After my last post about the whole Booth family living under one roof during the 1860 census, Art Loux posed an interesting question:

Has anyone found the Booths in the 1870 census? I have looked for Mary Ann, Rosalie, Edwin and Joseph but have not found any of them. Asia was in England.

I decided to see if I could find an answer for him. I decided to look for Edwin first, hoping the rest of the family would be with him. As a popular actor, I figured he would be the easiest one to track down. Having recently bought Arthur Bloom’s wonderful new book, Edwin Booth: A Biography and Performance History, I figured I’d have the answer in just a half hours work. Boy was I wrong. After a couple days of pouring over census pages, I’ve still come up empty trying to find the greatest Hamlet of his generation in the 1870 census. However, I have two ideas as to why I haven’t been able to find him: Either Edwin missed the census or the census missed him.

First, utilizing Bloom’s biography of Edwin, let’s discuss Edwin Booth’s life leading up to the 1870 census.

1867 – 1869:

The three years previous to the census were very formative years in the life of Edwin Booth. In June of 1867, Edwin purchased four adjacent land plots at the intersection of 6th avenue and 23rd street in New York City. It was here, that Booth invested his fortune to build his own theatre, Booth’s Theatre. Though Booth managed the building of the theater, he spent little time witnessing the progress on it. Instead, he spent the acting seasons of 1867-1868 and 1868-1869 touring in order to fund the project. He had hoped to have the theatre ready to go by December of 1868, but delays pushed back the grand opening of his theatre until February 3rd, 1869. He opened his namesake theatre with Romeo and Juliet.

Booth’s Theatre

Shortly after the theatre opened for business, Edwin most likely read in the papers about the presidential pardon of Dr. Mudd for his involvement in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Pardons for conspirators Samuel Arnold and Edman Spangler followed soon after. Seven days after his theatre’s debut, Edwin Booth wrote to President Andrew Johnson asking, again, for the remains of his misguided brother. Edwin was successful this time, but he did not go to Washington, sending his brother and business manager Joseph in his stead.

During this period, Edwin had fallen in love again. Mary Devlin, Edwin’s first wife and mother of his only child, Edwina, had died in 1863. The new object of Booth’s affection was Mary McVicke. Mary was the step-daughter of James McVicker, the actor and owner of McVicker’s Theatre in Chicago. In mid-1867, Booth offered Mary McVicker the role of his leading lady for the 1867-1868 season. In truth, McVicker was hardly experienced enough to be a leading lady, but Edwin was smitten with the 19 year old. They toured together and by the summer of 1868, Edwin and Mary McVicker were living together. They finally made the arraignment official and married on June 7th, 1869, four months after the opening of Booth’s Theatre. By October of 1869, Mary was pregnant.

Edwin and Mary (McVicker) Booth

From Bloom’s biography and newspaper accounts, we learn that during this time period Edwin and Mary were living in Booth’s Theatre in a suite of rooms.

When the summer months rolled around, Edwin and Mary liked to vacation at Long Branch, New Jersey. Long Branch had been a beach resort town since the late 18th century. By the 19th century, it had become a “Hollywood” of the east coast, with many actors (particularly those from New York) calling Long Branch their summer home. In fact, Mary’s stepfather, James McVicker, owned a home in Long Branch and the family would summer there.

During the 1869 -1870 theatrical season, Edwin needed to make more money to help repay his debts from building Booth’s Theatre and therefore went touring. Pregnant Mary joined her husband as he travelled to Philadelphia, Boston, and other New England cities. By January of 1870, the Booths were back at their own theatre. Edwin’s next documented performance outside of New York was not until the 1870 – 1871 season.

1870:

After a great deal of researching here is my timeline for Edwin Booth for the year of 1870, the census year.

January – April, 1870 – Edwin and Mary are at home, living in Booth’s Theatre on the corner of 6th avenue and 23rd street, NYC. Edwin is performing in his own theatre.

April 16th, 1870 – Edwin’s last performance at Booth’s Theatre for the 1869 – 1870 season.

May 1870 – Edwin and (most likely) the pregnant Mary travel to Long Branch, New Jersey for a brief vacation before the baby is due in June. Newspaper clippings support the idea that Edwin was in Long Branch.

May 30th, 1870 – James McVicker, Mary’s stepfather, opens at Booth’s Theatre in a new play called “Taking the Chances”.

Early June, 1870 – Edwin and Mary return to their home above Booth’s Theatre in New York.

June 13th, 1870 – Edwin writes a letter to Jervis McEntee from New York, verifying that he is back home.

June, 1870 – Per Bloom’s biography: “Edwin and Mary were married in June 1869, and by late October she was pregnant. The baby was almost a month late. The doctors in attendance convinced the Booths that Mary miscalculated. They all thought it was a joke, but the result was a disaster.” If the couple expected the baby was going to be born in June, this would explain why they left Long Branch after only spending a month there. Since Mr. McVicker was playing at Booth’s Theatre, it would make sense that he would want to witness the birth of his (step) grandchild.

July 3rd, 1870 – Per Bloom: “Mary was a physically small woman, and the baby was so large (10- ½ pounds) that the attending doctors were forced to use forceps, which slipped twice and damaged the child’s head. Edwin assisted at the birth, which came at 11:30 p.m. on July 3, 1870.” By 4 a.m. the baby, named Edgar, had died. The birth occurred at home in Booth’s Theatre.

July, 1870 – The birth was hard on Mary, and she was sedated with chloroform for five days after. During her sedation, Edwin buried Edgar next to his first wife, Mary Devlin, in Massachusetts. When he came back, he took Mary back to Long Branch to recover, likely with the McVickers in tow.

July 25th, 1870 – A letter written by Edwin Booth to Jervis McEntee from Long Branch, NJ, verifies that Booth was back at Long Branch.

August 20th, 1870 – A letter written by Edwin Booth to Charles Gayler (the playwright for the play Mr. McVicker had debited in May) from Long Branch, NJ, verifies that the couple was still at Long Branch.

September 5th, 1870 – Edwin Booth starts the 1870 – 1871 season at McVicker’s Theatre in Chicago. Mary, now recovered from the after effects of childbirth, accompanies him, and her parents, there.

October – December, 1870 – Edwin Booth acts in St. Louis, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia.

December 16th, 1870 – Booth is in Philadelphia playing at the Walnut Street Theatre. Edwin wrote to a friend on this date stating, “I shall be home at Xmas (God willing) and will follow Jefferson at Booth’s in Jan. This is rather unexpected, tho’ I’m rather glad of it, for I am sick of traveling, and it is not the thing for Mary, who has been confined to the house for a week past…” It appears Mary had continued to follow Edwin during his entire tour.

December 24th, 1870 – Edwin’s last performance in Philadelphia. Edwin and Mary assumedly go home to New York. Edwin starts playing at his own theatre starting January 9th, 1871.

Theories:

With the timeline above, I have two theories as to what happened with Edwin Booth and the census.

1. Edwin Booth missed the census.

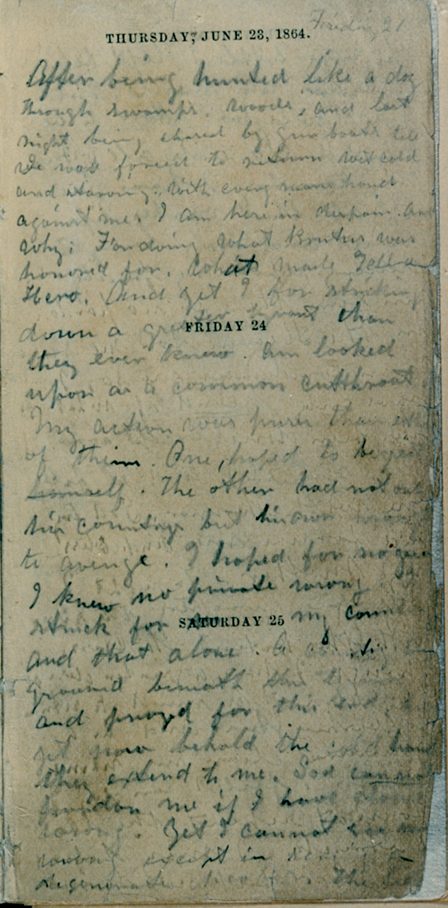

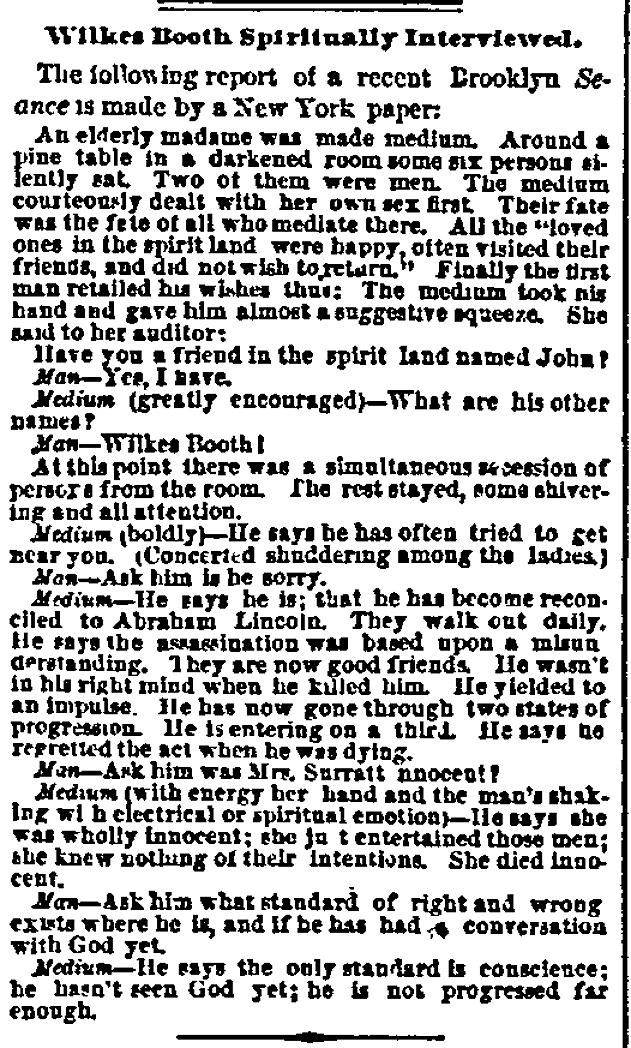

According to Ancestry.com: “The official enumeration day of the 1870 census was 1 June 1870. All questions asked were supposed to refer to that date. The 1870 census form called for the dwelling houses to be numbered in the order of visitation; families numbered in order of visitation; and the name of every person whose place of abode on the first day of June 1870 was with the family.” From newspaper accounts, we know that Edwin Booth was in Long Branch, NJ in May. From a letter Booth wrote on June 13th, we know that he was then back in New York. Two possible scenarios would eliminate Edwin Booth from being counted. Either Edwin was still in Long Branch when his neighborhood was surveyed or Edwin was back in New York when the census enumerators came, but since he had been living in Long Branch on June 1st, they did not include him. Two identical newspaper clippings from two different papers make a joke that supports the idea that Edwin Booth missed the census:

2. The census missed Edwin Booth

The 1870 census was not without controversy. After it was completed many states, including New York, believed that large portions of the population had been missed. Could Edwin Booth have been one of those who were missed? It may not be as ridiculous as it sounds. Mary Booth’s step father, James McVicker, was engaged at Booth’s Theatre from May 30th – June 11th performing in “Taking the Chances”. Though I’ve not yet found documentation for it yet, it is extremely likely that Mr. McVicker stayed on at Booth’s Theatre to await the birth of his (step) grandchild. This puts Mr. McVicker in New York City from May 30th to at least July 3rd. If census takers surveyed him, he could honestly say he was living in NYC on June 1st and he would have been included. However, like Edwin Booth, James McVicker is nowhere to be found in the 1870 census. He’s not in New York City, he’s not in Long Branch, he’s not back home in Chicago. Nor is there any record for Mrs. McVicker in the 1870 census either. Perhaps the 1870 census actually missed Edwin Booth and his entire household.

The weirdest part of all of this is that, barring an obvious mistake by me, the Booths had to have been missed not once, but twice. New York City was given permission to do a recount of the 1870 census and started a 2nd enumeration in December of 1870. Edwin would have been at home when the enumerators were in his neighborhood in early January, but again, there is no record of him. Perhaps, living in his own theater as he did, the census people did not think to knock on the theatre doors and ask about anyone living there.

The Rest of the Family:

While I was not successful in finding Edwin Booth for Art, I did find Mary Ann, Rosalie, and Joe. The three of them were not living at the Booth Theatre. In August of 1869, Edwin wrote a letter to a friend in which he stated, “I sold my house some weeks ago—obtained comfortable quarters for my brother and sister— with whom Joe resides…” The “Joe” Edwin names is not his brother, but rather actor Joseph Jefferson. When this letter was written, Joe Jefferson was performing his famous Rip Van Winkle character at Booth’s Theatre. This helped me place the residence of the Booth family somewhat close to the Theatre. When I found the following census record for a “Maria”, Rosalie, and Joseph Booth, boarding less than a mile from Booth’s Theatre down 6th avenue, I knew I had found the right family.

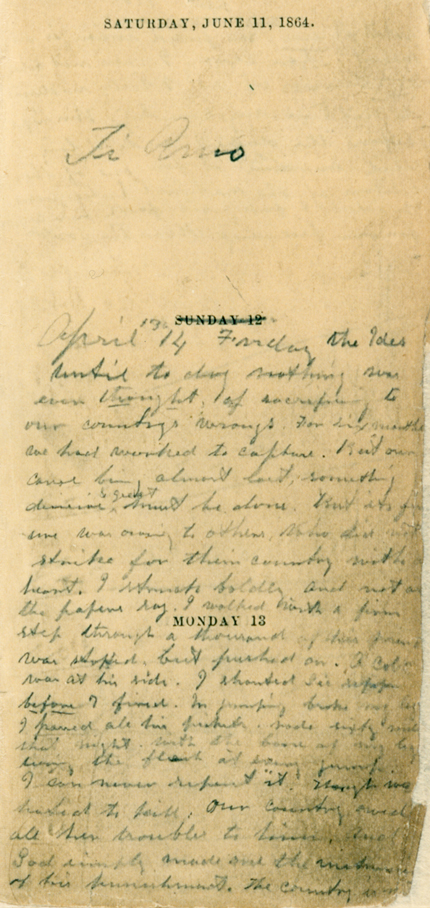

Mary Ann, Rosalie, and Joseph Booth in the 1870 Census. Click the image for the full page.

They all decided to fudge their ages a bit. In reality, Mary Ann was 68, Rosalie was 47, and Joe was 30. Oh vanity, thy name is Booth.

Conclusion:

If I have completely wasted my time and Edwin is actually in the 1870 census, plain as day, I welcome the correction. I’d be embarrassed for missing him, of course, but I’d rather know.

Despite his fame and fortune, Edwin Booth has proven to be an elusive man. Though I’ve come up empty handed trying to find him in the 1870 census, the process of searching for him has taught me more about his life around that period than I would ever have known otherwise. I searched the records, documented Edwin’s movements and read hours’ worth of census pages. The search for knowledge is what makes this all worthwhile. Still, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to go and take a nap until the next census to recover. Or maybe a vacation would do me some good. I’ve read Long Branch, NJ is nice.

References:

Edwin Booth: A Biography and Performance History by Arthur Bloom

The 1870 Federal Census accessed through Ancestry.com

Newspaper articles from GenealogyBank.com

The Hampton-Booth Theatre Library online card catalog

Letters from Edwin Booth to John E. Russell from The Outlook magazine April 20st, 1921

Recent Comments