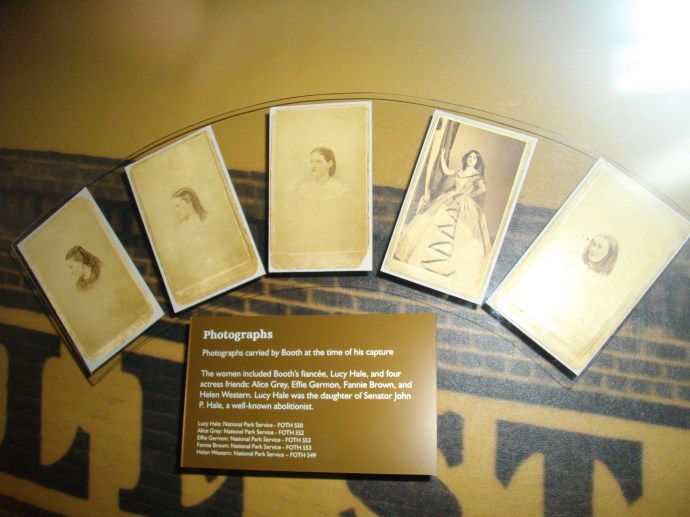

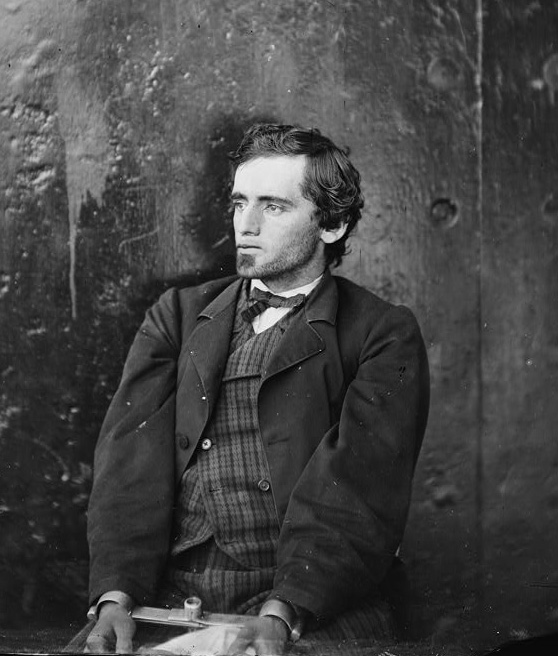

Historians Richard Sloan and Art Loux view the five photographs found on John Wilkes Booth’s body when he was killed. The man in the middle is former Ford’s Theatre curator Michael Harmon.

These images, like the diary itself, were turned over to the War Department where they languished for quite some time. Booth’s collection of ladies were deemed unimportant to the official investigation and were not used at the trial of the conspirators or at the 1867 trial of John Surratt. They eventually were boxed up along with some other evidence used at the trial and Booth’s other possessions. They were stored with the War Department files in the Judge Advocate General’s Office.

It was quite some time before the existence of these photographs became known to the general public. When the text of John Wilkes Booth’s diary was published for the first time in 1867, the affidavit attached to it from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton stated that only the quoted entries and “some photographs of females” comprised the contents of the diary. There appears to have been no follow up or inquiry about who these females were or why Booth had their photographs in his diary. It wasn’t until several years later, when the occasional newspaper reporter convinced the Judge Advocate General’s Office to let them take a peak at the relics of the assassination, that any discussion of the photographs began.

An inquisitive reporter with the Cleveland Herald visited the relics in the JAG office in 1884. Entranced with the more vivid relics such as Booth’s derringer and pieces of Lincoln’s skull, the reporter only made a passing mention of the ladies in Booth’s diary. He stated, “among the articles found in the ‘pocket’ of the book are five photographs of young women, presumably actresses.” It appears that the identities of the ladies in Booth’s pocket had not been researched much prior to this, seeing as this reporter was given no information about who they were.

Visitors to see the relics were relatively scarce and those who were able to view the artifacts could only do so with advance permission from either the Secretary of War or Judge Advocate General. The artifacts were viewed by “about three or four people a year,” considerably slowing down the process of identifying the ladies. It was essentially left to the few clerks who acted as custodians over the relics to attempt to identify them, which they did with varying degrees of success.

Effie Germon and Lucy Hale

It appears that the identity of two of the ladies contained in Booth’s diary were identified a bit earlier than the rest. A reporter who was given access to view the relics in 1891 was correctly told that two of the images in the set were of actress Effie Germon and of “a daughter of one distinguished Senator from a New England state.”

Effie Germon

Lucy Hale

On the night of Lincoln’s assassination, Effie Germon was performing the lead of Aladdin at Grover’s Theatre in D.C. In the audience was young Tad Lincoln, who heard the news of his father’s assassination when the play at Grover’s was halted to announce the tragedy. The 1891 reporter was kind in describing the image Booth possessed of this easily recognizable star of the stage, “Miss Effie Germon, once leading lady at Wallack’s, is one. It is a fair young face, strikingly beautiful.” However the reporter is not so kind when he relates Ms. Germon’s current state, “Miss Germon, if living, is now an old woman, and they say she is fat.”

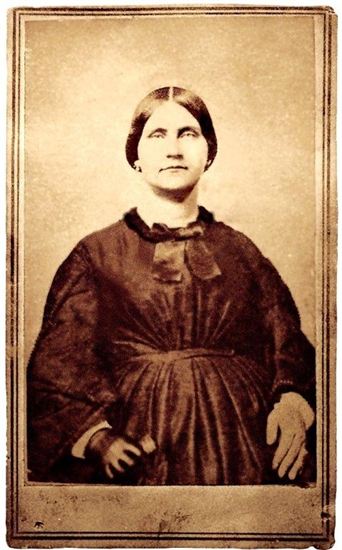

Lucy Hale was the daughter of U.S. Senator John Parker Hale of New Hampshire. She was also John Wilkes Booth’s secret fiancée. The main evidence for believing that Booth and Lucy were actually in love is not only the collections of the Booth family who supported the idea of an engagement but also from Booth’s own words. Some of Booth’s final thoughts were of Lucy and this is demonstrated in his diary.

It is largely forgotten or ignored that the very first words written in Booth’s diary are “Ti Amo.” “Ti Amo” is Italian but seems to be an understandable misspelling of the Spanish “Te Amo.” Regardless, both translate into English as “I love you”. This announcement of love, coded a bit, seems out of place in Booth’s diary. Before starting his manifesto about why he shot the President, John Wilkes Booth was compelled to write a brief note of love to someone. It seems likely that this message was meant for Lucy Hale.

Prior to the assassination, Lucy’s father, Senator Hale, had been appointed as a minister to Spain. All of the Hales were in earnest to learn some Spanish before heading abroad with their father. Lucy vowed to John Wilkes that she would return in a year, with or without her father’s permission, in order to marry him. Lucy lived in the same Washington hotel as Booth, and he would have almost assuredly witnessed his fiancée practicing Spanish.

It may be a romantic idea, but it’s possible that the Ti Amo in Booth’s diary was his final message to the woman he loved. It was a message Lucy would know was meant for her and for no one else. It was a way for him to announce his love for her, for the last time, without endangering her further.

What would have become of Booth and Lucy’s relationship had he not assassinated the President is unknown. Perhaps it was always doomed to fail due to Booth’s womanizing as evidenced by his diary’s collection of other beautiful women. Still, the presence of Lucy’s image and the coded “I love you” message in Booth’s diary could easily demonstrate that, in his final days on the run, John Wilkes Booth thought of, and loved, Lucy.

Mistakes and Misidentifications

Though it was correctly concluded that Effie Germon and Lucy Hale were among those represented in Booth’s photographs, this did not mean that they were always identified correctly. In 1891, a reporter was shown the relics by a clerk of the Judge Advocate General’s office named Mr. Saxton. You can read the reporter’s article about the visit by clicking this line. Unfortunately, Mr. Saxton appears to have been all mixed up when it came to which image was of which woman. In addition, he provided incorrect identifications for the rest of the images and only seemed to show the reporter four out of the five images.

Mr. Saxton’s mistakes and misidentifications, which demonstrate the JAG office’s lingering uncertainty about who these women were, are as follows:

Actress Alice Grey was mistaken for fellow actress Effie Germon:

Effie Germon

Alice Gray

Lucy Hale was misidentified as a singer named Caroline Richings:

Lucy Hale

Caroline Richings

Actress Helen Western was mistaken for actress Olive Logan by the reporter before Mr. Saxton misidentified her as Lucy Hale:

Helen Western

Olive Logan

Lucy Hale

And actress Effie Germon was mistaken for another actress named Rose Eytinge:

Effie Germon

Rose Eytinge

While we may laugh today about the numerous mistakes in Mr. Saxton’s 1891 identifications, it does demonstrate that there was somewhat of an attempt by someone in the JAG office to learn the identities of these women. This leads us to the last image in the set photographs and the case of John Wilkes Booth’s “Mysterious Beauty”.

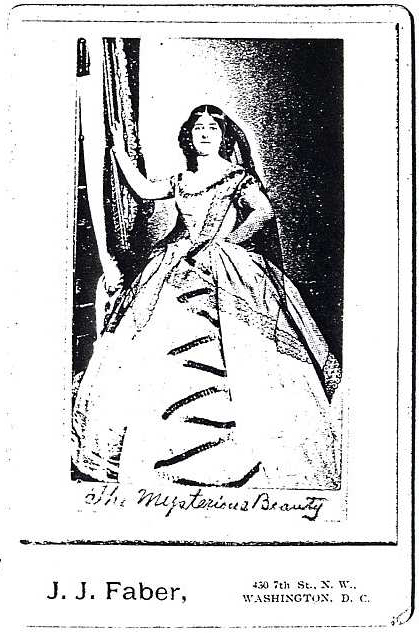

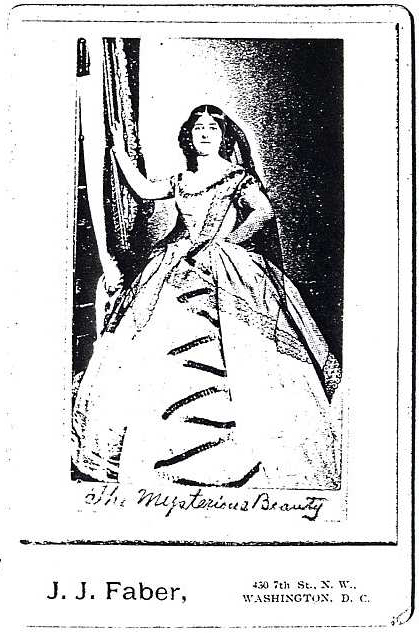

“The Mysterious Beauty”

We know that, eventually, the first four vignetted photographs were correctly identified as Alice Grey, Effie Germon, Helen Western and Lucy Hale. It is likely that the clerks of the JAG office consulted a few more visitors who possessed far better knowledge about the theatrical leading ladies of the 1860’s and that they helped fix the mistakes. However, even after four out of the five women were identified, the identity of the woman in the last image was still uncertain. This woman, her image different from the rest in that it showed her full body rather than just a vignette of her face, was still unknown. A more active search was undertaken to learn who she was.

As has been demonstrated by other images of artifacts in possession of the Judge Advocate General’s office (this one for example), the items relating to Lincoln’s assassination were not always treated with the same degree of preservation or care as they receive today. Some of the smaller pieces found on Booth’s body mysteriously disappeared over the years, such as a small horseshoe charm, a diamond stick pin, and a Catholic medallion. In addition to these losses, the clerks at the JAG office even burned some of the clothing collected as evidence when moths began to eat away at it. Modern museum curators would cringe at the way in which these artifacts were locked up in a box with no thought of temperature or humidity.

It is therefore unsurprising that the images of Booth’s ladies would also be subjected to neglect or ignorant mistreatment. Such was the case when one of the custodians of the artifacts decided he really wanted to know the identity of the woman in the standing photo. Until she was recognized, some unnamed clerk nicknamed her “The Mysterious Beauty” and went so far as to write that moniker on the bottom of the original image itself.

One must remember that the entire collection of assassination related artifacts stored by the Judge Advocate General’s office was still considered to be official evidence and property of the U.S. government. In the years after the assassination, several organizations had tried, and failed, to gain ownership of the artifacts. There were even efforts by various Judge Advocate Generals to rid themselves of the pesky items that garnered such macabre interest. The items were almost transferred to the Smithsonian before the Judge Advocate General’s office declared that even if they were transferred to the Smithsonian, the government would still own them and the Smithsonian essentially couldn’t do anything with them other than store them. After that, the Smithsonian was no longer interested.

With this in mind, it is amazing to picture a clerk of the Judge Advocate General’s office causally taking this CDV, a piece of government owned evidence that even the Smithsonian couldn’t be trusted with, out of the JAG office and into the Washington streets. The clerk walked to the nearby photography studio of J.J. Faber and had the photographer duplicate the image with “The Mysterious Beauty” inscription onto larger format images known as cabinet cards. A photocopy of one of the cabinet cards is pictured above. How many copies were made of this image is unknown, but it is likely that the unnamed clerk made enough copies to pass around. The original, defaced, image was subsequently returned to its governmental prison.

How long it took to correctly identify this beauty after her image was duplicated and passed around, or who eventually made the correct identification, is not known, but eventually the unnamed clerk’s effort paid off. On the back of the photocopied cabinet card pictured above (which was sent to author Francis Wilson in the 1910’s – 1920’s as he was working on his book about John Wilkes Booth), the following statement was recorded:

“The original of this picture was found, after his death, in the diary of John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Lincoln. It was not known for a long time who the subject of the picture was and the custodian of the ‘Booth diary’ and other articles connected with the great tragedy, stored in the archives of the War Department, had some copies made of it for the purpose of identification. It was finally recognized as being the picture of Fanny Brow, an actress who died many years ago. Since that time the words “The Mysterious Beauty” have been effaced from the original in the War Department.

War Department

Office of the Judge Advocate General

John P. Simonton

Custodian”

Indeed, this final image was determined to be that of actress Fanny Brown.

Revealed at last, John Wilkes Booth’s “Mysterious Beauty” was Fanny Brown.

Fanny Brown had known John Wilkes Booth since at least 1863 when they performed together throughout cities in New England. Gossip of the day even hinted at a romantic relationship between the pair, which would not be surprising given Booth’s established success in wooing women:

As clerk John Simonton* states, after Fanny Brown’s identity was established, the words “The Mysterious Beauty” were erased from the original image. However, as any museum curator will tell you, alterations to an artifact can never truly be erased. A close inspection of the bottom of Fanny Brown’s CDV shows the faint outline of the words that were once carelessly scribbled onto her gift to John Wilkes Booth:

A Fitting Repose

Eventually Alice Grey, Effie Germon, Helen Western, Lucy Hale, and Fanny Brown escaped their prison in the Judge Advocate General’s office. On February 5, 1940, the artifact evidence held by the JAG was officially transferred to the Lincoln Museum, also known as Ford’s Theatre. In the years since then, the ladies have spent some on display but still spent more time in a couple of National Park Service storage facilities. Today, however, all five of these beauties are on display in the assassination section of the Ford’s Theatre Museum.

After so many years of being confined to a box, ignored, misidentified, and forgotten, it’s great to see these ladies on display so prominently at Ford’s Theatre. Their innocent beauty is a much needed contrast to the dark tools of the assassination that surround them. These images of Lucy Hale, Alice Grey, Effie Germon, Fanny Brown, and Helen Western perfectly represent the beautiful life that John Wilkes Booth mysteriously threw away when he committed his violent act of hate on April 14, 1865.

References:

Denver Rocky Mountain News, January 13, 1884 (republishes the article from the Cleveland Herald)

“Relics of a Tragedy”, The World, April, 26, 1891

The Richard and Kellie Gutman Collection

The Art Loux Archive

Ford’s Theatre Museum

Library of Congress

New York Public Library

*John Paul Simonton, the clerk who wrote the note on the back of the cabinet card explaining the story of “The Mysterious Beauty” is occasionally referenced by those who believe John Wilkes Booth was not killed on April 26, 1865. Simonton worked as a law clerk in the JAG office from 1877 – 1920. After his retirement, he wrote an affidavit in 1925 stating, in part, “I studied the evidence in this case and examined all the exhibits as an expert and found no definite proof that John Wilkes Booth was ever captured. The fact that John Wilkes Booth was captured could not be established before any court in the United States on the evidence submitted at the time of the trial and now on file at the War Department.” Conspiracy theorists use this as “proof” that Booth escaped. Interestingly, they largely ignore an 1898 letter from Simonton to Finis Bates (of the Booth mummy story) in which Simonton stated, “While I have not what may be styled direct or positive evidence that the man killed was Booth, I have such circumstantial evidence as would seem to prove the fact beyond doubt.” In addition, Simonton clearly states on the back of this cabinet card that “this picture was found, after his death, in the diary of John Wilkes Booth,” solidifying that it was his firm opinion that it was John Wilkes Booth who was killed. When it comes to his 1925 statement, Simonton is very clearly pointing out the fact of Booth’s death was not definitely proven at the trial of the conspirators and in this he would be correct. The object of the trial of the conspirators was not to conclusively prove that Booth was dead, it was was to try the conspirators for their involvement in Lincoln’s death. The files and evidence of the conspiracy trial do not definitely or directly prove Booth’s death as this was not the objective of the trial. However, evidence from sources outside the conspiracy trial (i.e. autopsy reports, the numerous identification of Booth’s body by his friends and family, official statements from David Herold, the Garrett family, the troopers that captured him, etc.) along with the circumstantial evidence presented at the conspiracy trial (i.e. Booth’s possessions taken from him after he was shot) do conclusively prove that Booth was killed.

Recent Comments