The first two episodes of the miniseries Manhunt, based on the book by James L. Swanson, were released on AppleTV+ on March 15, 2024. This is a historical review of the second episode, “Post-mortem.” If you want to avoid spoilers, I suggest you wait to read this review until after you have had a chance to watch this episode. If you would like to read the review for the prior episode, “Pilot,” click here.

Episode 2: Post-mortem

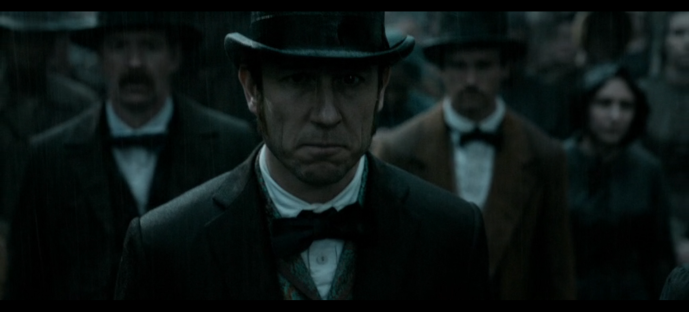

In the second episode of Manhunt, we see our hero, Edwin Stanton, plagued by guilt over the death of Lincoln and desperate to catch the assassin before he escapes too far. The Secretary of War calls in others to help, but he is still everywhere in this episode. The new President, Andrew Johnson, is sworn in and makes his priorities for the nation clear. Also, in Washington, preparations are made for Lincoln’s body to be transported to Springfield, Illinois, on a whistle-stop tour of the grieving nation. Meanwhile, in Charles County, Maryland, John Wilkes Booth and David Herold finish their time at Dr. Mudd’s and meet up with Oswell Swann, who reluctantly agrees to act as their guide to Rich Hill. Also in this episode, we see the arrests of Lewis Powell and Mary Surratt, as well as some flashbacks involving the early life of Mary Simms and David Herold’s recruitment into the plot. John Surratt, Jr. makes his first appearance in the series, both in flashback form and in the timeline of the main story.

There’s a lot of fact vs fiction to unpack in this episode. But before moving on to that, here are some things that I enjoyed about this second episode:

- Andrew Johnson

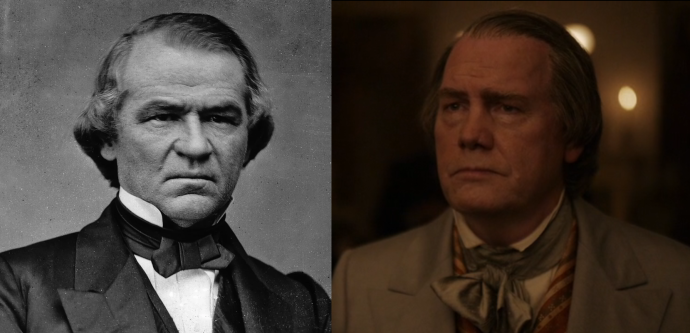

From the first time we meet him, it’s clear that this series is going to have more than one villain. The adversarial relationship between Stanton and Johnson is evident from the moment the Secretary of War enters Johnson’s room. Their icy retorts to each other are well-acted and hint at the action that later snowballed into Johnson’s impeachment – the suspension and firing of Stanton in 1867/68. From the start, Johnson is slimy and unpleasant…and I love it. Of course, the series is exaggerating a lot of the Johnson stuff. In particular, the idea that Johnson, on the same day as Lincoln’s death, would come anywhere close to saying that the country should just forget it and move on is ludicrous. He mourned Lincoln as much as anyone and was just as eager for vengeance on the assassins as Stanton. Remember, he’s the one who ignored the clemency plea for Mary Surratt and let her hang. But, while his quest to avenge Lincoln was strong, the rest of his Presidency was poor. Johnson was an obstinate and petty President who gave up on the Freedmen just when Black Americans needed a strong supporter the most. There’s a reason why Johnson is almost always at the bottom of Presidential rankings, right alongside James Buchanan, who did nothing to prevent the Civil War, and Trump, who tried to overthrow our democracy.

In Manhunt, Actor Glenn Morshower gives a great performance as Johnson, complete with a good Southern drawl for the North Carolinian turned Tennessean. I also have to give great props to the series’ makeup team for transforming Morshower into the spitting image of the 17th President. While our beardless Stanton may not look much like the real McCoy, his adversaries, Booth and Johnson, are well done.

I’m looking forward to seeing more of Johnson and his inevitable machinations in the episodes that follow.

- The Theme Song and Credits

I praised the music in my last review as well, but in this episode, we get to hear the theme song as intended during the complete opening credits. The theme song is called Egún by Danielle Ponder. Even if you haven’t watched (or aren’t going to watch) the series, you should still check out this song. You can listen to it on Spotify and Apple Music, but if you don’t have one of those services, here’s a YouTube video with the song.

YouTube has weird copyright rules regarding music, so I don’t know how long this video of the song will stay up. But give it a listen if you can.

The theme is even better in context with the opening credits, which we see for the first time in this episode. Various period images act as the background with a variety of effects. Some images act like wet plate photographs, transforming from negatives to positives before your eyes. Others become scratched or decay. Most have an effect like liquid or ice on the surface. The most compelling part of the credits shows the deathbed of Lincoln, and a pool of red blood slowly appears and grows on the pillows.

Watching this part of the credits inspired me to go back to Episode 1 and look more closely at the bed Lincoln died in at the Petersen House. It’s a little blurry in the stylized credits image, but the production did source a great lookalike bed. Their bed looks strikingly like the real bed in the Chicago History Museum. Replicating Willie Clark’s bed so closely shows great attention to detail on the part of the set dressers.

In addition to the main theme, this episode has a really catchy end-credit song that I haven’t gotten out of my head since I first heard it in the trailer for the series. It’s not on the official series soundtrack, probably because they are just licensing the song for inclusion in the show. By searching for the lyrics, I was able to find it. The song is called Devil’s Spoke, and it is performed by Laura Marling. It’s a real banger. Here’s the music video:

Both songs make for a great beginning and end to an episode, and I hope Devil’s Spoke is included in all the rest of the episodes that come.

- Shaving Booth

You might be surprised to learn that, despite it being nothing but a fictional flight of fancy on the part of the writers, I actually enjoyed the scene where Mary Simms attempts to shave John Wilkes Booth at the Mudd farm. This scene demonstrated Booth’s racism well, and the acting between Anthony Boyle and Lovie Simone was filled with genuine dramatic tension. As Simms brings the razor close to his face, the arrogant Booth realizes that he is not in the dominant position at the moment and is fearful that Mary might give back to him what he is owed. While her drawing blood is accidental, Booth’s rage is not, as he has to work hard to re-establish his own dominance. He threatens Mary, and she does flee, but he is the one left bleeding.

Watching Mary Simms sharpen that blade, it’s hard not to cheer for her to pull an Inglourious Basterds and take Booth out. It reminded me of the many “close calls” Booth experienced in his life, any one of which could have led to his death and thus saved Lincoln. Had the bullet from Matthew Canning’s gun just nicked Booth’s femoral artery when the young actor was accidentally shot in 1860, the course of American history would have changed forever.

As much as I enjoy this fictional shaving scene for the dramatic tension, I will point out that there was a noticeable continuity error here. As Booth grabs Simms’s hand after being cut and holds it close to her face, there’s clearly little to no shaving cream on the blade.

Yet, when he pushes the razor up to her lips, suddenly, there’s a lot of shaving cream that gets transferred onto Mary Simms’s mouth.

I doubt I was the only person to notice this during my first watch-through. Still, it doesn’t detract too much from the effect of the scene.

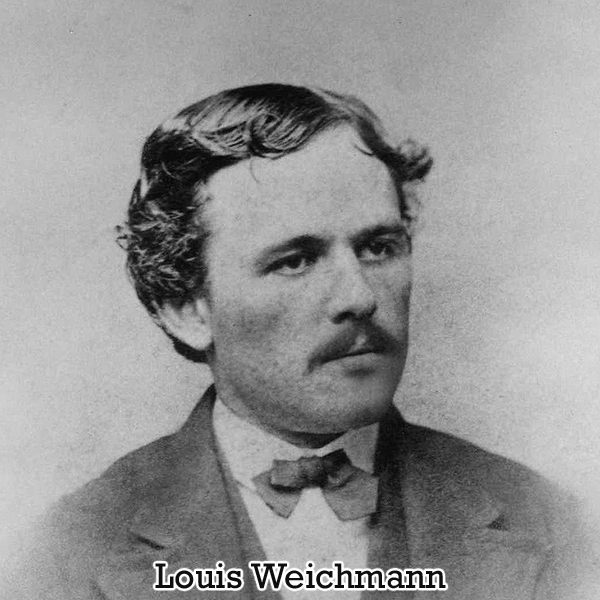

- Interrogating Louis Weichmann

In the first episode, we only caught a glimpse of actor C.J. Hoff in the role of Mary Surratt’s boarder, Louis Weichmann, as he looked suspiciously at the departing Lewis Powell (who had not actually stayed at the Surratt boardinghouse since March 17). In Episode 2, Weichmann has more of a role, first telling Stanton of his landlady’s possible connection to the plot and, later, escorting Stanton and Eckert down to Mrs. Surratt’s tavern in Maryland. We’ll cover all the things wrong with that imaginary event later, but I did find myself enjoying Hoff’s portrayal of Weichmann as Stanton and Eckert started laying into him about what he knows.

Weichmann comes across as scared and way over his head in trying to explain to his boss how he could have lived amongst people plotting against the President. When Stanton gets more forceful in his accusations, Weichmann deflects to Mrs. Surratt. This interrogation plays out much like I would imagine Weichmann’s first initial interviews actually went. Hoff is playing the role of the somewhat sympathics but also somewhat weasely Weichmann well. I’m looking forward to seeing more.

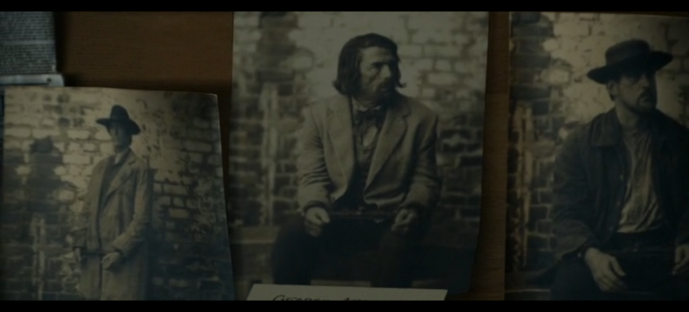

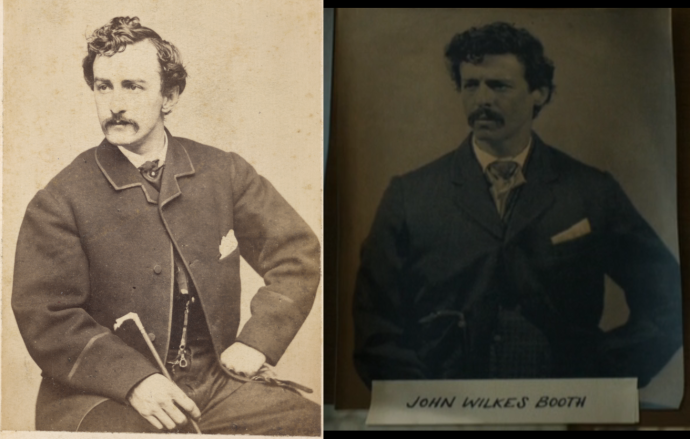

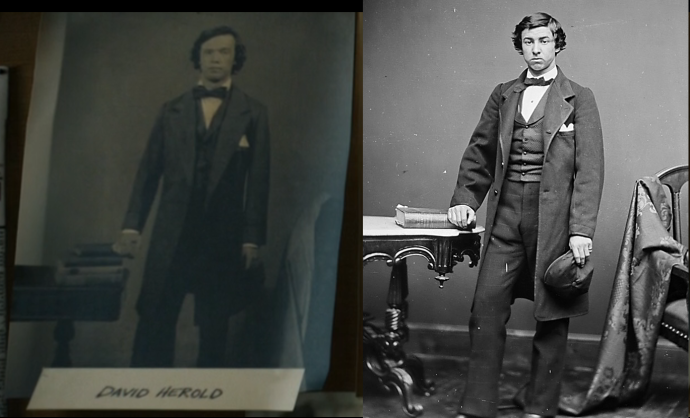

- Recreated photographs

On Stanton’s bulletin board in the War Department, there are several pictures connected to the conspirators. There are photographs of George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell, and Edman Spangler, who are all in custody on April 15th in the series’ fictional timeline. Each of these men is wearing lily iron handcuffs and replicating the mugshots of their real-life counterparts. These recreations aren’t perfect, and the background is a brick wall rather than the distinctive black gun turret of the USS Saugus, where the seated images of these men were actually taken. But it’s clear attention has been paid.

While these images are decent recreations of the originals, where the series has done a better job has been replicating the images of David Herold and Booth that were subsequently used on the wanted posters. Boyle’s Booth is holding a cane just like the real image, and the photo of a young David Herold has been very closely matched.

Like the closely matching deathbed, I appreciate this attention to detail.

Those were some of my favorite parts of “Post-mortem.” Now, let’s start breaking down the instances of dramatic license and historical inaccuracies present in this second episode.

1. Edwin Stanton and the Longest Day Ever

I tell you, our poor hero needs a break. The man has been running around nonstop in these first two episodes. April 15th, in particular, was the day that just would not end for our main man. Allow me to recap everything that the first and second episodes have shown Edwin Stanton doing on April 15, 1865.

- He is present at the Petersen House all during the early morning hours after having arrived there late on April 14th.

- At 7:22 am, he mournfully cries at the death of the President.

- Eddie, Jr. brings a casket to the Petersen House, and Stanton takes part in a rainy funerary march with Lincoln’s coffin (likely back to the White House).

- He returns to Ford’s Theatre after the funerary march. The rain has now stopped.

- At Ford’s, Stanton acquires a photograph of Booth, is briefly interviewed by Sandford Conover, examines the President’s box, and interviews Peanut John.

- He waits for Edman Spangler outside of Ford’s and has him arrested.

- He visits the Petersen House as it is being photographed and talks to Conover again. Upon leaving the Petersen House, he yells at a man on the street hawking relics.

- He heads over to the National Hotel and searches the Booth’s room with Eckert.

- He makes his way back to the War Department and takes a much-needed nap, dreaming he is trying to stop Booth from shooting the President. This dream sequence of Stanton fighting with Booth reminded me of the scene from an animated Batman cartoon where the caped crusader takes on a mechanized John Wilkes Boom.

- He interviews the liveryman who rented Booth and Herold their horses.

- Louis Weichmann briefly talks to Stanton while he’s leaving the War Department. Luckily, he delegates going to the Surratt boardinghouse to Eckert.

- Instead of going to Mary Surratt’s, Stanton goes to the Kirkwood House and wakes up Andrew Johnson.

- He is present as Johnson is sworn in as the 17th President. His busy day so far has caused him to miss going to the cemetery to visit his dead son’s grave. Luckily, Mrs. Stanton understands.

- Stanton goes to the White House, where he chats with Elizabeth Keckley and Mrs. Lincoln about what disposition should be made of the President’s body.

- He returns to the War Department, where Col. Lafayette Baker has arrived from New York City after being summoned earlier that day (fast travel in those days, I guess).

- Eddie, Jr. has gained information on John Surratt, Jr. Eddie states that the Surratt Tavern in Maryland has been searched but nothing was found. Stanton decides he needs to search it, personally.

- He rides down to Surrattsville, Maryland, with Eckert and Weichmann in tow.

- Using his spidey-sense, Stanton finds a secret room in the Surratt Tavern with spy stuff in it, including a coded telegram.

- He returns to Washington and visits Mary Surratt and the male conspirators in prison. He interrogates them about where John Surratt and Booth are.

- He goes back to the War Department, unhappy that Eckert has not already deciphered the telegram they just found with the code they also just found that day.

- Peanut John visits the War Department, having failed to tell Stanton earlier that day that Booth looked like he had a broken leg. Stanton sends Luther Baker (who, like his cousin Layfette Baker, has teleported down from NYC) to the Mudd house to question him.

- Eddie, Jr. shows his dad a photograph of Lincoln’s second inaugural with Booth in it

- Sundown has finally come, and Stanton goes to a party at the White House in Johnson’s honor.

- He chats with Elizabeth Keckley at the party and laments that his department just missed catching Booth at Dr. Mudd’s house.

- Meanwhile, at the Stanton home (which he hasn’t apparently been to for about 24 hours now), a shadowy figure skulks around, scaring Mrs. Stanton.

- He returns to the War Department after the White House party, and Eckert is still hard at work deciphering. Eddie, Jr. reports that footprints have been found at his home. Stanton asks for John Surratt’s shoe size from the files (what a detailed clerkship application he must have filled out!)

- Stanton acquires a pair of shoes in John Surratt’s size and plays Sherlock Holmes, matching them to the footprints outside his house.

That, ladies and gentlemen, was Edwin Stanton’s Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad (and Endless) Day on April 15, 1865. Of course, I completely understand that the timeline of things needs to be accelerated as the miniseries only has 7 hours to tell the whole story it wants to tell. Still, I thought it might be interesting to see what the real Stanton did on April 15.

I know Edwin Booth better than I know Edwin Stanton, so I consulted Walter Stahr’s 2017 book, Stanton: Lincoln’s War Secretary, for a breakdown of his movements on that fateful day. A lot of the initial activities the series shows Stanton doing are correct. He was present at the Petersen House during the entirety of the death watch over President Lincoln. During that time, he was largely in the front parlor, sending out telegrams to the military authorities, starting the search for the assassins, as well as listening to eyewitness statements. When the President’s heart rate began to fall, and his breathing slowed, Stanton returned to the small back bedroom and witnessed Lincoln’s final gasps. He then spoke his iconic lines (or didn’t). After Lincoln’s death, the Cabinet members present in the Petersen House had an impromptu meeting, and they sent a formal notice to Vice President Johnson informing him that he needed to take the oath of office. While Johnson had visited the Petersen House during the deathwatch, he did not stay like other members of the cabinet. This retreat was likely out of respect for the mourning Mrs. Lincoln or perhaps the order of Stanton himself, not wanting the Vice President to be a target.

As is shown in the series, Stanton stays at the Petersen House with Lincoln’s body for a time until a casket is secured and brought. He oversees as the President’s body is wrapped in an American flag and loaded into the plain pine coffin. Stanton did take part in the slow funeral march following Lincoln’s wagon to the White House as shown in episode 1.

According to Stahr’s book, Stanton was not present when Johnson took the oath of office during the morning hours on April 15th. He posits that the Secretary was in the telegraph office sending messages to General Sherman and the American minister in London about the death of Lincoln. By noon, however, Stanton was at the Treasury Building and taking part in his first cabinet meeting with the new Commander-in-Chief. Johnson informed the men that he would do his best to follow the same policy as his predecessor (that commitment wouldn’t last long) and that he wanted them all to stay on in their positions. According to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, the new President “deported himself admirably” during this first meeting. At this point, everyone was on the same page: keep the country going and find the people responsible for this great crime.

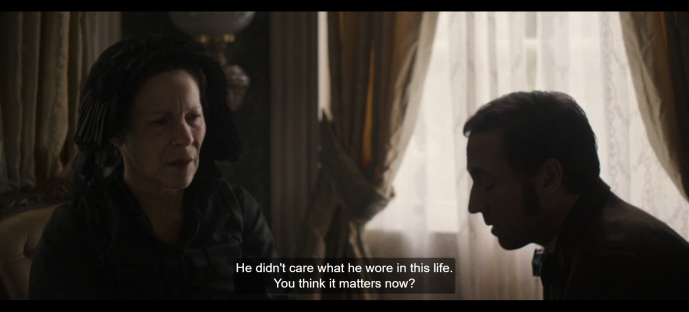

During these hours, an autopsy was performed on Lincoln at the White House. After this was completed, his body was embalmed and cleaned. At some point after his cabinet meeting with Johnson, Stanton went to the White House and supervised the dressing of the President’s body. The series hints at this event in the scene where Stanton speaks with Mrs. Lincoln and asks her what she wants him buried in.

The only other things Stahr has Stanton doing on this day are sending out messages to Henry Steel Olcott and Lafayette Baker in New York, requesting their presence in D.C. to help with the investigation. Already, he was looking for trusted men to whom he could delegate the hunt for the assassins. The fifty-year-old Stanton was likely exhausted by his real labors on April 15th and went home to sleep. When the cabinet met at ten o’clock the next day, Sunday, April 16, Secretary Welles noted that Stanton was “more than an hour late.” You have to give credit to Tobias Menzies’s Stanton for doing everything the real guy did and so much more, and still managing to stay on his feet.

2. The Arrests of Lewis Powell and Mary Surratt

One of the events shown on this very long April 15 is the arrest of both Lewis Powell and Mary Surratt. In reality, the arrests of these two conspirators did not happen until very late in the evening of April 17. Again, I’m not too upset with the incorrect timeline because this is undoubtedly an example of where the producers had to accelerate some events in order to keep things moving.

In this episode, Thomas Eckert (still one of my favorite characters) heads to the Surratt boardinghouse with Louis Weichmann to interview Mrs. Surratt. She admits to knowing Booth and having given him “cooking utensils.” During their interview, a knock comes at the door, and Eckert orders Mary to answer it. When she does, a beleaguered-looking Powell, wearing a shirt on his head and carrying a pickax, walks in, saying he didn’t know where else to go. Mrs. Surratt tries her best to get rid of him, but Eckert is immediately curious and asks Powell why he is there. He claims to be a laborer hired to dig a gutter, but Mary immediately undercuts him by saying she’s never seen the man before in her life. Weichmann points out the bloody coat, leading Powell to attempt to seize the pickax. Eckert is on him quickly and prevents Powell from fully brandishing the makeshift weapon. After some grappling on the floor, Eckert pulls his gun and points it at Powell’s face. This ends their scuffle. During the commotion, Mary had made a brief attempt to flee but stopped at Weichmann’s command and the drawing of his pistol. Mrs. Surratt falls to the ground in prayer as Eckert gets his own CSI Miami “Puts on Sunglasses” type moment with the line, “Now look at that. You did dig a hole together.”

I give the scene style points for adding a little fight between Eckert and Powell, but when it comes to the actual details of Powell’s arrival at the Surratt boardinghouse and his arrest, we’re a bit off course.

One of the great unknowns in the story of Lincoln’s death is where the tip connecting John Wilkes Booth to John Surratt in the immediate aftermath of the crime came from. The exact source is never recorded, but about four hours after the shooting, General Augur, who commanded the defenses of Washington, sent detectives to the Surratt boardinghouse on H Street to search for John Surratt. The household was largely asleep and had not yet heard about the assassination. The detectives interrogated the household, including Louis Weichmann and Mrs. Surratt, about the whereabouts of John Surratt. Both stated that he hadn’t been in the city in about two weeks. After searching the place, the detectives left, and Weichmann was left to mull over the news that Booth had shot the President and that his friend and landlady may have been involved. The next morning, Weichmann read more of the details in the paper and had breakfast at the boardinghouse. Reading about the attack on Seward’s home, he knew he had to get ahead of this thing he was partially wrapped up in. Instead of going to Stanton or the War Department where he worked, Weichmann went to the D.C. Metropolitan Police and started telling them about the various visitors to Mrs. Surratt’s boardinghouse, including Atzerodt, “Payne,” and Booth.

Rather than being arrested and held as a possible coconspirator, Weichmann was pressed into service as a detective, helping to track the assassins down. In his memoirs, he claimed to have traveled with other detectives to the home of David Herold near the Navy Yard and procured Davy’s image from his mother. He also states that he and others rode horses down into Maryland along the same road Booth and Herold took. They scoured the area on the way to Surrattsville with no success. So, the idea of Weichmann acting as a guide to the Surratt Tavern, as shown in the series, has some factual basis. Having not found Booth (he was still resting at the Mudd house at this point), the men returned to D.C., where Weichmann slept in the police station. The next morning, April 16, Weichmann and a posse of detectives traveled to Baltimore under a tip that Atzerodt might be found there. They spent all day in Baltimore but did not find anything helpful, so they returned to Washington. The next day, April 17, Weichmann was authorized by Gen. Augur to join a group of detectives heading for Canada in search of John Surratt. They left that day, and Weichmann would spend several days in Montreal, hot on the trail of Surratt, before being ultimately ordered by Edwin Stanton back to Washington. Stanton was furious that an important witness (and possible conspirator) had been allowed to leave the country. In this way, we see that the real Weichmann was not around for the arrest of Lewis Powell and Mary Surratt on the night of April 17. He was on his way up to Canada with a posse of detectives at the time.

By April 17, the authorities had heard enough about the past happenings at the boardinghouse to know that they needed to bring the entire household in for questioning. A squad of detectives arrived that night and informed Mrs. Surratt and all of her boarders that they were being taken in. It was while the detectives were waiting for a coach to carry all the women away that Lewis Powell made his incredibly ill-timed arrival. It was a detective, not Mrs. Surratt, who answered the door and, in this way, Powell found himself trapped. The detectives asked him the same question we see Eckert ask, along with a few more about his life as a “laborer.” Powell was somewhat differently attired than the one in the series. The real Powell had been smart enough to shed his bloodstained coat rather than walk around the city with it. It had been found near the outskirts of Glenwood Cemetery on the afternoon of April 16 by an infantry private.

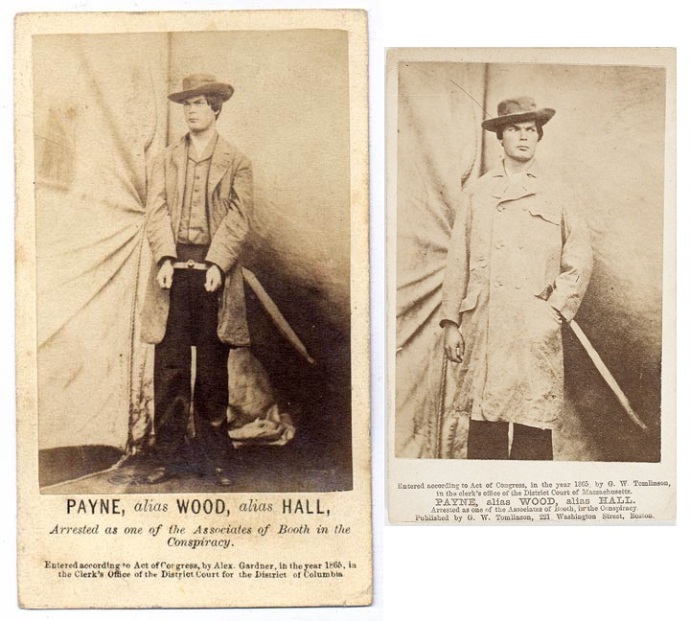

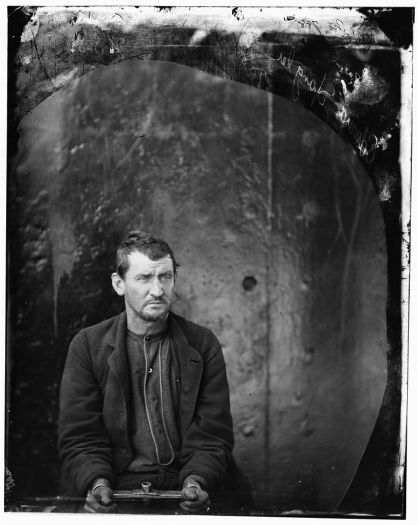

The two outfits of Lewis Powell. The left image shows how he was attired when he arrived at the Surratt boardinghouse on April 17 (minus the hat). The right image shows him wearing the outercoat he had worn while attacking Seward, which he later discarded.

Having also lost his hat, Powell was forced to construct a makeshift one. At some point during his three days of hiding out, he had cut off the end of his knit undershirt’s sleeve. He tied up one of the openings and then wore the sleeve remnant in the form of a stocking cap. While the series does show Powell creatively hatted, he was not wearing an entire shirt on his head.

The shift from a nighttime to a daytime arrival of Powell at the boardinghouse alters Mrs. Surratt’s story considerably, especially when it comes to her defense. As the detectives talked with Powell in the entryway of the house, the coach arrived to transport the household. Having learned from this stranger that he was apparently there to dig a gutter, Mrs. Surratt was asked, as she walked past him out the door, whether this was so. Looking at the man in the dim gaslight, she declared she had hired no man and had never seen the man before in her life. Later, of course, it was proven that Powell had lodged at the boardinghouse for two separate extended stays. Like Dr. Mudd’s denial of recognizing Booth when he came to his home, Mrs. Surratt’s failure to recognize Powell was fairly damning to her case. However, her defense had much more to work with. They established that Mrs. Surratt was very nearsighted, and they brought forth witnesses to say she had difficulty seeing at night. It was very late in the evening when the arrests occurred, and the gaslight had been turned down low. Dr. Blaine Houmes, a dear friend and fellow Lincoln researcher who has since passed, once gave a talk about the different medical aspects of the assassination story, and he chose to address Mary’s eyesight. He attempted to recreate what she might have seen based on descriptions of her eyesight and the described lighting in the hallway where Powell stood. This is what he came up with in trying to duplicate the scene.

I will note that Dr. Houmes was no Mary Surratt apologist and definitely felt she knew about what was being planned in her household. But we must remember that Mrs. Surratt was essentially just being walked past the man when the question of her hiring a laborer was posed to her, so she did not have long to study the man’s face. All of these factors make it possible that Mary truly didn’t recognize Powell at the moment. By placing this event during the daytime with Mary answering the door, seeing Powell clearly, and fleeing at the first chance she gets, the series has decided to remove all doubt as to whether she knew who he was or what he had done. As a person who definitely falls on the side that Mary Surratt was guilty and knew the assassination was going to take place, I still wish this scene had been a bit more ambiguous about Mary, especially this early on. But, again, I know this isn’t The Conspirator movie or even a show about Mary Surratt, so removing any doubt as to her guilt early on was probably the best way for this show to go about it so that it can really focus on Stanton and the manhunt.

3. Herold’s Trip to Bryantown

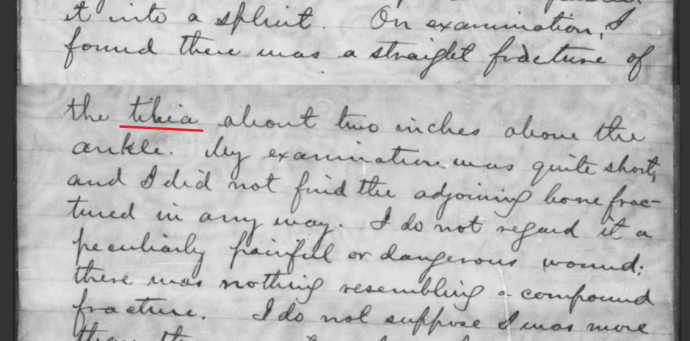

The first time in episode 2 that we see the fugitives, Booth is already hopping around the Mudd farm. This is in defiance of Dr. Mudd’s claim that he wouldn’t be up and about for two months with his fractured tibia. However, since Booth actually broke his fibula, it makes sense that he is up and about. Also, I have to print a retraction of one of my criticisms from episode 1. My friend Bob Bowser pointed out to me that while, yes, Booth definitely broke his left fibula, in his statement to the authorities on April 22, Dr. Mudd tells them Booth broke his left tibia.

Whether claiming the incorrect bone was broken is an error of memory on Dr. Mudd’s part or a deliberate lie to make Booth seem more wounded than he was, we can’t be sure. Having been told this, I’m a little bit better with the series having Mudd claim it was Booth’s tibia that was broken. At the very least, it can demonstrate that Dr. Mudd wasn’t the greatest doctor. But the wrong leg being broken is still a pretty big oopsy.

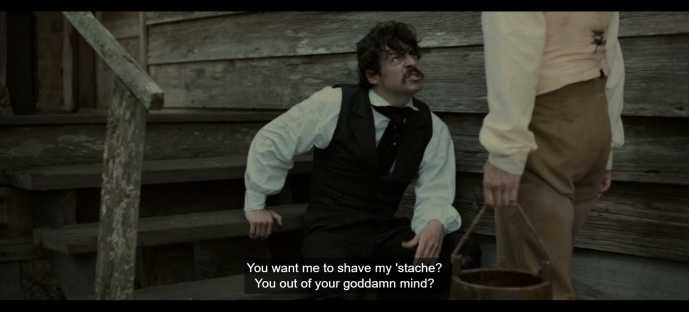

Anyway, Booth is up and about the Mudd farm and inquires to Davy how long it will take them to get to Richmond. Davy says a few days but that the horses need to graze first. Booth is insistent that their city horses will do better with oats or hay, but Davy says Mudd is low on supplies and that the doctor doesn’t want to go into town and attract attention. After some persuasion, Booth convinces Davy to ride into Bryantown to get horse feed and whiskey. When Herold suggests Booth shave his mustache, Booth angrily refuses claiming it is his “signature look.”

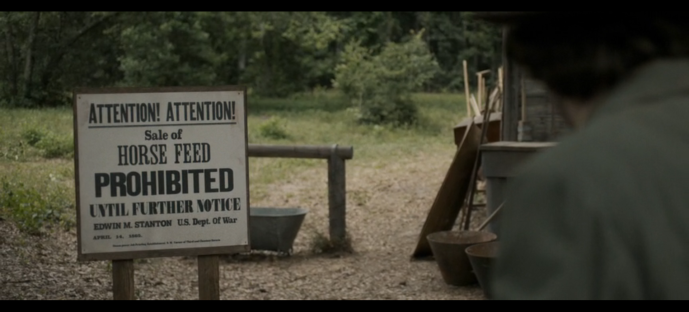

We then cut to Davy walking to Bryantown with a hand truck, intent on getting the vitally important food for the horses. But, due to Stanton’s orders in episode 1 to cut off all horse feed sales in the state of Maryland, Davy is stymied by a big sign next to the store. Unable to accomplish his task, he turns around and wheels his dolly back the way he came.

So, what’s the truth in this scene? Well David Herold did travel towards Bryantown on April 15. His purpose in traveling there was not to get horse feed but to see if he could secure a wagon that would make transporting the injured Booth easier. Though the series makes it seem like Dr. Mudd did not want to go to Bryantown, the doctor actually accompanied Herold for part of his journey there. On their way, they stopped at Dr. Mudd’s father’s farm and asked about a possible wagon or carriage, but they were told that none were available for use, especially since the next day was Easter and the family would need them to get to church on Easter morning. Herold and Mudd continued toward Bryantown but when they got within sight of the village, Herold observed that Union troops were in the city. They had just arrived that afternoon and were the first ones to inform the populace of the shooting of Lincoln the night before. Not wanting to risk capture (even though Herold’s name and involvement were probably not known to these soldiers yet), Davy turns around and rides back towards the Mudd farm to inform Booth. Dr. Mudd, meanwhile, causally visits the village intent on completing some shopping. He will always claim that it wasn’t until he was there in Bryantown that he learned that Lincoln had been assassinated. Unless Booth and Herold blabbed to him upon their arrival, this would have been his first opportunity to learn the news. The information gets the gears turning in Dr. Mudd’s mind, but he shows no great urgency to get back home. He finishes his shopping and even chats with neighbors about the news on his way back home.

I understand the series’ need to justify Stanton’s earlier order to cut horse feed, but I can’t help but feel that it would have been more dramatic for Herold to retreat from Bryantown at the sight of Union soldiers on the manhunt. It would more accurately show how close the authorities got to their prey at times, even if they didn’t know it.

4. The Signature Look

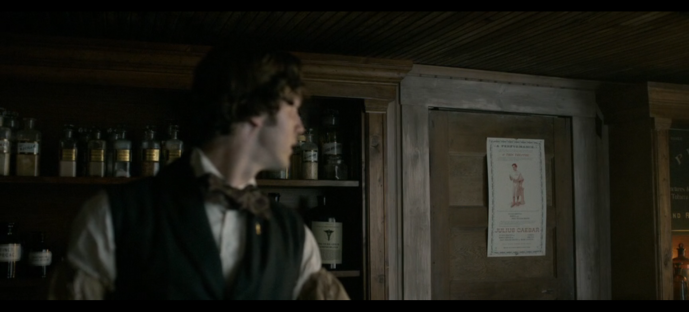

Immediately after Davy turns his hand truck around, the series shows a flashback of him from a year earlier. He is shown working as a pharmacist’s clerk, which was the young man’s real job. I was glad that the series gave some of Davy’s history, as this is often ignored. The scene shows John Surratt, Jr. for the first time as he talks of recruiting Davy into something big. This scene is completely fictitious and places the plot and John Surratt’s involvement in it way earlier than it should. Booth did not even come up with his plan to abduct the President until August of 1864. John Surratt did not meet Booth until just before Christmas of 1864 when he was introduced to the actor by Dr. Mudd (with Louis Weichmann present). While we don’t know the details of Davy’s recruitment, he had been familiar with the actor since the spring of 1863 when he went backstage after a performance at Ford’s Theatre and met Booth. So John Surratt’s offer to introduce Davy to Booth is completely backward. If anything, in April of 1864, Davy should have offered to introduce Surratt to Booth, seeing as he actually knew him at the time. What this completely fictitious scene does get right is Herold still being star-struck by the actor. This is demonstrated by Davy’s admiring tone regarding Booth and his having a playbill featuring JWB on the wall of the pharmacy.

We get a partial tracking closeup on the playbill and see that it is supposed to be from the famous New York performance of Julius Caesar the three Booth brothers did to raise money for a statue of William Shakespeare in Central Park. This performance actually happened in November of 1864, and no illustration of Booth or his brothers graced the face of the actual playbill. What this playbill shows is Booth’s so-called “signature look” as he plays a mustachioed Marc Antony.

While it’s true that in practically all of the photographs we have of John Wilkes Booth, he is wearing a mustache, that doesn’t mean he never shaved it off, especially when acting. In fact, the images taken after this specific performance of the Booth brothers are the ones that show him clean-shaven.

So, I found it a little unusual that Booth would be so adamant against shaving off his mustache in the series. As Davy aptly points out, his “signature look” is a sure-fire way to be recognized.

During the scene where Mary Simms comes to shave Booth’s face, his remaining uncertainty of whether to lose the ‘stache is also confusing since there really is nothing else for her shave. He is not shown wearing the fictitious fake whiskers that Dr. and Mrs. Mudd tried to claim he wore (which I appreciate), but he also doesn’t have enough stumble to even make shaving the rest of his face worth it. Luckily, after his confrontation with Simms, Booth has wisely made the correct choice to remove his mustache and is shown with a bare upper lip.

5. Mary Simms’s Backstory

Actress Lovie Simone has some great performances in this episode as Mary Simms comes face to face with the assassin, reflects on her backstory, and learns of Lincoln’s death by authorities who come to question Dr. Mudd. It’s important to remember that the Mary Simms in this series is a fictional character with only some basis on the real woman who was enslaved by Dr. Mudd and then left at the end of 1864 when slavery was abolished in Maryland. There were real Black servants on the Mudd farm during the time Booth was there who observed and interacted with the fugitives, but only a little bit of their experiences make up this composite Simms. The real Mary Simms bravely testified at the trial of the conspirators about the mistreatment she had received at the Mudd farm during slavery and of Dr. Mudd’s own disloyal statements and actions during the Civil War. The four other men and women who had been enslaved by Dr. Mudd and testified against him were her brothers Milo Simms and Elzee Eglent, along with Rachel Spencer and Melvina Washington. They are to be commended for speaking out. In total, out of the 347 people who testified at the trial of the Lincoln assassination conspirators, 29 of them were people of color. A few years ago, I wrote a final paper for one of my Master’s classes on the topic of these Black voices at the Lincoln assassination trial. If you are interested in reading more about these folks and the path to their testimonies, you can read the post here.

So, while I’m not going to spend too much time on Mary Simms since this version of her is a fictional character, I did want to address the backstory given to her in this episode. After retreating from Booth following the shaving scene, we are given a flashback of a young Mary in the free state of Pennsylvania playing cards with her uncle. Suddenly, a knock at the door informs Uncle Henry that “Mr. G.” is up here with marshals and that they have captured four men. This news sends the household scattering for weapons with which to defend themselves. Young Mary is frightened that Mr. G. and the marshals have come for her.

Uncle Henry confronts the posse of white kidnappers, telling them this isn’t Maryland. Mr. G. counters he has the right to reclaim his property. As the four already captured men are being placed in a wagon, white abolitionists from the neighborhood arrive. Uncle Henry tells Mr. G. to leave, but the leader is intent on being the bounty for little Mary. The scene ends with Uncle Henry grabbing for a gun in his waistband. Later in the episode there is another flashback of young Mary, seemingly after the unseen events from the first scene. It is now daytime and Mary returns to her cabin looking for her uncle. Unfortunately, the white kidnappers are inside waiting for her. They grab her and haul her away in a wagon as a Black man with a cane arrives and is unable to stop them.

Unfortunately, like so many people who were born into slavery, we don’t know the early life or backstory of the real Mary Simms. In truth, aside from the different testimonies at the conspiracy trial and an 1860 enumeration of the number and ages of people Dr. Mudd enslaved at that time, we have practically no documentation of her life. Mary Simms was 19 years old in 1860, according to the slave census. In all likelihood, she had originally been enslaved by Dr. Mudd’s father, Henry Lowe Mudd, Sr., and was then given to the son upon the doctor’s marriage and the completion of his home in 1859. In her testimony before the court, Mary Simms makes it clear that she had only lived with Dr. Mudd for around four years before she left. It would have been more appropriate for young Mary Simms to fear a return to slavery under “Mr. [Henry Lowe] Mudd” rather than Dr. Mudd.

It’s also possible that Mary had been enslaved by a relative of Mrs. Mudd’s. In the 1860 census, one of the people living at the Mudd house is Mrs. Mary Jane Simms. She was the widow of Joseph Simms but her maiden name was Dyer, as was Mrs. Mudd’s. The two ladies were first cousins. Given the habit of enslaved people, especially those born to a specific family, taking the last name of their enslavers, it’s possible that our Mary Simms had been born into slavery under the Simms family and then came to belong to Dr. Mudd after Joseph Simms died and his wife moved in with her cousin in 1859. This is just conjecture on my part.

I don’t find fault with the series making a more compelling backstory for Mary Simms. The actions of manhunters and kidnappers in the free states were a real threat to both freedmen and freedom seekers. This scene is clearly inspired by the real 1851 event of the Christiana Resistance.

The ending credits for this episode confirm the “Mr. G” in the scene is Mr. Gorsuch. In addition, the man who comes to warn Uncle Henry is credited as William Parker. The real Christiana Resistance was an important event in the antebellum period and one that actually worked to radicalize young John Wilkes Booth against the abolitionist cause. If you haven’t already read my deep dive into the Christiana Resistance, I implore you to check it out. It’s a story that far too few people know about, and yet it deserves to have an entire movie or miniseries made about it. While I would have preferred this series to have shown the Christiana Resistance in reference to Booth’s radicalization rather than as part of Mary Simms’ fictional backstory, I was still happy to see Manhunt give a nod to this important event.

Quick Thoughts

As you might imagine, it takes quite a long time for me to compose these historical reviews. I’m constantly consulting books in my library and a variety of digital sources to make sure what I write is backed up with sources. I pride myself on giving as much background on a subject as I can. But the truth is, I just don’t have the time right now to thoroughly cover every instance of dramatic license in Manhunt. I’ve spent more than 15 hours working on this review alone, and that is just not sustainable with my work and life commitments.

Actual photo of the ever increasing stacks of reference books pulled from my library in researching for this review.

So, I’m going to end this review (and likely the ones that come) by just summarizing some of the additional scenes or events that stuck out to me while watching this episode. While some of these aspects probably deserve to be fully fleshed out and explained more, I just don’t want to get burned out trying to thoroughly cover every single thing in the show. Next time, I will try and do a better job of focusing on the biggest points first, rather than just covering the episode in a chronological order as I did here. But I didn’t realize how long this single review was going to take me until several hours in. I apologize that the following points are lacking in detailed explanation, but it’s the best I can do this time.

- Dr. Mudd: This series shows a very different interpretation of Dr. Mudd than what has been portrayed in the past. In many ways, the Dr. Mudd shown in Manhunt is the antithesis of the “innocent country doctor” that the 1936 film The Prisoner of Shark Island portrayed. It is refreshing to see an antidote for Dr. Mudd’s “folk hero” status in the minds of many in the general public. I’m glad that this series is shining a light on Dr. Mudd’s role as an enslaver. However, the series is taking quite a bit of dramatic license in its portrayal of Mudd’s actions relating to Booth. Even though I think Dr. Mudd was a willing participant in the kidnapping plot, there is no evidence that he drew out a map for the fugitives, directed them to Rich Hill, and told them to eat the map if caught. And the ending scene of this episode in which John Surratt stays at the Mudd house on the night of April 16, is completely imaginary. John Surratt was nowhere close to D.C. or Maryland I’m sure we’ll see more of Mudd in episodes to come, and I might go into him a bit more then. But, for now, just remember that no depiction of Dr. Mudd as being completely innocent or completely guilty is an accurate one.

- Richmond: I don’t know why Booth is so keen to get to Richmond. The Confederate capital fell to the Union on April 3, and President Lincoln even toured the city afterward. If anything, Booth would have wanted to avoid Richmond because of the presence of so many Union troops.

- Surrattsville “Boardinghouse”: Many people get Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse in D.C. and tavern in Maryland confused. This series is no exception, as it also calls her tavern a boardinghouse in the caption that comes up during Stanton’s imaginary visit there.

- Secret Room: When John Surratt, Jr. was the postmaster at Surrattsville in 1863, he helped Confederate agents secretly transport letters across the line. This was done by placing an addressed letter bound for the Confederacy into an additional outer envelope addressed to a fictional person in Surrattsville. As postmaster, John would separate these letters out and then give them to Confederate couriers and smugglers who would cross with them over the Potomac River into Virginia. They would then remove the fictitious outer envelope, see the intended recipient in the South, and enter the letters into the Confederate mail system. If you were in the Confederacy and wanted to send a letter to someone in the Union, you addressed the letter with the correct information but did not put a stamp or return address on it. The letters would be smuggled across the Potomac to post offices like Surratt’s, where the rebel-leaning postmaster would stamp the letter and send it on its way using the U.S. mail system. It was an effective process, but Surratt was only postmaster for a few months before he was caught by Union authorities with Confederate mail and was removed as postmaster. The post office was then moved away from the Surratt tavern. Needless to say, there was no secret spy room at the Surratt Tavern, and the coded telegraph to John Surratt, Jr. from ‘The Office of Jefferson Davis” has no basis in reality. After losing his position as postmaster, John Surratt became a courier, transporting the mail and doing escort jobs for the disorganized Confederate “Secret Service.” Even when Surratt hyped up his clandestine activities after the war, he still comes across as a minor errand boy.

- “Cooking Utensils”: Mary Surratt claims she gave Booth “cooking utensils” as actors on the road as want to need. I’m not sure where this comes from. The closest thing I can think of is the pair of field glasses that Mary Surratt took down to her tavern on April 14 for Booth. Weichmann drove her down during this trip and saw the package but didn’t know what it was or who it was for. If I remember correctly, at one point, he said he thought it was perhaps a bunch of saucer plates stacked up. So this may be what the series is going for.

- Imprisonment: Stanton is shown visiting Mary Surratt and the other male conspirators in prison. Putting aside that no conspirators were arrested on April 15th, it’s unclear where this prison is meant to be. When Mary was arrested, she was initially held as a witness in the Carrol Annex of the Old Capitol Prison. As each of the men was arrested (minus Dr. Mudd), they were placed aboard the USS Saugus and USS Montauk at anchor in the Anacostia River. This was to prevent a possible mob from being able to access any land prison for fear if Booth was captured alive, an effort would be made to lynch him. Eventually, all of the main conspirators were transferred to the Old Arsenal Penitentiary, where their trial also occurred.

- No Real Threat to Stanton: Near the end of the episode, we see a shadowy John Surratt skulking outside of Stanton’s home on the night of April 15th. While it adds a degree of peril for our hero, nothing like this occurred. At the trial of the conspirators, an effort was made by the prosecution to place Michael O’Laughlen near the Secretary of War’s house on the evening of April 13th. This was during the Grand Illumination celebration. O’Laughlen was in D.C. and a few witnesses, including David Stanton, the Secretary’s nephew, claimed that a man fitting O’Laughlen’s description came to the house and asked about the Secretary. However, O’Laughlen’s defense team convincingly proved through a number of witnesses that O’Laughlen and his friends were partying a good distance away from Stanton’s home on April 13. It doesn’t look like this series is going to include Michael O’Laughlen or Samuel Arnold, both members of the abduction plot who bowed out before Booth shifted his plans to assassination.

- We’re on different timelines: Not to get all Marvel Cinematic Universe on you all, but it’s important to note that Stanton, Booth, and Mary Simms each end episode 2 on three different days, though exactly which days are not quite clear. The easiest known one is Mary Simms’s. This episode covers her experiences from Booth’s time at Mudd’s on April 15 to the morning of April 17, when she heads to the market and sees Booth’s wanted poster. The scene where Luther Baker comes to talk to Mudd about his guests is supposed to take place on April 15, the same day Booth leaves. We know this because, at the end of the scene, Mudd tells Mary and Milo to get to work because it “ain’t Easter yet.” Easter was on April 16 in 1865. We know that Booth’s arrival, departure, and the authorities’ arrival at the Mudd farm are all supposed to happen on the 15th because both Mary Simms and Dr. Mudd are wearing the same clothes in these scenes. Later, when John Surratt showed up, I originally thought this was still an April 15th event. But we can see that Mudd and Mary Simms have changed clothes in this scene. In addition, when Mudd tells Surratt he’d never guess what visitor he had, Surratt replies jokingly with “the Easter bunny” which makes sense if this was supposed to take place on the evening of April 16, Easter Sunday. Dr. Mudd orders Mary to go to the market the next day (April 17th) and this is the last time we see her. So, Mary Simms ends the episode on Monday, April 17th. Meanwhile, Stanton survives his longest day ever and visits with William Seward on the morning of April 16. Then he goes to the War Department, where Eddie Stanton suggests the Lincoln Funeral Train idea, which his dad approves and starts working on. The episode ends with Stanton, in the rain, bidding goodbye to Mrs. Lincoln and watching the funeral train depart. In reality, the Lincoln funeral train did not leave Washington until April 21st, and Mrs. Lincoln was not on board. We are unable to conclude what day we leave Stanton on in this episode. While it’s very hard to believe he was able to plan and execute the funeral train on the same day, April 16, you never know with Super Stanton. Booth and Herold never seem to leave April 15th. After leaving Dr. Mudd’s, they search for Rich Hill before meeting up with Oswell Swann, who reluctantly agrees to act as their guide. If this is still the 15th for Booth and Herold, then aside from the men traveling during the daylight hours, the series accurately shows the fugitive’s movements. They came upon Swann at around 9:00 pm and hired him to help them across the Zekiah Swamp. The ending scene of Swann, Booth and Davy riding fast through a random town is all for excitement purposes. In reality, Swann took the pair causally across the main roads to Rich Hill, and the fugitives were just lucky enough not to run into anyone else during their nighttime ride in the country. So Booth and Herold are on April 15, Mary Simms in on April 17, and Stanton is either on April 16 or some unknown rainy date in the future. EDIT: Right when I was looking to get a screen grab of the final scene with Booth racing through the unspecified village to close this review with, I noticed that in front of the church is a cross draped with a white sheet, signifying that Christ has arisen. This would imply that this riding scene is supposed to be happening on Easter Sunday, April 16.

Okay, so it turns out even my attempts at “quick” thoughts become overly verbose. I hope you’ll forgive me.

When I was sharing my initial disappointment over the mistakes in Manhunt with my wife, Jen, she asked me if I had ever seen the 2008 miniseries John Adams. I told her I loved that show when it aired and eagerly watched all the episodes. She then asked me how historically accurate John Adams was. I told her I had no idea. I assume they probably changed a bunch of stuff to make it more dramatic, but since I’m not a John Adams expert, I couldn’t tell you what those changes were. My brilliant lawyer wife then completed her well-developed argument by saying, “So there could have been a lot of historical mistakes in John Adams that you didn’t notice or even care about because you’re not an expert on John Adams. And yet, you still found the overall story and historical characters compelling. That’s how I am enjoying Manhunt.” Now Jen knows far more than the average person about Lincoln’s assassination. We met when I was a guest on her podcast covering the Booth escaped conspiracy theory. On her own she has noticed many things in the show that are different than what she’s read, but none of this has taken away from her enjoyment of the series. She has watched the series with me and has suffered through my constant squawking about how this-or-that is wrong to varying degrees. Yet she still loves the show and is looking forward to Friday’s episode, even knowing she will have to suffer through me again. That, if nothing else, should show you how good and compelling this series really is. Sure, it takes a lot of dramatic liberties and strays really far from the actual events. My little perfectionist historian brain has a tiny little conniption each time I see something that is wrong But I look over at Jen and see how much she is enjoying it, and I realize that I owe the writers of this series a debt of gratitude. This series is going to be great at bringing new and much-needed voices into our area of history. It’s too easy to become jaded and dismiss anything that doesn’t live up to our personal expectations. But the truth is, no media portrayal is ever going to be able to meet the expectations of an expert on a certain topic. While our visions of how things should be are well-informed and based on evidence, we are not the intended audience. Nor should we be.

Until next time,

Dave

those interested in the series manhunt should read the review of it by a Harvard history professor and regular contributor of the New Yorker magazine. The article appears in the March 18 th issue or can be read online or googled.

It was suggested elsewhere the other day that James Swanson might be upset about about changes that were made to his book. His comments in the following C-Span talk indicate his involvement with the project and his feelings about how it was handled.

https://www.c-span.org/video/?534032-1/james-swanson-manhunt-apple-tv-series

Thank you for this link. I was wondering how he felt about the serie and excellent interview showing his support and admiration for the actors and the sets.

Thank you, Dave, for preparing this thorough analysis for our information and education! The ending (how your wife enjoys it even though it’s inaccurate) adds balance.

Thanks for your reviews, Dave, they’re great. I’ve been watching it with my sister and we haven’t gotten much out of it besides making fun of some parts. I think we’re both too literal for things that stretch the truth so much – I know I am a very literal person. And with a history obsession, so, double whammy.

I’m nervous that a lot of people will come away from the show with totally wrong ideas of what went down. If the show decides to go full in on Ned Spangler being guilty, Johnson being complicit, or the Confederate govt. being directly behind the assassination, and so forth, those would strike me as pretty big misconceptions to have of the real events. I don’t think people come into this expecting that stuff to not be really true. Not that it matters so much, I guess, but it annoys me to present such errors of fact. And for what reason? It just seems irresponsible.

Not that Johnson doesn’t deserve the bad press, for instance, but if this show really does run with his complicity or having planned it, that’s crazy to me (from what I know). A Stanton show accusing Booth of having been encouraged by government higher-ups should be careful lol – of course it’s clear Stanton had nothing to do with it, but accusations since then should demonstrate you can accuse just about anyone.

We’ll have to see how they play it.

Dave, who were the guys who arrived first in the box after the shooting? The men pushing on the door when it was wedged shut. Was Forbes one of them? Are their names lost to history?

Manuel,

In the chaos of the event, we do not know the first people who entered the box after Major Rathbone dislodged the pine wedge barring the outer box door. It is believed that one of the earliest entries was Dr. Charles Leale, as he was the first physician to begin treating the wounded President. Also among the doctors who treated Lincoln in the box were Albert Freeman Africanus King and Charles Taft, the latter of whom was boosted up into the box from the stage below. Many people would later claim they were in the box after Lincoln was shot. Even more people claimed they assisted in carrying Lincoln out of the box and then across the street to the Petersen House. We’ll never know for certain who was really there.

Lost to history, very sad. But surely, Forbes HAD to be one of them……

Manuel,

As far as I know, there are no accounts of Forbes going into the box during the aftermath. Sadly we have no accounts by Forbes of his actions that night. Which would really be useful, especially since he was the last person to interact with Booth beforehand.

After Maj. Rathbone unblocked the door and the first group of people, including Dr. Leale, entered the box Rathbone ordered a nearby Lt. A. M. S. Crawford to guard the door and not let anyone in (unless they were a doctor, etc). If Forbes had stood aside and let other people try and get the box door open, then he would not have been allowed into the box once there was a guard.

No, Burnside was NOT at Ford’s the night of the assassination. I believe he was governor of Rhode Island.

Does anyone hold Edwin partly to blame? Methinks J.W. was trying to settle scores, real or imaginary, with his overachieving older sibling.

Edwin Booth was a ardent Unionist and Lincoln supporter.