The Abraham Lincoln Home in Springfield, IL and the Petersen House in Washington, D.C. have shared similar histories.

- Both homes witnessed the death of a Lincoln:

On February 1st, 1850, Eddie Lincoln, the second son of Abraham and Mary Todd, died at the age of 3 at the Lincoln Home in Springfield.

On April 15th, 1865 at 7:22 am, President Abraham Lincoln died at the age of 56 at the Petersen House in Washington, D.C.

- Both homes had few owners:

The Lincoln Home was built in 1839 for the Reverend Charles Dresser. The Lincolns bought it from him in 1844. Robert Todd Lincoln inherited the property from his parents and he subsequently gave it to the government in 1887. This gives the Lincoln home two owners, Rev. Dresser and the Lincoln family, before it was purchased by the government.

The Petersen House was commissioned by William and Anna Petersen in 1849 and built that same year. When they died in 1871, the house was inherited by their children. They sold the house to Louis Schade in 1878. By 1896, Louis Schade sold the house to the government for $30,000. This gives the Petersen House two owners, the Petersens and Louis Schade, before it was purchased by the government.

- Both homes had considerable remodeling done when their namesakes lived there:

The Lincoln Home had about 5 renovations while the Lincolns lived there. Most drastically was the alteration of the home from a 1 ½ story structure to a full 2 story home, as it still is today.

The room that would later be known as the room where Lincoln died, was not even part of the Petersen House when it was originally built. That addition was put on in 1858. Fire gutted it in 1863 and William Petersen rebuilt it that same year.

When Abraham Lincoln was elected President and moved into the White House, he rented out his Springfield home. When Robert Todd gained ownership of the place, he continued the practice of renting the house out until he gave it to the government.

The Petersens ran their home as a boarding house for many years. From Congressmen to soldiers, to actors, they rented out rooms to many needy Washingtonians.

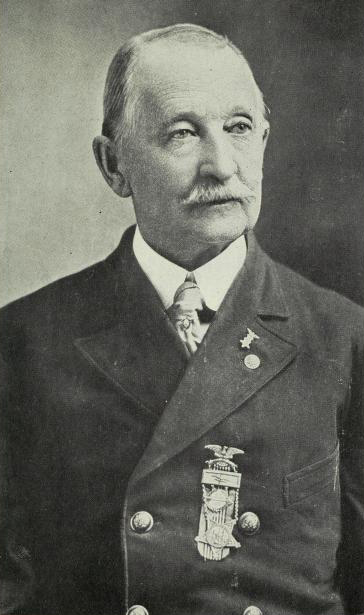

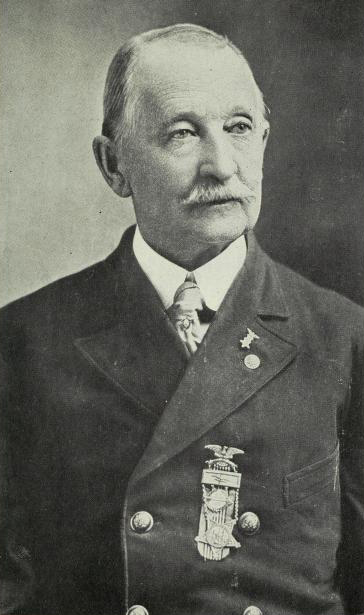

- Lastly, both homes shared a long-term occupant, Osborn Hamilton Ingham Oldroyd:

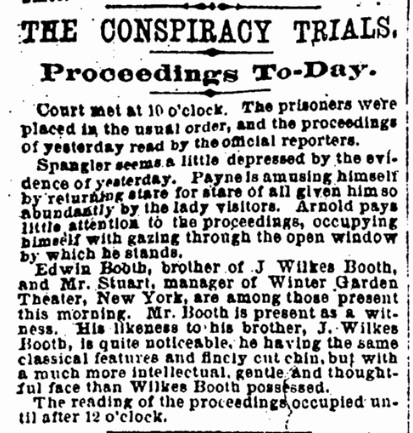

Osborn Oldroyd was a Civil War veteran and a devoted collector of Lincoln memorabilia. In 1883, 41 year-old Oldroyd succeeded in fulfilling the dream of any man who idols another. Robert Todd Lincoln made Oldroyd the fifth renter of the Lincoln Home in Springfield since his father left the city to claim the Presidency. Into this historic house, Oldroyd brought his vast collection of nearly 2,000 Lincoln items. As had been commonplace since the death of Lincoln, many visitors came to call on the Lincoln Home, seeking to visit the home of the great martyr. Oldroyd let them in like all of his predecessors had, but was the first to charge them admission. He turned his collection and rented space in a Lincoln Museum. Robert Todd accepted this exploitation as long as Oldroyd paid his rent, however, by 1885, Oldroyd was starting to fall behind his payments. Despite not paying him, Robert Todd did not want to bring a lawsuit against Oldroyd as he feared it, “may easily cause me more personal annoyance than the loss of ten times the money.” Rumors spread that Oldroyd was also cutting off parts of the curtains, wallpaper, and flooring, selling them as souvenirs. Robert Todd was getting angry with his tenant whom he referred to as a “dead beat” and “rascal”, when an Illinois legislative committee approached him in 1887 to purchase the Lincoln Home. A similar offer had been given to him in 1883, but at that time he had declined. Even though, Robert Todd was fairly certain Oldroyd had been the catalyst for this offer, he decided to donate the property to the state of Illinois. His donation contained two caveats, however. “…Said homestead shall be, forever, kept in good repair and free of access to the public.” This latter requirement was probably meant as a final jab towards his “rascal” of a tenant and his entrepreneurial exploits. Regardless, Osborn Oldroyd was hired by the state of Illinois to be the first custodian of the house and gave him a salary of $1,000 per year. Oldroyd undoubtedly used this salary to increase his collection at every turn.

Oldroyd’s tenure at the Lincoln Home came to an end in 1893 when he was fired by recently elected Gov. John Peter Altgeld. Altgeld replaced him with a political friend named Herman Hofferkamp. Out of a cushy job and a free place to live, Oldroyd was in trouble. Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., the Schade family had moved out of the Petersen House apparently fed up with the number of visitors constantly asking to see the death room of the President. They leased the building to the Memorial Association of the District of Columbia, a group formed by Congress the year before. When and how Oldroyd managed to convinced this group to make him custodian of the Petersen House is unknown. According to a biography about Oldroyd written when he was alive, in 1893 Oldroyd moved his collection to the Petersen House, “at the request” of the association. The earliest account the NPS has managed to find of Oldroyd residing at the Petersen House is June of 1898. This was after the government purchased the house outright from the Schades in 1896. So, whether Oldroyd went straight from the Lincoln Home to the Petersen House, or whether he had five years in between, he ultimately found a new location to show off his collection.

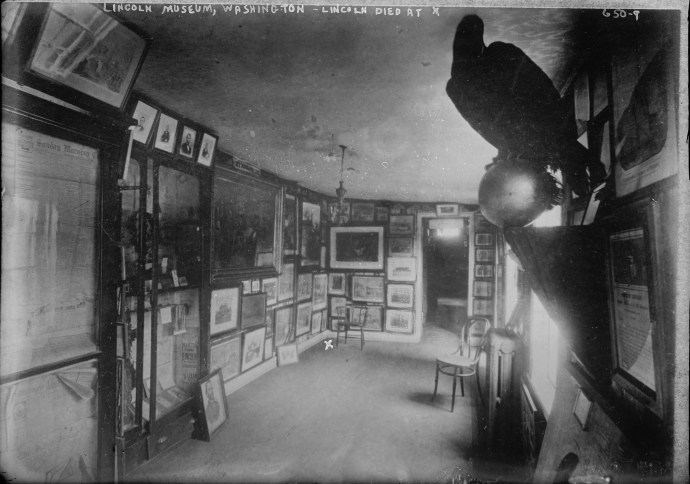

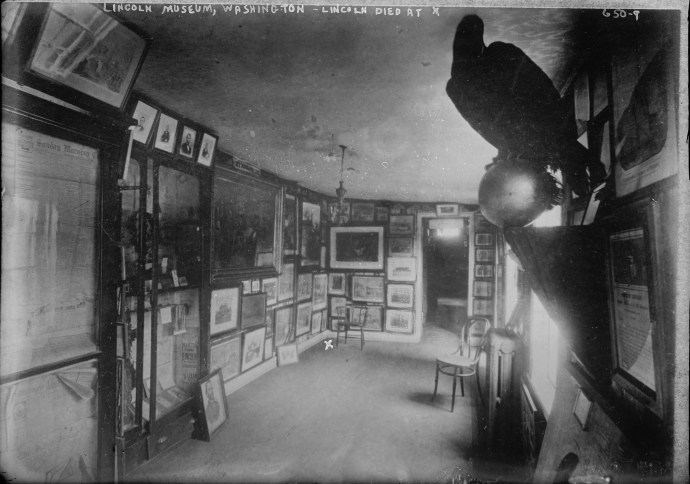

While he lived rent free at the Petersen House, Oldroyd did not receive a salary there. Instead, he got back to his roots and was allowed to charge admission to his museum. He made the whole first floor of the house his exhibit floor and he and his family lived upstairs. The first floor of the Petersen House contained considerably less real estate than what he had previously used to showcase his collection at the Lincoln Home. He covered practically every surface of the Peterson House with material to make up for it. Oldroyd also had a lot of changes made to the building while he lived there. Most noticeably, he had the back wall of the room where Lincoln died, removed.

The following are some pictures of the interior of the Petersen House when it housed Osborn Oldroyd’s Lincoln Museum:

This picture was taken from within the front parlor of the Petersen House facing towards the rear parlor. The door to the right leads into the hallway with the room where Lincoln died at one end and the entrance to the Petersen House at the other.

This photo was taken from within the rear parlor of the Petersen House in the direction of the front parlor. This photo shows only the front parlor.

This photo was taken from the entrance of the room where Lincoln died. The bed Lincoln died in would have been located in the bottom right hand corner of this photo.

This photo was taken from the rear of the room where Lincoln died in the direction of hallway and Petersen House entrance. The X marks the location of Lincoln’s deathbed.

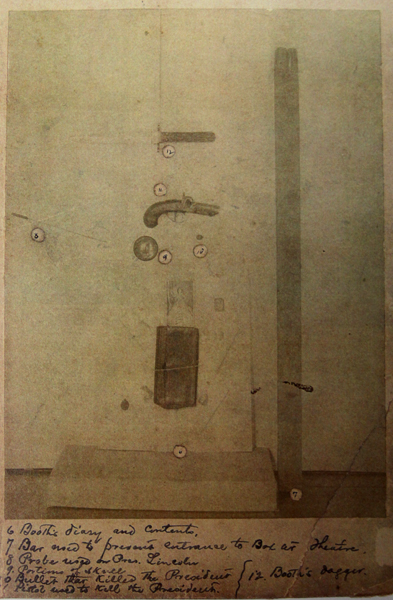

During his tenure at the Petersen House, Oldroyd continued to collect and correspond with many individuals associated with Lincoln’s life and death. In 1901, after walking the escape route of Lincoln’s assassin on foot with a camera, he published his book, “The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln”. This volume contains many of the earliest photographs we have of different parts of the escape route.

By 1926, after about 30 years curating his collection at Petersen House, Oldroyd sought the help of Congressman Henry Rathbone of Illinois, to insure its preservation. The son of Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris, the ill fated pair who joined Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre that night, managed to pass a bill in Congress authorizing the purchasing of Oldroyd’s collection. Experts at the Smithsonian noted that the collection “was of little practical value”. Despite this, Oldroyd was paid $50,000. Oldroyd later stated that he had been offered far greater amounts for the collection by private individuals but that he wanted the collection to be in the hands of the government so that it would be preserved and enjoyed by the public for years to come. When offered continued curatorship over the collection Oldroyd replied, “the responsibility would be too much for me to assume at my age of eighty-four years.” Oldroyd was then given the key to the Petersen House and told that he was free to come and go as he pleased and that his accustom chair would always be there for him.

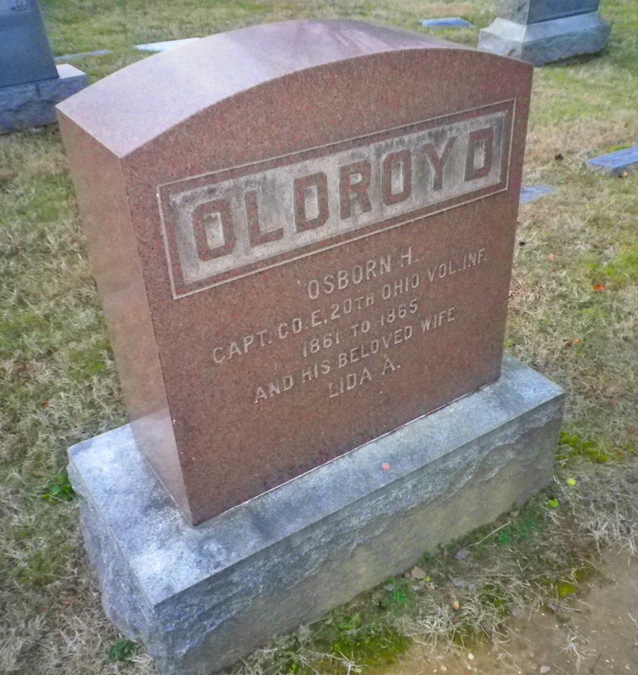

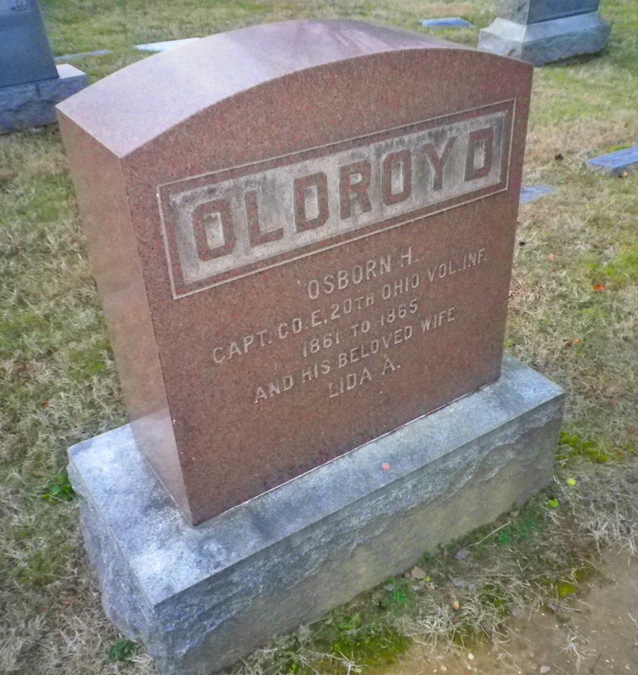

Osborn Hamilton Ingham Oldroyd died four years later in 1930. He is buried next to his wife of over 54 years, Lida, at Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

He may have been a “rascal” as Robert Todd Lincoln called him, but Osborn Oldroyd was also the epitome of a collector. He devoted his whole life to acquiring everything relating to Abraham Lincoln. For nearly half of his life, Osborn Oldroyd made his home in houses relating to the 16th President. To the collection and study of Lincoln, Osborn Oldroyd’s name is unavoidable, particularly in the study of his assassination. I find it entirely appropriate then, that in this picture of Rep. Henry Rathbone in front of the Petersen House Lincoln Museum, the presence of Osborn Oldroyd in his favored setting is enshrined forever:

References:

House Where Lincoln Died Historic Structures Report by the National Parks Service

Life of Osborn H. Oldroyd by William Burton Benham

Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert Todd Lincoln by Jason Emerson

Lincoln Home National Historic Site

The Lincoln Assassination: Where Are They Now? by Jim Garrett and Rich Smyth

Recent Comments