“More is probably known about the people who were at work in Ford’s Theatre on the night of April 14, 1865, and about the topography of the theatre itself than of any other house in the world. We know the names, habits, and duties of every actor, stagehand, ticket-taker, box-office man, and usher*, and we know who many of the audience were.”

This quote comes from the doctoral dissertation of John Ford Sollers, the grandson of Ford’s Theatre owner, John T. Ford. While Sollers’ claim wasn’t quite true when he wrote it in 1962, thanks to modern scholarship, we now really do know a lot about the actors and stagehands of Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. However, despite the wealth of information historians have discovered, we still have one blind spot in our knowledge of the inner workings of the theater that night. This blind spot was even acknowledged by Sollers in his day, forcing him to add a footnote after the word “usher” in the quote above. The footnote attached to it admitted that:

“Unless further information has been found, we do not know the names or even the number of the orchestra”

Music was a crucial part of the theater experience in the Civil War era. Even during non-musical performances (like the comedic play Our American Cousin), an overture and entr’acte music were expected by audiences. Theaters were houses of entertainment, and an orchestra was part of what you paid for when you bought your ticket. We know that Ford’s Theatre had an orchestra. We know that President Lincoln’s party, arriving late to the theater, was greeted by that orchestra. But how much do we really know about the musicians who played that fateful night?

The big challenge when it comes to determining the identities of the orchestra members at Ford’s Theatre is that we lack any sort of list from the period. When John Ford Sollers was writing his dissertation about his grandfather, he had access to documents that had belonged to John T. Ford, and even he could not come up with the names of any members of the orchestra aside from its director. Over the past week, with the assistance of fellow researcher Rich Smyth, I have assembled a partial list of those who were said to have been in the orchestra the night Lincoln was killed. The evidence supporting their attendance is, overall, extremely weak and varies greatly from man to man. Every name must be taken with a grain of salt, and aside from William Withers, we cannot guarantee that any of these men were actually present. With that being said, what follows is the list of the possible Ford’s Theatre orchestra members on April 14, 1865:

William Withers – orchestra director

George M. Arth – double bass

Scipione Grillo – baritone horn

Louis Weber – bass

William Musgrif – cello

Christopher Arth, Sr. – violin

Henry Donch – clarinet

Reuben Withers – drums

Henry Steckelberg – cello

Isaac S. Bradley – violin

Salvadore Petrola – cornet

Joseph A. Arth – drums

Paul S. Schnieder – possibly violin or trumpet

Samuel Crossley – violin

Luke Hubbard – triangle and bells

Below you will find little biographies of each man and the evidence we have about their presence at Ford’s Theatre. I’ve placed them in an order that arranges them from more likely to have been at Ford’s to less likely to have been at Ford’s. Judge the evidence for yourself as we explore the boys in the band.

William “Billy” Withers, Jr. – orchestra director

In 1862, when John T. Ford first remodeled the Tenth Street Baptist Church and opened it up as Ford’s Atheneum, he hired a musician named Eugene Fenelon to be his orchestra director. As director, Fenelon not only conducted the orchestra on a nightly basis, but was also tasked with the duty of recruiting and hiring musicians to ensure that Ford would have an ample-sized band each night. In this capacity, Fenelon recruited local D.C. musicians. Fenelon remained as Ford’s orchestra director until a fire struck Ford’s Atheneum in December of 1862. The loss was a hefty one for John Ford at about $20,000. Consumed in the fire was a bulk of the orchestra’s instruments and music. While Fenelon stayed in D.C. during the process of rebuilding that followed, when the new theatrical season opened in the fall of 1863, Fenelon took a job as the orchestra leader of the recently opened New York Theatre in NYC. Ford was then tasked with finding a new orchestra leader for his new theater. He chose to put his faith in a 27-year-old violinist and Union veteran, William “Billy” Withers, Jr.

Withers was from a musical family, and at the beginning of the war, he, his father, and his brothers had joined the Union army and served as members of a regimental band. The bands provided music during marching and aided with the morale of the men. In the late summer of 1862, however, Congress passed a law abolishing regimental bands, feeling that the service had been abused by non-musical men trying to avoid regular duty and that the bands were not worth the cost during wartime. Though Withers stayed on for some time after the dissolution of his band and acted as a medic, he was eventually discharged. Withers excitedly took up John T. Ford’s offer to be his new band leader. When the new Ford’s Theatre opened in August of 1863, Withers’ orchestra and his experience playing patriotic music were complemented.

“The music under the leadership of Prof. Wm. Withers was highly pleasing, and the execution of the national airs gave a spice to the entertainment, which was fully appreciated.”

Ford’s Theatre had always had a healthy competition with its Washington rival, Leonard Grover’s National Theatre. As the two leading theaters in the city, the press abounded in making comparisons between the two houses. One way the theaters rivaled each other was with their orchestras. While a normal theater orchestra at the time would contain about ten musicians on a nightly basis, both Ford’s and Grover’s began advertising that their orchestras had been “augmented” to include more musicians. It appears that Withers continued to augment the orchestra during his tenure and found his growing of the band to be a point of pride. “Our orchestra under the Brilliant Leader Prof. William Withers, Jr., is considered second to no theatre South of New York,” proclaimed one Ford’s Theatre advertisement. Another highlighted the fact that the orchestra, “has lately been increased and numbers now nearly a Quarter of a Hundred first class Instruments,” and that it had been, “lately largely augmented and is now unsurpassed in numerical and artistic strength.” Billy Withers was a great asset to Ford during his first theatrical season. In addition to his duties as conductor of the orchestra, Withers would occasionally volunteer his services as a solo violinist for special occasions.

Theatrical seasons ended during the hot months, which left many musicians without jobs during the summer. Without the steady (albeit small) income from the theaters, musicians had to make their own arrangements. During this time, many teamed up with other musicians to play small concerts in music halls. With his connections, Withers was able to rent out bigger venues. During the summer of 1864, Withers and his orchestra played concerts at both Grover’s and Ford’s theaters. On July 10, 1864, Withers presented a “Concert of Sacred Music” at Ford’s, for which he brought in two vocalists and “forty musicians of the best talent in the city, forming an array of talent such as has never before appeared jointly in Washington.” The concert was well received, and the proceeds helped the D.C. music scene make it through the lean summer.

When the 1864-65 theatrical season opened in the fall, Withers was rehired by Ford to be his orchestra director. The season started without a hitch, but in January of 1865, Withers experienced some unaccustomed criticism of his orchestra in the press. In comparing the two main D.C. theaters, a reviewer from the National Intelligencer stated that, “In some respects, Mr. Ford has done better. His theater has been uniformly dignified, and he has succeeded in procuring a different class of stars from those played by his competitor…but his stock company has not by any means been all that it should be, and his orchestra needs improvement.” It appears that, perhaps due to this critique, Withers began the process of augmenting the Ford’s Theatre orchestra again. His attention on the theater orchestra was a bit distracted, however, as Withers was chosen to provide some of the music for President Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration ball. He entered into a contract in which he would be paid $1,000 for forty pieces of music. Withers not only used the local talent at his disposal but also brought in musicians from New York. After the inauguration was over, it’s likely that a few of these musicians from New York were hired by Withers to augment the Ford’s Theatre band.

As much as John T. Ford liked being the best, he and Leonard Grover had realized the costly arms race that dueling orchestras would cause them. It appears that sometime over the last two years, the two theater owners had come to a mutual understanding regarding the size of their orchestras. Rather than continuing to attempt to one-up each other, they had put an unknown limit on each other in order to keep the houses equal. When Withers began increasing the size of the orchestra in early 1865, Ford objected, fearing it would break the truce with Grover. On April 2, 1865, Ford wrote a letter to his stage manager, John B. Wright:

“Respecting the orchestra I have promised and wish to keep my word to make my orchestra the same number that Grover has in his – will you notify Withers that for the rest of the season, I wish it reduced. The necessity of this I will explain and stisfy you – If Grover wants Withers – he can go – O can easily supply his place. Let us have the same Instruments that Grover has – my honor is pledged to this.”

Rather than run off to Grover’s National Theatre, as Ford thought might occur, William Withers stayed at Ford’s Theatre and likely reduced his orchestra as ordered.

In addition to being a band leader and talented violinist, Withers also composed music. He wrote several polkas and instrumental pieces, which were sold by local music shops. Another piece that he composed that he had not published was a song called “Honor to Our Soldiers”.

With the Civil War coming to an end in April of 1865, Withers was looking for a chance to perform his own patriotic air, which featured vocalists. He had arranged for a quartet of vocalists to perform the song on the evening of April 15th. However, during the morning rehearsal for Our American Cousin on April 14th, Withers heard the news that the Lincolns, possibly joined by the Grants, were coming to the show that night. Performing his song in front of the President and General Grant would make for a much better debut, and so he decided to perform the piece that night instead. Not having time to arrange for formal vocalists for that night, Withers was forced to rely on the talent around him. Withers tapped three of his coworkers to sing solos in the song: May Hart, Henry B. Phillips, and George M. Arth. May Hart was a new member of the Ford’s Theatre stock company, having been recently transferred from the Holliday Street Theatre in Baltimore. She was performing the minor role of Georgina that night. H. B. Phillips was the acting manager at Ford’s, and it was his job to improve the quality of the stock actors. Phillips is credited as having written the lyrics for “Honor to Our Soldiers”. George Arth was actually a member of the Ford’s Theatre orchestra, who is discussed later. In addition to these soloists, lead actress Laura Keene said she and other members of her company would be happy to sing along as backup.

As we know, the Lincoln party did not arrive at the theater on time. Knowing they were on their way, Withers was given instructions to play a longer-than-average overture in hopes they would appear. After 15 minutes had elapsed without the Presidential party, the play began without them. When the Lincolns, Major Rathbone, and Clara Harris did make their appearance, the play was halted, and Withers and his orchestra began playing “Hail to the Chief”. This was followed by a rendition of “See, the Conquering Hero Comes” as the Lincolns and their guests took their seats in the Presidential box. With that, the play went on.

Withers was initially promised that the performance of his song would occur during the intermission between the first and second acts. However, when the intermission came, he was told by stage manager John Wright that Laura Keene was not prepared to perform during this break and that the orchestra should play his normal intermission music instead. Though slightly annoyed, Withers was assured the song would be performed during the next act break. When the second act break came, however, Withers was once again informed that Laura Keene was not ready. When the third act began, Withers made his way out of the orchestra pit by means of the passageway that led under the stage. He was miffed that his song had been delayed twice. He made his way up one of the two trapdoors on either side of the stage and went to converse with John Wright backstage. Wright said that Withers should plan to perform the song at the conclusion of the play and that Laura Keene had already sent word to the Presidential party to please remain after the curtain fell. Angry at Wright, Withers spied Ford’s stock actress Jeannie Gourlay also backstage and went over to talk with her. It was while Withers was conversing quietly with Jeannie Gourlay about his troubles that the shot rang out.

What occurred next has been well documented. After shooting the President and slashing away Major Rathbone with his knife, John Wilkes Booth jumped from the Presidential box onto the stage. The only actor on stage at the time, Harry Hawk, turned and ran out of Booth’s path. Upon reaching the backstage, it was William Withers and Jeannie Gourlay who stood in the way of Booth’s exit.

“Let me pass!” Booth yelled as he slashed at Withers with his knife, cutting his coat in two places. Booth pushed past Withers and Gourlay, made his exit out the back door, and escaped on horseback into the Washington streets. Withers’ backstage encounter with Booth became a well-known part of the assassination story, and up until his death in 1916, the orchestra leader never passed up an opportunity to tell his tale. As far as evidence goes, William Withers’ attendance at Ford’s Theatre that night is airtight, and even his slashed coat is on display in the Ford’s Theatre museum.

To read more on William Withers, pick up Tom Bogar’s book, Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination, or check out the following articles by Richard Sloan and Norman Gasbarro.

George M. Arth – double bass

Like William Withers, George Arth came from a musical family. At least two of his brothers and his cousin were active in the D.C. music scene. In August of 1861, George Arth joined the U.S. Marine Band, known as The President’s Own band. Arth could play many instruments, but his role in the Marine Band was that of a bass drummer. With the Marine Band, Arth would perform at important events around Washington, often for the President or other dignitaries. The job wasn’t full-time, however, and many members of the Marine Band had other jobs in the city as music teachers or as theater orchestra members. In 1864, while Laura Keene was renting out and appearing at the Washington Theatre in D.C., she hired George Arth to be her orchestra director for the engagement. The job was temporary, however, and when she left the city, George Arth went back to being just an ordinary orchestra member at Ford’s Theatre.

Arth must have had a good singing voice since, as pointed out earlier, he was one of the Ford’s employees that Withers pegged to help him in the singing of his song, “Honor to Our Soldiers”. While we do not have any record of Arth’s whereabouts during the assassination, we can safely assume he was somewhere on the premises preparing for the song when the shot rang out.

An additional piece of evidence we have that places George Arth at Ford’s that night is a letter he wrote in the days following the assassination. After Lincoln was shot, the theater was shut down and subsequently guarded. Members of the Ford’s Theatre staff were brought in for questions, and some were arrested. On a normal night, it was typical for the musicians to leave their instruments in the theater, especially when they were engaged to play the next day. While Arth likely assumed that the next night’s performance at Ford’s Theatre wasn’t going to occur, in the chaos that ensued after Lincoln was shot he was apparently unable to retrieve his own instrument. Unlike some of the other musicians who may have carried their instruments out of Ford’s with them, Arth played the largest bowed instrument in the orchestra, a double bass. After the government locked down Ford’s and started guarding it, no one was able to take anything out of the premises.

On April 21st, Arth wrote a letter to the general in charge of the guard detail asking for permission to retrieve his trapped instrument.

“Respected Sir,

I beg of you to grant me a permit to enter Fords Theatre & bring from it mu double bass viol & bow belonging to me & used by me as one of the orchestra at said theatre – as it is very necessary to me in my profession & I am suffering for its use.

I am humbly your servant

George M. Arth”

Arth’s request was approved, and he was allowed to retrieve his double bass. Arth remained in D.C. after the war and continued working asa musician. He died in 1886 at the age of 48 from consumption and was buried in Congressional Cemetery.

Scipione Grillo – baritone horn

A native of Italy, Scipione Grillo became a naturalized citizen in 1860. He originally made his home in Brooklyn, New York, where he offered his services as a music teacher. By 1861, however, he had relocated his wife and kids to Washington, and in July, he joined the Marine Band. In addition to being a musician, Grillo was a bit of a businessman. When John T. Ford rebuilt his theater after the 1862 fire, he devoted space on the first floor just south of the theater lobby to the creation of a tavern. As part of his property, Ford could lease it out for a profit and provide an easily accessible place for patrons to get drinks between acts. The tavern space was eventually leased by two Marine Band members, Peter Taltavul and Scipione Grillo, who co-owned the venture. They called their establishment the Star Saloon after the theatrical stars who would patronize it. On the night of Lincoln’s assassination, it was Taltavul’s time on duty, and he acted as barkeep to the thirsty theater-goers. Taltavul has become famous for pouring John Wilkes Booth his last drink before the actor assassinated Lincoln.

Scipione Grillo’s partnership in the Star Saloon is often overlooked because he was spending that night in the orchestra instead of serving Booth. While Grillo was required to attend the trial of the conspirators during the entire month of May in 1865, he was never called to testify about his acquaintanceship with John Wilkes Booth and David Herold. It wasn’t until two years later, at the trial of John Surratt, that Grillo took the stand to state what he knew. During his routine questioning, Grillo was asked whether he saw anyone out on the pavement of Ford’s during the show. He replied:

“No, sir. I was not out of the place myself. I was in the orchestra between the first and second acts; but in the third act we had nothing to do, (being always dismissed after the curtain is down,) and so I went out and went inside of my place.”

Grillo also stated that he was still inside the Star Saloon when the assassination occurred. So, while he did not witness the assassination firsthand, he was among the members of the orchestra that night. Since it was part of the Ford’s Theatre building, the Star Saloon was also closed by the government, which ended Taltavul and Grillo’s business together.

Scipione Grillo appears to fall off the map after his 1867 testimony. I have not been able to find any trace of him after that, but it is possible that he, his wife, and children traveled back to Italy to live.

Louis Weber – bass

Louis Weber was born in Baltimore in 1834, but his family moved to D.C. when he was four years old. He became a member of the U.S. Marine Band and played at the inauguration ceremonies for Presidents Buchanan and Lincoln. He was an active member of the Marine Band for 25 years.

In the same manner as George Arth, the evidence pointing to Weber being a part of the Ford’s Theatre orchestra was the return of his instrument by the government. While Weber’s original request does not seem to have survived, on April 28th, Col Henry Burnett (later one of the prosecutors at the trial of the conspirators) sent a telegram off to the general in charge of the Ford’s Theatre guards ordering him to “send to this office, one bass violin the property of Louis Weber”. This order was fulfilled, and later that same day, Louis Weber signed a receipt for his bass.

Weber lived out the remainder of his life in Washington. He died in 1910 from a stroke and was buried in Congressional Cemetery.

William Musgrif – cello

William Musgrif was born in England in 1812. After immigrating to America, he settled in New York. As a musician, Musgrif was skilled in both the violin and the cello, but seemed to have preferred the cello best. In 1842, Musgrif and his cello became founding members of the newly established New York Philharmonic. As part of the Philharmonic, Musgrif mentored younger players in the cello. By 1860, he, along with his wife and son, had moved to D.C., where he offered his skills as a music teacher. Musgrif was also the conductor for his own group in D.C. called the Mozart Society.

The evidence that William Musgrif also moonlighted as a member of the Ford’s Theatre orchestra comes from yet another letter written in the days after Lincoln’s assassination. William Withers had already written once and received a portion of his instruments that had been left at Ford’s that night, but he had not received all of them. In May of 1865, Withers penned another letter asking for permission to get the “balance of my things,” which included “sleigh bells, triangle, harmonica”. He also requested, “one instrument, violocella, for Mr. Musgrive [sic]”

These items were inspected and then delivered to Withers. On May 7th, Withers signed a form stating he had received, “a lot of sleigh bells, a triangle, harmonica, and violincella being properties left at Fords Theatre on the night of the Assassination of President Lincoln.” Withers signed for both himself “and Mr. Musgive [sic]”.

William Musgrif continued to live in D.C. in the few years following the assassination. In 1868, an unfortunate incident caused Musgrif to make the acquaintance of another person who had been at Ford’s on April 14th. On February 19th, Musgrif was in the billiard room of the National Hotel observing a man named William Rogers, who was drunk. When Musgrif attempted to take the billiard balls away from the drunkard, Rogers “hit him over one of the eyes.” A police officer was summoned, arrested Rogers, and proceeded to take down the 56-year-old musician’s sworn statement. That responding police officer was none other than Officer John F. Parker, the man history has condemned for allegedly leaving Abraham Lincoln unguarded on the night of his assassination.

By the mid-1870s, William Musgrif had moved out to Colorado with his son. It is likely he died and was buried there.

Christopher Arth, Sr. – violin

Chris Arth was the cousin of George M. Arth, the would-be soloist for “Honor to Our Soldiers”. His 1901 obituary, which is also one of the pieces of evidence for his presence at Ford’s Theatre, gives a good description of his life.

In addition to this obituary’s claim that Chris Arth was a member of the Ford’s Theatre orchestra, there is also a 1925 article from a D.C. correspondent known as the Rambler that supports the idea. I’ve briefly touched on the Rambler before. His real name was John Harry Shannon, and he wrote for the Evening Star newspaper from 1912 to 1927. His stories involved local interest pieces and often involved him travelling around Washington, talking to old timers. In an article he wrote about the history of D.C.’s music scene, the Rambler included a letter that was written to him by John Birdsell, the secretary of the Musicians’ Protective Union. You’ll notice that in the obituary above, it states that Chris Arth was a member of the same union during his lifetime. Birdsell compliments the Rambler’s work and then poses a challenge to him:

“In this connection it may be possible that, during the course of your researches for the preparation of these writings, you may acquire a complete roster of the orchestra which played at Ford’s Theater the night President Lincoln was shot. I have had inquiry for this from several sources. The first came from somewhere in California. I communicated with the Oldroyd Museum, and while they did not possess this information, they expressed a desire to acquire it.”

After this, Birdsell proceeds to give the list of names he has been able to determine.

“To date the partial roster, which I have is as follows: Leader, William Withers; violin, Chris Arth, sr.; bass, George Arth; clarinet, Henry Donch; cornet, Salvatore Petrola.”

After this list, Birdsell makes the final statement that since average orchestras at the time consisted of 10 instruments, he believes he is only half complete. Birdsell was likely unaware of Ford’s and Grover’s mutually agreed-upon augmented orchestras, which were no doubt larger than ten musicians.

If we trust his obituary and Birdsell’s list, then Chris Arth, cousin of George Arth, was in the orchestra at Lincoln’s assassination.

Henry Donch – clarinet

Henry Donch was a native of Germany who moved to the United States in 1854. He lived in Baltimore and was also a member of the Annapolis Naval Academy Band before he moved to Washington. Donch joined the U.S. Marine Band in August of 1864.

The evidence for Donch’s presence at Ford’s Theatre the night Lincoln was shot is the same as Chris Arth’s: the Birdsell list and his obituary.

A second obituary for Donch provided an additional detail regarding his alleged presence at Ford’s:

“Mr. Donch was a member of the orchestra at Ford’s Theater on the night Lincoln was shot. Mr. Donch, who was facing the assassin as he leaped from the box, always declared that Booth never uttered the phrase, ‘Sic Semper Tyrannis,’ which is attributed to him.”

While the general consensus is that Booth did, in fact, utter the phrase “Sic Semper Tyrannis” after shooting the President, Donch’s contrary claim does not, by itself, prove him to be a liar. The eyewitness accounts from Ford’s vary widely, and it’s possible that, in the confusion, Donch truly did not hear or remember Booth stating these words.

Coincidentally, Henry Donch would observe another Presidential assassin, though this time during the period after his crime. After Charles Guiteau shot President James Garfield, Henry Donch was selected as one of the grand jury members in his trial.

Reuben Withers – drums

Reuben Withers was the younger brother of Ford’s Theatre orchestra director, William Withers. Reuben had joined the same regimental band as his brothers and father at the start of the Civil War, but similarly was sent back home when such bands were disbanded. He joined the ranks of his brother’s brass band and, it appears, the Ford’s Theatre orchestra.

In his older years, William Withers suffered from paralysis and was cared for by Reuben. The two elderly men shared a home and business together in the Bronx. Even in his paralysis, reporters came to hear the story of William Withers being stabbed by Booth on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. In at least one interview, Reuben recounted his own remembrances of the night of April 14th:

“The President was a little late coming in. We had played the overture and the curtain was just going up when we saw him enter the stage box. Brother William immediately started us playing ‘Hail to the Cheif,’ then ‘Star-Spangled Banner,’ and there was a lot of cheering. Everybody was feeling good and happy…

After we had played the overture I left the theatre to catch the 9.20 train for Zanesville, O., and so I missed the actual scene of the great tragedy. I had been offered a better position to play in the band of Bailey’s circus, and I had fixed that night of April 14, 1865, as the time of my leaving Washington…”

Was Reuben Withers truly in the orchestra that night? After years of hearing his brother tell his tale, perhaps he just wanted to include himself in the narrative. Or perhaps he did tell the truth and left the theater before the crime occurred. We may never really know. Reuben Withers preceded his brother in death, dying in 1913. The house and business the Withers brothers owned still stands, albeit a bit modified, at 4433 White Plains Road in the Bronx.

Henry Steckelberg – cello

Henry Steckelberg was born in 1834 in Germany. He immigrated to the United States in 1858, residing at first in New York. When the Civil War broke out, he, like the Witherses, joined a regimental band in New York. After returning to civilian life, Steckelberg made his way to Washington and can be found in the 1864 D.C. directory listed as “musician”.

When Steckelberg died in 1917, his obituary stated that, “On the night of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination he was playing at Ford’s Theater. The orchestra was having an intermission when the tragedy occurred.”

An additional piece of evidence comes from the Steckelberg family. The genesis for this entire post was an email from Steckelberg’s great-granddaughter asking if a list of the orchestra members existed. She told me about her family’s belief that her great-grandfather played that night and that the family still owns Steckelberg’s treasured cello that he, presumably, used. In addition, she was kind enough to send along a letter, written by Henry Steckelberg’s sister-in-law, which supplemented his obituary. The relevant part of the letter states:

“On the night of Lincoln’s assassination, he [Steckelberg] was playing in the regular orchestra in Ford’s Theater. The assassin was a regular hanger on around the theater and he (Booth) often played cards with the orchestra members in the rehearsal room below the orchestra pit. His presence in the theater caused no notice. Booth was unemployed at the time, very jealous of his successful brother. He had no personal animosity toward Lincoln but wished to do something to draw attention to himself.”

It’s hard to tell if the writer of this letter was using knowledge she had obtained from Steckelberg or merely adding her own embellishments and beliefs about the Lincoln assassination story to the basic Steckelberg obituary. The latter part of the paragraph is entirely opinion, and the former contains one factual error: there was no rehearsal room “below the orchestra pit” at Ford’s Theatre, as the pit was the lowest you could get.

While there isn’t much to go on regarding Henry Steckelberg, his obituary does recount that the orchestra was on break during (and therefore didn’t witness) Lincoln’s assassination, which is in line with what Scipione Grillo testified to in 1867. It’s possible that Henry Steckelberg was there after all.

Isaac S. Bradley – violin

Isaac S. Bradley was born in 1840 in New York. During the Civil War, Bradley joined the Union army, where he served as a bugler in the 10th New York Cavalry. Bradley was discharged from the service on November 20, 1865. By 1868, he had moved to Dayton, Ohio, where he married and started a family. He lived in Dayton for the remainder of his days, becoming a photographer. Bradley died on July 10, 1904.

While I have yet to find any period documentation of Bradley’s presence at Ford’s Theatre during his lifetime, in 1960, his elderly daughter Clara Forster was interviewed by a newspaper in her home of Anderson, Indiana. She stated that during her father’s military service, he “fell victim to a rheumatic ailment that hospitalized him for some time in Washington,” and that he, “was ready to accept the offer to play in the orchestra at Ford’s Theater in Washington because he had with him his own Amati violin…”

With her father’s antique violin in her hand, Mrs. Forster then recounted the story her father had told her of that night:

“We were playing very softly when suddenly a messenger came and told us to play louder. We had heard a shot and someone running across the stage above, but we thought nothing of it.

So we played louder, not knowing of the tragedy that had occurred overhead; not knowing that our beloved Abe Lincoln had been shot.”

The article went on to state that “the order to play more loudly was given in an effort to offset commotion caused by the shooting and to avert panic in the audience.” It’s important to note that Mrs. Forster’s account is in contradiction to the testimony of Scipione Grillo, who made it clear that the orchestra was not on duty during the assassination.

Mrs. Forster was very proud of her father’s heirloom violin and described it in detail:

“Mr. Bradley was second violinist in the orchestra, playing with four other young soldiers who had served in the Civil War…

[The violin] had been given to him when he was about 10 or 11 years old. It had been acquired by his grandfather from the Cremonesis family in Italy, reported to have taught the famed Antonius Stradivarius the art of producing priceless violins.

Mr. Bradley was told that the instrument purchased by his grandfather, who served in the Revolutionary War, was made in 1637. A certificate inside the violin bears that date and the name of the maker.

Mrs. Forster reports that her brother, the late Frank Bradley, had the violin in his possession for some time and about 1914 refused an offer of $20,000 for it. During the past few years, Mrs. Forster made her home in Milwaukee, where a concert violinist and teacher became interested in the Amati violin and wrote an article about it for a national music publication. One of the amazing facts was that its owner had carried it with him through much of the Civil War and that it had not been damaged.”

Mrs. Forster appears to be the only source that her father was in Washington and a member of the Ford’s Theatre orchestra that night. She was apparently quite convincing, though, especially with her father’s violin as a witness. In the 1960s, when the National Park Service was preparing a historic structures report about Ford’s Theatre, Mrs. Forster wrote a letter to George Olszewski, the National Capital Region’s chief historian. Olszewski was convinced enough by Mrs. Forster’s letter that he included Isaac S. Bradley’s name in his partial list of orchestra members.

Salvadore Petrola – cornet

Salvadore Petrola, a native of Italy, came to the United States in 1855 when he was 20 years old. A talented cornet player, Petrola joined the U.S. Marine Band in September of 1861 and remained a member for the maximum time allowed, 30 years. As a band member in the 1880s, Petrola was the assistant conductor of the band, second only to its leader, John Philip Sousa. Petrola assisted Sousa in arranging music for the band and served as its primary cornet soloist for many years.

Despite a lengthy search, the only concrete evidence that I have been able to find to support the idea that Petrola was in the orchestra at Ford’s is the list of names John Birdsell, the secretary of the Musicians’ Protective Union, provided to the Rambler in 1925.

One additional fact could be taken as, perhaps, circumstantial evidence in favor of Petrola’s presence, however. The only instrumental solos contained on William Withers’ handwritten copy of his song, “Honor to Our Soldiers”, is for a cornet. In fact, the cornet gets three solos over the course of the song.

Is it possible that William Withers wrote so many solos for his cornet player because he was working with the very talented, Salvadore Petrola? We’ll never know.

Joseph A. Arth – drums

Joseph Arth was the younger brother of Ford’s double bass player, George M. Arth. Like his brother and cousin, Chris Arth, Joseph was a member of the U.S. Marine Band. Like Salvadore Petrola, Joseph stayed in the Marine Band for 30 years.

Our only evidence for Joseph Arth’s presence at Ford’s Theatre comes from his wife’s obituary from 1940. Joseph married Henrietta Scala, the daughter of the one-time Marine Band leader, Francis Scala. Upon Henrietta’s death at 90 years of age, the newspapers highlighted that she was both the daughter and wife of noted Marine Band musicians. In referencing her husband, the obituary stated:

“She was the widow of Joseph A. Arth, drummer with the band during the same period. Files of The [Evening] Star report that Joseph Arth was the drummer in the pit at Ford’s Theater the night President Lincoln was assassinated.”

It’s not much to go on, but perhaps Joseph was playing alongside his older brother George in the Ford’s Theatre orchestra that fateful night.

A pair of drumsticks in the Ford’s Theatre collection. These are said to have been present on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. Could they have been used by Reuben Withers or Joseph Arth?

Paul S. Schneider – possibly violin or trumpet

Paul Schneider was born in Germany in 1844 and immigrated to the United States in 1861. During the Civil War, he joined the Union army under the alias Ernst Gravenhorst. He served as a bugler for the 5th U.S. Artillery from January 1863 until December 1865. In the 1870s, Schneider moved to Memphis, Tennessee, initially working as a musician in the New Memphis Theatre before becoming a music teacher. In 1882/3, Schneider became the second director of the Christian Brothers Band, the oldest high school band still in existence. As director of the band, Schneider and his students performed at important events, including playing for President Grover Cleveland in 1887 when he visited Tennessee. In 1892, Schneider was succeeded as director by one of his former students, but remained in Memphis and was involved in the musical life of the city. He died in 1912.

I have been unable to determine the source of the claim that Paul Schneider was a part of the Ford’s Theatre orchestra on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. It appears to have come after his lifetime but is not well-documented. In 2011, Patrick Bolton, the current leader of the Christian Brothers Band, published his doctoral thesis about the history of the band. The dissertation contains a large amount of information about each band leader and the growth of the band over time. While it gives a great biography of Paul Schneider, the information about his connection to Ford’s Theatre is limited:

“Schneider was also known for his skills as a violinist and performed in touring orchestras around the country, including one that performed in Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. On the evening of April 14, 1865 he has been placed in this historic theatre performing Hail to the Chief for President Abraham Lincoln before the fateful performance of the play, ‘Our American Cousin.'”

Bolton was a good researcher, but it appears that even he had difficulty in finding evidence for this claim. His phrasing of “he has been placed” demonstrates a degree of uncertainty. Likewise, the best reference Bolton could find to support this idea was from a 1993 newspaper article about the Christian Brothers Band, which merely mentioned that Schneider had been a member of the Ford’s Theatre orchestra without any supporting evidence.

Without additional period evidence, I have some serious doubts that Paul Schneider was present at Ford’s. However, the idea that one of their band leaders was a part of such a historic event is a point of pride to the Christian Brothers Band. When the band traveled to Washington, D.C. in 2014, they even presented a picture of Professor Schneider to Ford’s Theatre.

Update: Patrick Bolton has continued his research into Paul Schneider and, in 2025, shared the following obituary for Schneider, which mentions his supposed presence at Ford’s Theatre:

Of course, the idea that Paul Schneider narrowly escaped a bullet from John Wilkes Booth’s gun does not fit the known facts of the assassination. Booth only shot one bullet that evening, and that was nearly point-blank at President Lincoln.

Samuel Crossley – violin

Unfortunately, despite my best efforts, I have been unable to find any verifiable information about Samuel Crossley aside from the story I am going to recount. In 1991, the National Park Service received a donation to the Ford’s Theatre collection in the form of this violin.

The violin was said to have been played at Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. A label inside the violin identified its previous owner, a Union soldier by the name of Samuel Crossley.

On February 11, 2009, at the grand re-opening ceremony for the newly remodeled Ford’s Theatre museum, noted violinist Joshua Bell played the song, “My Lord, What a Morning” on the Crossley violin. In the audience were President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama. Though I haven’t been able to find a recording of that performance, in videos of the President’s remarks, Bell can be seen in the background holding the Crossley violin.

More information about Samuel Crossley (and the provenance behind his violin) is needed.

Luke Hubbard – triangle and bells

Luke Hubbard was born in 1848 in Onondaga County, New York. In 1863, Hubbard attempted to join the Union army but was rejected on account of being under the age limit (he was only 15 at the time). Not one to be deterred, Hubbard waited a year and then enlisted again, this time claiming he was 18 years old. Records verify that Hubbard served as a private in Company B of the 22nd New York Cavalry from July 1864 until he was discharged from service on October 18, 1865. Years later, Luke Hubbard claimed that an unexpected series of events during his tour of service caused him to not only be present at Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination, but also to be an acting member of the orchestra.

The following comes from two sources: an account that Hubbard gave during his lifetime and his subsequent obituary.

“That fall [1864] I was taken ill with fever and removed to Carver hospital in Washington. After I recovered, instead of being returned to my regiment and probably largely because of my youth as well as being in a weakened state, I was given a position in the Carver hospital band. In the army I had been a bugler. This hospital band furnished the music at Ford’s theater on the memorable night. I was playing the triangles and sat at the end of the orchestra under the box occupied by the presidential party…”

“The actor, John Wilkes Booth, was well known by the president, and when he was not in the piece being presented or when Booth was off the stage for a time, or between acts, he would often call on President Lincoln in his box, when both would witness the performance together, or sit and chat in the most friendly manner, so that he had no trouble gaining access to the box on the night of the conspiracy.”

“Many people have claimed that Booth said this or that when he jumped to the stage from the box, but with thirteen pieces playing at the time. I don’t think he could have been heard had he uttered any remark…

In a moment Mrs. Lincoln appeared at the edge of the box, waved her handkerchief to the leader of the orchestra, who raised his bow, a signal for the music to cease. Mrs. Lincoln was then heard to say, ‘The president has been shot.’

The members of the orchestra meanwhile not understanding the scene before them, saw Booth drag himself across the stage holding in one hand the revolver which had done its fatal work, and in the other grasped a knife for use in case the other weapon failed. As the door at the rear of the stage opened, the orchestra members who sprang to the stage saw two pair of arms sieze [sic] the injured man, the last that was seen of him. When the door was reached it was found to be locked on the outside, and by the time they reached the street through another exit the theater was surrounded by a cordon of soldier, and they were obliged to give their names and business at the theater that night.”

“Mr. Hubbard was the third man to climb over the footlights and rush to the back of the stage, but the door was locked on the outside.”

Ironically, one of the most detailed accounts we have from a person who claimed to have been in the orchestra at Ford’s Theatre is also the least factual and least reliable. Very little of what Hubbard recounted is accurate. The orchestra was not playing when the shot rang out. Booth dropped the derringer pistol he used on Lincoln in the box and therefore did not have it on the stage with him. No one grabbed the injured Booth and pulled him out the rear door of Ford’s. The back door of Ford’s was not found to be locked from the outside after Booth passed through it. And perhaps the most egregious (and somewhat laughable) error of them all: John Wilkes Booth was not a friend of Lincoln’s, nor did he often join the President in his theater box to “chat”.

As entertaining as it is, it’s probably safe to dismiss Hubbard’s account entirely. Still, it’s interesting that the instruments Hubbard claimed to have played that night, the triangle and bells, were two of the instruments William Withers asked permission to retrieve after the assassination.

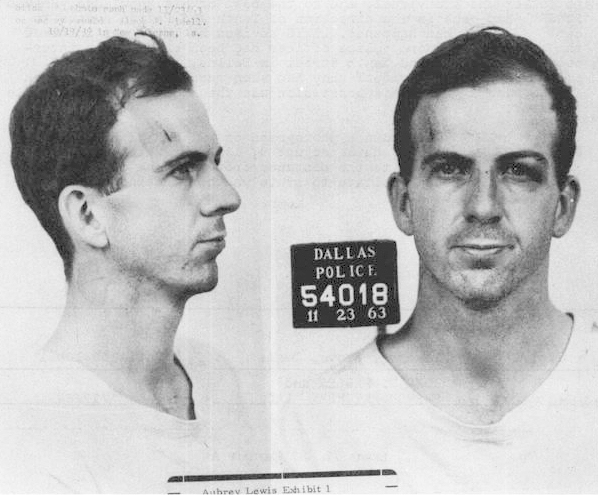

The stage of Ford’s Theatre taken in the days after Lincoln’s assassination. The orchestra pit with music stands and sheet music still in place can be seen at the bottom of the image.

Compared with the stars who graced the stages of Victorian era theaters, the lives of theater orchestra members were without glamour or fame. While equally talented in their own specific roles, many of the men who provided crucial musical accompaniment led quiet and largely uncelebrated lives.

The names listed above are only possible members of the Ford’s Theatre orchestra, with some having much better evidence than others. We only know them because either they chose during their lifetime or their friends and family chose after death, to connect their names with one of the most notable events in our history. This desire to be remembered and connected to such important events leads some people to exaggerate or outright lie. On the reverse, however, it is possible that there were members who did not wish to have their whole musical careers boiled down to a single, traumatic night. How many orchestra members witnessed Lincoln’s assassination, but never talked about it publicly?

As time goes on, additional people who are claimed to have been in the Ford’s Theatre orchestra will no doubt be found. When that happens, we must judge the reliability of their evidence just like the names above. If you stumble across a new name, I encourage you to add a comment to this post so that others may evaluate the evidence.

The exact identities of those playing at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865, will never be known with certainty. Just like in 1925 and 1962, we still do not have a reliable count of how many musicians were even there, and we likely never will.

Known and unknown, the orchestra members of Ford’s Theatre, under the direction of William Withers, have the distinction of having played the last music President Abraham Lincoln ever heard.

References:

The Theatrical Career of John T. Ford by John Ford Sollers (1962)

Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination by Tom Bogar

The Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection

The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence edited by William Edwards and Edward Steers

The Trial of John H. Surratt, Vol 1

Catherine Adams – great-granddaughter of Henry Steckelberg

Restoration of Ford’s Theatre – Historic Structures Report by George J. Olszewski

“The Oldest High School Band in America”: The Christian Brothers Band of Memphis, 1872-1947 by Patrick Joseph Bolton

Rich Smyth

The Art Loux Archive

Newspaper articles discovered via GenealogyBank

Most of the biographical information was compiled through the resources available on Ancestry and Fold3

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Recent Comments