My friend Carolyn Mitchell alerted me to this lot currently up for bid from Raynor’s Historical Collectible Auctions. It is a collection of materials from a Civil War veteran by the name of Patrick Tighe.

The lot includes some of Tighe’s possessions including his Grand Army of the Republic medals and badges, his pocket watch, a memorial ribbons for President Lincoln, and also some CDVs and books which are not pictured. The most interesting part of the lot, and the likely reason that the starting price is $3,500, is the large piece of wood that has a replica wanted poster affixed to it. According to the lot description the piece of wood is from the Garrett house, on the porch of which John Wilkes Booth died on the morning of April 26, 1865.

The lot description states, in part:

“Patrick Tighe, (The CW Date Base spells it TIGH) at age 38, enlisted September 3, 1864 at Avon New York, mustering into Company H, 16th NY Cavalry and mustered out May 29, 1865. Tighe was a member of of the detachment of the 16th New York that had the distinction of killing Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth and apprehending accomplice David Herold. Post war, Tighe joined GAR post #235, Avon New York. The impressive 13″ x 18” barn wood has two period labels, “GAR Post 235, H.C. Cutler, Avon New York” where Tighe was a member and the donor of the piece. The second label “This barn siding was from the Garnett House where John W. Booth was killed”. When the Post closed, c1930, the siding was returned to the Tighe family. The siding has a reproduction April 20, 1865 Reward Poster for the Assassins, 11″ x 15″…”

Carolyn knew this lot would pique my curiosity due to my interest in the death of Booth at the Garrett farm. But the name of Patrick Tighe did not ring a bell. With some research I confirmed that Pvt. Tighe was a member of the 16th NY Cavalry. As we know, a detachment of the 16th NY were the ones who tracked down John Wilkes Booth. However, when I consulted a list of the soldiers of the 16th NY present at the Garrett farm when Booth was shot and killed, Tighe’s name is not included. Nor did Tighe receive any reward money for the capture of Booth. Tighe wouldn’t be the first member of the 16th NY Cavalry to later claim to have been at Booth’s death even though he wasn’t. Several others who were part of the 16th NY but not at the Garrett farm embellished and lied about their role in hunting down Booth in the decades that followed. I was ready to chock up Patrick Tighe’s piece of Garrett farmhouse wood as yet another fake, just like the replica wanted poster attached to it.

But I decided to dig a little bit more on Mr. Tighe. Though Tighe never received any money for Booth’s capture, I was surprised to find that he did make an application to the government for a share of the reward. Here are the microfilm scans of Tighe’s official application for reward money followed by a transcription:

“Avon, Dec. 8th 1865

To/ The Adjutant General of the Armies of the U.S.Your petitioner, Patrick Tighe private in Co. H. 16th Cavalry N.Y.V humbly represents that he was one of the Cavalry detailed to arrest, seize, and if necessary kill the Assassin of Abraham Lincoln, and his accomplices.

As the Government has set apart a sum to reward those engaged to secure such arrest, I hereby put in my claim for such part of the reward as I may be entitled to – being myself, Patrick Tighe aforesaid, one of party detailed. My residence is Avon, N.Y. and the Commander of my detachment was Lieutenant Peter McNaughton, then in command of Co. H. 16th Cavalry N.Y.V.

An early answer from your department would much oblige.Yours with high Consideration

Patrick Tighe”

I was a bit perplexed by this reward application. It is carefully worded to imply that Tighe was with the group that arrested Booth and Herold, but it doesn’t explicitly state that. It just states that Tighe was detailed with attempting to find the assassins. Hundreds of men were put in the field to search for Booth and his accomplices and many of them filed reward claims only to be denied, as Tighe was. But his ongoing connection to the 16th NY was intriguing.

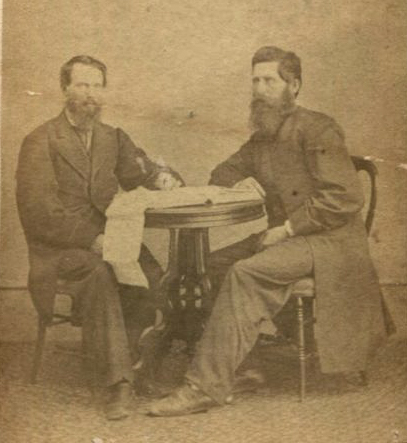

I contacted Steve Miller who is THE expert on Boston Corbett and the 16th NY. He stated Tighe’s name didn’t ring any bells but the commander Tighe mentioned, Lt. Peter McNaughton, did. Steve reminded me about how different detachments of men from the 16th NY Cavalry were all over the place during the manhunt. John M. Lloyd, the renter of Mary Surratt’s tavern who became a key prosecution witness against her, was arrested by men of the 16th NY. On April 21st, Dr. Mudd was arrested by Lt. Alexander Lovett of the Veteran Reserve Corps. accompanied by Lt. William Farrell (and men) of the 16th. At the same time Booth was shot and killed a separate detachment of men from the 16th NY claimed to have been on his trail and only four miles from the Garrett farm. Lt. Peter McNaughton, in his own reward application, claimed to have been one of the men present at Dr. Mudd’s arrest.

McNaughton was also one of the leaders of what Steve calls the second Garret farm patrol. The first Garrett farm patrol is the one we are familiar with. Those were the 26 guys led by Lt. Edward Doherty, along detectives Everton Conger and Luther Baker, who tracked and killed Booth at the Garrett farm. All of those participants received a share of the reward money. After Booth’s body was transported by these men up to Washington, it was determined that a second patrol was needed to return to the northern neck of Virginia in order to retrace and determine Booth’s route through the region. This second Garrett farm patrol consisted of 20 Cavalry men of the 16th NY guided by detective Luther Baker, who had been present at Booth’s death. The soldiers were commanded by Lt. McNaughton.

The group was also accompanied by a reporter for the New York Herald, a man by the name of William N. Walton. How Walton managed to gain access to this detachment is unknown. Late on April 29th, the group set out from D.C., steamed south, and then headed overland to the Garrett farm. They arrived back at the Garrett farm just before sundown on April 30th. Several members of the detachment remained at the Garrett house overnight as did William Walton. During this time, Walton sketched the Garrett house and the remains of the burned down barn. These sketches would later be turned into woodcuts and published in the May 20 edition of Harper’s Weekly.

As the bulk of the second Garrett farm patrol rested at the farm, some men were ordered out in search of Willie Jett, the Confederate private who had dropped John Wilkes Booth off at the Garrett farm in the first place. Jett had originally been arrested by the first Garrett farm patrol. He was the one who led the soldiers from Bowling Green back to the Garrett farm where Booth was hiding out in the barn. Jett witnessed Booth’s death and then traveled northward with Luther Baker, a couple soldiers, and Booth’s body. However, during the trek north through Virginia, Luther Baker released Jett and allowed him to go home. When the party arrived in D.C., the Secretary of War was angry at Baker for releasing Jett and immediately ordered his arrest.

Recapturing Jett was a key part of the second Garrett farm patrol’s mission. Earlier on April 30th, Mr. Garrett had visited Willie Jett in Bowling Green and attempted to get Jett to sign a statement attesting that he had brought Booth to the farm under an assumed name. Jett had decline to sign the statement. When the troopers attempted to find Jett in Bowling Green, they discovered he had departed. Eventually they hunted him down to the home of his father in Westmoreland County and placed him under arrest.

Over the course of the next couple of days, the second Garrett farm patrol retraced Booth and Herold’s movements backwards. They spoke with several people who interacted with the fugitives during their escape and arrested several of them. They seemed to be especially keen on arresting folks with the first name of William. In addition to Willie Jett, the patrol rounded up William Rollins, the fisherman in Port Conway who had agreed to take Booth and Herold across the Rappahannock River before Jett and the other two Confederates arrived, William Lucas, the free Black man that Booth essentially evicted from his home after being turned away by Dr. Stuart, and William Bryant, the man who transported the fugitives from Mrs. Quesenberry’s to Dr. Stuart’s home of Cleydael. The group also interviewed Mrs. Quesenberry and her daughter who had spoken with David Herold after the pair made landfall in Virginia.

On May 3rd, the second Garrett farm patrol arrived back in D.C. and deposited their detainees in the Old Capitol Prison. They also passed along the information they had gained from their Virginia sojourn. The next day, William Walton published a lengthy article in the New York Herald documenting what he had learned about the escape route of John Wilkes Booth as a result of his trip with the second Garrett farm patrol.

From Walton’s article, it appears that the second Garrett farm patrol was very successful in establishing JWB’s escape route through Virginia. However, it was decided by the authorities in Washington that the second patrol had not done an adequate job in acquiring all of the witnesses that were needed. As a result, a third patrol of men from the 16th NY was quickly assembled in order to make a return trip. Detective Baker did not join this group and it was, instead, solely led by Lt. McNaughton who was now familiar with the territory. Reporter William Walton later wrote about this third trip but it’s difficult to tell if he was speaking from his own firsthand experiences with this third patrol or if he was relating things that were told to him by Lt. McNaughton, whom he appears to have befriended.

The third group of men from the 16th NY Cavalry departed D.C. late on May 4th. Rather than going to the Garrett farm, however, this detachment was tasked with finding and arresting Absalom Bainbridge and Mortimer Ruggles, the Confederate soldiers who ran into Booth with Willie Jett at the Rappahannock River. The posse traveled to Friedland, the home of Confederate General Daniel Ruggles, in King George County, Virginia. There they found and arrested Mortimer Ruggles, who was Gen. Ruggles’ son. Friedland plantation was also the home of Absalom Bainbridge as his mother and Mortimer Ruggles’ mother were sisters. Bainbridge was not at the home when Lt. McNaughton and his men got there but, according to Walton’s account arrived back about a half hour later. The two cousins were transported and placed on a waiting steamer while the group then traveled to Dr. Stuart’s home of Cleydael. While the second Garrett farm patrol had interviewed Dr. Stuart a few days earlier, they had not taken him into custody. This time, however, he was compelled to come with the men. On May 6, the whole detachment, with their three prisoners in tow, arrived back in D.C.

- Absalom Ruggles Bainbridge (1890)

- Mortimer Bainbridge Ruggles (1897)

- Dr. Richard Stuart

As stated, William Walton wrote about this third expedition for the New York Herald. You can read that article here.

Now that we have a handle of the different patrols of 16th NY Cavalry that visited Virginia, let’s return to the subject of Patrick Tighe and his alleged piece of wood from the Garrett house. As we have established, Pvt. Tighe was not one of the soldiers of the 16th NY Cavalry present in the first Garrett farm patrol that cornered and killed John Wilkes Booth on April 26, 1865. The third patrol which traveled into Virginia on May 4th did not stop at the Garrett farm but stayed in King George County the whole time. Therefore, the only way for this relic to be genuine and to have been personally acquired by Pvt. Tighe is if he was a member of the second Garrett farm patrol that arrived at the farm on April 30th.

The problem is, there’s no way to prove that Tighe was part of that patrol. The only reason the specific members of the original Garrett farm patrol are known is because of the fight for the reward money. Lt. Doherty made a list of the men under his command in order to ensure each one received their fair share. There are no rosters of the second or third group of 16th New Yorkers who traveled into Virginia during the subsequent visits. Patrick Tighe’s application for reward money is vague. He might have been with Lt. McNaughton and the second Garrett’s farm patrol, or he might have been with him at the arrest of Dr. Mudd or another part of the manhunt. Without more information, we can never be sure.

While the relic being genuine is an intriguing possibility, I’ll admit that the size of the wood piece and the corresponding lot description gave me some pause. Why would the Garretts allow a solider to take such a sizable piece (13″ x 18″) of wood from their house, which was their main residence and undamaged from the fire that consumed their barn? The Garretts continued to reside in the farmhouse for decades after Booth’s death and while a sneaky soldier might be able to break off a small relic, it seems improbable that Tighe could have walked off with a large piece of the house without any of the Garretts noticing and objecting. The phrasing of the lot description is also confusing as it is refers to the relic as “barn wood” from the “Garnett [sic] house”. Why would the siding of the house be called barn wood?

It appears that there are some quality control issues over at this auction house. I zoomed into the small label affixed to the wood. It’s a bit pixelated as the original image isn’t all that big. Still, in my opinion, this label reads, “This barn siding was from the Garrett barn where John W. Booth was killed.”

The wood relic coming from the remains of the burned down barn makes more sense than a piece pried off of the Garrett house. I wish the auction house had more images of the wood piece. It would be interesting to see if it bears any evidence of having been charred or blackened.

At the end of the day, however, this lot is far too pricey for a centerpiece item whose authenticity is only a “maybe”. Two of the claims in the lot description, that Tighe was there when Booth was killed and that the wood came from the Garrett “house” have been disproven. While it’s still possible that the piece is genuine and something that Pvt. Tighe acquired as a member of the second Garrett farm patrol, without further evidence, such claims would be impossible to prove. Still, this relic served as an illuminating jumping off point to learn more about the different patrols of the 16th New York Cavalry that were sent into Virginia in order to retrace the steps of John Wilkes Booth. And, hey, if anyone wants to purchase the lot before it ends on August 27th, I certainly wouldn’t say no to a gift.

Many thanks to Carolyn Mitchell for making me aware of this auction item and to Steve Miller for sharing his picture of Lt. McNaughton and his expertise with the 16th NY Cavalry with me.

Recent Comments