Update: This playbill sold for $85,000. After adding the 25% Buyer’s Premium, the total cost of the playbill was $106,250. At the same auction, a John Wilkes Booth wanted poster sold for $105,000 ($131,250 with Buyer’s Premium).

This Saturday (9/28/2024), R.R. Auctions is set to sell an iconic and rare Lincoln assassination-related item: a Ford’s Theatre playbill from the night of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination.

While there are a plethora of period reprints and modern replicas of assassination playbills, genuine playbills are very elusive things, and examples rarely come up for auction. One of the most recent sales of a genuine Ford’s Theatre assassination playbill was by Christie’s auction house. In 2003, they sold a second issue playbill (those included an added section near the bottom advertising the planned singing of “Honor to Our Soldiers”) for $31,000.

Normally, I don’t post about all the interesting items that come up for auction, but this playbill is different. If you check out the auction listing for this playbill, you might notice a familiar name:

It turns out I have a little history with this specific playbill.

One of my earliest posts on this blog concerned the assassination playbills and how you can tell real playbills from fakes and replicas. In addition to regularly being asked my opinion on possible “new” John Wilkes Booth photographs, I have been sent pictures of a few playbills in the past. Each time I have had to break it to people that they have a reprint or a forgery. Last year, I received an email from a couple who had read my post and were hoping to get my thoughts on a Ford’s Theatre playbill that they owned. I happily agreed to take a look at it while mentally preparing to let down yet another disappointed replica owner.

As I looked at the pictures sent me, I was surprised to see that I was not able to instantly discount the playbill. I scoured over the small details of typography, spacing, and printing, and each seemed to align with genuine bills. I sent some follow-up questions to the owners, not tipping my hand that I was getting excited by what I was seeing. I asked about the provenance behind the piece and set to work investigating that. After a few days of research, I came to the astonished conclusion that this was a genuine first-issue playbill for Our American Cousin.

In my excitement, I went about writing up a research report for the owners explaining my conclusions. Never one for brevity, that report ended up being nine pages long. In advance of the sale on Saturday, I asked the owners if I could publish my report for them on this blog. They agreed, so I have published my report below. For the privacy of the current owners, I have redacted their names from the report and replaced them with John and Jane Doe.

Report on an April 14, 1865 “Our American Cousin” playbill owned by John and Jane Doe

By Dave Taylor

LincolnConspirators.com

Introduction: On April 25, 2023, I was contacted through my website, LincolnConspirators.com, by Jane Doe. Several years ago, I published an article on my site discussing the different playbills issued by Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. Given my experience in analyzing authentic and fraudulent Lincoln assassination playbills, Jane asked me if I would look at a playbill owned by her and her husband, John, and give my opinion of it. I accepted and was provided with several images. The following is a report of my research process and ultimate conclusions regarding the playbill in question.

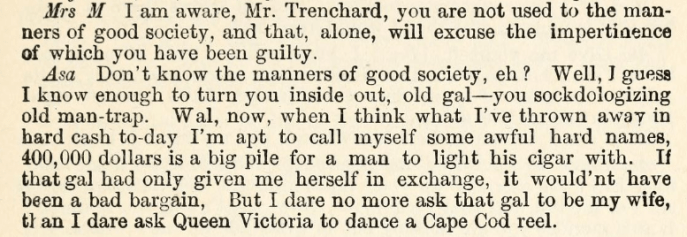

Background: Abraham Lincoln was shot by assassin John Wilkes Booth on the evening of April 14, 1865, while the President and his party were attending a performance at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. The play they were attending was a comedy entitled Our American Cousin, with actress Laura Keene as the lead star. After the shooting of Lincoln, the theater was shut down and would not see another performance for over 100 years. Very shortly after the tragedy, there was a demand for playbills of the last play Lincoln saw. This demand led to a secondary market of replica and forged playbills. Some of the fraudulent bills were so convincing that they even managed to fool those who were present at the assassination into swearing to their authenticity. In 1937, researcher Walter C. Brenner privately published a monograph entitled The Ford Theatre Lincoln Assassination Playbills: A Study. Brenner analyzed several variations of bills housed in different collections in an attempt to definitively determine which version or versions of playbills were actually printed and present on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. Through his research, Brenner was able to locate proven examples of legitimate assassination playbills in the Harvard Theatre Collection. He published his findings and included a chart noting the small details that can prove or disprove a suspected assassination playbill. In 1940, Brenner published a small supplement to his original research, reproducing an 1898 article that narrated the history of the playbills and why there were two different, but both equally legitimate, versions of playbills used at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865. During my own analysis of the Doe playbill, I heavily referenced Brenner’s work.

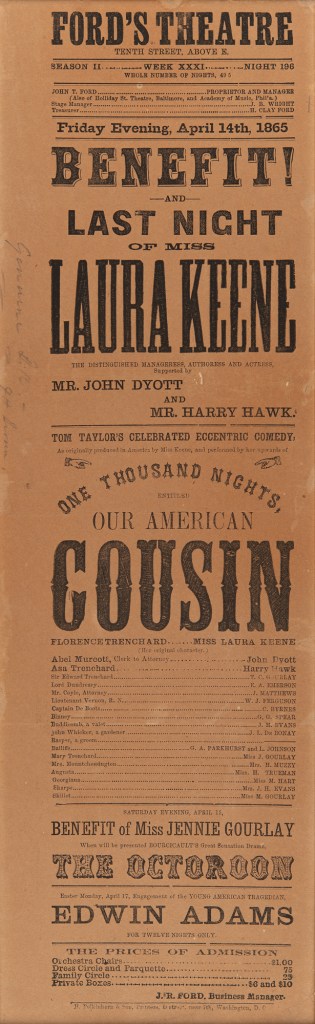

Visual Analysis: The Doe playbill measures approximately 18.5” long and 5.5” wide. It is currently matted inside of a frame with a handwritten piece of provenance below it (Fig. 1).

On the left edge of the bill near the name of Laura Keene is written in pencil the words “Genuine bill – [illegible] J H Brown” (Fig. 2).

The paper of the bill is browned. There are some discolorations and mild defects around the visible edges. A circular shaped defect about ¼” in size can be seen about 7 inches from the top near the name of John Dyott (Fig. 3).There is evidence that the bill was previously folded with a light horizontal crease through the line containing the text “Buddicomb, a valet” (Fig. 4).

Minor discoloration can be seen in other places. Still, overall, the bill is very clean, albeit browned from prior display. The bill was not examined out of the frame.

Compositional Analysis: At first glance, this bill represents an example of the first issue playbill for April 14, 1865. Bills of this sort were initially the only bills in production by printer H. Polkinhorn and Son in preparation for the evening’s show. After it was ascertained that President Lincoln was going to be attending the theater that night, it was decided that the singing of a patriotic song that was planned for the following evening was to be included. As a result of this change, the type of the printed bill was adjusted to include a paragraph about the now-planned singing of “Honor to Our Soldiers.” The Doe bill does not contain this paragraph, thus making it a possible first-issue playbill.

The Huntington Library in San Marino, CA, owns a genuine first-issue playbill for Our American Cousin. They have digitized this playbill at a high resolution, and it is available to view here: https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p16003coll6/id/5034/rec/1 Using this bill as an example, I then conducted a detailed comparison between it and the Doe playbill.

During my comparison, I looked for the different details documented by Brenner as those present on a genuine first-issue playbill, all of which are borne out on the Huntington playbill. Among those details are:

- A space between the digits 9 and 5 in the text “NUMBER OF NIGHTS, 49 5”

- The condition of the final E in the name of “LAURA KEENE”

- The condition of the final R in the word “MANAGER”

- The alignment of the letter H in the name “H. CLAY FORD”

- The alignment of the letter S in the words “Supported by”

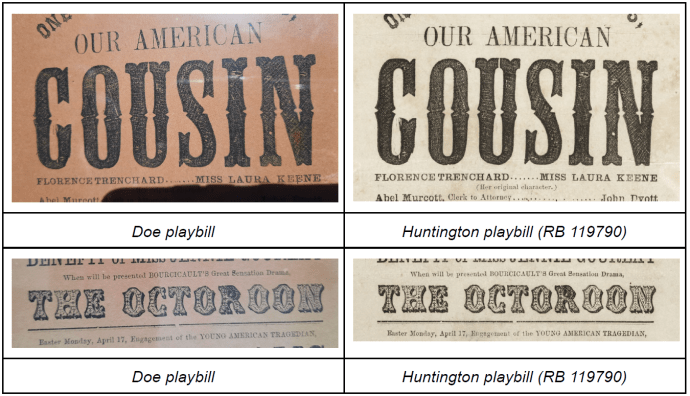

- A small interior misprint on the letter C in “COUSIN”

- A small circular defect on the letter N in “COUSIN”

- The spelling of “Sensation”

- The word “Chairs” after the word “Orchestra”

- Several breaks in the horizontal lines separating different blocks of text

For each point of comparison, I found that the Doe playbill matched the details of the Huntington playbill. Everything was compositionally correct and in the right place to match a genuine first-issue bill.

I then looked for evidence of duplication. There have been other bills that I have examined in the past that have had the correct content, but they have distinct evidence that were merely copies of a legitimate bill. When copies of bills are made, there is a distinct drop in quality and detail. This is very noticeable in the font of “THE OCTOROON,” where the small details are lost. In addition, duplication removes the minor irregularities present during the original printing process. In addition to examining the font of “THE OCTOROON,” I requested and was provided with close-up images of the word “COUSIN” so that I could assess the natural deviations in this boldly printed word.

In my opinion, this bill does not show signs of being a duplicate. The fine details are present and consistent with an original printing, not a copy done by modern means.

Based on my visual and compositional analysis, I believe that the Doe playbill is a genuine first issue from April 14, 1865. It matches all points of comparison as laid out by Walter Brenner in his study of genuine assassination playbills, and there is no evidence of the bill being a period of modern reproduction.

Provenance Analysis: From my communications with Jane, I learned that this playbill has been in her husband’s family for over a hundred years. Mr. Doe’s great-grandfather was named Frederick S. Lang, the owner of a sizable Lincoln collection. According to Jane, this playbill and some other materials are what remains of the former Lang collection of Lincolniana.

In June of 1919, C. F. Libbie and Co. auctioned off what was advertised as a “Lincoln Collection formed by Frederick S. Lang, Boston.” Mr. and Mrs. Doe still retain two copies of this auction catalog. A digitized version of the catalog, housed on the Internet Archive, can be viewed here: https://archive.org/details/catalogueoflinco00libb. In examining the catalog, we find the following lot description:

“1129 Play Bill. Ford’s Theatre, April 14, 1864[sic]. One of the original play bills, first issue. Neatly matted in a narrow oak frame. Folio. This is one of the original play bills purchased from the Estate of John B. Wright, who was stage manager, by J. H. Brown.”

Given the presence of the playbill with a descendant of Frederick Lang today, it would appear that this lot did not sell in 1919. Perhaps the misprint in the auction catalog of 1864 rather than 1865 caused it to fall under the radar.

In addition to the playbill’s entry in the 1919 auction catalog, the bill is framed alongside a small handwritten note. This note is faded and brown but is still legible. It states, “I purchased this Bill from the Estate of John B. Wright who was Stage Manager / J H Brown”

Further information about the bill is included in a transcript of a circa 1909 typewritten essay or article about Frederick Lang’s collection. This transcript is owned by Mr. Doe. Jane provided a picture of a page from this essay that mentions the playbill. The text is as follows:

“occupying[sic] a prominent place on the wall is the exceedingly rare, genuine play-bill of Ford’s Theatre, April 14th, 1865 the night of Lincoln’s assassination. The attraction was Laura Keene, in Our American Cousin, and in the cast were many players well known in Boston, among them being W. J. Ferguson, Harry Hawk, and Geo. G. Spear. This play-bill was obtained from the collection of the late J. H. Brown, one of the best known theatrical collectors in the country. It is accompanied by his affidavit that it was purchased from the estate of J. B. Wright, the stage manager of Ford’s Theatre at the time of the tragedy. Mr. Wright was well known in Boston, as he was for many years connected with the National Theatre of this city, as stage manager and lessee. Mr. Lang also has a copy of the fac-simile of the genuine bill, copyrighted 1891, with affidavit by R. O. Polkinhorn who was pressman at the time of the assassination, and certificate from J. F.[sic] Ford, proprietor of the threatre[sic]. Accompanying this is a copy of this bogus bill which had a wide sale before the fraud was disclosed. This bill contains the following announcement, ‘This evening the performance will be honored by the presence of President Lincoln.’ As it was not known at the time of printing the bills, that Lincoln would attend the threatre[sic], this alone stamps the bill as spurious, but as this fact was not widely known, many of them were disposed of at fancy prices. This bogus bill is seldom met with now, and the three items make a rare and interesting collection in themselves. The latter two are not framed but are in a Booth portfolio.”

Through research, I determined that the J. H. Brown mentioned in the provided provenance was James Hutchinson Brown, a Massachusetts theatrical collector who lived from 1827 to 1897. In 1898, C. F. Libbie and Co. sold off Brown’s extensive collection of dramatic books, autographs, and playbills over the course of three different auctions. The third and final of these auctions occurred on June 15 and 16, 1898. This auction contained a collection of around 180,000 American and English playbills, “formed by the late James H. Brown, Esq., of Malden, Mass.” A digitized version of this auction catalog, housed on the Internet Archive, can be viewed here: https://archive.org/details/cu31924031351533. In examining this catalog, we find the following lot description:

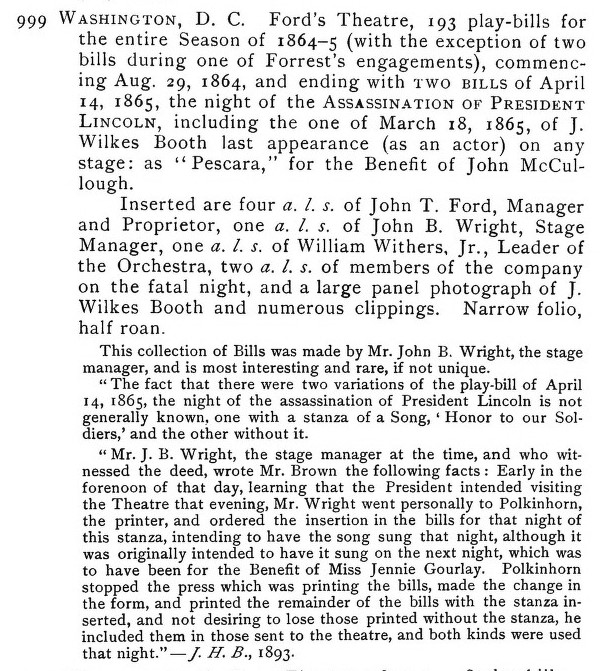

“999 Washington, D. C. Ford’s Theatre, 193 play-bills for the entire Season of 1864-5 (with the exception of two bills during one of Forrest’s engagements), commencing Aug. 29, 1864, and ending with TWO BILLS of April 14, 1865, the night of the ASSASSINATION OF PRESIDENT LINCOLN, including the one of March 18, 1865, of J. Wilkes Booth last appearance (as an actor) on any stage: as ‘Pescara,’ for the Benefit of John McCullough. Inserted are four a.l.s. of John T Ford, Manager and Proprietor, one a.l.s. of John B. Wright, Stage Manager, one a.l.s. of William Withers, Jr., Leader of the Orchestra, two a.l.s. of members of the company on the fatal night, and a large panel photograph of J. Wilkes Booth and numerous clippings. Narrow folio, half roan. This collection of Bills was made by Mr. John B. Wright, the stage manager, and is most interesting and rare, if not unique. ‘The fact that there were two variations of the play-bill of April 14, 1865, the night of the assassination of President Lincoln is not generally known, one with a stanza of a Song, ‘Honor to our Soldiers,’ and the other without it. ‘Mr. J. B. Wright, the stage manager at the time, and who witnessed the deed, wrote Mr. Brown the following facts: Early in the forenoon of that day, learning that the President intended visiting the Theatre that evening, Mr. Wright went personally to Polkinhorn, the printer, and ordered the insertion in the bills for that night of this stanza, intending to have the song sung that night, although it was originally intended to have it sung on the next night, which was to have been the Benefit of Miss Jennie Gourlay. Polkinhorn stopped the press which was printing bills, made the change in the form, and printed the remainder of the bills with the stanza inserted, and not desiring to lose those printed without the stanza, he included them in those he sent to the theatre, and both kinds were used that night.’ – J.H.B., 1893.”

Interestingly, while the assumption would be that Mr. Lang purchased this lot of Ford’s Theatre playbills at auction in 1898, we know that not to be the case. This lot was purchased by another collector named Evert Jansen Wendell (1830 – 1917). After Wendell’s death, this specific collection of Ford’s Theatre playbills was donated to Harvard University. It was this same collection of playbills that Walter Brenner consulted for his 1937 study. At the time of Brenner’s research, the collection still had the two April 14, 1865 bills mentioned in the Brown auction catalog, making it impossible for Lang to have purchased this lot of 193 playbills.

However, this auction catalog does confirm that James H. Brown had dealings with the estate of John Burroughs Wright, the former stage manager of Ford’s Theatre. Wright was a Massachusetts native who maintained a home in the Boston area even when he was working for John T. Ford in Baltimore and D.C. during the Civil War years. After the shooting of Lincoln, Wright returned to Boston. After several seasons touring with star Edwin Forrest and managing theaters in New York, Wright retired from the theater business in 1880. He died in 1893. His wife Annie, who had been present in the audience on the night Lincoln was assassinated, outlived her husband and eventually died in 1924.

The catalogs for the Brown auctions contain several pieces associated to John B. Wright, showing that Brown’s purchases from the Wright estate were more than just the collection of Ford’s Theatre playbills from 1864 – 1865, which eventually went to Evert Wendell. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that John B. Wright possessed more than one copy of the first issue playbill used on the night of Lincoln’s assassination and that James H. Brown purchased it along with the rest of the materials he acquired from the Wright estate. From there, this specific bill was purchased by Frederick Lang, a collector not of theater memorabilia but of Lincolniana.

The framed note, along with the Frederick Lang auction catalog, conclusively traces this playbill back to Ford’s Theatre stage manager John B. Wright. Two other genuine playbills from the Wright collection exist in the Harvard Theatre Collection, demonstrating that Wright retained genuine playbills after the assassination of Lincoln.

In my opinion, the provenance associated with the Doe playbill is strong.

Conclusions: The Doe playbill has all the marks of a first-issue Ford’s Theatre playbill from the night of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. By looking at the minute details, it can be seen that the bill is not a period reproduction, nor is there any evidence of modern duplication. The provenance demonstrates an unbroken line of ownership from John B. Wright, stage manager of Ford’s Theatre, to the current owners, John and Jane Doe. The claims of provenance can be backed up with supplementary evidence in prior auction catalogs.

It is my opinion that the Doe playbill is a genuine playbill from the night of April 14, 1865. As such, it is a rare and unique piece of American history.

Dave Taylor

List of sources and references used in this research:

- Bogar, Thomas A. Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination: The Untold Story of the Actors and Stagehands at Ford’s Theatre. Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 2013.

- Brenner, Walter C. The Ford Theatre Lincoln Assassination Playbills: A Study. Philadelphia: Privately Printed, 1937.

- Brenner, Walter C. Supplement for insertion in The Ford Theatre Lincoln Assassination Playbills: A Study. Philadelphia: Privately Printed, 1940.

- Catalogue of a Lincoln collection formed by Frederick S. Lang, Boston. Boston: C. F. Libbie & Co., 1919.

- Catalogue of the valuable collection of play-bills, portraits, photographs, engravings, etc., etc., formed by the late James H. Brown, Esq., of Malden, Mass. Boston: C. F. Libbie & Co, 1898.

- The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

- Harvard Theatre Collection

- Emails with Jane Doe

I hope you enjoyed a dive into the research and provenance behind the Ford’s Theatre playbill that will be sold by R.R. Auctions. If you’ve always wanted to own one of the rarest pieces of assassination history, you might want to keep on eye on Saturday’s auction. But be prepared to shell out quite a nest egg to add this to your collection. At the time of this writing, during the pre-auction bidding period, this playbill is already up to $55,000 and will likely go much higher before the gavel falls.

Even if you’re like me and will never have the scratch to own something like this, I hope you still enjoyed learning about the playbill and its history. And, if anyone else has any cool priceless artifacts you’d like me to look at, I’m happy to give my opinion. This genuine playbill just goes to show that there are still treasures to be found out there.

Recent Comments