On September 11, 1851, the small town of Christiana, Pennsylvania became the epicenter of an event that sent shock waves across the nation. Bloody conflict occurred, foretelling a national reckoning over the practice of slavery. Though this story contains a small connection to the Lincoln assassination story, the event widely known as the Christiana Riot is not a niche piece of history. It is part of our national identity. The following is an in-depth look at the event that resulted in the largest treason trial in American history.

The Rule of Law

In 1850 a series of five bills passed the United States Congress and were signed into law by then President Millard Fillmore. The bills, known collectively as the Compromise of 1850, were enacted in order to reduce the sectional conflict that was occurring in the states involving the issue of slavery and its expansion into new territories. The Compromise bills resulted in the acceptance of California as a free state; the formation of the territories of Utah and New Mexico under the rule of popular sovereignty which granted the citizens of the territories the power to decide if they would or would not have slavery; prohibition of the slave trade in Washington, D.C. (but did not abolish slavery in the nation’s capital); a revision of the borders of Texas in exchange for debt relief by the federal government; and finally, a strengthening of the 1793 Fugitive Slave Law.

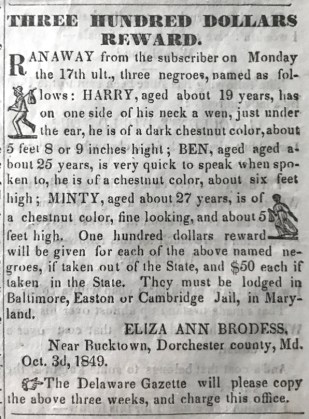

An example of a slaveholder’s advertisement for the return of runaways. The “Minty” named in this example is better known as famed Underground Railroad agent, Harriet Tubman.

Slavery was part of the United States since the country’s founding. In 1783, Massachusetts became the first state to immediately abolish slavery within its borders. Pennsylvania had started a gradual abolition of slavery starting in 1780. Other states in the north followed thereafter. As the number of free states increased, the federal government was faced with the issue of what was to be done regarding enslaved individuals who escaped their bondage and made their way to free states. In 1793, Congress passed the first Fugitive Slave Act which provided the first set of legal protections to slave owners seeking to retrieve runaways who had sought refuge in free states. This initial act was, as you might expect, extremely unfair to those accused of being runaway slaves. The burden of proof was on the accused to prove that he or she was not a runaway slave and this was nearly impossible as any black person seized was not allowed to testify on their own behalf or allowed a trial by jury. This resulted in countless free blacks being kidnapped from their homes in free states and being sent down south to become slaves. As time went on many free states began instituting jury trials for accused runaways and even granted them legal representation. Since it was up to the judge in the locale where the runaway was found to pass judgement, the effect of the initial Fugitive Slave Act weakened as abolitionist attitudes became more and more widespread in the north. This is what led to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law which strengthened the provisions of the act back in favor of slave owners much to the detriment to both runaway slaves and free blacks.

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law changed the responsibility for the recovery of runaway slaves to Federal, rather than local, authorities. Federal commissioners were appointed and it was their responsibility to issue warrants and rulings on the cases. Federal marshals were tasked with carrying out the warrants and making arrests, once again circumventing any local authorities. But the new Fugitive Slave Law was more than just a redistribution of responsibilities. The new law provided for the payment of the Federal commissioners based on their judgements. If a commissioner found in favor of the slave owner and authorized the return of a runaway (or kidnapping of an unrelated free black man or woman) he would receive a fee of $10. If he ruled in favor of the black defendant, allowing him or her to go free, the commissioner would only receive a fee of $5 from the government. As you might expect, the financial difference made most commissioners find in favor of slave owners even when their evidence of identity was flawed or contradicted. The Fugitive Slave Law also increased the fine charged against those who knowingly and willingly obstructed or hindered the recovery of a runaway. Those found aiding runaways and obstructing their retrieval could face a fine of up to $1,000 and six months in prison. The most hotly contested part of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law was how it made public assistance in the capture of runaway slaves mandatory. In the original 1793 Fugitive Slave Act, if one was asked by a person of authority for assistance in capturing a runaway, the person could decline. So long as they did not actively disrupt the efforts to capture the runaway there were no legal repercussions. The 1850 law, however, made it mandatory to assist Federal marshals recapture a runaway slave if asked. If any man over the age of 15 was commanded by a federal marshal to help him capture a runaway in the vicinity he had to comply or face arrest himself. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law essentially made every citizen of the United States a slave catcher and made all blacks, those born free and those who had escaped to freedom, subject to slavery on the command of any federal marshal or greedy commissioner.

It was for this reason that those free black and runaways who had the means escaped from the United States entirely in the 1850s. Many found refuge in Canada where communities of former slaves sprang up in Ontario. For those blacks who remained, especially those in rural areas or in close proximity to the borders of slave states, many formed self-protection societies. These groups would keep an eye out for gangs of slave catchers and federal marshals. They would pass word around about prospective “kidnappers” as they were called and come to the defense of those being forcibly abducted. One such protection society existed in the rural town of Christiana, Pennsylvania and it was informally headed by a runaway named William Parker.

The Call of Freedom

William Parker was born in about 1822, but like most enslaved people was never truly certain of his birthday or age. As he later recalled, “Slave holders are particular to keep the pedigree and age of favorite horses and dogs, but are quite indifferent about the age of their servants until they want to purchase. Then they are careful to select young persons, though not one in twenty can tell year, month, or day. Speaking of births, – it is the time of “corn-planting,” “corn husking,” “Christmas,” “New Year,” “Easter,” “the Fourth of July,” or some similar indefinite date. My own time of birth was no more exact; so that to this day I am uncertain how old I am.”

The location of William Parker’s birth was a sizable farm named Roedown Plantation. The farm still stands today in Anne Arundel County, Maryland near Davidsonville, Maryland. However, there are no extant buildings from Parker’s time there. The plantation belonged to a family by the name of Brogden, and by 1830, William Parker was considered the property of David McCulloch Brogden or, as he was known to the enslaved people on his farm, “Master Mack”. Growing up, Parker considered Master Mack to be a lenient owner who wouldn’t, “allow his hands to be beaten, or abused, as many slaveholders would, but every year [he] sold one or more of them, – sometimes as many as six at a time.” When Parker was ten years old he witnessed his first slave sale when he and all the other slaves were called to the big house for inspection. Parker and another young boy ran after seeing the proceedings and hid in a nearby wood until the sale was over. When they returned, they found they had luckily not been missed, but Parker’s Aunt Rachel and her two children had been among those who had been sold away. It was then that William Parker states he first started contemplating escape to states north or to Canada. However, it would take him a few years more to do so.

As the years went on, Master Mack continued to sell off his slaves a few at a time. Parker began to resent the methods in which the enslavers kept their human chattel in check and the hypocrisy of their condition. “There were many poor white lads of about own age, belonging to families scattered around, who were as poor in personal effects as we were; and yet, though our companions, when we chose to tolerate them, they did not have to be controlled by a master, to go and come at his command, to be sold for his debts, or whenever he wanted pocket money…I felt I was the equal of these poor whites, and naturally I concluded that we were greatly wronged, and that all this talk about obedience, duty, humility, and honesty was, in the phrase of my companions, ‘all gammon.’”

Things finally came to a head for William Parker on a day in June in about 1839 when he refused Master Mack’s order to go to the fields to work. While Parker had managed to reject the white propaganda that had tried to convince him of the importance of obedience, he still felt that running away required a reason more than just a belief in personal liberty. After getting into a bit of trouble with Master Mack after following the orders of a nearby neighbor, Parker decided that he would force a final reason to warrant his escape. After refusing to go out to work, Master Mack, “picked up a stick used for an ox-gad, and said, if I did not go to work, he would whip me as sure as there was a God in heaven. Then he struck at me.” That strike was the final straw that William Parker needed to break free from the mental chains that had oppressed him. William Parker fought back and at 17 was a strong and muscular young man. “We grappled, and handled each other roughly for a time when he called for assistance. He was badly hurt. I let go my hold, bade him good-bye, and ran for the woods. As I went by the field, I beckoned to my brother, who left work, and joined me at a rapid pace.” William Parker was now a runaway.

William Parker was one of the lucky ones. He managed to escape out of his neighborhood and make his way up to Baltimore. After hiding among the city’s black population for a week, Parker and his brother made their way up to York, Pennsylvania. Though now in a free state, this area of southern PA was filled with slave catchers and the pair was given advice to leave the area as soon as they could. The two men crossed over the Susquehanna River into Columbia, PA which was considered safe. It was here, in Lancaster County, that William Parker would make his home.

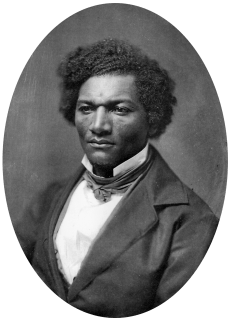

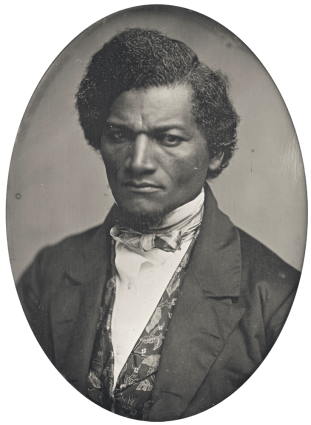

The Lion

Between his escape in 1839 and 1851, William Parker would be forced to live a fairly nomadic life in Lancaster County. While free from slavery, life was not easy for blacks in free states. The jobs open to blacks paid very little and consisted of only menial labor. The influx of Irish immigrants also created huge competition for even these low paying jobs. Parker was fortunate early on to find a job with a nearby doctor who was an abolitionist. Parker lived with the doctor for over a year and often listened as the doctor read abolitionist newspapers aloud to him. At one point, Parker had the opportunity to attend a speech by the noted anti-slavery speakers, William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass.

In a strange twist of fate, Parker had met Frederick Douglass when both men were slaves in Maryland years before. The speeches made a lasting impact on Parker, specifically the one from Frederick Douglass: “I listened with the intense satisfaction that only a refugee could feel, when hearing, embodied in earnest, well-chosen, and strong speech, his own crude ideas of freedom, and his own hearty censure of the man-stealer. I believed, I knew, every word he said was true. It was the whole truth, – nothing kept back, – no trifling with human rights, no trading in the blood of the slave extenuated, nothing against the slaveholder said in malice. I have never listened to words from the lips of mortal man which were more acceptable to me.”

Though William Parker could not read, write or speak as eloquently as men like Frederick Douglass, he shared in their vision of the end of the abomination that was slavery. From his new home in Pennsylvania, Parker began making efforts to help out in his own unique way. While Lancaster County was considered a safer haven than other parts of Pennsylvania, it was still relatively close to the border with Maryland and, as such, was subject to gangs of kidnappers.

“Kidnapping was so common, while I lived with the doctor, that we were kept in constant fear. We would hear of slaveholders or kidnappers every two or three weeks; sometimes a party of white men would break into a house and take a man away, no one knew where; and again, a whole family would be carried off. There was no power to protect them, nor prevent it. So completely roused were my feelings, that I vowed to let no slaveholder take back a fugitive, if I could get my eye on him.”

Parker, along with a group of five to seven other black men made the decision to band together to protect their community against kidnappers.

“[We] had formed an organization for mutual protection against slaveholders and kidnappers, and had resolved to prevent any of our brethren being taken back into slavery, at the risk of our own lives…Whether the kidnappers were clothed in legal authority or not, I did not care to inquire, as I never had faith nor respect for the Fugitive Slave Law.”

It was in this way that Parker became a de-facto black leader in Lancaster County. Though still a young man of about 17 when the mutual protection organization started, over the next twelve years he became a respected member of society in the region. While there were many whites in the region who were considered abolitionists, most were “non-resistant” or non-violent Quakers. The protection society was run solely by blacks for their own protection. Over the course of 12 years, William Parker put himself in danger many times freeing those who had been kidnapped by slave catchers. In one of the more daring stories, William Parker was shot in the ankle after helping to free a kidnapped man. For this and other acts of bravery in service to his fellow-man, one of the local Quaker underground railroad stationmaster described Parker as, “as bold as a lion, the kindest of men, and the warmest and most steadfast of friends.” Despite the danger to his own life that these recovery efforts caused, Parker was determined to protect his fellow-man.

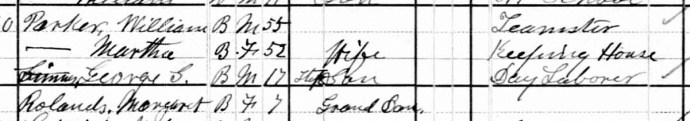

Even after Parker married and started a family, his daring efforts did not abate. In about 1845, William Parker married another escaped slave from Maryland named Eliza Ann Howard. Little is known about Eliza’s life prior to her escape to Lancaster County. William Parker only stated that her, “experience of slavery had been much more bitter than my own.” William and Eliza had three children during their time in Pennsylvania. At the time the new Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1850, William Parker and his family were living in a two-story stone home just outside of Christiana which they rented from a Quaker named Levi Pownall.

The Parkers were joined in their home by Eliza Parker’s sister Hannah, and her husband Alexander Pinckney. In 1851, the extended Parker family also invited a fellow runaway from Maryland, Abraham Johnson, to live with them. William Parker and the other men of the house made a living working as farmers and laborers on the nearby farms of rural Christiana while maintaining their protection organization in defiance of the Fugitive Slave Law.

The Runaways

A year before the newly strengthen Fugitive Slave Law was passed, four enslaved men named Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, George Hammond, and Joshua Hammond had made their way into Lancaster County. The men were runaways from a property called Retreat Farm in Baltimore County, Maryland. In November of 1849, they had stolen some grain from the barn of their enslaver, and had sold it in attempt to raise some money. Unfortunately, their middle man in the transaction, a free black with no land of his own to raise grain was questioned by the buyer as to where the grain had come from and he had admitted that he had acquired it from four slaves belonging to a Mr. Edward Gorsuch. When the four men learned that the scheme had been found out and that they would shortly be identified as the perpetrators in the theft, they made their escape. The theft of grain and subsequent escape of four of his slaves greatly disturbed fifty-four year old, Edward Gorsuch who considered himself a benevolent master. Compared to other plantations in the region, Retreat Farm was a small piece of land and Gorsuch worked side by side with his slaves in the fields. As Anthony Rice, PhD wrote in his thesis, A Legacy Transformed: The Christiana Riot in Historical Memory:

“Gorsuch labored alongside his human chattel developing a paternalistic relationship common to the antebellum era where he considered his slaves inferior members of his household rather than simple African savages…These were all self-serving emotions no doubt, a master’s method for rationalizing the necessity of enslaving others and assuaging the guilt that process entailed, but to Gorsuch these feelings were very real in constructing a self-image of the kindly master watching over his loyal slaves. Weaned on a southern culture that regarded the practice of enslaving others as symbolic of a gentleman’s wealth and status, Gorsuch considered the escape of his slaves a disgraceful insult. It was a personal betrayal, an impudent act that embarrassed him in the eyes of the community and stained his personal honor.”

To Gorsuch, it was inconceivable that his slaves would leave their homes and his benevolent care to become desperate runaways with no one looking out for them. Gorsuch’s paternalist view of slavery, which saw blacks as needing white man’s protection and guidance, made retrieving his “boys” paramount to not only to restore his self-identity, but, in his mind, for the sake of his slaves own well-being. According to Gorsuch descendants in 1911, Edward Gorsuch “had such confidence in his benevolence as their master that he always believed if he could meet or communicate with his runaways he could get them back.” The idea of freedom for its own sake was clearly a concept that the slave owner could not accept. While Edward Gorsuch received a few leads that made him believe his boys had made their way to Pennsylvania his requests to the Pennsylvania Governor for assistance in recovering his slaves fell on deaf ears. It wasn’t until nearly two years later (and the subsequent passage of the newly strengthened fugitive slave law) that Edward Gorsuch finally received some help in his search.

The assistance came via an unsolicited letter from a Lancaster County resident named William Padgett. Padgett wrote to Gorsuch stating he knew the location of the four men he was looking for and that if Gorsuch and a party would come up to Lancaster County, employ a federal marshal, and pay him for this knowledge, Padgett would lead the party to the runaways. As stated before, the passing of the Fugitive Slave Law created a lucrative business opportunity for slave catchers and informers in free states. According to a resident of Christiana at the time, William Padgett was a white farmhand and a mender of clocks. He would go around the county meeting runaway slaves. Through casual and seemingly friendly conversation, Padgett would learn where the runaways came from and the names of their former masters. He would then write to their masters, guide the slave catching parties and then get a reward. In this way, William Padgett betrayed many runaways to whom he portrayed himself as their “faithful friend”.

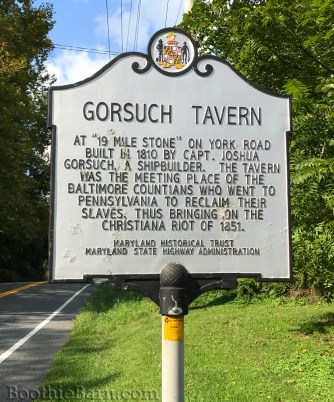

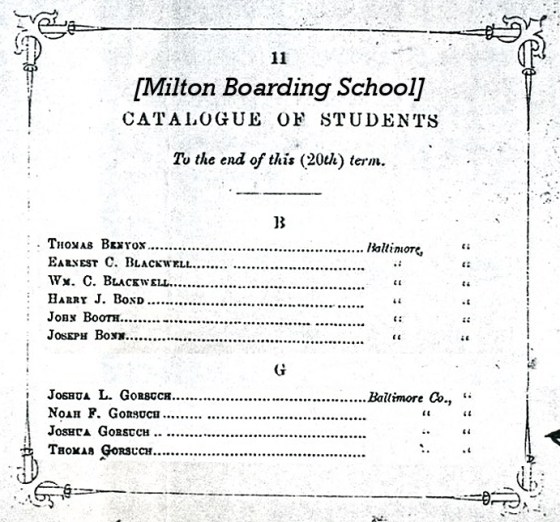

After receiving the letter from Padgett, Edward Gorsuch made preparations to take a party into Pennsylvania to capture the men. Local lore states that Gorsuch and his posse met to prepare for their trip in the old Gorsuch Tavern which still stands today in Baltimore County. The tavern had been built by one of Gorsuch’s ancestors and was situated on a farm adjacent to his own and belonging to his cousin. A highway marker in front of the old building mentions the tavern’s connection the subsequent events in Christiana.

The posse of slave catchers Edward Gorsuch assembled consisted of six: himself, his son Dickinson, his nephew Dr. Thomas Pearce, his cousin Joshua M. Gorsuch, and two neighbors, Nathan Nelson and Nicholas Hutchings.

A Watchful Eye

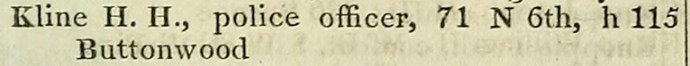

On September 8, 1851, Edward Gorsuch took an express train from Baltimore up to Philadelphia where he obtained four fugitive slave warrants the next day. Gorsuch was assigned a deputy marshal named Henry Kline to assist him in carrying out the warrants. Gorsuch also chose to employ two other officers to assist in the capture and paid them in advance. Unbeknownst to Gorsuch or Kline, the activities occurring in Philadelphia on September 8 and 9 were being observed by a secret vigilance committee of black abolitionists. The group, led by abolitionist William Still, had a series of men stationed around the fugitive slave offices whose aim was to intercept information about possible slave catchers and their activities. One of the agents learned that Gorsuch had been talking to Marshal Kline and then began shadowing Kline to learn of his destination. The agent’s name was Samuel Williams and when Gorsuch, Kline and the two other officers boarded a train departing Philadelphia late on September 9th, Williams followed them and even sat in the same train car as the posse. Samuel Williams had made no effort to hide himself and attempted to use his presence as a way of scaring the men off of their task. At one point in the journey, Kline got off the train early and Williams made the decision to continue following the marshal. Kline’s early departure from the train was to secure a wagon and a horse for the posse.

Dickinson Gorsuch was the second son of Edward Gorsuch and joined his father’s slave catching group in Christiana

The remaining men of Gorsuch’s group, including his son and neighbors were coming up from Baltimore on a different train. The plan was for them all to meet near Christiana in the early morning hours of September 10, meet up with Padgett the informer, and capture the men quickly and under the cover of darkness. In the meantime, all of the men, including Marshal Kline would make as though they were after a couple of horse thieves. Dickinson Gorsuch and the other men arrived outside of Christiana at around two o’clock in the morning of September 10. The large group now waited for Kline and the wagon to arrive. In a bit of bad luck for the slave catchers, however, the wagon Kline hired for the group broke down on his way to his destination and so he had to walk back to get another one. This delay caused Kline to miss his rendezvous with Gorsuch and the rest of the group just outside of Christiana. Not wanting to attract attention, the group retreated somewhat from Christiana. When Kline in his second wagon found there was no longer a group waiting for him at Christiana, he began roaming the backroads of Lancaster County looking for his group.

All the while Kline was being shadowed by Samuel Williams who had hired a horse of his own. In the early morning hours of September 10, Kline stopped in a tavern and asked if the bartender had seen any Marylanders stating that they were on the trail of horse thieves. The bartender replied in the negative and when Kline turned around he saw and recognized Samuel Williams behind him. Kline was likely unsurprised as he and the other two officers had also seen Williams on the departing train from Philadelphia. “Hello, Sam,” Kline remarked, “what are you doing here?” Samuel replied with, “Your horse thieves were here and gone. You might as well go home.” When Kline pretended not to understand Williams’ meaning the black abolitionist said to the marshal, “Oh, I know what you are about.”

Somewhere along the line of Samuel Williams stalking of Marshal Kline, Williams had become aware of Kline’s ultimate destination, Christiana. After their confrontation at the tavern, Williams left Kline behind and headed to Christiana where he began to spread the word that kidnappers were in the area. This news quickly made it to the ears of William Parker who said it “spread through the vicinity like a fire in the prairies.” All day on September 10, the region kept its eyes out for slave catchers.

Marshal Kline eventually found the Gorsuch posse at around 9:00 am on the 10th. It was now past dawn and too late for the men to make their attempt today. The presence of Samuel Williams had complicated things considerably. The two officers who had joined the group no longer felt they had the element of surprise on their side. They made arrangements to take a train back to Philadelphia. Gorsuch tried to persuade them to stay with the posse and even gave them more money to do so. The two officers took Gorsuch’s money and stated that they would return on the night train, bringing reinforcements with them if they could find some. The remaining group of seven men spent the day of September 10th in Gallagherville about 15 miles east of Christiana. At 11:00 pm the rested group boarded the outbound Philadelphia train to cover the final few miles to Gap which was situated just north of Christiana. The party was disappointed to find that not only were there no reinforcements on the train, but even the two officers had failed to return from Philadelphia as promised. At Gap the posse retrieved their rented wagon and met up with their disguised guide, who was almost undoubtedly their informer William Padgett. Gorsuch’s slave catching group set out under the cover of darkness in the early morning hours of September 11, 1851.

Marshal Kline eventually found the Gorsuch posse at around 9:00 am on the 10th. It was now past dawn and too late for the men to make their attempt today. The presence of Samuel Williams had complicated things considerably. The two officers who had joined the group no longer felt they had the element of surprise on their side. They made arrangements to take a train back to Philadelphia. Gorsuch tried to persuade them to stay with the posse and even gave them more money to do so. The two officers took Gorsuch’s money and stated that they would return on the night train, bringing reinforcements with them if they could find some. The remaining group of seven men spent the day of September 10th in Gallagherville about 15 miles east of Christiana. At 11:00 pm the rested group boarded the outbound Philadelphia train to cover the final few miles to Gap which was situated just north of Christiana. The party was disappointed to find that not only were there no reinforcements on the train, but even the two officers had failed to return from Philadelphia as promised. At Gap the posse retrieved their rented wagon and met up with their disguised guide, who was almost undoubtedly their informer William Padgett. Gorsuch’s slave catching group set out under the cover of darkness in the early morning hours of September 11, 1851.

“Kidnappers!”

The posse traversed the backroads of Christiana when they came upon a house where the guide informed them one of the fugitives was living. Gorsuch sought to split the group in half, with some staying here to capture the one runaway and the rest moving on to get the others. Marshal Kline disagreed and believed they required all of the men to retake the fugitives. In the end, Gorsuch decided to leave this house unmolested for now. The runaway living in this home had a wife who was still enslaved by Gorsuch. After retrieving the other men, Gorsuch believed he could convince this runaway to return with him without much difficultly. The party continued on to the next home, which according to the guide was where two of the runaways were staying. At one point during the trip, the group stopped along the side of the road for a break. According to the Marshal Kline, “One of the party had a carpet bag, and we took out some cheese and crackers which we [ate], and we fixed our ammunitions and started.” The group’s progress was slower than expected and a soft light was beginning to glow as dawn approached rapidly. “It was a heavy, foggy morning” which aided in concealing the group even as the light began to grow. Finally, the posse arrived at a short lane leading to a home where two of the runaways were staying. The guide pointed to the home, a two-story house made of stone, and then left so that he would not be seen with the slave catchers.

As the remaining seven men, six Marylanders and Marshal Kline prepared to march up and enter the house, a black man came whistling down the lane. This man was Nelson Ford, one of Gorsuch’s runaways who was leaving the home early for work. In a moment, Ford locked eyes with the master he had fled from two years ago. The shared recognition was instantaneous. In a blur, Ford spun around and ran back up the lane. He threw open the house’s door and woke up the rest of the household with the yell of, “Kidnappers! Kidnappers!” Gorsuch’s posse quickly moved to surround the house and prevent any escape and when that was done, Edward Gorsuch and Henry Kline barged through the open door after Ford. They found that the whole household had fled up the stairs and there were sounds of firearms and makeshift weapons being gathered above their heads. Despite this, Gorsuch believed that his success was at hand and that very shortly two of his runaways would be returned to him. He had the rule of law with him and was likewise confident in his own ability to bring his boys back into the fold. Unbeknownst to Gorsuch however, was that he and his posse had just entered the lion’s den for the man who owned this house; the man who was sheltering two of Gorsuch’s runaways was the lion himself, William Parker.

How long Nelson Ford and Joshua Hammond had been staying with Parker and his extended family is not known for certainty. One account said they had fled to Parker’s only the day before out of concern regarding the rumors of slave catchers. Other accounts make it appear that one of both of them had been living with the family for some time. Regardless when the Parker household ran upstairs they numbered the same as the slave catching group. There was William Parker, his wife Eliza, Hannah Pinckney and her husband Alexander, Abraham Johnson, Nelson Ford and Joshua Hammond.

When Gorsuch and Marshal Kline entered the home, the slave owner yelled for his boys to come down and give themselves up. He promised that if they surrendered themselves quickly and came away peacefully he would forgive them and treat them as kindly as before. He was there under the authority of the law and they had no choice. William Parker, appeared at the head of the stairs. “Who are you?” Parker demanded of the two men. Kline stepped forward and stated, “I am the United States Marshal.”

“I told him I did not care for him nor the United States, “ Parker recalled, “I then told him to take another step, and I would break his neck.” With that, Kline retreated a step, attempting to cool the situation down a bit. He spent time reading aloud the legal warrants he carried with him for the capture of Ford and Hammond.

There were mixed emotions upstairs in the Parker home. Alexander Pinckney, himself a runaway slave, briefly felt the situation hopeless. “Where is the use in fighting? They will take us.” Marshal Kline overheard this statement and yelled up to the group, “Yes, give up, for we can and will take you anyhow.” Parker, the lion who fought for his people, urged Pinckney and the rest not to relent and reminded them of the greater cause they were fighting for. He urged them, “not to be afraid, nor give up to any slaveholder.” Parker announced downstairs that they were all willing to fight to the death in order to maintain their freedom.

Edward Gorsuch had grown tired of the continued parley. He believed Parker’s threat to be merely bluster and was determined he could reason with his boys if he could get them away from this blowhard. “Come, Mr. Kline, let’s go upstairs and take them. We can take them. Come, follow me. I’ll go up and get my property. What’s in the way? The law is in my favor, and the people are in my favor.”

Parker called down to Gorsuch stating, “See here old man, you can come up, but you can’t go down again. Once up here, you are mine.” With that a metal fishing spear was suddenly hurled down the stairs at the men. The projectile missed them but scared them enough to cause the two men to retreat outside the home for a bit.

Nothing was going according to Edward Gorsuch’s plan. How could this black man stand in the way of law and order? Who was he to defy not only Gorsuch but the laws of the United States? Angry, Gorsuch yelled up at the house demanding the return of his property. Parker answered him with, “Go in the room down there and see if there is any property there belonging to you. There are beds and a bureau, chairs and other things. Then go out to the barn; there you will find a cow and some hogs. See if any of them are yours.” Gorsuch replied, “They are not mine; I want my men. They are here, and I am bound to have them.”

Raising the Alarm

As William Parker verbally spared with Gorsuch and Kline, an unexpected sound arose from another of the house’s windows. Eliza Parker, sharing in her husband’s defiance, blew into a tin horn which emitted a loud trumpeting over the early morning countryside. The sound of a horn at an unusual hour was a local custom of alarm and brought neighbors promptly to the site of the alarm to see what the problem was.

“What do you mean by blowing that horn,” Marshal Kline angrily demanded and with that he ordered the other men in the posse to shoot at the trumpeter. Eliza Parker was suddenly engulfed in a barrage of bullets. She dropped down to the floor but did not give up her blowing. With the horn on the window sill and bullets ricocheting off of the stone walls, Eliza continued to blow the trumpet over and over again. It was these shots, fired by the gang of Marylanders at his wife, that Parker claimed were the first bullets that flew that morning. Parker and the other men upstairs in the house proceeded to fire down at the posse. The gunfire ended in a stalemate, with neither side inflicting a hit. Once again Gorsuch and Kline attempted to negotiate the household’s surrender with Kline highlighting the dangers in store for them if they should continue to resist.

Gorsuch called out to Parker, “Give up and let me have my property. Hear what the Marshal says; the Marshal is your friend. He advises you give up without more fuss, for my property I will have.” Parker once again denied having any property belonging to Gorsuch. “You have my men,” Gorsuch replied, once again forced to admit that he was seeking human beings. Standing in view of the window Parker asked Gorsuch, “Am I your man?” to which Gorsuch replied no. Parker then brought his brother-in-law Alexander Pinckney to the window and inquired, “Is that your man?” Gorsuch once again replied in the negative. Lastly, Parker brought Abraham Johnson to the window and repeated the question. Gorsuch again answered no. Rather than bringing Hammond and Ford forward, as they would undoubtedly be recognized, Parker was forced to bring Pinckney and Johnson in front of the window again having them pretend to be two more men not yet seen. Parker then told Gorsuch that those were the only men in the house, which Gorsuch knew to be a lie since he had seen Nelson Ford run into the home. At that point one of the other men in Gorsuch’s party, perhaps his cousin Joshua Gorsuch, attempted to use theology to end the situation to his group’s satisfaction. The man stated that while abolitionists claim men could not be property, the Bible was the conclusive authority and said otherwise. Edward Gorsuch, a religious leader back home who had instilled the importance of scripture into his own slaves took up this gambit.

“Does the Bible not say, ‘Servants, obey your masters?’” Gorsuch called out. Parker agreed that it did but counter that the book also stated to “Give unto your servants that which is just and equal.” At this point a mutual scripture inquiry began between Gorsuch and William Parker. Parker had been well-educated in the Bible during his time as a slave and knew all the arguments of obedience that Gorsuch would employ. During his time in Lancaster County, Parker had increased his knowledge of the Bible and was known as “preacher” to many in the area. The two men parried with each other, Gorsuch quoting Scripture in defense of slavery, and Parker quoting scripture in defense of liberty.

“Where,” Parker asked Gorsuch, “do you see it in Scripture that man should traffic in his brother’s blood?” To this accusation Gorsuch replied, “Do you call a nigger my brother?” When Parker replied yes, Edward Gorsuch became enraged. He screamed out, “My property I will have, or I’ll breakfast in hell!” and he stormed back into the house. Gorsuch was halfway up the stairs when he looked up and saw the Parker household all trailing their weapons on him. Gorsuch’s 25 year old son, Dickinson, rushed inside to stop his father. Dickinson, and the guns pointed in his direction, cooled Edward Gorsuch for the time being, but he was still determined to retrieve his property.

Upstairs in the house, Alexander Pinckney was losing his nerve once again. The resolve in Gorsuch’s eyes a few moments before had shaken Pinckney up. “We had better give up,” Pinckney said to Parker. “I am not afraid…but where is the sense in fighting against so many men, and only five of us?” Pinckney apparently did not count the two women, Eliza and his own wife Hannah, amid the group of fighters. Parker tried once again to calm his brother-in-law but Pinckney was more adamant this time. “No, I will go down stairs”. To that Parker stated that if Pinckney made an attempt to go down the stairs he would blow his brains out himself. “Don’t believe that any living man can take you,” he said. “Don’t give up to any slaveholder.” Rallying support, Parker turned to his friend Abraham Johnson asked him what he wanted to do. Johnson replied “I will fight till I die.” At that moment, Eliza Parker also joined the call. The woman who Pinckney had completely disregarded a moment earlier seized up her weapon, a large corn knife, and “declared she would cut off the head of the first one who should attempt to give up.” With this display Alexander Pinckney, whether through fear, shame, or renewed passion, went back to his place at one of the second floor windows. From his vantage point, he witnessed a sight that removed any lingering doubts in his mind: the cavalry was coming.

Surrounded

Eliza Parker’s blowing of the tin horn had echoed through the countryside. The local blacks, already on high alert from Samuel Williams’ warning of kidnappers in the region, answered the call quicker than usual. While the horn could also signal fire in the area, pretty much all of the black citizens came to the Parker house with some form of weapon. Like Eliza Parker, many carried long corn knives. Others had clubs and axes. Only a few had guns. The number of men who reported to the Parker home varies considerably from different sources. Witnesses at the subsequent trial would identify a group between 50 and 150, but most historians feel that this number is exaggerated given the number of people living in the vicinity of the Parker place. The true number of blacks who came upon the Parker home in response to Eliza Parker’s alarm may be as low as 15 to 25, but to the seven people huddled upstairs surrounded by slave catchers, those 15 to 25 men were an army.

It was now the posse of Marylanders’ turn to feel uneasy. Nothing had worked out the way they had planned. What was supposed to have been a quick extraction under the cover of darkness had turned into a prolonged and now crowded affair by the dawn’s early light. For quite some time the three distinct groups, Parker’s group inside, Gorsuch’s posse outside, and the gathering blacks surrounding them did nothing. Gorsuch refused to leave without his property despite the seemingly increasing danger.

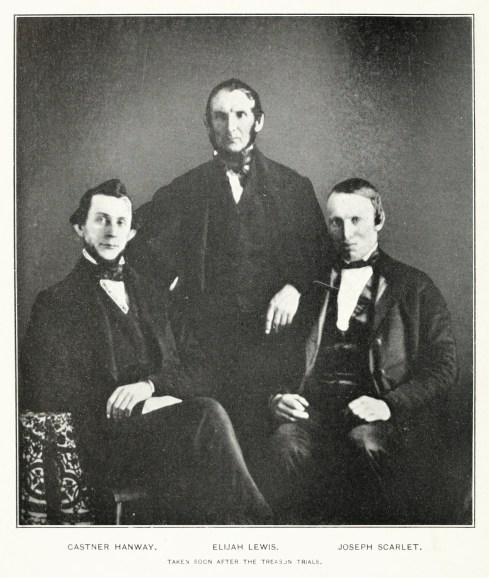

Into this situation rode up two local white citizens, a Quaker storekeeper named Elijah Lewis and a miller named Castner Hanway. They had been alerted by local blacks that kidnappers were around William Parker’s place and that it was hoped they might help defuse the situation. As they arrived, they were greeted by Marshal Kline who was no doubt happy to see additional white faces. Lewis and Hanway informed Kline that they had been told that a kidnapping was underway here and they had come to see for themselves if it were true. Kline presented Lewis and Hanway a copy of his warrants for the two men inside the Parker home. Though abolitionists themselves, both Lewis and Hanway could see that the recovery of the Gorsuch runaways was perfectly legal and not a case of kidnapping in the literal sense. Kline then sought to employ Lewis and Hanway to assist in the capture of the men. Lewis and Hanway refused. Kline explained that the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Law required them to assist him. Again, however, the two white men refused. They would not interfere with the legal capture of runaway slaves, but they would not be a party to it either, no matter what the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Law said. Wanting to avoid any violence, the two men stated to Kline that they would assist him by attempting to persuade the assembled men to leave the area.

As this was going on, an additional reinforcement arrived on Parker’s side. This man was Noah Buley, another of Gorsuch’s runaways who, rather than taking this moment to flee, came to the defense of Parker and his fellow runaways. Buley rode up on a horse, fastened it to the lane, loaded his gun, and watched. Lewis and Hanway’s attempt to disperse the gathered group of men was, unsurprisingly, unsuccessful. Hanway told the Marshal that, “the colored people had a right to defend themselves and [he] had better clear out, otherwise there would be blood spilt.” With that Elijah Lewis and Castner Hanway began riding out down the lane heading away from the home. Marshal Kline followed them on foot begging for them to try harder to disperse the group surrounding his posse.

The arrival of reinforcements and the retreat of Lewis and Hanway bolstered the group inside the house. As a sign of their strength and determination not to be taken, Parker and the men of the house, including Gorsuch’s runaways, exited the house and stood together. Edward Gorsuch was seething over what was occurring and over his slaves’ overt display of defiance. They were no longer hiding but were standing like equals in his presence and refusing to obey him. Some of the others in the posse, including Gorsuch’s son Dickinson attempted to convince his father to allow them to depart. But Gorsuch would not yield. Seeing his runaways in broad daylight openly defy him was the last straw. “My property is here, and I will have it or perish in the attempt.”

Bloodshed

The exact details of what occurred next are difficult to know for certainty due to the conflicting accounts of those who were present. The most reliable accounting of events places an incensed Edward Gorsuch walking right up to the line of men outside of Parker’s home. Edward Gorsuch approached Joshua Hammond, one of the runaways he sought to retrieve. Hammond stated, “Old man, you had better go home to Maryland.” “You had better give up, and come with me,” shouted Gorsuch. At that, Hammond clubbed his former master with a revolver, knocking him down. When Gorsuch tried to get up, Hammond pistol-whipped him again. With Edward Gorsuch at the ground at his feet, Joshua Hammond took his revolver and fired once at his former master. Dickinson Gorsuch ran towards the men hoping to come to his father’s aid, when he was clubbed in the right arm causing him to drop his gun. Now disarmed, Dickinson turned to run when Alexander Pinckney unloaded two shotgun blasts on him. Dickinson was hit in the right side and crawled to a fence corner where he collapsed.

The remainder of the posse, who as you’ll recall were without horses of their own, could do nothing but run. Marshal Kline, Nathan Nelson, and Nicholas Hutchings were already a distance down the lane when the violence erupted at the house. They were able to make their escape following the departing Elijah Lewis. As attention was drawn on the beating of Edward Gorsuch, Dr. Pearce, his nephew, elbowed his way through the crowd, jumped the fence and ran down the lane toward Joshua Gorsuch who was standing near Castner Hanway’s horse. Dr. Pearce’s flight was followed by bullets which whizzed by him with one passing through his hat and grazing his skull. Out of the posse of men, it was only Joshua Gorsuch who got a shot off though it was fired wildly and at no one in particular. In making their escape, Dr. Pearce and Joshua Gorsuch found themselves running beside Castner Hanway. Dr. Pearce would later tell people that Hanway used his horse to shield himself and Joshua Gorsuch from the mob. This protection did not last long however as Hanway did not want to endanger his own life for these slave catchers. He put the spurs to his horse and galloped down the lane. Finding themselves being overtaken, Pearce and Joshua Gorsuch split up. Pearce successfully made it into a field but Joshua was overtaken. A group of men beat him severely over the head with a gun but did not kill him. Joshua wandered away from the beating in a daze but was fortunate enough to run into Marshal Kline who took charge of the man and found him medical attention.

Back at the Parker home, Edward Gorsuch, the 56 year-old Maryland slave holder, lay dead. Despite later newspaper accounts that stated that Gorsuch was beaten beyond recognition, the coroner’s inquest stated he only had a fracture of the left humerus (upper arm) and died from a single gunshot wound. Dickinson Gorsuch was bleeding from the over 70 shot he had received in the side from Alexander Pinckney’s shotgun when he was found by a local Quaker by the name of Joseph Scarlett. Acting as a sort of Paul Revere, Scarlett had been riding through the neighborhood raising the alarm of kidnappers at Parker’s and had only arrived on the scene after the shooting had stopped. Scarlett gathered up the critically wounded Dickinson and took him to the nearby farm of Levi Pownall. Dickinson would spend the next few days at the Pownall farm being tended to. He would later write in deep appreciation to the Pownalls for their assistance in his time of need.

Escape

The victory over the Fugitive Slave Law came at a high price. In the immediate hours after the resistance at Christiana, Gorsuch’s runaways fled the region, the assembled reinforcements returned to their homes, and William Parker, Alexander Pinckney and Abraham Johnson hid on the nearby farm of Levi Pownall, the same man who was at that time caring for the wounded Dickinson Gorsuch. At nightfall Parker and the other two inquired with Levi Pownall about Dickinson’s condition. Pownall told them that the young man was near death and that authorities would assuredly be arriving en masse soon. According to author Anthony Rice:

“It was at this moment when the black men grasped the gravity of the situation they now faced. Their actions went beyond anything the mutual protection association had done in the past. This was not a case of beating up a few slave catchers and disappearing mysteriously into the night. Parker and his compatriots had blood on their hands; they were fugitive slaves who killed a respected slaveholder and gravely wounded his son before dozens of witnesses. Black had conquered white in a country that knew only the opposite and would demand its just recompense. Although they could claim self-defense, their resistance was so charged with political implications that receiving an impartial trial seemed remote. The black men soon came to the realization that one of two things awaited them in Pennsylvania – a prison cell or the gallows. They reluctantly decided to leave their friends and families behind in order to flee north and hopefully cross into Canada.”

The journey was undertaken with Parker, Pinckney and Johnson travelling together without their wives or children. The assumption that the women present in the home during the fight would not face trial proved to be a correct one for while Eliza Parker and Hannah Pinckney would find themselves arrested in the immediate aftermath, they would eventually be released without charge. The three men slowly made their way north. On September 20, nine days after the bloody dawn of the resistance, Parker and his group found themselves 500 miles from Christiana in Rochester, New York. They were on the final leg of their journey as a crossing of Lake Ontario to the north would find them in Canada. In Rochester, Parker, Pinckney and Johnson found shelter and assistance from a familiar Underground Railroad agent, noted abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

As stated previously, Parker had been acquainted with Douglass years before when they were both enslaved in Maryland. After escaping to Pennsylvania, Parker was incredibly moved after hearing Douglass speak in the area. Now, for the third time, their paths would cross and this time it was Douglass who was moved by Parker. As Douglass would later write in one of his autobiographies, “I could not look upon them as murderers. To me, they were heroic defenders of the just right of man against manstealers and murderers…What they had done at Christiana, and the cool determination which showed very plainly especially in Parker, left no doubt on my mind that their courage was genuine and that their deeds would equal their words.” Both Parker and Douglass knew the danger that the famous abolitionist was putting himself in for harboring the fugitives and so they only stayed over the course of a day while Douglass made arrangements for them to book passage on a ship bound for Canada. Despite the danger, however, word spread through Rochester’s abolitionist circle that William Parker, the hero of the Christiana Riot was stopping at Douglass’ home. In a short time, Douglass found his home inundated with visitors who wished to meet Parker. “The hours they spent at my house were therefore hours of anxiety as well as activity,” Douglass recalled. At 8 o’clock in the evening, Douglass rode with Parker, Pinckney and Johnson to the Genessee River where a steamer was scheduled to depart in 15 minutes. Douglass stayed on the steamer with the men until the last possible minute before providing them with ten dollars and shaking their hands. In gratitude for his help and for the work he would continue to do on behalf of the enslaved, Parker gave Douglass a parting gift, the revolver carried by Edward Gorsuch that Parker had picked up after the slave-owner’s death. With that, Douglass stepped off of the ship and watched as it departed down the river. In the next edition of Frederick Douglass’ weekly abolitionist newspaper, a front page story titled, “Freedom’s Battle at Christiana” contained specific details of the event that Douglass could only have gotten from Parker himself, but the article made no mention of the fugitives’ recent stopover in Rochester. Both Parker and Douglass would stay quiet about this part of the escape for years and even when Parker wrote about the event in 1866, he would still protect the identity of the “friend of mine” who aided them in Rochester.

Frederick Douglass and the other abolitionist newspapers would continue writing about the events in Christiana, working as a counterpoint to the propaganda being generated by Southern newspapers. When news of the event flashed across the nation it was subsequently dubbed the Christiana Riot by the pro-slavery South. The number of “rioters” numbered in the hundreds instilling fears of massive slave uprisings. Sensational stories regarding the condition of Edward Gorsuch’s body and the savage treatment it received abounded. Gorsuch, it was said by some newspapers, was scalped, riddled with bullets, and was even said to have had his genitalia cut off. The demand for justice over Gorsuch’s death was widespread and it was only in the abolitionist newspapers that the event was given its proper context.

Retribution

Christiana was beset by gangs of men of differing levels of authority in the aftermath of the resistance. Local police, federal marshals, and even forty-five marines were dispatched to the small Pennsylvania town to arrest those responsible. Added to these deputized groups were also the roving gangs of Marylanders and slave catchers who took advantage of the confusion. The posses ran rampant over the area, kicking in doors, tearing up houses under the guise of looking for the fugitives, and attacking residents both black and white. Warrants were made out for the three white men who had been present during and after the battle. Elijah Lewis, Castner Hanway, and Joseph Scarlett were carted off to Moyamensing Prison in Philadelphia where they would remain until tried. This condition was also suffered upon by countless blacks in the area who were rounded up in the ensuing days.

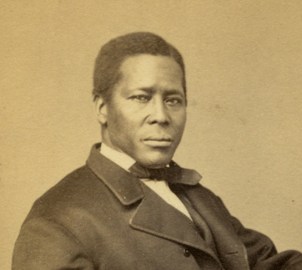

Ezekiel Thompson, one of the men actually present at the Christiana Resistance who suffered arrest and imprisonment.

Francis Lennox, a white Christiana schoolmaster, recalled the days’ scenes, “There were a number of United States Marines; I asked one what they were doing here; he said, ‘We are going to arrest every nigger and damned abolitionist…’ I walked away. Sure enough they scoured the country for miles around arresting every colored man, boy and girl that they could find.” The resistance at Christiana was the pretext for a widespread incarceration of the black population in Lancaster County. Even those blacks who had white neighbors vouching to the fact that they were nowhere near the Parker home were taken away. Countless slave catching groups used the opportunity to kidnap suspected runaways and take them south for a profit. After a few days the arrests stopped as local abolitionists decried the mass and unwarranted arrest of the citizenry. Marshal Kline was then required to identify those among the imprisoned who were actually present at the riot. He was aided in this nearly impossible task by a local black man named George Washington Harvey Scott, who Kline had identified among those present at the riot and had arrested. Scott provided corroborating testimony and helped Kline identify among the other arrested blacks who had been present. In the end, 38 individuals were indicted in the murder of Edward Gorsuch, including the absent William Parker and his men.

A monument erected in 1911 in Christiana lists the 38 men indicted in Edward Gorsuch’s death. Click to enlarge

The trial of the Christiana resistors had deep implications to those in the South. The case was far more than the murder of a single slaveholder, but spoke of open and bloody defiance against the Fugitive Slave Law. Residents of the South had severe doubts over the ability of a Pennsylvania jury, tainted with their abolitionist views, to mete out justice and prevent disunion. Governor Louis Lowe of Maryland wrote an open letter to President Millard Fillmore pressuring the federal government to take action in this case on behalf of law and order, “I do not know of a single incident that has occurred since the passage of the Compromise measures, which tends more to weaken the bonds of union, and arouse dark thoughts in the minds of men, than this late tragedy. Nor will its influence and effects be limited within the narrow borders of our States. They will penetrate the soul of the South. They will silence the confident promise of the Union men and give force to the appeals of the Secessionists.” Gov. Lowe made himself clear, “There is but a single corrective,…the most complete vindication of the laws and the fullest retribution upon the criminals.”

In the end, the Fillmore administration realized the precarious nature of their position and the need to appease the South to prevent Civil War. Thus the United States government elevated a murder trial of a Maryland slaveholder into the largest treason trial in American history. The bloody defiance of a few blacks in Christiana was deemed not just the breaking of the Fugitive Slave Law but fomenting of insurrection against the entire United States government.

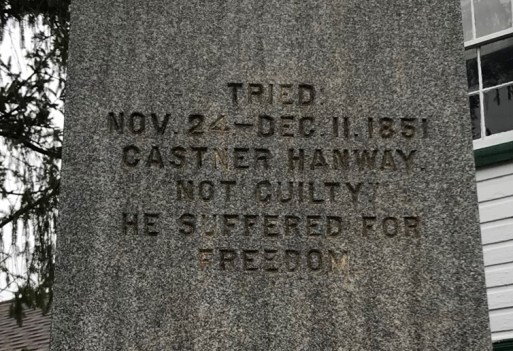

The Trial of Castner Hanway

The task of proving treason was the job of John W. Ashmead, U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. Ashmead decided the best course of action was to try the defendants individually rather than as a group. Ashmead would start with his strongest case first portraying the subsequent defendants as following this ringleader. In the end, the government sought to portray the white miller, Castner Hanway as the defacto leader of the treasonous group of blacks. While the bloody actions of the resistors were without question, the prejudiced thinking at the time held that the idea of rebellion could not have started in the underdeveloped minds of these negroes. Surely it was the abolitionists and the white residents of Christiana like Castner Hanway who poisoned the minds of these otherwise obedient blacks. Even the court that sought punishment for the ultimate crime against the government could not acknowledge the independent and equal thought of the perpetrators because of their race.

While it was the government’s strongest case, there was an understanding in the Fillmore administration that a verdict of treason was highly unlikely given the evidence. Hanway was a fairly recent arrival in Christiana and, though anti-slavery in feeling, he was not known to be an ardent abolitionist. Among the biggest pieces of evidence against him was the testimony of Marshal Kline. Kline claimed that upon Hanway’s arrival on the scene, the occupants of the Parker home let out a cheer of joy. Kline believed that the blacks were reinvigorated by the presence of Hanway, their leader. In truth, the shout of joy was in response not to Hanway’s appearance, but the growing crowd of armed blacks come to the Parkers’ defense. In addition, Kline says that it was just after Hanway and Lewis went up to the assembled blacks that the violence erupted resulting in Gorsuch’s death. Kline believed that Hanway gave the blacks the signal to attack the posse. Supporting Kline in these assertions was Harvey Scott, the same black man who had helped to identify the others present at Parker’s. The defense poked holes in this testimony, noting how Hanway had actually helped shield Dr. Pearce and Joshua Gorsuch as they were fleeing from the mob, hardly the actions of an abolitionist leader bent on insurrection against slaveholders.

In addition, when the defense cross-examined Harvey Scott, the young man admitted on the stand that everything he had stated before was perjury. Scott admitted he had been arrested in the chaos that followed the resistance but had not even been at the house. Kline identified him as one of the men present even though he was not. Kline threatened Scott, telling him if he did not assist him he would suffer the same fates as the others and so Scott committed perjury to protect himself. This revelation on the stand caused an audible laughter from the assembled crowd. Here was one of the government’s key witnesses admitting that he was coerced into testifying falsehoods. Despite this setback, Ashmead and the rest of the prosecution continued with their case of treason. They attempted to show that the entire existence of Parker’s mutual protection organization (which they unsurprisingly attributed to Hanway and the other white residents for encouraging) was evidence of open treason and a group determined to levy war against the laws of the U.S. When the time came for the closing arguments, the prosecution was sure to mention the dire predictions for the future should the verdict fail to uphold the law, “Bigots, fanatics, and demagogues have endeavored to stimulate the populace to illegal and monstrous acts.” The prosecution warned that if agitators such as Castner Hanway were not stopped they, “would bring upon this country of ours civil war, disunion, and all that is horrible.”

On December 16, 1851, the jury for the Christiana treason case retired from the trial room in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. After only fifteen minutes of deliberation the jury reconvened in the courtroom and brought a verdict of “not guilty” in Castner Hanway’s case of treason. Likely prepared for this outcome, U.S. Attorney Ashmead declared that the government would not try Hanway for the lesser charges against him. Hanway was a free man once again. All other treason charges against the remaining defendants were dropped.

Justice

While Hanway and the remaining white defendants were set free, the bulk of the black defendants were still facing state charges of riot and murder. When a group of nine men were transferred back to Lancaster County on December 31, 1851, the local district attorney found the evidence presented was insufficient to warrant their detention and trial. The nine men were released that same day. In January of 1852, the lawyers for the remaining defendants charged with rioting and murder being held in Philadelphia filed suit against Marshal Henry Kline for making false statements under oath. This indictment gave the lawyers some bargaining power. On January 16, a settlement was made where neither the charges against Kline nor against the remaining defendants would be prosecuted by the state. The remaining Christiana prisoners were released and returned home.

Peter Woods, another participant in the Christiana Resistance, was imprisoned but eventually let go. This photograph of Woods is taken about 60 years after the event.

One last case relating to the Christiana Resistance was brought up in January of 1852. This time it was a federal case against Samuel Williams, the black abolitionist who followed Gorsuch’s party to Christiana and warned the region about the kidnappers. According to his defense lawyer the case against Williams was taken up merely to “avoid the implication of imbecility” after the government’s loss in the treason cases. Williams was charged with a federal misdemeanor for obstructing the fugitive slave law. This was the same punishment that Kline had threatened Elijah Lewis and Castner Hanway with when they failed to assist him at Parker’s. Kline was called as the chief witness against Williams and, though the case was fairly straight forward from a legal perspective, Kline’s tarnished reputation worked against him. The fatigued nature of the Christiana trials and the fact that one of Williams’ defense lawyers was the son of the presiding judge in the case, resulted in Williams being found not guilty. The Christiana Resistance ended with no one being held accountable for the death of Edward Gorsuch or the defiance of the Fugitive Slave Law.

Despite the verdicts of not guilty in the Christiana cases, the warnings of Civil War did not come to fruition at that time. The gambit that the Fillmore administration enacted had worked out. The Federal government had come to the aid of the Southern states and had charged treason against those who defied the Fugitive Slave Law. Though the Southern states were furious at the outcome and continued to speak out against the traitorous northerners who defied the law, the process had appeased them to some degree.

For abolitionists the Christiana Resistance and subsequent trials provided a surprising windfall of new sympathizers to their cause. William Still, the black abolitionist leader in Philadelphia, wrote that the Christiana case was, “doubtless the most important trial that ever took place in this country relative to the Underground Rail Road passengers, and in its results more good was brought out of evil than can easily estimated…The tide of public sentiment changed – Hanway, and the other ‘traitors’ began to be looked upon as having been greatly injured, and justly entitled to public sympathy and honor…”

Frederick Douglass likewise wrote that the affair at Christiana, “inflicted fatal wounds on the fugitive slave bill. It became thereafter almost a dead letter, for slaveholders found that not only did it fail to put them in possession of their slaves, but that the attempt to enforce it brought odium upon themselves and weakened the slave system.” Or as William Still more succinctly put it, after Christiana, “…slave holders were taught the wholesome lesson that the Fugitive slave Law was no guarantee against ‘red hot shot’.

Canada

The aftermath of the trials did nothing to alleviate the dangers faced by William Parker and his men. They knew that if they returned to the United States they would face punishment. So, the three men began building lives for themselves in Canada. Eliza Parker and Hannah Pinckney joined their husbands two months after the resistance. They had been arrested and released twice, and Eliza had put her children under the care of her mother and other neighbors. Upon learning that her former master had been made aware of her location, Eliza fled north without her children to avoid capture. In time William and Eliza Parker’s three children would join them in Canada. The Parkers, Pinckneys, and Abraham Johnson took up residence in a black community in what is now North Buxton, Ontario.

Known then as the Elgin settlement, the region had been settled in 1849 by a Presbyterian minister named William King. Rev. King was an Irishman by birth but had immigrated to America and had married into a Louisiana slaveholding family. After the death of his wife, Rev. King inherited a number of her slaves. After doing some missionary work in Canada, Rev. King came up with the idea of starting a community of black pioneers and former slaves in Canada. Starting with his own former slaves, the colony grew quickly over the next few years. Within three years of its founding, over 130 families had settled in Buxton, including the Christiana fugitives. While Rev. King maintained a place of honor among the residents, all of the day-to-day operations of the community were enacted by the black citizenry. When Frederick Douglass visited the colony in 1854, he held it to be one of the greatest proofs that the black man, “can live and live well, without a master, and can be industrious without the presence of the blood-letting lash to urge him on to toil.” Out of nothing but 9,000 acres of forest, in just over four years the residents of Buxton had built themselves a school, church, store, hotel, blacksmith shop, pearl ash factory and dozens of family homes. They cleared and planted rich fields of corn, grass and grain and boasted over seven hundred residents. On his own 50 acre plot of land, William Parker built a home for his growing family.

Even in Canada, William Parker’s fame followed him. A 1856 editorial in The Provincial Freeman described him as “A Noble Fellow” and that “a hundred such villains as Kline of Pennsylvania, would be made to tremble and quake before the masterly eye of such a man as Mr. Parker.” When visiting Canada to give speeches on abolition, Frederick Douglass stated that Parker and “his noble band…who defended themselves from the kidnapper with prayers and pistols, are entitled to the honor of making the first successful resistance to the Fugitive Slave Bill.”

Parker’s fame eventually brought him to the attention of a 38 year-old white abolitionist who was looking for black recruits to take part in plot against slaveholders. The man wrote a letter on August 27, 1859 to another member of the plot detailing having met a man of great interest in Buxton. Writing in code due to the sensitive nature of their plot, the recruiter never gives Parker’s name but the description provided perfectly matches the hero of Christiana:

“At (‘B-n’) I found the man, the leading spirit in that ‘affair,’ which you, Henrie refered to. On Thursday night last, I went with him on foot 12 miles; much of the way through new paths, and sought out in ‘the bush’ some of the choicest. Had a meeting after 1 o’clock at night at his home. He has a wife and 5 children; all small, and they are living very poorly indeed, ‘roughing it in the bush,’ but his wife is a heroine, and he will be on hand as soon as his family can be provided for. He owes about $30; says that a hundred additional would enable him to leave them comfortable for a good while.

After viewing him in all points which I am capable of, I have to say that I think him worth in our market as much as two or three hundred average men, and even at this rate I should rate him too low. For physical capacity, for practical judgement, for courage, and moral tone, for energy and force and will, for experience that would not only enable him to meet difficulty, but give confidence to overcome it, I should have to go a long way to find his equal, and in my judgement would be a cheap acquisition at almost any price.

I shall individually make a strenuous effort to raise the means to send him on.”

The author of his letter was John Brown, Jr. and he was recruiting for his father’s upcoming plot to start an armed slave revolt by raiding the arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. The ill-fated raid occurred two months later but, despite Brown’s glowing endorsement of Parker and how hard he would work to make him a part of his father’s plan, there is no further evidence that Parker took part in this event. Perhaps Brown could not come up with the money needed to bring Parker into the fold. Regardless, it is eerily coincidentally that William Parker was involved, in some manner, in two of the most notable slave rebellions in the pre-Civil War years.

Life and Death

The issue of slavery finally came to a head in the United States and Civil War broke out in 1861. Abraham Lincoln’s issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation in January of 1863, granted African-Americans the ability to enlist and fight on the side of freedom. Of the three men who took up residence in Buxton, it was Alexander Pinckney who answered the call to fight on the side of liberty. The man who was once fearful at the sight of a slave catching posse in his yard travelled south and enlisted in March of 1863. He joined the most famous of the colored regiments, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, where he was promoted from private to sergeant. Alexander Pinckney was one of the soldiers who took part in the famous Battle of Fort Wagner, which is well-known today due to it being the subject of the 1989 film Glory. Pinckney survived the unsuccessful charge on Fort Wagner and when the Fort was finally abandoned by the Confederates in September of 1863, Pinckney was assigned as one of the permanent boatmen who ferried men between the fort and the mainland. Pinckney was discharged from the service in August of 1865 and subsequently moved with his wife Hannah to Michigan where their trail runs cold.

The ultimate whereabouts and fates of Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, George Hammond, and Joshua Hammond, the four men who set all of these events in motion when they stole grain from Edward Gorsuch in 1849 is unknown. They are said to have escaped up to Canada following the incident at Parker’s farm.

Dickinson Gorsuch survived his near fatal wounding and returned home to Maryland. For the rest of his life, his side would be pitted from the shotgun blasts he received from Alexander Pinckney. He lived and worked on the family farm until his own death in 1882.

Abraham Johnson, the man who vowed to “fight till I die” when Gorsuch’s party surrounded his home lived out the remainder of his life in the Buxton settlement, living on a plot of land right next to the Parkers. He married, had a family and his descendants continued to live on his original farm until just a few years ago.

After an inquest was held, the body of slain slaveholder Edward Gorsuch was transported back to Maryland. On September 14, three days after his death, Edward Gorsuch was laid to rest in a small private cemetery on his Baltimore County property. Dickinson was not present at his father’s funeral as he was still recovering at the Pownall’s farm in Christiana. The funeral was conducted by Gorsuch’s eldest son, Rev. John Gorsuch. The cemetery the elder Gorsuch was placed in was bounded on all sides by a low stone wall with no door or gate. A 1911 book commemorating the Christiana incident contained this single image of the small cemetery:

Through a great deal of sleuthing it was discovered that the cemetery still stands today. Surrounded by trash and overgrown with vines, weeds, and other thorny plants, the cemetery is located next to a private home only a quarter of a mile away from the tavern from which the slave catcher planned his ill-fated journey.

The cemetery today, as in 1911, contains only three small headstones that are almost impossible to find among the brush.

It is said that the center stone, belonging to Edward Gorsuch is marked by his initials E.G. but the current state of the cemetery made it impossible to see these markings.

The Parkers

William and Eliza Parker spent many happy years together in Buxton. By 1871, they had 10 children together, seven of which had been born in Canada. During their time in the Elgin settlement William began taking classes at the local school and he possibly learned how to read and write at that time. As early as 1858, there was interest in publishing William Parker’s life story. After the Civil War had ended, Parker was assisted by other educated black men to pen the story of his life. Titled, The Freedman’s Story, Parker’s biography was published in two parts in the February and March 1866 issues of the Atlantic magazine. Though some later historians questioned the authorship of this piece, certain details contained in the narrative could have only come from Parker himself. Others may have assisted Parker in improving the manuscript, but the story is definitely Parker’s.

In the summer of 1872, over twenty years after the event that caused him to flee, William Parker returned to Christiana for the first time. He visited his old home which still stood and was entertained by many of his old friends who still resided in the area. Among those he visited with were Peter Woods and Samuel Hopkins, two men who had been present at the resistance two decades before. Parker was the guest of honor at the commencement of Lincoln University, a black secondary school and college situated some 15 miles south of Christiana. The school had been founded in 1854 partly due to the attention the Christiana Resistance had brought upon the plight of blacks in Pennsylvania. It appears that Parker remained in Christiana throughout the summer as he was also present at a meeting of the black citizens on August 30, 1872 regarding the upcoming Presidential election.

It appears that sometime during Parker’s visit to Christiana in 1872, he became reacquainted with a woman he had known twenty years before named Martha Simms. Martha’s husband Henry Simms had been one of the men present at the resistance and was later imprisoned as one of the 38 indicted for treason. He, like the others, was released and returned home. Henry Simms died not long before Parker’s return to Christiana.

Apparently William Parker became infatuated with the widow Simms during his visit and the two ran off together. Peter Woods was under the impression that Parker was a widower himself and took Martha Simms back with him to Canada. However, Eliza Parker was very much alive and caring for the couple’s ten children whose ages ranged from 26 down to 1. William Parker and Martha Simms did not go up to Canada, but instead settled in Kenton, Ohio, some 480 miles from Christiana and 200 miles from Buxton. According to descendants of Abraham Johnson, when William Parker made his 1872 trip down to the United States, he was never heard from again by Eliza or their children. For the rest of their days, they assumed William had been the victim of foul play due to his notoriety.

Living in Kenton, William Parker was a member of the Masonic order and was known to his neighbors to have been an agent of the Underground Railroad prior to the Civil War. It does not appear that anyone connected him with the famous William Parker of Christiana fame. William Parker and Martha Simms lived as husband and wife for almost 20 years.

William Parker’s death came on April 14, 1891, when he was about 70 years old. He was buried in Kenton’s Grove Cemetery. Though William Parker has no stone of his own in his Grove Cemetery plot, there is a unique marker which bears his surname. In 1880, two of Martha Simms’ daughters from her marriage with Henry Simms died within six months of each other. They were buried in a plot in Grove Cemetery and shared a grave stone. William Parker was buried next to these women upon his death in 1891. When Martha Simms Parker died in 1919 she too was buried in the plot. On the stone which contains the names of Martha Simms daughters, there is the faint inscription of the name “PARKER”.

The memorial to Martha Simms’ daughters in Grove Cemetery, Kenton, Ohio which contains the Parker surname. Photo courtesy of Peyton J. Ennis

Eliza Parker was perhaps the true hero of the Christiana Resistance. As a young woman, Eliza had the strength to escape from her especially bitter enslavement to start a new life in Pennsylvania. She gave birth to, and cared for, three children while her husband put himself in danger running his mutual protection organization. When the battle for freedom arrived at her door, it was Eliza who saved them all by raising the alarm even in the face of bullets directed at her. When her husband had to make his escape, she stayed behind and faced imprisonment in his place. It was only the certainty of a return to slavery that caused her to make her own escape, temporarily leaving her children behind. She braved a pioneer life in Ontario, helping to build a home out of the unfamiliar forest and land. And when her husband disappeared in 1872 never to be heard from again, she persevered and raised her ten children alone. Eliza Parker died on May 28, 1899 but as late as 1969, she was still fondly remembered by her aged grandchildren. In 2013, one of her descendants erected a plaque next to her faded grave in Buxton. The plaque notes that Eliza was “a heroine in the tumultuous time preceding the Civil War”.

Eliza Ann Parker’s Grave in North Buxton, Ontario. Photo courtesy of Douglas Gammon and ckacemeteries.ca

Remembering