On May 1, 2007, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation, the non-profit fundraising partner of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, purchased a collection of approximately 1,500 artifacts, documents, and photographs from noted Lincoln collector Louise Taper. The collection was purchased by the Foundation for a little over $23 million through the use of a bank loan. The acquisition of the Taper collection was a huge boost for the fledgling state-run library and museum. For while the ALPLM already housed the impressive manuscript collection of the Illinois State Historical Library, the organization at that time lacked a sizable collection of tangible artifacts and relics about the 16th President. The purchase of the Taper collection by the Foundation helped to elevate the collection of the ALPLM, securing its place as a world-class museum. The Taper collection was housed and loaned to the ALPLM until such time as the Foundation paid off the bank loan, and the collection would then be officially donated to the museum and the people of Illinois.

The Taper collection has so many wonderful pieces. This is especially true of its assassination-related items. For while some Lincoln collectors shy away from objects relating to Lincoln’s assassin, Louise Taper collected Booth and Booth family material to the same degree she hunted down Lincoln items. Louise was truly interested in the Booth family and is a coauthor of the edited volume, “Right or Wrong, God Judge Me”: The Writings of John Wilkes Booth. Among the assassination-related treasures in the Taper collection are:

A pair of gloves purported to have been carried by Lincoln in his pockets to Ford’s Theatre on the night of his assassination

One of Lincoln’s cufflinks that he was wearing when he was assassinated (the matching one is in the Library of Congress)

A series of signed letters written by John Wilkes Booth in 1864 to his then-love interest, Isabel Sumner of Massachusetts. Included in the set are photographs (one of which is signed) and the above pearl ring inscribed “J.W.B. to I.S.”

Strands of John Wilkes Booth’s hair encased with his photograph

A rare $30,000 reward poster for Booth, issued by D.C. before the federal reward was created

Also amongst the Taper collection’s papers and manuscripts are countless playbills and likely the largest collection of Booth family letters outside of Edwin Booth’s NYC club, The Players, and the collection of Asia’s letters in the Maryland Historical Society.

Over the years, several pieces in the Taper collection were highlighted in special exhibits in the museum’s Treasures Gallery, which bears the subtitle “Presented by the Louise and Barry Taper Family Foundation”. I was fortunate to see just a bit of the Taper collection when I conducted research at the ALPLM in 2018. The sheer vastness of the collection precluded me from seeing everything I wanted to see, but knowing that it was all in Springfield, just a research appointment away, was reassuring.

However, on October 31, 2022, the loan agreement between the Foundation and the ALPLM ran out. On that day, all 1,500 items in the Taper collection were loaded into boxes and departed. Newspaper articles out of Springfield reported that the items were taken to Hindman Auctions located in Chicago. At this point, the future of the Taper collection is very much unknown, with worries that part, or all, of the collection might be sold. UPDATE: On May 21, 2025, 144 lots of the former Taper Collection will be sold by Freeman’s | Hindman Auctions.

This stunning news begs the question: How did this happen? What caused the ALPLM to lose such a historical gem of a collection?

Well to answer that, we need to understand the history between the Foundation and the ALPLM, how the Foundation came to purchase the Taper collection, how actions over several years caused an irreconcilable rift between the two former partners, and how one specific artifact in the Taper collection, a stovepipe hat said to have belonged to Abraham Lincoln, was weaponized by those in charge of the ALPLM, ultimately leading to the loss of the whole collection.

It’s a complicated and lengthy story. To explain it all, I am relying heavily on a report written in 2019 by Dr. Samuel Wheeler, the Illinois State Historian. Dr. Wheeler was tasked with researching the provenance of the Taper stovepipe hat, as well as the Taper acquisition as a whole. At the end of this post, I will link to Dr. Wheeler’s full, 54-page report, and I highly encourage you to read it for yourself for more details.

For those who don’t have the time to read the full story right now, you can click here to jump down to the tl;dr (Too Long; Didn’t Read) bullet point summary at the end.

The Purchase

Before there was an ALPLM, there was the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation. The Foundation was established in June 2000. Its main task was to fundraise for the creation of the future museum and Presidential library. In 2001, wealthy Lincoln collector Louise Taper became a Foundation board member, using her connections to help solicit donations and advise on possible acquisitions that were coming up at auction. When the ALPLM was opened in 2005, Taper loaned some of her pieces to the museum for their opening exhibits. The centerpiece item from Taper’s collection was a stovepipe hat said to have belonged to Abraham Lincoln.

The hat was touted as one of only three confirmed Lincoln stovepipe hats known, the other two belonging to the Smithsonian and Robert Todd Lincoln’s estate home of Hildene in Vermont. Perhaps no other object personifies the iconic Lincoln than the stovepipe hat. Having a Lincoln hat back in his hometown of Springfield was a celebrated event, even if it was only on temporary loan. Meanwhile, the Foundation continued to be the museum’s main fundraising arm, supplementing the funds provided by the State of Illinois, which owns and operates the site. They also began looking at acquiring more objects and artifacts to strengthen the museum’s physical collection.

A few months after the museum’s opening, Louise Taper informed the Foundation that she was interested in selling her Lincoln collection and that she felt the ALPLM was the perfect place for these items to reside. The Foundation was definitely interested. Acquiring Taper’s items would be a major boost for the museum’s collection. Taper started the process of having her collection cataloged and appraised in order to decide a fair value for the items.

Louise Taper in 2011

It is important to point out that during these initial years, the executive directors of the ALPLM also served as the executive directors of the Foundation. Historian Richard Norton Smith served in both roles until he resigned in March of 2006. His successor, Rick Beard, took over the dual roles in November of that year. Shortly after taking the reins of both organizations, Beard and other board members of the Foundation traveled to Taper’s home in California to view her full collection. During that time, Taper informed the Foundation members that her collection had been appraised at $25 million by appraiser Charles Sachs. She was willing to donate $2 million worth of the collection if the Foundation would purchase the rest for $23 million. Taper also informed the Foundation that another party was interested in the collection and had the funds, so she requested the Foundation work swiftly to determine if they wanted to pursue the purchase.

During the next board meeting, the Foundation decided to form a committee to explore their fundraising capabilities for the future in order to determine whether they could afford to purchase the Taper collection. They promised to get back to Taper about it in early 2007. During the interim, the Foundation requested access to the appraisal Taper had received from Sachs, but Taper stated they would not get access to it until after a purchase agreement was reached. This put the Foundation in an uncomfortable position. They were given the right of first refusal on a world-class collection of Lincolniana, but the clock was ticking, and their ability to be thorough was now severely limited.

Dr. Thomas Schwartz

Dr. Thomas Schwartz had worked for the State since he was hired in 1985 as the Lincoln Curator for the Illinois State Historical Library. He became the Illinois State Historian in 1993 and was the interim director of the ALPLM before Rick Beard was hired. Schwartz had also worked closely with Louise Taper on a number of exhibits. He thoroughly supported the acquisition of the Taper collection, composing a six-page document enlightening the board about some of the artifacts in Taper’s collection. As the State’s lead historian, his opinion carried a lot of weight.

Schwartz suggested the Foundation hire their own appraiser to look at the Taper collection in order to judge the accuracy of Sach’s valuation. This suggestion was agreed to, and the Foundation hired appraiser Seth Kaller for $25,000. Kaller traveled to California and spent several days appraising Taper’s collection. Due to the time constraints in place to reach a possible deal, Kaller was not tasked with delving into the provenance of the pieces in the collection. Dr. Schwartz was content with the provenance of the pieces, and so Kaller was only there to determine the approximate value of the items. In the report Kaller presented to the Foundation board in February of 2007, he wrote, “The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum has indicated that, based on prior in-depth research, it is comfortable with the provenance and descriptions provided. I have therefore made my valuations based on accepting the provenance information provided to me at the start of this project.” In the end, Kaller agreed that $23 million represented a fair value for the items in the collection.

After hearing Kaller’s report, Rick Beard, the director of both the ALPLM and the Foundation, strongly encouraged the Foundation board to support the purchase of the Taper collection. Several board members were concerned about their ability to afford a $23 million debt. Financing options were discussed, and the Foundation acknowledged that purchasing the collection would mean the bulk of their fundraising for the next few years would have to go towards paying down their bank loan. Some board members didn’t like that this would detract from their other activities in support of the museum. In the end, however, the Foundation decided to proceed with the purchase of this once-in-a-lifetime collection.

For the next three months, the Foundation hammered out a purchase agreement and was subsequently given access to Taper’s appraisal from Charles Sachs. That appraisal valued the Lincoln stovepipe hat, the centerpiece of the collection, at $6.5 million, which represented over a quarter of the entire purchase price. At the Foundation’s board meeting of May 1, 2007, they unanimously voted to purchase the Louise Taper Collection of Lincolniana for $23,018,025. Louise Taper, still a board member of the Foundation, recused herself from the vote.

The acquisition was rightfully celebrated as a major achievement, and the Foundation was lauded for its commitment to supporting the ALPLM. Over 1,500 artifacts relating to Lincoln and his life were now destined to become the property of the State of Illinois, once the debt was paid off and the Foundation could legally donate them. Until then, the Taper collection was on loan from the Foundation to the ALPLM with paperwork in place to renew the loan agreement every few years until the debt was paid off. The museum housed the collection, exhibited it, and allowed outside researchers to use it all with the blessing of their partner.

For a brief time, everything was great. The Foundation continued to fundraise, with most of its money now going towards paying down the debt on the Taper collection while still providing some money to the ALPLM for programs and other needs.

Then came the recession of 2008. Both the Foundation and the ALPLM found themselves strained with less money coming in. Since the ALPLM was a government agency funded by the State of Illinois, they felt their belts tighten more as budgets were cut. Then, in October of 2008, Rick Beard was removed as the director of both the ALPLM and the Foundation due to multiple shoplifting arrests. Both organizations were without a permanent director for over two years. While the Foundation continued to work to pay down its debt, the two organizations became aloof as both felt the want of leadership and started griping about money.

A major point of contention came up due to a misunderstanding on the part of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency (IHPA), the then-governing body of the ALPLM. Members of the IHPA board were under the impression that the Taper Collection was to be donated to the ALPLM in pieces. They believed that for each million dollars the Foundation paid off on the debt, a million dollars worth of the collection would be formally donated. The Foundation made it clear that this was an error and that they could not release any of the collection until the full debt was paid, as the bank considered the whole collection as collateral. Despite this explanation, members of the IHPA board publicly expressed frustration with the Foundation, causing more issues between the two partners.

Also during that time, the American Alliance of Museums conducted an assessment of the museum to determine if it was worthy of accreditation. Their report cited several areas that needed improvement. They made the recommendation that the ALPLM and the Foundation should not be directed by the same person. This recommendation was to help prevent possible conflicts of interests between the two separate organizations. During the time when Richard Norton Smith and Rick Beard headed both groups, there was a blurring of responsibilities that the Alliance found fault with. The two organizations should have always been headed by two different directors who worked collaboratively, but separately.

The director of the ALPLM is a political appointment and serves at the will of the Governor. In December 2010, Governor Pat Quinn appointed Eileen Mackevich to be the new director of the ALPLM. Dave Blanchette was the Public Information Officer for the IHPA and deputy director of the ALPLM. In an oral history recording with Blanchette from 2015, he related how, early on, those working for the ALPLM learned that they were in for a rough time with their new director. Mackevich was known to be difficult to work for, taking duties away from managers who had good relationships with lower-level staff in order to freeze them out and consolidate her power. Within a year of her hiring, several members of the staff had resigned, including Dr. Thomas Schwartz, who left to head the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library. Mackevich began having conflicts with the ALPLM’s governing agency, the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Using her own political connections, Mackevich began pushing for legislation to separate the ALPLM from the purview of the IHPA.

In March 2011, the Foundation found its own new director, Dr. Carla Knorowski. While Mackevich’s disputes with the IHPA took a few years to come to a head, there was immediate animosity between the ALPLM and the Foundation after Dr. Knorowski’s hiring. Mackevich and Dr. Knorowski had worked together years before in Chicago. Though details remain vague, their relationship had not been a good one. Despite public claims of trying to bring people together, Mackevich was quickly at odds with Dr. Knorowski in Springfield.

By April 2012, it had been almost five years since the purchase of the Taper collection for $23 million. Even during a tough economic period, the Foundation had managed to lower its debt to $13.5 million. At this point, however, employees suspected Mackevich was working behind the scenes to sabotage the Foundation’s fundraising efforts by encouraging questions about the provenance of the stovepipe hat. According to Dave Blanchette, Mackevich contacted the members of the press to tell them that the hat was possibly not what it seemed.

Before discussing the ensuing newspaper article that lit the fuse, let’s look at the provenance of the stovepipe hat for ourselves, using the research done by Dr. Samuel Wheeler in his 2019 report.

The Provenance

The stovepipe hat in the Taper collection is accompanied by a 1958 affidavit signed by Clara Waller. Mrs. Waller recounted that the hat had belonged to her late husband, Elbert Waller, who had received it from his father, William Waller. According to Clara’s affidavit, William Waller traveled to D.C. and met Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. Discovering they wore the same hat size, the two men exchanged hats. Waller returned home to Illinois and kept Lincoln’s stovepipe hat as a treasured memento until his death in 1891.

In addition to Clara Waller’s signed affidavit, there was also a letter Clara wrote expanding a bit on the story. She stated that William Waller had worked as an agent of sorts during the Civil War, helping to root out anti-Union activities in Illinois. It was due to that course of work that he traveled to D.C. and met Lincoln. During his 2019 research into the hat, Dr. Wheeler could not confirm that William Waller had been employed as either an official spy or civilian informant, but recommended more research into documents held by the National Archives to explore the possibility.

The hat also came with a 1958 letter from John W. Allen, who had served as the curator for the Southern Illinois University museum. Allen wrote that he had heard the same story told by Ms. Waller from her late husband, Elbert, and that he was “inclined to give it full credence.” These notes are the entire provenance behind the hat.

After the death of Elbert Waller in 1956, Clara went through the process of selling his things. He was an antique collector, so Clara had her work cut out for her. Clara took several of her late husband’s pieces to the Tregoning Antique Shop located in Carterville, Illinois. While there, she sold the hat to the owners of the antique store after learning that they were planning on starting a small museum about Southern Illinois. She sold them the hat for $1.

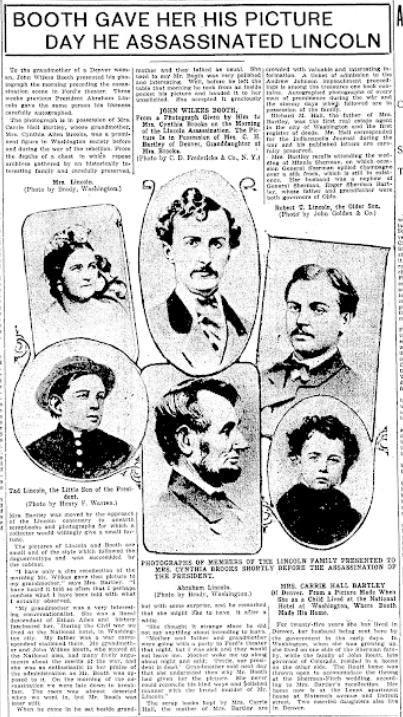

James T. Hickey

The hat stayed at the Tregoning Antique shop until 1958, when it was purchased for an unknown amount by James T. Hickey. Earlier that same year, Hickey had become the first Curator of the Lincoln Collection at the Illinois State Historical Library. The antique store gave Hickey the contact information for Mrs. Waller, and he wrote to her about the hat. He also wrote to John W. Allen at Southern Illinois University. Their responses to Hickey constitute the aforementioned provenance for the hat.

While one might expect that the new Lincoln curator would purchase the stovepipe hat for his library, Hickey actually bought it for his own collection. Hickey had gotten his job due to his expertise as a Lincoln collector, and he remained an active buyer of Lincoln items for decades to come. This, of course, presented a huge conflict of interest with his role as curator of the State’s Lincoln collection and is now considered unethical behavior. Still, nothing was done about this issue at the time.

Hickey was proud of his newly acquired Lincoln stovepipe hat, and it was obviously a treasure in his collection. He loaned the hat out to a traveling exhibition during America’s bicentennial in 1976. In 1981, the hat was used by the Illinois Secretary of State to settle a dispute over new legislative districts. The winner was literally pulled from the stovepipe hat.

In 1988, Hickey allowed the hat to travel internationally as it held a place of prominence in an exhibit in the National Museum of History in Taipei, Taiwan. Hickey was happy to loan out his unique piece of American history so that the masses could see it and be in awe.

During his time as the Lincoln curator, Hickey befriended Louise Taper, who had once worked a part-time job for a rare book dealer in Beverly Hills, where she was paid in books and manuscripts. After acquiring her first Lincoln signature in this way, Taper was hooked. In 1985, Louise married Barry Taper, the son of a wealthy California developer, and her passion for collecting increased tenfold. Taper began buying practically everything she could find relating to Lincoln and often consulted with James Hickey and his expertise about Lincoln artifacts. The two became good friends as a result.

Over the years, several trustees of the Illinois State Library questioned Hickey’s close involvement in the Lincoln trade and disliked the conflicts of interest that existed when he went to acquire things for the library, only for them to go to his own collection instead. Hickey also made money on the side appraising the value of Lincoln collectables, which bothered the trustees. Still, it wasn’t until 1984 that Hickey was required to sign an agreement stating that he would no longer engage in the purchase or appraisal of Lincoln items over $100. Hickey signed the agreement, but then retired as the Lincoln Curator five months later.

James Hickey, Thomas Schwartz, and Barry Taper (husband of Louise Taper) circa 1993

Thomas Schwartz was hired in 1985 as Hickey’s replacement as the Lincoln Curator of the Illinois State Historical Library. He found things at the ISHL in poor shape. The collection was disorganized and without an inventory. Provenance records were vague or incomplete. Even though Hickey had retired, he still returned to the ISHL often to visit with his former co-workers. Hickey befriended Schwartz, and the new curator realized the benefit of Hickey’s almost 30 years of institutional knowledge about the collection. Due to his conversations with Hickey, Schwartz was slowly able to help put the ISHL’s collection in some semblance of order. In this way, Hickey also became a mentor to Schwartz, who was still only a graduate student at that time.

Like his mentor, Schwartz quickly became familiar with Louise Taper. Like Hickey, Schwartz similarly conversed with her about Lincoln artifacts that sprang up for auction, though Schwartz never had his own Lincoln collection and was not allowed to appraise any Lincoln items. Still, the two became close.

Thomas Schwartz (r) with Louise Taper (c) on a visit to Beverly Hills see her Lincoln collection in 1993.

Near the end of his life, James Hickey started to sell off parts of his own Lincoln collection. During his career as the Lincoln Curator, he had befriended Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith, the last confirmed descendant of Abraham Lincoln, and had received several items from him personally. Some of those items went to the ISHL, while others went into Hickey’s collection. He sold some of the items he got from Beckwith, along with other pieces in his collection, to his friend Louise Taper. In 1990, Hickey sold the Lincoln stovepipe hat to Taper for an unknown sum. Hickey died in 1996.

Thomas Schwartz (l) and James Hickey (c) in 1995

How much Louise Taper investigated the provenance of Hickey’s stovepipe hat is unknown. During the 1990s, Taper twice loaned the hat to major exhibitions regarding Abraham Lincoln, working alongside Thomas Schwartz in the process. Dr. Schwartz later stated that he was unaware of the exact provenance of the hat, but knew that it had come from the collection of his former mentor, Hickey. Apparently, Hickey’s belief that the hat belonged to Lincoln was all the assurance Dr. Schwartz needed.

After the Foundation purchased the entire Taper collection in 2007, Dr. Schwartz was involved in the initial packing of Taper’s collection in Beverly Hills. He would later state that it was during that time that he first saw provenance for the hat. He had assumed Hickey had been given the hat by Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith and was surprised to read the Clara Waller statements. Still, it appears that Dr. Schwartz’s trust in his now deceased mentor remained, and he did not raise any alarms to the Foundation as he continued to catalog the vast collection.

A few weeks after the collection arrived at the ALPLM, Dr. James Cornelius, the recently hired Lincoln Curator, appears to have begun the research process on the stovepipe hat. An internal email revealed he emailed the in-house staff of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln Project, asking if they had any information on William Waller. The Papers didn’t have anything in their files regarding Waller, but did provide an 1850 census record containing him and suggested Dr. Cornelius consult some local county histories to look for more.

However, before Dr. Schwartz departed the ALPLM in 2011 to head the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, he and Dr. Cornelius decided to revise the hat’s provenance. On September 15, 1858, opposing candidates for Senate, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas, engaged in the third of their now-famous Lincoln-Douglas debates. This debate occurred in Jonesboro, Illinois, which was located just a few miles from the home of William Waller. Drs. Schwartz and Cornelius posited that it made more sense that the Southern Illinoisan farmer attended this debate and exchanged hats with Lincoln then, not in D.C. during the Civil War.

While their theory of candidate Lincoln giving away a hat in 1858 may be more plausible than President Lincoln trading hats in the midst of the Civil War, no evidence has been found to prove that William Waller even attended the Jonesboro debate. The Jonesboro theory dismisses the little provenance that the hat actually has going for it – Clara Waller’s statements.

Items with shaky, family-statement type provenance exist in every museum’s collection. In the world of Lincoln collecting, it is not unusual to come across many items where the provenance is solely based on family lore. However, it’s hard to find an item with comparable provenance still being valued at $6.5 million. That value, given by Taper’s appraiser, was agreed upon by Seth Kaller in his appraisal for the Foundation based on the understanding that the hat’s provenance was unquestioned. Clearly, however, there is a lot to question about this hat’s provenance.

The Press

ALPLM director Eileen Mackevich knew about the questions regarding the hat’s provenance. In her mind, it was the perfect weapon to use in her feud against her rival, Foundation director Dr. Knorowski. According to David Blanchette, the former Communications Manager for the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency and Deputy Director of the ALPLM, Mackevich fed information to Bruce Rushton at the Illinois Times regarding the questionable provenance of the hat and the conflicting theories about it. Similarly, Blanchette noted that Dave McKinney at the Chicago Sun-Times was also getting information from “a very limited scope of individuals who had very specific knowledge… very, very far inside” the ALPLM. Armed with this insider information, McKinney interviewed Dr. Cornelius and, on April 18, 2012, published the article, “Was famous stovepipe hat really Abe Lincoln’s?”

This article publicly discussed the provenance of the hat for the first time and highlighted the contradictory nature of the Jonesboro theory when compared to Clara Waller’s statement. Dr. Cornelius still supported the Jonesboro theory but did provide some room for retreat:

“In a court of law, there are different levels of assurance,” said James Cornelius, curator of the museum’s Lincoln Collection. “The Scottish legal system has guilty, not guilty and not proven. We elected in this country not to take that third option, in which the presumption of guilt is kind of heavy. I guess, if you want to be pushy about the hat question, you’d have to judge it in the not-proven category of Scottish law because it cannot be proven or disproven.”

Other articles with similar questions about the hat followed. This became a bad time at the ALPLM, with some questioning whether their director was fueling the media’s speculation, while others went into damage control mode to salvage the hat’s provenance. Around this time, a document titled “Lincoln Stovepipe Hat: The Facts” was produced by the ALPLM, which laid out nine claims about the hat. This document was to be used when dealing with press and visitor inquiries about the hat, with staff being told not to deviate from it. The text of the document is as follows. I have numbered the list for ease of discussion:

Lincoln Stovepipe Hat

The Facts

- The hat comes from the Springfield store run by Josiah H. Adams, where Lincoln bought other hats and clothing. A check from Lincoln to Adams still exists.

- The hat is the same size that Abraham Lincoln wore: 7 1/8

- The interior of the hat shows evidence that someone stuck documents in it, as Lincoln frequently did.

- The hat was owned for a century by the Waller family. William Waller was a prominent southern Illinois farmer who left the Democratic Party and became a Lincoln supporter, angering his Democratic neighbors.

- Waller would have attended the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debate in Jonesboro, a town just a few miles away from his home.

- Waller’s son Elbert, a state legislator and author of two books on Illinois history, said his father obtained the hat from Lincoln.

- Elbert Waller’s widow said in a sworn statement in 1958 that her father-in-law had gotten the hat from Lincoln. She said that her husband, when he inherited the hat, considered it a prized possession.

- Southern Illinois historian John Allen said he had discussed the hat with Waller’s son Elbert and gave “full credence” to the hat’s authenticity.

- Noted Lincoln collectors James Hickey and Louise Taper were each confident enough in the hat’s origin to buy it in later years.

In his report, Dr. Wheeler broke down these claims and found several of them to be incorrect. Here is a summary of his findings:

- There is no evidence inside the hat that connects it with hatmaker Josiah Adams or any hatmaker in Springfield, Illinois.

- Dr. Wheeler could find no documentation in the file showing that the hat had been measured. During his own research, Dr. Wheeler and two others each measured the hat. They all came with a measurement of 7 1/4″, not 7 1/8″. This makes the hat a bit larger than the Smithsonian and Hildene Lincoln hats.

- Lincoln was known to keep documents in his stovepipe hat, and in a video recorded for ALPLM about the hat in 2011, Dr. Cornelius similarly claimed that there was evidence that Lincoln stored documents in this hat as well. However, Dr. Wheeler’s examination of the hat found that the silk band on the inside was loose, “but there is no opening in the lining where one might place a document for safekeeping.”

- This claim appears to hold up to the limited biographical material we have on William Waller, mostly written by his son.

- As discussed earlier, there is no confirmation that William Waller attended the Jonesboro debate. (The question that arises in my mind is that, even if Waller did attend the Jonesboro debate, why would the still staunch Democrat and Douglas supporter want anything to do with Lincoln, or his hat?)

- Claims 6 – 9 are essentially correct, though claim 7 leaves out the fact that Clara Waller stated her father-in-law got the hat from Lincoln in D.C.

Dr. Wheeler was surprised at the content of this guiding document, as the first three points were demonstrably untrue. As Dr. Wheeler summed up in his report:

“In response to the provenance issues that were raised in 2012, ALPLM did not respond like a responsible museum. Instead of conducting an honest inquiry and perhaps seizing on the opportunity to educate the public about provenance-related issues, ALPLM assumed an overly defensive position. The 2013 document, “Lincoln Stovepipe Hat: The Facts,” contains untruths and appears to have been issued solely to combat critics.”

In response to the press reports, the Foundation also undertook an investigation into the hat. The hat’s provenance was casting a shadow on the whole collection and its authenticity, impacting their ability to pay off the Taper debt. The Foundation created a special committee to investigate. They started by analyzing the purchase of the Taper collection. The internal committee upheld that they had acted properly in purchasing the collection as they did so on the recommendation of Dr. Thomas Schwartz, the expert most qualified to speak on the collection. In November 2013, the Foundation asked two museum representatives to come and look at the hat and assess its provenance. The individuals were Harry Rubenstein from the Smithsonian and Russell Lewis from the Chicago History Museum. Both men agreed that the existing provenance from Clara Waller was, “insufficient to claim that the hat formerly belonged to President Abraham Lincoln,” and recommended the museum, “take a less defensive position” regarding it. It’s worth noting that Rubenstein and Lewis had experience with Lincoln hats. The Smithsonian has the hat Lincoln wore to Ford’s Theatre, which was collected by the War Department after the crime, while the Chicago History Museum has a hat supposedly given by Lincoln to his footman, Charles Forbes. The provenance behind the Forbes hat is weak, and the Chicago History Museum is upfront about this. The hope was that the ALPLM would be more realistic about the hat going forward, which would lessen the controversy.

But the Foundation was not made up of historians. Just as they relied on Dr. Schwartz when the Taper collection was purchased, they relied on Dr. Cornelius now when it came to researching the provenance. In many ways Dr. Cornelius was an ally for the Foundation while it continued to be at odds with his boss, Director Mackevich. In 2015, the Foundation worked somewhat clandestinely with Dr. Cornelius to have the hat DNA tested. On two separate days in March 2015, agents with the F.B.I. came in and took samples from the hat. This was without the knowledge of anyone at the ALPLM except for Dr. Cornelius. Attempting to find DNA on the hat had actually been suggested by a trustee of the IHPA, the ALPLM’s governing body, back in 2013, but Dr. Cornelius had advised against it, saying it was unlikely any period DNA would be present. It is unknown what caused Dr. Cornelius to change his mind and support the Foundation’s DNA test two years later. Still, his original opinion proved correct. When the FBI gave their report to the Foundation in 2017, the only DNA they found on the hat matched an individual who had recently handled it, likely Dr. Cornelius himself. There is no nineteenth-century DNA left on the hat.

Before the results of the DNA were known, the Foundation’s special committee had determined that they “did not find any additional evidence to strengthen the provenance of the hat” but that they had also not found “any evidence to the contrary” to discredit it as Lincoln’s. They were content with the Waller affidavit (at least part of it) and the expertise of Dr. Cornelius, who continued to support his interpretation of the provenance.

In 2016, the Foundation published a book entitled Under Lincoln’s Hat: 100 Objects that Tell of His Life and Legacy. The book highlighted pieces from the ALPLM’s collection, several of which came from the Taper purchase. The authors of the book were Dr. Cornelius and Dr. Knorowski, the director of the Foundation. Board member Louise Taper wrote the preface. The hat is featured prominently on the cover of the book. The page that specifically discusses the hat shows the conflict and defensiveness that still existed on the part of the Foundation and Dr. Cornelius. While the book recounts the provenance that Lincoln gave the hat to William Waller and that it was passed down in his family, it fails to mention where this occurred. Most frustratingly, the text near the middle of the page states definitively that Lincoln bought the hat, “for about four dollars,” from “a millinery shop owned by Josiah H. Adams”. It appears that the authors have doubled down on claim (1) from the “Lincoln Stovepipe Hat: The Facts” document from 2013, connecting the hat to the Springfield hat maker. Again, however, Dr. Wheeler’s 2019 report states that there is no identifying maker’s mark in the hat aside from an unidentified faded floral motif. In addition, while the 2013 document just noted that, “[a] check from Lincoln to Adams still exists,” the authors of this book imply that documentation of Lincoln purchasing this hat specifically exists, which is untrue.

Another claim that is made in the book, which was verbally repeated by many at the ALPLM, concerns the two marks of wear on the brim of the hat. This was attributed to Lincoln repeatedly taking his hat off in order to politely gesture to passersby. At one point, it was thought that the two finger tip marks could be measured and compared with another person of Lincoln’s height for comparison. However, as Dr. Wheeler notes in his 2019 report, it strains believability that a person would grab the two exact same spots on a hat every time they took it off. Wear on account of repeated doffing of the hat would result in a larger worn area around the same side of the hat, not two distinctive finger holes.

The Politics

Eileen Mackevich resigned as the director of the ALPLM in October 2015. But the damage she had done during her almost five years in the position remained. Questions about the hat had derailed the Foundation’s fundraising efforts. They had to refinance the loan at a higher rate, causing them to owe more money due to increased interest. Also, as has been demonstrated, both the Foundation and the ALPLM took an extremely defensive position on the stovepipe hat, which, based on the provenance they had, was a serious mistake.

Alan Lowe was appointed by the Governor to head the ALPLM in July 2016. He had previously been the founding director of the George W. Bush Presidential Library. Like Mackevich before him, Lowe formed an adversarial relationship with the Foundation. This became especially true in 2018, as the Foundation was lobbying the Illinois General Assembly for an appropriation to help settle the remaining $9 million Taper debt. In January 2018, Lowe first became aware of the clandestine FBI investigation on the part of the Foundation and Dr. Cornelius. He was angry that the Foundation had had the results since 2017 but had not shared them with him. In March of that year, Dr. Cornelius was put on administrative leave from the museum for reasons unrelated to the hat investigation and later resigned from his position. In August 2018, Lowe first became aware of the 2013 investigation by Harry Rubenstein of the Smithsonian and Russell Lewis of the Chicago History Museum when one of the authors emailed it to him. He again was upset with the Foundation’s lack of transparency. It was at this time that Director Lowe tasked Dr. Wheeler with conducting research into the hat and the Taper purchase. However, Lowe did not alert the Foundation about the new research.

On September 19, 2018, reporter Dave McKinney, the same Springfield journalist who had first reported on the hat’s provenance back in 2012 due to a tip from “very, very far inside” the ALPLM, published an article entitled “Report: Existing Evidence ‘Insufficient’ To Prove Hat Belonged To Lincoln”. The article recounted the 2013 findings of Rubenstein and Lewis, along with the failed F.B.I. DNA test. The story was also picked up by the New York Times, which published its own article on the matter a few days later.

Lowe was quoted in the New York Times as feeling duped by the Foundation in regards to the hat:

“I was assured everyone thought it was real,” Mr. Lowe said. “I became that guy, saying, ‘I think that hat is real. I think it’s authentic.’”

In October 2018, Lowe announced to the Associated Press that he had dissolved his $25,000-a-year consultancy contract with the Foundation. The Governor had asked the Foundation to offer the contract to Lowe in 2016 to help supplement his State salary and incentivize Lowe to take the ALPLM director position. In regard to ending the contract, Lowe was quoted as saying, “I don’t want there to be any question about my priorities.”

Under Lowe’s leadership, the relationship between the ALPLM and the Foundation deteriorated rapidly. He had publicly accused the Foundation of lying about the hat, even though his own employee had been a major part of the endorsing and disseminating of unsubstantiated provenance. Lawmakers in Springfield were dismayed that their State institution was being raked through the mud in the pages of the New York Times. In April 2019, Lowe took the next step in attempting to cut out the Foundation. He ordered that all direct communication between ALPLM staff and members of the Foundation was to cease. Instead, all of their communications were to be funneled through the ALPLM Chief of Staff.

Alan Lowe (l) and Dr. Samuel Wheeler (r) in 2018

In May 2019, Dr. Wheeler requested that a textile expert be brought in to consult on the hat. He contacted the Foundation with his request. The Foundation responded with surprise, as they were unaware Director Lowe had ordered new research on the hat. In the same way Lowe had criticized the Foundation for not having been transparent with their investigations of the hat, now the Foundation was upset that they had not been informed of efforts on the ALPLM’s part. The Foundation requested that Lowe meet with them to discuss the investigation taking place so that they could work collaboratively on the project. Lowe never responded to the Foundation’s letter.

A few days after this, the Foundation failed in its lobbying effort to secure funds from the Illinois General Assembly to pay off the remaining Taper loan. Likely due to the recent uproar over the hat’s provenance, the Governor had given his opinion that it was not appropriate to use State funds to settle the non-profit’s debt. The next day, Director Lowe told Dr. Wheeler to stop his research into the hat and Taper collection, citing his frustration with the Foundation for not bringing in a textile expert. However, this was due to Lowe’s own refusal to update the Foundation about the work being done.

With the bank loan due in October, the Foundation was forced to renegotiate with its bank. While the bank had every right to seize the collection due to insufficient payment, no one at the bank wanted the bad press of forcibly repossessing Lincoln treasures from the museum. The Foundation was successful in refinancing their loan agreement and were given more time to pay off the debt, but faced a much higher interest rate going forward.

In June of 2019, Director Lowe sent an email to Deputy Governor Jesse Ruiz stating, “It appears from my discussion with the state historian that he and his team have found no evidence confirming the hat belonged to President Lincoln.” Through a Freedom of Information Act request, this email was received by reporter Dave McKinney. In his report, Dr. Wheeler implies that ALPLM administrators likely tipped off McKinney about the email, leading him to file his FOIA request. One wonders if the FBI and Rubenstein/Lewis reports arrived in media hands through similar channels. In September 2019, McKinney published an article titled “Illinois State Historian Finds ‘No Evidence’ Disputed Hat Belonged To Abraham Lincoln.”

The article recounted the continued sniping between the ALPLM and the Foundation, with the hat controversy at the center. Lowe accused the Foundation of preventing a textile expert from coming in, while the Foundation stated that Lowe refused to meet with them to discuss the research so far, while also cutting them off from ALPLM staff members. Dr. Wheeler disagreed with the conclusion and headline of the article. While he had not found any new evidence so far, the research was still incomplete, having been halted by Director Lowe in response to his feud with the Foundation.

In another unexpected twist, Alan Lowe was fired from the ALPLM on September 20, 2019. Working from an anonymous complaint, the Office of the Executive Inspector General had determined that Lowe had violated museum procedures by loaning out the museum’s copy of the Gettysburg Address written by Lincoln to political personality Glenn Beck. The Gettysburg Address was hastily loaned to a pop-up exhibit Beck put on in Dallas in exchange for Beck helping to fundraise to pay off the Taper debt. Beck’s organization sent Lowe a check for just over $50,000 in exchange for the loan. The Inspector General agreed with the whistleblower’s complaint that Lowe had “pimp[ed] out” the ALPLM’s most precious artifact, which resulted in his removal by the Governor.

Lowe’s firing left the ALPLM without a director. Chief of Staff Melissa Coultas was made Acting Director in the interim. Power was also shared by Toby Trimmer, the ALPLM’s Chief Operating Officer, and the museum’s General Counsel, Dave Kelm. Immediately after taking over, the three administrators ordered Dr. Wheeler to write a report that summarized his findings on the hat. Dr. Wheeler countered that his research was not complete and that he didn’t want his incomplete work used in the media as further evidence against the provenance of the hat. He suggested that he instead make a verbal update at a shared meeting with the ALPLM and Foundation. After making this suggestion, Dr. Wheeler was ordered to a meeting with ALPLM administrators and Deputy Governor Jesse Ruiz. Dr. Wheeler once again suggested a joint meeting between the Deputy Governor, ALPLM officials, and the Foundation to explain his research and collectively come up with a plan. ALPLM administrators disagreed with Dr. Wheeler’s suggestion. In the end, Dr. Wheeler was ordered to have a written report turned in on November 25, 2019. The report would be reviewed by ALPLM administrators Coultas, Kelm, and Timmer, then given to the newly created ALPLM board (the ALPLM was no longer under the purview of the IHPA due to the actions started by Mackevich and completed under Lowe). The ALPLM board would then give the report to the Foundation (cited as the ALPLF in the document). Dr. Wheeler was also informed that he would give a verbal report to all three parties, plus the Deputy Governor, on November 26. I quote now from Dr. Wheeler’s report:

“During the ensuing conference call I learned that no one had received a copy of the report I had submitted to ALPLM administrators the previous day. For the next 40 minutes, I summarized the report, detailing the steps I took during the research, the new information I was able to uncover, and advocated for restarting the research process so I could reach a definitive conclusion and write a report that would put the issue to rest. When discussion turned to whether my report would become a public document, Coultas said ALPLM might redact some of the material I had written, specifically my claim that the hat had been weaponized by ALPLM administrators. I objected to any redactions, especially this one, because it was an essential part of the story. As far as I was concerned, everything that has happened regarding the stovepipe hat since it was acquired in 2007 is part of the hat’s history and helps inform the current troubled relationship between ALPLM and ALPLF.”

At the end of the call, the Foundation suggested that Dr. Wheeler may benefit from consulting their files on the negotiations that took place between the ALPLM, the Foundation, and Louise Taper prior to the purchase. Dr. Wheeler was thus given an extension on the final draft report and given access to these files. He turned in his report on December 16, 2019, which he titled “Status Update: Provenance Research on the Stovepipe Hat (TLR 001)“.

Dr. Wheeler maintains throughout the report that he had made no definitive conclusion about the hat and that more research was necessary. He still wanted to bring in a textile expert to try and date the hat and wished to conduct research at the National Archives to see if he could find William Waller among a list of Union agents or civilian informants, which would give credence to Clara Waller’s statements.

Dr. Wheeler concluded his report with five recommendations:

- First, further research into the stovepipe hat is abundantly warranted, but ALPLM and ALPLF should work collaboratively to outline next steps.

- Second, ALPLM should improve its current acquisition process to ensure adequate research is completed prior to adding an item to its collection or advising ALPLF to acquire an item on its behalf.

- Third, ALPLF should reexamine its conflict of interest policy to ensure it conforms with national standards and engage its board members in regular conversations about the importance of putting the interests of the board ahead of their own.

- Fourth, the weaponization of the stovepipe hat must end immediately, and both the ALPLM and ALPLF must rededicate themselves to working collaboratively.

- Fifth, ALPLM and ALPLF should rededicate themselves to truth, transparency, and strive to achieve “excellence.”

Dr. Wheeler essentially begged the two organizations to set aside past disputes and come together. Both were guilty of acting poorly toward each other over the past few years, but the in-fighting needed to stop if they were to move forward in partnership. In his own way, Dr. Wheeler embodied the appeal Lincoln made in his first inaugural address, stating, “We are not enemies, but friends. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection.”

On January 15, 2020, Dr. Wheeler presented his updated report to the new ALPLM board. For a brief moment, there was hope. The board agreed with Dr. Wheeler’s recommendations and decided to appoint a joint committee with members of the ALPLM and Foundation board to come together to form a plan. The COVID-19 pandemic slowed down the formation of the joint committee, but on July 7, 2020, the joint committee of the ALPLM and Foundation board members was held. Dr. Wheeler presented an oral report to that joint committee. The joint committee agreed with Dr. Wheeler’s recommendation to bring in a textile expert, and the two groups agreed to split the cost evenly. The next ALPLM board meeting reported favorably on the committee hearing. Finally, the two partners were working together in a common cause. However, this instance of cooperation didn’t last.

Less than ten days later, on July 15, 2020, Dr. Samuel Wheeler was removed from his position as the Illinois State Historian. Since he served at the will of the Governor, no reason was given for his removal. However, it seems clear that his criticism of ALPLM leadership and his refusal to let his research be used as a weapon in a war between the ALPLM and its partner Foundation led to his removal.

The Predictable

The day after his removal, ALPLM administrators Coultas, Trimmer, and Kelm seized Dr. Wheeler’s stovepipe hat research material. The ALPLM/Foundation joint committee that had agreed to work together and approved bringing in a textile expert never followed through, and no further updates were given. The brief period of cooperation was gone, and the ALPLM continued their war against the Foundation. They accused the Foundation of not being fiscally transparent and felt that the Foundation was not giving enough money to the ALPLM. The Foundation responded that they had given the museum almost $42 million since the ALPLM opened, including acting as vendor for their gift shop and restaurant, and providing the grant funding for the Papers of Abraham Lincoln Project. In short, the Foundation took offense at being accused of not providing for their partner museum. The ALPLM leaders claimed it wasn’t enough and that all of the money raised by the Foundation should be going directly to the museum. The Foundation countered that some of their fundraising efforts had to go to paying off the Taper loan, which ALPLM administrators had repeatedly weakened their ability to do. In addition, it takes money to raise money. The Foundation had a staff of their own that they needed to pay.

The operating agreement between the ALPLM and the Foundation was due to expire in January of 2021, but was extended as the two were in talks about its replacement. In previous years, the agreement had always been renewed without any real changes. This time, however, the ALPLM interim directors wanted significant changes to increase their oversight and control of the Foundation. The Foundation refused these changes, saying that they were not a department of the State of Illinois and that they were supposed to be a separate partner. The Foundation thought they were still in talks with the ALPLM when, on April 1, 2021, the ALPLM publicly declared that they were no longer affiliated with the Foundation.

Despite the public declaration, the Foundation still hoped that a reconciliation could occur, especially since a new, permanent director of the ALPLM was set to start in June. Unfortunately, even after the new director, Christina Shutt, took over the ALPLM, no reconciliation occurred.

The ALPLM essentially divorced the Foundation, and so the Foundation moved on. In 2022, they rebranded themselves from the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation to the Lincoln Presidential Foundation. Their mission of supporting the education of Abraham Lincoln’s legacy remained the same, but they now opened themselves up to working with multiple sites and organizations. Their updated website states, “the Lincoln Presidential Foundation…will support, sustain, and provide educational and public programming, research, and access to historic places and collections, all related to the life and legacy of Abraham Lincoln, with new partners and collaborators near and far.” The first of the Foundation’s new partners is the National Park Service, with the Foundation currently providing financial support to the Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield.

Thus, we finally reach October 31, 2022. That was the date that the loan agreement for the Taper collection between the Foundation and the ALPLM was set to expire. While in previous years the loan to house the Taper collection at the ALPLM was renewed with no issue, the situation had now drastically changed. Those in power at the ALPLM had battered the Foundation for years and then publicly divorced them the year before. The only thing left for the Foundation to do was to pick up their things from their ex’s house. The cruel irony of it all is, if the different directors of the ALPLM hadn’t sabotaged the Foundation’s efforts to pay off the Taper loan, there likely would have been nothing for the Foundation to take. Once the loan was paid off, the items would have been officially donated to the ALPLM, and the Foundation would have no more claim to them.

However, because the Foundation still owed the bank, the entire 1,500-piece collection was theirs to take back. What the Foundation will do with the Taper collection now, especially since they still owe several million dollars on the loan, is unknown. Some of the non-Lincoln-related parts of the collection were actually already sold off at one point to help pay down the loan, so it’s possible the Foundation might sell off some more to pay off the remaining debt.

The Pointlessness

None of this needed to happen. The Taper collection would be sitting in the ALPLM and owned by the State of Illinois right now if it weren’t for people in political patronage positions fighting for power at the expense of history. Mistakes were certainly made at the beginning of all of this. Louise Taper shouldn’t have put the time pressure on the Foundation board (of which she was a member) to purchase her collection while also preventing them from seeing her full appraisal until after they had a buyer’s agreement. Despite having worked with part of it for years, Dr. Thomas Schwartz failed to properly vet and research pieces in his friend’s collection. He, therefore, did not accurately advise the Foundation on its contents. If proper research had been done on the hat prior to the purchase, it is very unlikely the Foundation would have paid $6.5 million for it.

And yet, someone overpaying for a questionable historic artifact is no great crime. Auction houses make their living on artifacts with all sorts of provenance. While the Foundation overpaid for the hat (and perhaps a few more items with similar provenance), the majority of the Taper collection was still worth the purchase. The hat was a sloppy mistake, but didn’t have to be a fatal one. Unfortunately, the ALPLM failed to be honest about the hat after its acquisition. Dr Schwartz and Dr. Cornelius, not being able to find supporting documentation for the provenance they had, decided to replace it with a story they found more plausible. Their failure to be honest about the hat’s questionable provenance and their devotion to their unsupported theory provided the ammunition for the political attacks that followed.

ALPLM administrators were unceasing in their war against their own Foundation. Evidence indicates they leaked information to the press in an effort to weaken their enemy, not understanding that they were cutting off their own nose to spite their face. Not only have their actions led to the removal of a truly remarkable collection of artifacts, but they have also irrevocably damaged the ALPLM going forward. The Foundation provided tens of millions in supplemental funds and support to the ALPLM, whose only other funding is the taxpayers of the state of Illinois. Until the divorce, the Foundation was always there helping to purchase artifacts, fund special exhibits, buy replacement equipment for the museum’s stage shows, and enact special programming to draw in donors and volunteers. The Foundation’s sole job was to be a partner to the ALPLM and help it get more money. And yet, leaders of the ALPLM couldn’t accept that the Foundation had to keep a lot of the money they raised to pay for their own expenses (like the Taper debt). In the end, the leaders of the ALPLM wanted all the money the Foundation raised, which just isn’t possible. Rather than being thankful and appreciative of what their partner could provide, the leaders of the ALPLM took the drastic action of attacking and eventually divorcing the Foundation. Now, more than ever, they will be deeply impacted by the whim of the State of Illinois’ often precarious budgets. They now also lack a strong ally to help them successfully fund expensive building improvements and exhibit redesigns, something the 17-year-old museum will have to do sooner rather than later if they are to remain relevant.

All of this makes me extremely sad. I love the ALPLM. It is a truly remarkable museum with amazing staff and volunteers. Unfortunately, those in power have, time and time again, acted against the best interest of the museum and its mission to educate and preserve the legacy of Abraham Lincoln. Unless the ALPLM is able to clean house of its toxic political patronage element, I worry about its future as an institution.

As far as the Taper collection goes, I hope the Foundation can find a home for it, and worry that some of it will be sold to pay off the remaining debt. As an assassination historian, I fear that if push comes to shove, the Booth-related objects might be selected as the things the Foundation might be willing to part with due to their connection to Lincoln’s assassin. It would be a loss to future assassination historians and researchers for these items to be scattered into private hands once again.

In conclusion, I invite you to click here or on the image below to view a partial list of the items in the Taper collection. This was part of the original transmittal document that the ALPLM received from Taper after the purchase. The Booth materials span pages 55 – 104. Unfortunately, the document cuts off right at the Assassination materials, so I do not have a full accounting of those materials.

In addition, the ALPLM has about 600 documents from the Taper collection digitized and still up on their Chronicling Illinois website. I feel it is likely this collection will come down in the future, so I recommend looking through and saving parts of it now, before it is removed. You can click the image below to view the digitized documents.

Reading through the list and seeing the digitized documents really demonstrates how much the ALPLM lost due to their leaders’ feud with their own Foundation. For now, all we can do is sit back and see what the Foundation decides to do with the Taper collection and what action they think is best to help settle the remaining debt. My sincerest hope is that they will find a way to keep the collection together and accessible.

Only time will tell the true fate of the Taper collection.

TL;DR (Too Long; Didn;t Read) Summary

- The Louise Taper collection contains about 1,500 artifacts and documents relating to Abraham Lincoln.

- One of the items in the collection is a stovepipe hat, said to have belonged to Abraham Lincoln. However, the only supporting provenance is an affidavit from a woman named Clara Waller who stated her father-in-law exchanged hats with Lincoln in D.C. during the Civil War.

- Louise Taper put the board of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation under a time crunch to purchase her collection in 2006/2007, citing another interested party who had the capital ready to go.

- Both the Foundation and the ALPLM were headed by the same individual who had a vested interest in acquiring the collection for the museum,m which, at that time, had a lack of physical artifacts.

- The appraiser sent by the Foundation to look at the Taper collection was not tasked with looking into the provenance of the items due to the time constraints and because he was informed the collection had already been historically vetted by historians at the ALPLM.

- Dr. Thomas Schwartz, the ALPLM historian who vouched for the collection as a whole, was a friend of Louise Taper and did not know the item-by-item provenance of every item in her collection at the time of the sale.

- The hat had been loaned to the ALPLM and other exhibitions around the country (and the world) prior to the purchase, with no one looking into its provenance.

- Dr. Schwartz knew that the Lincoln stovepipe hat had been owned by his mentor, James Hickey, the former Lincoln Curator. Dr. Schwartz trusted Hickey’s expertise in Lincoln and assumed that he would only have purchased the hat if its provenance was not in question.

- The Taper collection was bought by the Foundation for $23 million and loaned to the ALPLM until such time as the bank debt was paid, at which time the collection was to be formally donated to the museum.

- Initial research into the provenance was conducted by Dr. Schwartz and Dr. James Cornelius, the Lincoln Curator at the ALPLM, with no new information found.

- The pair of historians decided, without evidence, that it was more plausible for the Southern Illinois farmer to have received the hat during an 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debate in Jonesboro, IL, rather than in D.C. during the Civil War. They began citing this story when asked about the hat.

- Eileen Mackevich, the director of the ALPLM from 2010 -2015, had a feud with the Foundation and an adversarial relationship with its director, Dr. Carla Knorowski.

- According to the recollections of an ALPLM deputy director, Director Mackevich contacted the press to tip them off about the hat’s questionable provenance in an effort to publicly damage the Foundation’s reputation.

- When asked about the hat, Dr. James Cornelius and the ALPLM doubled down on the theory that the hat came from a Lincoln-Douglas debate. They produced a document defending the hat that was filled with untruths.

- The Foundation did their own investigation into the hat by having representatives from the Smithsonian and the Chicago History Museum, two institutions that both have a Lincoln stovepipe hat of their own with varying provenances. These representatives concluded that the Waller provenance was insufficient to prove the hat belonged to Lincoln and recommended that the museum take a less defensive approach going forward.

- The Foundation had the hat tested for DNA by the F.B.I. This testing was done secretly without the knowledge of anyone at the ALPLM except for Dr. Cornelius, who assisted. No nineteenth-century DNA was found on the hat.

- In 2016, Foundation director Dr. Carla Knorowski and Dr. Cornelius published a book about some of the artifacts in the ALPLM collection titled Under Lincoln’s Hat. The hat was portrayed as Lincoln’s without any qualification.

- Alan Lowe was appointed the new ALPLM director in July 2016. He and his advisors maintained the difficult relationship with the Foundation that had started under Eileen Mackevich.

- Lowe was not made aware of the FBI report until January 2018. He likewise did not learn of the report from the museum representatives until August.

- In August, Director Lowe tasked Illinois State Historian Dr. Samuel Wheeler with investigating the history of the hat and Taper purchase.

- In September, the press reported on the FBI and museum representatives’ reports. Lowe accused the Foundation of essentially lying to him (and the public) about the hat.

- That same month, Dr. James Cornelius resigned from the ALPLM. He had been on administrative leave since March.

- In October, Lowe announced to the AP that he had dissolved his $25,000-a-year consultancy contract with the Foundation. In the months to come, he would prohibit members of the ALPLM staff from talking directly to the Foundation.

- In May 2019, Dr. Wheeler requested a textile expert to look at the hat. This was the first time the Foundation had heard that another investigation of the hat was ongoing. They requested a meeting with Lowe to be brought up to date and collaboratively plan next steps. Lowe did not respond to their request.

- The Foundation failed in their attempt to receive funds from the Illinois State Assembly to help pay off the remaining Taper debt. Lowe halted Dr. Wheeler’s research into the hat.

- In June 2019, though the research into the hat was incomplete, Lowe wrote an email to the Deputy Governor stating, “…the state historian that he and his team have found no evidence confirming the hat belonged to President Lincoln.” This email was acquired by reporter Dave McKinney through a conveniently specific FOIA request, resulting in another damaging article in September 2019.

- Alan Lowe was fired from the ALPLM in September for having “pimped out” the ALPLM’s copy of the Gettysburg Address written by Abraham Lincoln to political commentator Glenn Beck.

- Dr. Wheeler was given a deadline by the interim administrators of the ALPLM and the Deputy Governor to put his findings on the hat in writing, despite his research being incomplete

- Dr. Wheeler presented his research to a joint meeting of the new ALPLM board, the Foundation, and the Deputy Governor. The Foundation suggested Dr. Wheeler access their files regarding the Taper purchase, which was allowed, and Dr. Wheeler was given an extension on his final report.

- Dr. Wheeler turned in his report, documenting the years of fighting between the ALPLM and the Foundation on December 16, 2019.

- On January 20, 2020, the ALPLM and Foundation boards agreed to take Dr. Wheeler’s suggestion to create a joint committee to further study the hat.

- Due to a delay brought on by COVID-19, the first joint committee session met virtually on July 7, 2020, and agreed to split the cost of a textile expert to assess the hat.

- On July 15, 2020, Dr. Samuel Wheeler was removed as the Illinois State Historian.

- The interim leaders of the ALPLM seized Dr. Wheeler’s research notes on the hat. The joint committee that had agreed to bring in the textile expert never did so. The committee appears to have been disbanded.

- The same interim leaders continued their war against the Foundation, eventually using legislative means to divorce the ALPLM from the Foundation completely in April 2021.

- The Foundation, no longer tied to the ALPLM, rebranded themselves and began looking for other Lincoln partners to support.

- On October 31, 2022, the loan agreement for the Taper collection housed at the ALPLM expired. The Foundation removed the collection.

- The collection was sent to an auction house in Chicago, but there has been no word as to its future.

- UPDATE: On May 21, 2025, 144 lots of the former Taper Collection will be sold by Freeman’s | Hindman Auctions

You can read Dr. Wheeler’s full report for yourself here.

Recent Comments