Last month, I published a post containing an episode of The Twilight Zone Podcast in which the host, Tom Elliot, included two radio shows based on the concept of time travel and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. That podcast episode was a prelude to Tom’s regular review of “Back There,” an episode of The Twilight Zone, which deals with the very same topic. I very much enjoyed listening to both of Tom’s podcasts, and they inspired me to do my own analysis of one of my favorite episodes of this iconic series. What follows is an exploration of “Back There,” containing an overview of the episode, biographies of the actors who took part in it, a look into the production and editing, some trivia, and a discussion of some other adaptations of this unique Lincoln assassination-related show. While the following post isn’t quite as “vast as space, or as timeless as infinity,” it is still quite a deep dive. If you’re ready for such an adventure into the fifth dimension, then read on as we travel “Back There” with The Twilight Zone.

Contents

Episode Overview

“You’re traveling through another dimension. A dimension not only of sight and sound, but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination. That’s the signpost up ahead. Your next stop, The Twilight Zone.”

The episode opens with an establishing shot of a building bearing the sign “The Potomac Club. Established 1858.” We fade to the interior of the club and find it to be a traditional gentlemen’s club in the year 1961. The decor is ornate, with various sculptures and paintings throughout the room. There are several seated men around the periphery of the room reading newspapers and playing chess. The club attendants dutifully move around the room, serving drinks to the members. Near the center of the drawing room is a round table with four men seated around it playing cards.

The camera pushes in on these men, and we begin to overhear their conversation. One of the members at the table named Millard has espoused his belief that if someone had the ability to travel back in time, nothing would stop them from changing the past. Specifically, Millard suggests traveling to the day before the stock market crash of 1929 and taking action to prevent financial disaster. A younger member of the group named Peter Corrigan is skeptical of the idea, noting he would be an anachronism in the past and that he really wouldn’t belong back there. He comes to the conclusion that an event like the stock market crash of 1929 is a fixed event in history that couldn’t be altered. Millard disagrees and continues explaining what actions he would take if he were to travel to 1929. The camera then pans over to reveal that one of the seated gentlemen reading a newspaper is none other than Rod Serling. He then gives the show’s opening narration:

“Witness a theoretical argument, Washington, D.C., the present. Four intelligent men talking about an improbable thing like going back in time. A friendly debate revolving around a simple issue, could a human being change what has happened before? Interesting and theoretical because who ever heard of a man going back in time? Before tonight, that is. Because, this is, the Twilight Zone.”

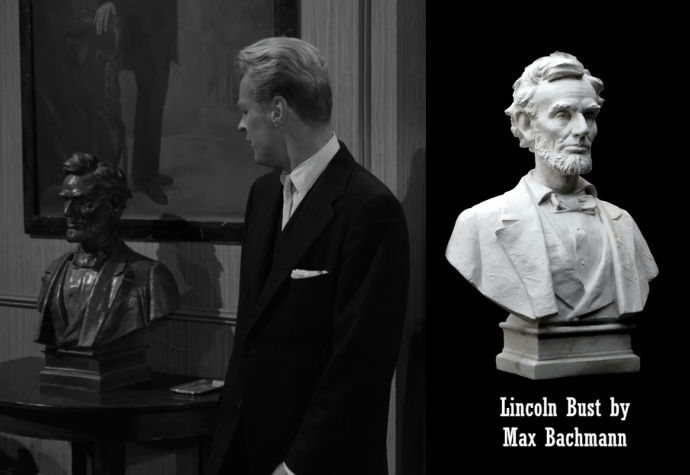

When we fade back in, Corrigan tells the group that he is going to retire for the evening, noting that he will leave the subject of time travel to the likes of H. G. Wells. Whitaker, one of the card players, bids him goodnight by joking, “Don’t get lost back in time, now, Corrigan.” After Corrigan bids farewell to the other gentlemen, he exits into the foyer of the Potomac Club. On a side table rests a bust of Abraham Lincoln. Corrigan turns and glances at the Lincoln bust. At the same time, one of the club’s attendants, William, is carrying a plate with a teacup of coffee. With Corrigan focusing on the Lincoln bust and William on the cup, the two men accidentally collide, causing William to spill the coffee over them both.

William is very apologetic and attempts to clean off Corrigan’s suit jacket with a handkerchief. Corrigan understands it’s an accident and takes it in stride. William offers to get Corrigan’s coat, but Corrigan states that he was rushing the season and came out without one. Through their conversation, we learn that the date is April 14, 1961.

After bidding William a good night, Peter Corrigan steps out of the door of the Potomac Club. Then, a strange sensation comes over him. The camera blurs and comes back into focus as Corrigan checks his watch. The camera blurs again, and Corrigan reaches for his head.

After the second blur effect on Corrigan, the camera pans over to a light on the club’s stair landing. Before our eyes, the light changes from an electric bulb to a gas-powered flame.

When the camera pans back to Corrigan, his outfit has changed to a more Victorian style and his watch has disappeared off his wrist. He is confused by these changes, turns, and knocks on the door of the club he just exited. After a beat, Corrigan turns around and tells himself to go home. He slowly walks down the steps of the Potomac Club landing and notices other changes have occurred. On the street are horse-drawn wagons. All of the pedestrians are also dressed in Victorian garb, with the men wearing top hats. He rushes across the street and walks to his home, but the building now has a sign in front that says “Rooms to Let.” Finding the door locked, he knocks on the door. It is answered by a woman named Mrs. Landers. Corrigan looks around the inside of the house, thinking he has come to the wrong address.

Looking at the period decor in the building that was once his home, Corrigan starts to realize that something is greatly amiss. He asks Mrs. Landers if she has a room in which he can stay. She replies that she does, but only for acceptable boarders. She proceeds to ask Corrigan a series of questions, including inquiring if he is an army veteran. This comes as a bit of a non-sequitur to Corrigan, but he still replies in the affirmative. When he tells Mrs. Landers that he is an engineer, her demeanor completely changes at the thought of a “professional man” lodging in her home. She begins to offer Corrigan a room upstairs when they are interrupted by a couple coming down who greet Mrs. Landers. The elegantly dressed woman confirms that she and her husband, a soldier in a Union officer’s uniform, are having dinner at Willard’s and are then “off to the play.”

Mrs. Landers tells the couple to have a good time and to “applaud the President for me.” She then starts up the stairs with Corrigan in the lead. After a few steps, however, Corrigan abruptly turns and asks Mrs. Landers what she just said. Mrs. Landers is confused, so Corrigan heads back down the stairs and asks the officer to repeat what Mrs. Landers said about the President. The officer repeats the comment but is now suspicious. He asks Corrigan where his sympathies lie and Mrs. Landers inquires which army he was in. Corrigan begins to answer but pauses to take in the officer’s uniform. He eventually states he was in “The Army of the Republic, of course.” The soldier then rhetorically asks why Corrigan would make a big deal about applauding President Lincoln.

Finally, Corrigan appears to understand what has happened. He has somehow traveled back in time to a point during the Civil War. Corrigan starts putting it all together. This couple is going to a play tonight, and Abraham Lincoln will be there. Corrigan asks what theater and what play. The couple replies that the venue is Ford’s Theatre and the play is Our American Cousin. We can practically see Corrigan accessing his memory of historical events as he slowly realizes the significance of what he’s being told. He asks about the date, but he already knows the answer. He moves to exit the house, announcing, “It is April 14, 1865.”

Through some mysterious and unknown means Peter Corrigan has traveled back in time to the night of Lincoln’s assassination. Armed with the knowledge of what is to come, he is now on a mission to stop this national tragedy from occurring.

As the dramatic music swells, we cut to Baptist Alley behind Ford’s Theatre. Corrigan rushes past posted theater broadsides and makes his way to the nicely labeled “Stage Door.” Finding the door locked, he proceeds to bang on the door. He yells repeatedly to be let in and says, “The President is going to be shot tonight!”

The scene then dissolves into the interior of a metropolitan police station. Corrigan is led into the room by a patrolman and is stood before a police sergeant behind a desk. Corrigan is nursing a wound on his forehead. When the sergeant asks what Corrigan is in for, the patrolman recounts how he was trying to pound down the door at Ford’s Theatre while shouting nonsense about how the President was going to be shot. The patrolman states that the doorman at Ford’s Theatre had “popped him on the head” for his mania. Corrigan repeats to the sergeant that Lincoln is going to be shot tonight and that a man named Booth is going to do it. When the sergeant asks how Corrigan knows the President is going to be shot, Corrigan demurs, saying that if he told the sergeant how he knows, they would never believe him. Convinced that Corrigan is drunk, the police sergeant orders him to be locked up so that he can sleep it off. As he is dragged to a backroom that contains cells, Corrigan begs the police to put an extra guard on the President and yells out to everyone in the station that Lincoln will be shot by a man named John Wilkes Booth.

Right after Corrigan exits, an elegantly dressed man enters the station. He approaches the police sergeant and introduces himself as Jonathan Wellington. He inquires about Corrigan and suggests to the sergeant that the man may not be drunk but mentally ill. He asks the sergeant if Corrigan could be remanded into his custody as he would hate to see a possible war veteran placed in jail. Wellington assures the sergeant that he would be perfectly responsible for Corrigan and that he might be able to help him. The sergeant agrees and asks Corrigan to be sent out while Mr. Wellington waits outside.

Before the prisoner is released, one of the other patrolmen who had been present for the whole affair and heard Corrigan’s protestations, approaches the sergeant. He humbly suggests that perhaps something should be done in regard to Lincoln. The sergeant on duty dismisses the idea of sending police over to Ford’s Theatre on the word of some crackpot who likely lost his mind at Gettysburg.

The patrolman continues to advocate for sending a special guard to Ford’s Theatre, drawing the ire of the sergeant, who recounts to him that Lincoln has the whole federal army at his disposal and if they are satisfied with his protection, he should be too. The patrolman watches as Corrigan is brought out from the back room and exits out the door to a waiting Wellington.

The scene then changes to the interior of Mr. Wellington’s room, where Corrigan’s benefactor pours the time traveler a glass of wine. Corrigan drinks it down, thanking Wellington for the courtesy. Corrigan then asks Wellington about himself. Wellington states that he is in the government service, and as a young man in college, he dabbled in medicine of the mind. He asks Corrigan how he came to believe that the President was to be shot that night. Again, Corrigan demurs, saying that if he told him the truth of how he knows, Wellington would surely believe him to be insane. Corrigan begs Wellington to help him prevent the assassination by reiterating that a man named John Wilkes Booth will commit the act.

In the midst of their conversation, Corrigan becomes light-headed. Wellington notes that his head wound hasn’t been treated properly and that Corrigan had best cover it. Wellington hands over his handkerchief to Corrigan, who holds it against his head. Corrigan proceeds to sit and explains how faint and strange he suddenly feels. After a beat, Corrigan looks at the wine on the table and draws the conclusion that Wellington has drugged him. He gets to his feet and grabs Wellington by the collar, but in his weakened state, he is barely holding on.

Wellington tells Corrigan that he had to drug him for he was a very sick man who needed sleep and rest in order to regain his composure and reason. He lets Corrigan down slowly to the sofa below and encourages him to rest. Wellington announces he will be back soon. Corrigan, struggling against the effects of the sedative, begs Wellington to believe him that Lincoln will be shot. Before exiting the room, Wellington replies, “And that’s odd…because I’m beginning to believe you.”

With that, Mr. Wellington bids good night to Corrigan, telling him to rest well. Corrigan then passes out on the sofa, and Wellington makes his exit.

The next shot shows the stage of Ford’s Theatre. A lively audience is laughing and clapping along to the actors performing Our American Cousin. We then get a side view of the audience and stage, with the passageway leading up to the door of the President’s box in full view.

The Ford’s Theatre footage only lasts for a few seconds before we go return to Corrigan in Mr. Wellington’s room. Corrigan attempts to rouse himself off the sofa but only succeeds in falling to the floor near the fireplace. He pulls himself around the floor, attempting to get himself into a chair, but knocks it over instead. He flails and knocks away the empty glass on the table from which he had drank the drugged concoction. He crawls to the door and manages to get a hold of the knob, but it is locked, and he is unable to open the door. He calls for somebody to let him out before falling back down. Right before he passes out again, Corrigan states, “I know…I know…our President’s going to be assassinated.”

Sometime later, we hear a female voice on the other side of the door telling an officer that she has a key. The door unlocks, and in comes a chambermaid and the same patrolman who had suggested sending an extra guard to Ford’s Theatre. The patrolman wakes Corrigan and asks him what’s happened before admitting that, madman or not, Corrigan has convinced him that Lincoln is in danger. The patrolman recounts how he had been all over the city trying to get an extra guard for the President to no avail. Corrigan tells the patrolman to go to the theater himself if that’s what it takes.

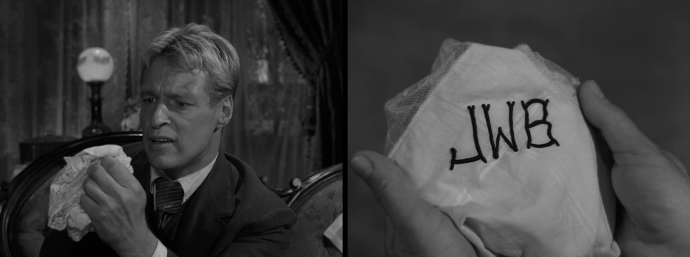

The patrolman helps Corrigan back to the sofa, and Corrigan recalls how Lincoln was shot from behind and the assassin jumped from the box to the stage and out into the wings. The patrolman says, “You’re telling me this as though it’s already happened.” Corrigan, desperate to stop the tragedy and no longer worried if this man will think him crazy, replies, “It has happened. It happened a hundred years ago, and I’m here to see that it doesn’t happen.” Corrigan then asks the chambermaid where Wellington is. The chambermaid replies that there is no one here by that name. Corrigan dismisses this remark and insists on the location of Wellington, the man who brought him there and lives in this room. The chambermaid replies again that no one named Wellington resides in this place. Exasperated, Corrigan raises his fist to shake it at the chambermaid when he sees he is still holding the handkerchief Wellington gave him. He opens up the handkerchief to reveal the stitched initials “JWB.”

The chambermaid confirms that Mr. John Wilkes Booth lives in this room and he was the man who brought Corrigan there. The realization comes to Corrigan that Booth lied about his name and had drugged him to prevent Corrigan from interfering with the assassination. With a bubbling anger, Corrigan gets to his feet and tells the patrolman that he has to get to Ford’s Theatre and stop it all.

However, just then, voices are heard from the street outside. Mournful voices proclaim that “The President’s been shot” and that “an actor shot Lincoln.” We cut to a gathered crowd mumbling over the news. Back inside the room, the occupants fall into a state of grief and shock. The chambermaid weeps into her hands. Corrigan collapses dejectedly back down onto the sofa. The patrolman removes his hat and mutters to himself, “You did know. Oh, my dear God,” before he and the chambermaid leave the room. A defeated Corrigan stands and walks to the window of the room. With righteous anger, he proclaims, “I tried to tell you. I tried to warn you. Why didn’t you listen?” He repeats his rhetorical cry, “Why didn’t you listen to me?” while banging on the window. Then suddenly, the shot shows Corrigan, back in his 1961 garb, banging on the door of the Potomac Club instead.

An older attendant opens the door of the club, and Corrigan rushes in. The attendant asks Corrigan if he has forgotten something, as he had only left a moment ago. Corrigan is confused by this remark and then asks the attendant for William, the attendant who had seen him out. The older attendant is perplexed and tells Corrigan that there are no attendants named William on duty at the club. Corrigan heads back into the drawing room, but not before taking a sad glance at the bust of Abraham Lincoln on the table.

The drawing room of the club is just like before, with Corrigan’s friends still seated around the card table. They make a remark about Corrigan being back so soon and invite him to join them, though his original seat is now occupied by a new fourth. Corrigan shakily says they had been talking about time travel, to which another member of the group, Jackson, says they are on a new tack now, “Money, and the best ways to acquire it.” Corrigan begins to address the group, noting that he has something important to say. However, before telling his friends about his trip into the past, he loses his nerve. Corrigan touches his head, implying that he now believes everything he has experienced has been in his mind. His friends ask him if he is alright, and Corrigan replies in the affirmative.

The group again invites Corrigan to pull up a chair and join the conversation about amassing a fortune. Jackson points out that William, the new fourth card player, has the best method. The camera focuses on William, and we see it is the same man who spilled coffee on Corrigan at the beginning of the episode, except now he is richly dressed and smoking a cigarette.

A gobsmacked Corrigan listens as this elegant and well-spoken William explains that the best way to amass a fortune is to inherit it. William discusses how his great-grandfather had been on the Washington police force on the night of Lincoln’s assassination and that he had gone around trying to warn people that something bad might occur. The details of how William’s great-grandfather knew something tragic might happen is not known, but the publicity surrounding his attempt to get extra security for Lincoln that night made him a known figure in Washington. He eventually became chief of police and a D.C. councilman before amassing a fortune in real estate. William’s wealth came to him in a beribboned box, courtesy of his notable great-grandfather.

Having previously written off his trip into the past as a hallucination of some sort, Corrigan is still shocked to find the much-changed William. He asks William questions like, “Didn’t you used to work here as an attendant? Didn’t you spill coffee on me?” These questions draw strange looks from all the men at the card table. William puts Corrigan in his place, telling Corrigan that he was a member of the club while Corrigan was still in prep school. He also snobbishly laughs off the notion that he would have ever been an attendant.

Now unsure of what he experienced, Corrigan tries to make sense of it all. He decides to return to the group’s prior conversation on time travel and announces that, “Some things can be changed. Others can’t.” The group returns to their card game as Corrigan walks away, still processing everything that has occurred. The men at the table remark how strangely Corrigan is acting and that he looks unwell. The camera stays on Corrigan as he pulls a handkerchief from his pocket to wipe his brow. Looking down at the handkerchief, Peter Corrigan sees the now familiar stitched initials, “JWB.”

As a shocked and confused Corrigan walks out of the drawing room with his historic handkerchief in hand, Rod Serling’s voice provides the closing narration.

“Mr. Peter Corrigan, lately returned from a place “back there.” A journey into time with highly questionable results. Proving, on one hand, that the threads of history are woven tightly and the skein of events cannot be undone. But, on the other hand, there are small fragments of the tapestry that can be altered. Tonight’s thesis to be taken as you will, in the Twilight Zone.”

The Players

Let’s take a look at the actors and actresses who make up this episode:

- Russell Johnson as Peter Corrigan

The protagonist of this piece is played by Russell Johnson. He was 35 years old when this episode was filmed. While not an army man like the character he portrayed, Johnson was a veteran, having served in the U.S. Air Force during WWII. A lifelong actor in both film and television, Johnson is best remembered for his role as “The Professor” Roy Hinkley in the syndicated TV show Gilligan’s Island. He also appeared in a number of Westerns and B-movies in his early career. Fellow fans of the show Mystery Science Theater 3000 will likely recognize Johnson for his supporting role in the 1955 film This Island Earth, which was lampooned in the 1996 movie version of MST3K. “Back There” was Johnson’s second of two appearances on The Twilight Zone. On March 31, 1960, he appeared in the first season episode entitled “Execution.” In that show, Johnson played a professor named George Manion, who had invented a time machine. He reaches back in time to 1880 and plucks out a man from the past and brings him to the present. Unbeknownst to the professor, the man from the past is a convicted murderer who was pulled through time just as he was to be executed for his crime. With fresh rope burns on his neck from the hangman’s noose that hadn’t quite finished the job, the murderer from the past eventually attacks and kills Johnson’s character before rushing out into a very modern and confusing world. In an interview he gave later in his life, Johnson fondly recalled his time in the “Back There”:

“That was a terrific story. It was interesting and it was a unique take on the time travel theme. I really enjoyed filming it, too. It was a period piece and I’m not a fellow who enjoys putting on false hair and beards and all of that, but thank God I didn’t have to do that in this one. This was just costumes, and costumes are no hassle at all… I’m grateful for having had the opportunity to be in two Twilight Zones. I’m very proud of them and love to see them every time they have a marathon.”

Russell Johnson died in 2014 at the age of 89.

- John Lasell as Jonathan Wellington/John Wilkes Booth

Fellow Lincoln assassination researcher Richard Sloan once interviewed John Lasell regarding his role in “Back There.” The actor told Richard that he was incredibly nervous filming the show, as The Twilight Zone was his first film role. His credits seem to bear this out as only a likely live production for the Armstrong Circle Theatre in March of 1960 predates the recording of “Back There.” Lasell had a background in live theater and was 32 during the filming of this episode. He worked pretty consistently from the 1960s through the mid-1970s in supporting television roles. His only recurring role was that of vampire hunter Dr. Peter Guthrie in the cult soap opera series Dark Shadows from 1966 – 1971. From 1964 to 1974, Lasell was married to actress Patricia Smith, another Twilight Zone performer. Smith appeared in the second season episode “Long Distance Call,” which was filmed three months after “Back There.” In that episode, a young boy, played by child actor Billy Mumy, is able to communicate with his dead grandmother over a toy telephone, and the grandmother tries to convince the boy to join her in death. Smith plays the mother of Mumy’s character in one of the most audacious episodes of the series. John Lasell’s last acting credit was in 1985. Like his co-star, Lasell had good memories of being on The Twilight Zone, telling an interviewer:

“I came out from New York in 1960 or so and ‘Back There’ was my first piece of film. Not the first to air, but the first one I shot out in California. I was always very fond of it. I was lucky to get the part and they were very nice people there, they really knew how to work with a young actor. But I can’t stand to look at it today. I was so uptight in my performance!”

The main catalyst of this post was the news that John Lasell just passed away on Oct. 4, 2024, at the age of 95.

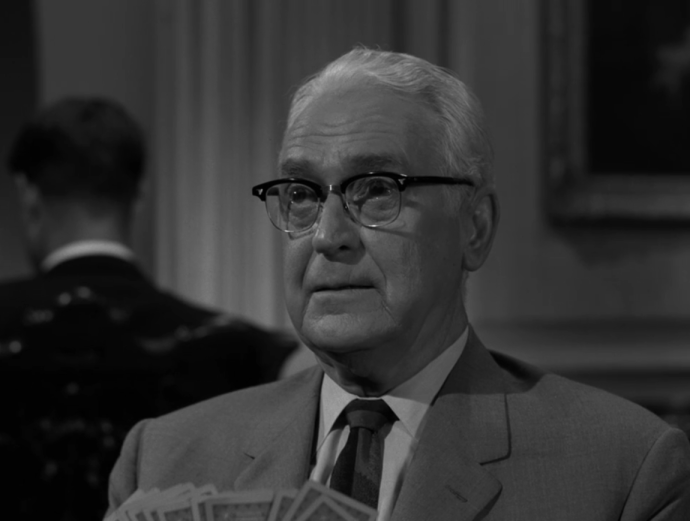

- Bartlett Robinson as William

Bartlett Robinson started his career as a stage and radio performer. He was the first person to voice the character of lawyer Perry Mason when the radio series debuted in 1943. His first screen credit occurred in 1949 during the first season of an anthology series sponsored by the Ford Motor Company called, somewhat ironically, the “Ford Theatre.” Robinson worked consistently in television for the rest of his career, often playing characters of authority. He made two appearances on The Twilight Zone. His second appearance occurs in one of the most famous episodes of the series, “To Serve Man.” In that episode, Robinson plays the army Colonel who tasks the main character with deciphering the book that the alien Kanamits have left behind. One of Robinson’s final roles was in the 1974 miniseries Lincoln, which starred Hal Holbrook as the 16th President. Robinson appears briefly as a “bewhiskered Senator.” Bartlett Robinson died in 1986 at the age of 73.

- Paul Hartman as the Police Sergeant

The child of two vaudeville actors, Paul Hartman took to the stage at an early age. He was a notable dancer and comedian who performed on Broadway with his wife, Grace Hartman, and had a few early roles in movie musicals. In 1948, he and Grace both won Best Actor and Actress Tony Awards for their performances in their own musical revue show “Angel in the Wings.” In the 1950s, Hartman exchanged the hectic life of live theater for television. He moved to Los Angeles and made a living as a character actor. He is most likely remembered for his regular role of Emmett Clark, the fix-it shop owner on the final season of The Andy Griffith Show and its spin-off, Mayberry, RFD. Hartman died in 1973 at the age of 69.

- James Lydon as the Patrolman

James was known as “Jimmy” Lydon from his early days playing child and adolescent characters. This included a series of nine films from 1941 – 1944 where a late teenage Lydon played the lead role of Henry Aldrich, a popular radio character. The following decade was filled with many young man roles for Lydon. By the 1960s, Lydon continued to act while also working in television production. His last acting credits were a handful of guest spots in the 1980s. James Lydon died in 2022 at the age of 98.

- Jean Inness as Mrs. Landers

From 1920 until 1942, Jean Inness was exclusively a stage actress. She was a member of multiple touring companies that traveled around the country. In 1942, at the age of 41, Inness made her first film appearance. In 1952, she started a television career in which she played supporting roles like Mrs. Landers in “Back There.” Her only recurring role was that of Nurse Beatrice Fain in the medical drama Dr. Kildare, which aired from 1961 to 1966. Inness appeared in 37 of the show’s 191 episodes. Jean Inness died in 1978 at the age of 78.

- Lew Brown as the Lieutenant

Lew Brown was an Oklahoma native who served as a Marine corporal in WWII. After the war, he taught English literature in Missouri before moving to New York to pursue an acting career on the stage. He eventually relocated to California and made his television debut in 1959 as a soldier in an episode of Playhouse 90. “Back There” was Brown’s first of three appearances on The Twilight Zone. He had a small role as a fireman in “Long Distance Call,” the same episode that featured John Lasell’s future wife, Patricia Smith. He also appeared in the fifth season episode, “The 7th is Made Up of Phantoms,” as a sergeant in General Custer’s ill-fated cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Brown also appeared in an episode of Rod Serling’s follow-up series, The Night Gallery, in 1972. A common character actor from the 1960s onward, his only recurring role came in 1984-1985 when he appeared in 40 episodes of the soap opera Days of Our Lives as Shawn Brady. Brown died in 2014 at the age of 89.

- Carol Rossen as the Lieutenant’s Wife

Carol Eve Rossen is the daughter of Hollywood screenwriter and director Robert Rossen. She made her screen debut in 1960, the same year “Back There” was filmed. Less than a year after filming The Twilight Zone, Rossen reunited with her costar, Jean Inness, when both women appeared in the first episode of Dr. Kildare. In 1966, Rossen married actor Hal Holbrook, and the couple was still married when Holbrook appeared in the Lincoln miniseries with Barlett Robinson. Rossen and Holbrook divorced in 1983. Rossen made her film debut in 1969, and in 1975, she appeared in the original The Stepford Wives movie. Tragedy struck Rossen on Valentine’s Day in 1984. While taking a morning walk through Will Rogers State Park in Los Angeles, Rossen said good morning to a random man jogging past her down a trail. Not long after, that same man turned around, ran back up to Rossen, and violently attacked her with a 3-foot-long hammer. She fought back against her attacker as he swung at her with his hammer. Rossen suffered a violent blow to the top of her head and was knocked down into a ditch. Rossen played dead, and her attacker fled. She miraculously recovered from the incident and wrote a book about her experiences in 1988. Sadly, Rossen’s attacker has never been identified. Since that time, Rossen has only had two other acting credits, both in the 1990s. In addition to her book about her attack, she has also written a biography about her father, which was published in 2019. Rossen is the last surviving cast member of “Back There,” having celebrated her 87th birthday in 2024.

Update: I reached out to Ms. Rossen through her website, asking about any memories she had in filming this episode. She replied with:

“Twilight Zone was one of the first shows I did in California. Truly, the only thing I remember about the very brief shoot was almost tripping on a camera cable as I walked down the staircase. A somewhat haphazard directorial attitude when working with young actors. There was no discussion of the Lincoln assassination or its historical context.”

- Raymond Bailey as Millard

It’s fitting that the most vocal of Corrigan’s rich friends at the posh Potomac Club, Millard, was portrayed by Raymond Bailey, as his most famous role was that of the miserly banker Milburn Drysdale from The Beverley Hillbillies. Bailey portrayed Mr. Drysdale in 248 episodes of the show from 1962 – 1971. Bailey had made his screen debut in small uncredited film roles back in 1939. During WWII, he served in the United States Merchant Marines. His first television role occurred in 1952. “Back There” was Bailey’s second of three appearances in The Twilight Zone. He had earlier appeared in season one’s “Escape Clause,” playing the abused doctor of the hypochondriac main character. He later returned in season five’s “From Agnes – With Love,” playing the supervisor of the master programmer who takes love advice from a computer. In 1956, Bailey played the role of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in the live television production “The Day Lincoln Was Shot” on the anthology series Ford Star Jubilee (my thanks to Richard Sloan for cluing me in on this fact). Raymond Bailey began experiencing memory issues near the end of The Beverly Hillbillies and only appeared twice more on screen after the series ended. He died on the anniversary of Lincoln’s death, April 15, 1980, at the age of 75.

- Raymond Greenleaf as Jackson

Raymond Greenleaf was born in 1892, the oldest credited cast member in “Back There.” He had been a traveling stage actor since the early 1920s. He performed on Broadway in the 1940s before making his film debut in 1948. In 1949, he appeared in the movie All the King’s Men, which was written, directed, and produced by Robert Rossen, the father of Greenleaf’s costar in “Back There,” Carol Rossen. By 1952, he had started taking on television roles, and these came to outnumber his film credits as time went on. Greenleaf was often cast in the roles of judges, doctors, and sheriffs. He died in 1963 at the age of 71.

- Nora Marlowe as the Chambermaid

Nora Marlowe’s first screen credit dates to 1953. A hard-working character actress in television and film, she has over 130 credits to her name. She appeared in two episodes of The Twilight Zone. Her second is in the season five episode, “Night Call,” where she plays Margaret Phillips, a caretaker for an elderly woman who begins receiving unsettling and otherworldly phone calls in the middle of the night. That episode was originally scheduled to air on November 22, 1963, but all regular programming was canceled on that date due to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. “Night Call” eventually aired in February of 1964. Marlowe is likely best known for her recurring role as the boardinghouse owner, Mrs. Flossie Brimmer, on The Waltons. Her 27 episodes of The Waltons marked her final acting credits. Nora Marlowe died between season 6 and season 7 of the show on December 31, 1977, at the age of 62.

- James Gavin as the Arresting Patrolman

James Gavin was a TV character actor working consistently from the mid-1950s until about 1970. Much of Gavin’s work was in Western shows, but he did have a few film credits to his name. His last screen credit was in 1975. Gavin died in 2008 at the age of 88.

- John Eldredge as Whitaker

Like many of his costars, John Eldredge got his start as a stage actor in New York. He appeared on Broadway and secured a contract with Warner Brothers. He made his first film appearance in 1934. He was a prolific character actor in film, appearing in over 80 movies between 1934 and 1950. In 1950, he took his first television role and continued to split his time pretty evenly between TV and film roles in the years that followed. His only main role was on a short-lived television show called Meet Corliss Archer, which aired for a single season in 1954. Eldredge appeared in all 39 episodes of the series as the father of the titular teenager. John Eldredge died at the age of 57 in 1961, just eight months after the airing of “Back There.”

- Pat O’Malley as the Attendant

Born in 1900, Pat O’Malley was the most prolific actor in “Back There.” He started his career in entertainment as a child vaudeville performer before moving into film. In 1914, he made his first screen appearance in the silent film The Best Man. The silent era was the most successful for O’Malley, as he appeared in over 90 films over a 15-year period. During this time, he often played lead roles. When talking pictures came in the late 1920s, O’Malley’s leading roles came to an end, but he continued to be a prolific character actor in supporting and often uncredited roles. He made his first appearance on television in 1950 and evenly split his time between film and TV for the next five years. Starting in 1956, he worked exclusively in television. “Back There” was O’Malley’s second of three appearances on The Twilight Zone. He earlier appeared in the nostalgic episode “Walking Distance” from season one, where he played the slumbering Mr. Wilson in the stockroom of the soda shop revisited by the main character. He returned in another nostalgic episode, “Static,” which is one of the videotaped episodes in season two. In that episode, O’Malley played Mr. Llewelyn, one of the older residents who witnessed Dean Jagger’s character get sentimental over an old radio that only he could hear. O’Malley made his last appearance on screen in an uncredited film role in 1962. He died in 1966 at the age of 75. Pat O’Malley more than doubles any of his “Back There” co-stars’ screen appearances, racking up just under 450 screen credits during his nearly 50-year career.

Production Facts

The Script

Out of the 156 episodes of The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling wrote the scripts for 92 of them. “Back There” was one of these Serling-penned stories. In his book, The Twilight Zone: Unlocking the Door to a Television Classic, media historian Martin Grams, Jr., writes that Serling had originally intended this to be an hour-long teleplay. Serling offered the hourlong version of this script, then called “Afterwards,” to the Armstrong Circle Theatre, but they decided against buying it. Serling attempted to convince the sponsors of The Twilight Zone to expand the show to an hour, but the second season was already over budget, which led to some of the shows being recorded on videotape instead of film as a cost-saving measure. Serling was forced to cut his script down to 23 minutes, and he retitled the show “Back There.” Serling eventually got his wish for an hour-long timeslot during the fourth season of The Twilight Zone. One of his scripts for that season, “No Time Like the Past,” also deals with the concept of traveling back in time in an attempt to change history. That episode even has a plot point about the assassination of a president, but it is about President Garfield, not Lincoln.

In volume 10 of the series, As Timeless as Infinity: The Complete Twilight Zone Scripts of Rod Serling, edited by Tony Albarella, a working script for “Back There” dated July 28, 1960, can be found. This script differs somewhat from the final shooting version of the script that was finalized on September 14. Some of the changes in the script are small, like “The Potomac Club” originally being called “The Washington Club” and the fact that the script has Corrigan gaining a hat when he appears in the past. There are also a few extra lines here and there, and altered versions of other lines. The largest change from the July script and what was eventually shot was the introductory scene between Corrigan and William. In this earlier version, William does not spill any coffee on Corrigan. Instead, their interaction goes like this:

As Corrigan heads toward the front door

WILLIAM

(going by)

Good night, Mr. Corrigan.

CORRIGAN

Good night, William.

(then he looks at the elderly man a little more closely)

Everything all right with you, William? Looks like you’ve lost some weight.

WILLIAM

(with a deference built of a forty year habit pattern)

Just the usual worries, sir. The stars and my salary are fixed – it’s the cost of living that goes up.

Corrigan smiles, reaches into his pocket, starts to hand him a bill.

WILLIAM

Oh no, sir, I couldn’t-

Corrigan forces it into his hand.

CORRIGAN

Yes, you can, William. Bless you and say hello to your wife for me.

WILLIAM

Thank you so much, sir.

(a pause)

Did you have a coat with you…

From there, the scene continues like the show, with Corrigan saying he felt spring in the air and William telling him the date is April 14th.

The Director

According to Martin Grams, Jr., rehearsal for “Back There” occurred on September 16 and 19, 1960, and filming took place on September 20, 21, and 22nd.

“Back There” was directed by David Orrick McDearmon. He had been a television actor in the 1950s before making the switch to directing. This was McDearmon’s third and final directorial outing for The Twilight Zone. Earlier in season two, he directed “A Thing About Machines” about a recluse narcissist tormented by the mechanical objects in his house. McDearmon’s first directing job in The Twilight Zone was season one’s “Execution.” That is the same episode that featured Russell Johnson as the professor who brings a murderer from the past into the present. He would direct Russell Johnson twice more on Gilligan’s Island in 1967. David Orrick McDearmon died in 1979 at the age of 65.

Filming Location

When not out at a field location like Death Valley, The Twilight Zone was filmed at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios. While the interior scenes could have been filmed at any number of MGM sound stages, I decided to take a crack at trying to pin down the location of the exterior scenes in “Back There.” These scenes consist of Corrigan walking from the Potomac Club to his home, turned 1865 boardinghouse. The city landscape of the scene led me to Lot 2 of MGM Studios in Culver City, CA.

One of the sections of Lot 2 was known as the “New York City Streets” section. This can be seen in the top right area of the map above. This section was used in a number of films and TV shows to represent any metropolitan city. While different streets in this section usually represented different periods of time, all of the existing exteriors could also be easily redressed to fit a desired time frame.

In the episode, the door of The Potomac Club building is accessed via a decorative landing with two sets of stairs running up either side. After walking down these steps onto the street level, Corrigan observes the horse-drawn carriages and the clothing of the passersby before running across the street. The words “Mantel Clocks” can be seen on the top of the building across the street.

In the next exterior shot, Corrigan walks on a sidewalk in front of some buildings to the front of what he expects is his home, but in 1865, is a boardinghouse instead. At the beginning of the shot, we can still see the steps of the Potomac Club in the background, showing that this was shot on the same street (and that Corrigan lives extremely close to the club).

This street layout perfectly matches Wimpole Street on the MGM Lot 2 map.

During my search, I came across an interesting website from a former “Phantom of the Backlot” – a person who used to trespass and explore studio backlots back in their heyday. In a post where the Phantom recalled playing baseball in this section of the lot, they included an image of Wimpole Street. I’ve highlighted the matching features.

From this photographic evidence, we can conclude that these scenes were filmed on Wimpole Street.

The only other exterior shot in the episode is when Corrigan rushes to the back of Ford’s Theatre and starts pounding on the door to be let in. Unfortunately, there isn’t enough detail in this shot for me to determine where it was filmed. As can be seen from the map, however, there were plenty of small alleyways and nooks where such a scene could have been shot on Lot 2.

Editing

In addition to having to winnow the original script down to fit the half-hour timeslot, even more cuts were made to “Back There” during the editing process. In the scene where Corrigan first interacts with Mrs. Landers at the boardinghouse, a jump cut can be seen between Mrs. Landers’ question, “Whom do you wish to see?” and Corrigan’s next line, “I used to live here.”

According to the script, after Mrs. Landers’ question, Corrigan replies with “I’m just wondering if…” before trailing off. Then Mrs. Landers repeats her question, “Whom do you wish to see, young man?” which is where the episode picks back up. Interestingly, according to Rod Serling’s script, all of this conversation is supposed to be taking place with Corrigan standing outside the door on the stoop. Mrs. Landers does not allow him into the house until after he tells her he is an army veteran. Obviously, filming constraints led the director to move this dialogue inside.

Another more significant edit occurred in the moments after Corrigan appeared in the past. After checking out his change of clothes, Corrigan turns to bang on the door of the club. In the episode, a subtle cut is made here, and then Corrigan turns around and mumbles about going home.

However, this edit actually removed an entire character from the show. According to the script, when Corrigan bangs on the door in the past, it is opened by a club attendant in 1865. The two men then have the following conversation:

ATTENDANT

Who is it? What do you want?

CORRIGAN

I left something in there.

He starts to push his way in and the attendant partially closes the door on him.

ATTENDANT

Now here you – the Club is closed this evening.

CORRIGAN

The devil it is. I just left here a minute ago.

ATTENDANT

(peers at him)

You did what? You drunk, young man? That it? You’re drunk, huh?

CORRIGAN

I am not drunk. I want to see Mr. Jackson or Mr. Whittaker, or William. Let me talk to William. Where is he now?

ATTENDANT

Who?

CORRIGAN

William. What’s the matter with you? Where did you come from?

(then he looks down at his clothes)

What’s the idea of this –

(He looks up. The door has been shut. He pounds on it again, shouting)

Hey! Open up!

ATTENDANT (voice from inside)

You best get away from here or I’ll call the police. Go on. Get out of here.

This scene was filmed but cut during the editing process. The 1865 attendant was portrayed by actor Fred Kruger. A television character actor, Kruger had also appeared in the first season Twilight Zone episode, “What You Need.” In that show, he played the “Man on the Street,” who received a comb from the elderly peddler who foresaw he would be getting his picture taken.

His cut work in “Back There” would be among Fred Kruger’s final roles as he died on December 5, 1961, at the age of 48.

Borrowed Footage

There are four shots in “Back There” that utilize footage from another production. These consist of two shots showing the interior of Ford’s Theatre during Our American Cousin and two shots of a crowd ostensibly on the street outside Corrigan’s window announcing the news that the President has been shot.

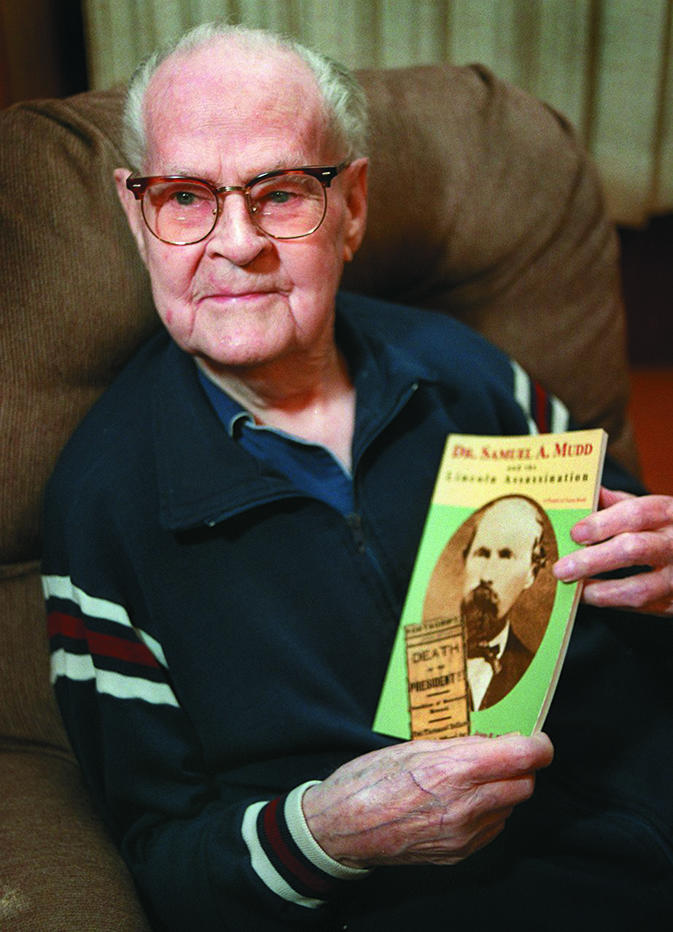

I knew that these scenes had to have come from somewhere else, so I reached out to Richard Sloan, an expert on Lincoln in film and TV, and asked him if they looked familiar. He quickly recognized that Frank McGlynn, Sr., a regular Lincoln actor, portrayed the Lincoln in the box. Richard determined that the Ford’s Theatre scenes came from the 1936 film The Prisoner of Shark Island, which tells a largely fictional tale about the arrest and imprisonment of Dr. Samuel Mudd. With this lead, I was able to determine that the crowd scenes also come from The Prisoner of Shark Island and depict the crowd that arrives at the White House at the beginning of the film to hear McGlynn’s Lincoln speak about the surrender of Robert E. Lee.

Interestingly, all of the footage from The Prisoner of Shark Island used in “Back There” is supplemental footage that wasn’t used in the film. While the film has similar shots using the same angles and actors, the footage used in The Twilight Zone is slightly different, showing that the production acquired unused material, likely from the film’s own cutting room floor.

Richard emailed Martin Grams, Jr., asking about this, noting that The Prisoner of Shark Island was released almost 25 years prior to the filming of “Back There.” Grams replied that Twilight Zone producer Buck Houghton likely contacted 20th Century Fox looking for Lincoln assassination footage, and the studio licensed the use of stock footage from the movie.

The Score

This episode features a custom musical score that was written and conducted by noted composer Jerry Goldsmith. The different tracks of this episode bear titles such as “The Club,” “Return to the Past,” “Ford’s Theatre,” “Mr. Wellington,” “The Wine,” “The Assassination,” and “Old William,” to name a few. As budgetary and time constraints prevented each episode of The Twilight Zone from having its own custom score, the tracks from “Back There” became part of the studio’s stock music collection and were often reused. In all, music from “Back There” can be heard in ten other episodes of the show*. Most notably, “Return to the Past” is heard when the Kanamits make their first appearance to the U.N. in the classic episode “To Serve Man,” and “Ford’s Theatre” is played at the climatic moment of “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” when William Shatner’s character opens the door of the plane to shot at the gremlin. I’ve created a short video highlighting these examples:

The Trailer

In addition to his normal opening and closing narrations, Rod Serling also appeared at the very end of each episode in a short trailer highlighting next week’s episode. These casual trailers are not included in reruns or on streaming services. However, the episode trailers do appear on some of the physical releases of the series. Here is the trailer for “Back There,” which appeared at the end of the prior episode, “Dust:”

The total cost for the production of “Back There” was $47,090.82, with the cast pay consisting of $4,518.46. Despite Russell Johnson’s character giving the date as April 14, 1961, “Back There” originally aired on January 13, 1961. It was the thirteenth episode of The Twilight Zone‘s second season.

Trivia (historical and otherwise):

- A healthy chunk of the show occurs at The Potomac Club in Washington, D.C. The sign outside of the club states that it was established in 1858. There actually were a few Potomac Clubs that existed in D.C. during the pre-Civil War years. In 1854, one Potomac Club was founded by members of the local Vigilant Fire Company and acted as a fundraising arm for the fire department. In 1857, the Potomac Fishing Club was established and hosted its first-ever picnic. In 1858, the Potomac-Side Naturalists’ Club was founded, devoted to the study of natural history. Unlike the Potomac Club in the show, however, none of these organizations had fancy clubhouses of their own. The Potomac Club in “Back There” is a purely fictional gentlemen’s club, but not unlike the club Edwin Booth later founded in New York City, The Players.

- When the camera pans over to Rod Serling as he gives the opening narration, he is seen seated in an armchair and reading a newspaper. The newspaper he is reading is “The Daily Journal,” a fictional prop newspaper. We’re all familiar with the TV and movie trope of a shot of a newspaper with a headline about a plot point in the drama. While this main story is often unique to a specific production, the same secondary articles can be found over and over again across many movies and shows. In Serling’s newspaper, some of the article titles include “Three Persons Die in Crash,” “Northside Hospital Building Fund Nears Goal with State Support,” “Bids Given on Bridge Project,” “Move to Ban Office Mergers is Begun,” “Fire Destroys State Aresnal, “$60,000 Damage in Gigantic Eastside Warehouse Fire,” and “Firemen, 18, Hurt as Engine Upsets.” If you image search any of these article titles, you will find their appearance not only in other Twilight Zone episodes but in many other shows and movies. For example, fictional newspapers containing the story “Northside Hospital Building Fund Nears Goal with State Support” can be found in movies like The Day the Earth Stood Still, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and The Godfather.

- The bust of Abraham Lincoln that is displayed at the Potomac Club was sculpted by Max Bachmann, a German-born sculptor who resided in New York. Bachmann lived from 1862 to 1921. As early as 1901, he sculpted two busts of Lincoln, identical except that one featured the bearded President and the other was clean-shaven. These busts were distributed by P.P. Caproni and Brother and became very popular. Bachmann’s Lincoln busts were credited as being the most life-like recreations of the President in sculpture. In 1911, Caproni started offering full Lincoln statues, the bodies of which were based on Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ standing Lincoln statue, but with Bachmann’s busts used as the heads. I’m indebted to fellow researcher Scott Schroeder for helping me identify this Lincoln bust. Scott and Dave Wiegers have been working on a great map of known Lincoln statues and monuments that you can check out by clicking here.

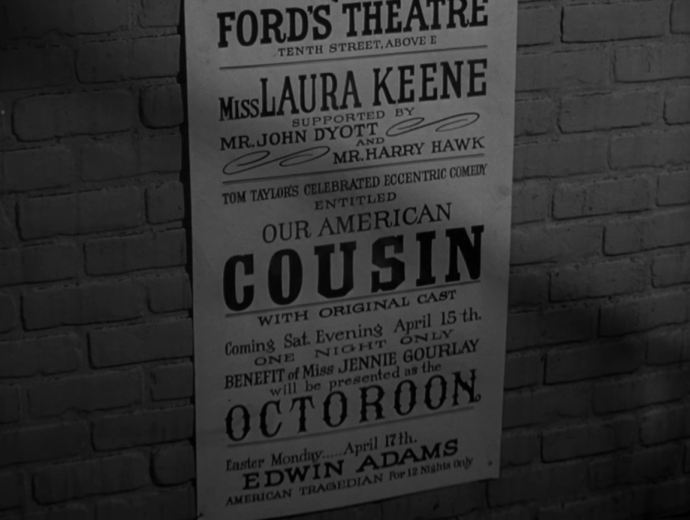

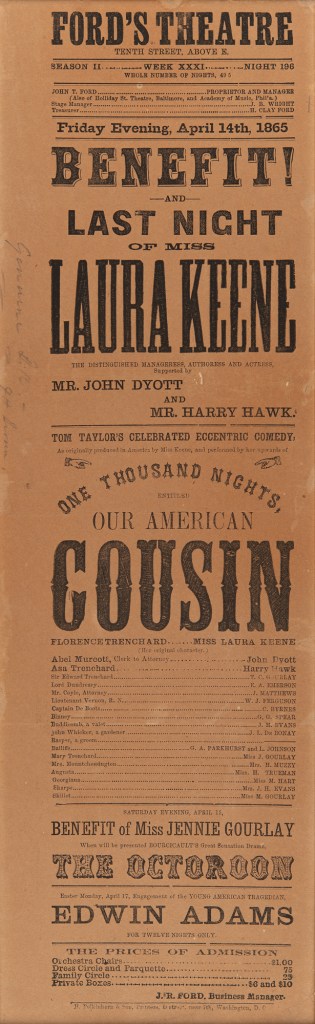

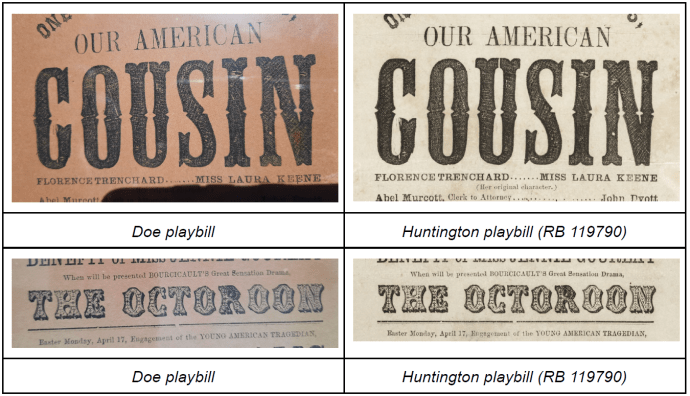

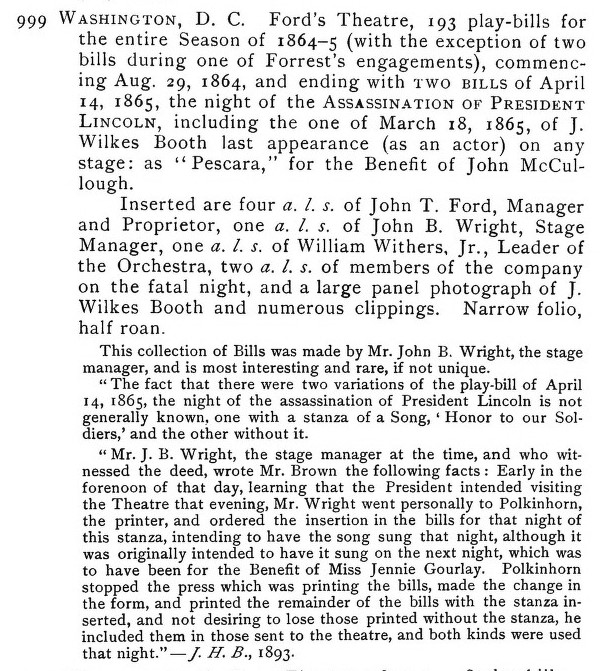

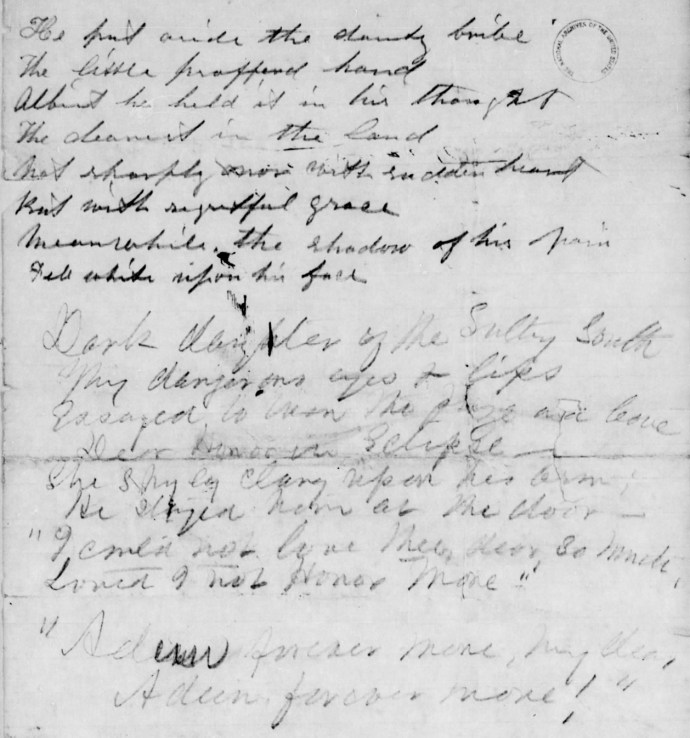

- In the scene where Corrigan is shown running up Baptist Alley and pounding on the stage door of Ford’s Theatre, two large broadsides are shown. One of them is a mock-up of a broadside announcing that night’s performance of Our American Cousin. It is similar in style to a modified Ford’s Theatre playbill and, as far as props go, is well done. The other broadside, only seen as Corrigan runs up, is not a duplicate of the Our American Cousin poster but an advertisement for the next night’s show of The Octoroon. After the assassination of Lincoln, this performance did not go on, but the Ford brothers had commissioned the making of a broadside announcing the performance. In a picture taken of Ford’s Theatre draped in mourning shortly after the assassination, the broadside for The Octoroon can be seen posted on the side of the street near the theater.

“Back There” did a decent job of recreating this broadside and gets bonus points for including such an obscure reference in a shot that lasts just seconds.

- There are a few notable decorations in the police station where Corrigan is brought after his unsuccessful attempt to enter the back door of Ford’s Theatre.

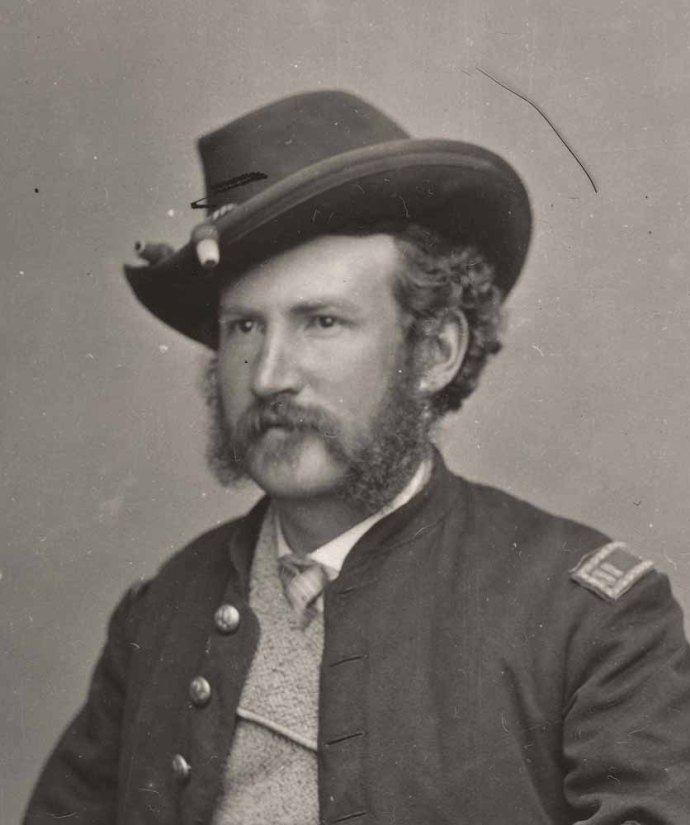

Hanging on the back wall of the police station, near the door where both Corrigan and Mr. Wellington make their entrances and exits, we can see a lithograph of General Grant and President Lincoln. The specific print shown is called “The Preservers of Our Union” and was published by Kimmel & Forester in 1865.

- Behind the police sergeant at the front of the room, there is an American flag on a staff and two portraits. While the flag is not completely unfurled, the visible star pattern looks like it might have been the correct 35-star flag that existed between July 1863 and July 1865. You have to respect the prop department for going out of their way to find a period flag, even though very little of it is seen.

- One of the portraits hanging near the flag is a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s Athenaeum Portrait of George Washington. The original painting was done from life in 1796, but was left unfinished by Stuart.

Stuart used the Athenaeum Portrait as his model for many subsequent paintings of Washington made after the President died in 1799. A print of one of Stuart’s paintings was framed and used to decorate the outside of the box at Ford’s Theatre, which was occupied by President Lincoln on the night of his assassination. The image below shows that portrait of Washington, which was knocked off the box when John Wilkes Booth made his leap to the stage.

- The image to the left of the police sergeant’s podium is a large, oval portrait of Abraham Lincoln. This appears to be a painting based on Francis Bicknell Carpenter’s 1864 drawing of Lincoln, which was published in 1866 by engraver Frederick Halpin.

Carpenter lived in the White House for six months in 1864. During this time, he was engaged in painting his most famous work, “First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln.”

- During the police station scenes, one of the cameras used for some of the close-up shots suffered from a “hair in the gate.” This is when an actual hair or a sliver of broken-off film gets trapped in the camera’s film gate. This hair blocks part of the film, preventing it from being exposed. Since these hairs couldn’t be seen through the viewfinder, a hair in the gate could ruin a shot and might not be noticed until editing. Sets often stopped to “check the gate” after each shot to ensure that the footage was usable since it was extremely difficult to edit out such hairs in the pre-digital age. In the close-ups of the police sergeant and then of the patrolman who suggests putting extra guards on Lincoln, a small hair can be seen in the top right corner of these shots. Evidently, someone didn’t “check the gate” during these shots.

- In his room, Mr. Wellington relates to Corrigan that he dabbled in “medicine of the mind.” Corrigan replies with the word “psychiatrist,” but Mr. Wellington says he doesn’t know that term. This is a correct statement. The term psychiatry didn’t really make its appearance in English until around 1846, and it took far longer than that before the word psychiatrist came to be used to refer to a practitioner. It will be remembered that most psychiatric disorders were given the broad description of “insanity” in those days, with affected individuals being sent to insane asylums. Even if Mr. Wellington had truly dabbled in the “medicine of the mind,” the term psychiatry and psychiatrist would have been completely foreign to him in 1865.

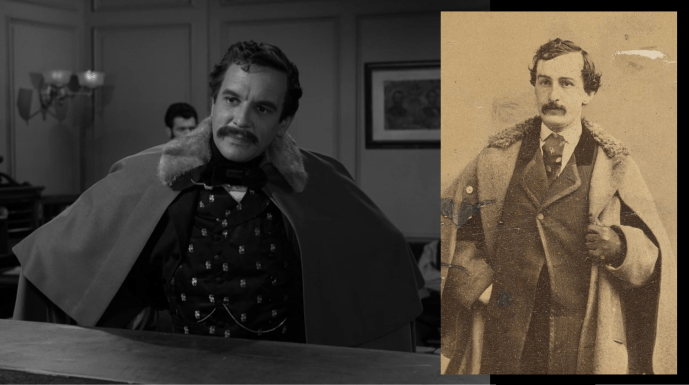

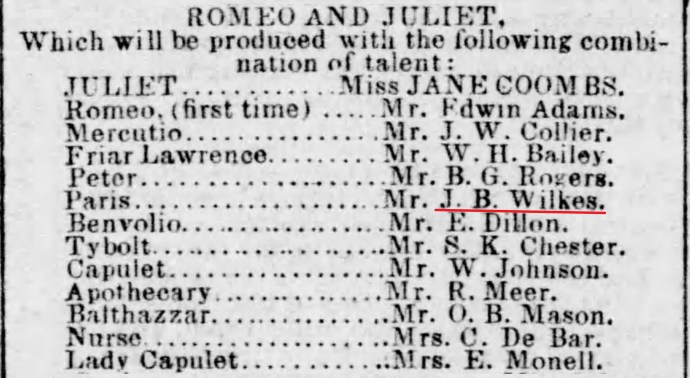

- Wellington/Booth recalls his own days “as a young man” in college. Like in many other productions featuring the Lincoln assassination, John Wilkes Booth is portrayed in “Back There” as a far older man than he was. Booth was only 26 years old when he killed the President and had never gone to college. It’s even more humorous that Booth refers to Corrigan as “his young friend” since Russell Johnson was three years older than the 32-year-old John Lasell, who played Booth. While Lasell may have looked a little on the older side, his portrayal is a marked improvement over Francis McDonald’s appearance as JWB in The Prisoner of Shark Island:

McDonald was around 45 when he played the assassin, but looked far older than his years.

- “Back There” did a great job of costuming Lasell as John Wilkes Booth. From the moment he arrives at the police station, it is clear that he is a man of elegance. Even the otherwise curt police sergeant speaks to him reverently because of his dress and appearance of standing. The long coat that “Wellington” wears is a decent copy of a similar fur-collared coat that Booth wears in multiple photographs.

- The decor in Wellington’s room also matches the aesthetic of wealth. While Booth may not have been considered wealthy, especially after spending a great deal of money to further his plot against Lincoln, he would have undoubtedly wanted to portray the illusion of wealth and status. His room is filled with images, artwork, vases, and sculptures, not unlike the decor in the posh Potomac Club. The only decorative items I’ve been able to identify in this room are two silhouette images hanging near the door of the room. They are both lithographs duplicating the work of William Henry Brown, a well-known silhouette artist who lived from 1808 to 1883. Extremely skilled in the craft of capturing a person’s profile, Brown often cut his silhouettes from life free-hand in a matter of minutes. Numerous notable persons had their silhouettes cut by Brown.

The rightmost lithograph, only partially visible when Wellington starts to exit, depicts President John Quincy Adams. The left lithograph, which turns up in multiple shots in the room, depicts another president: John Tyler. While I don’t know John Wilkes Booth’s view on John Quincy Adams, the actor would have likely been a fan of President Tyler due to his support of the South’s secession. The former President was actually elected as a Representative to the Confederacy’s House of Representatives but died in January of 1862 before he could take his seat. Jefferson Davis had Tyler buried in Virginia with his coffin draped in the Confederate flag. Due to his betrayal of the country he served as President, Tyler’s is the only Presidential death that was not officially recognized or mourned in Washington.

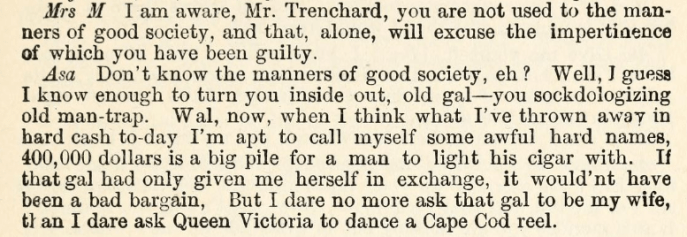

- In the room, when Corrigan asks for the time, Wellington looks at his watch and states, “Half past seven. [The] play doesn’t begin for another three-quarters of an hour.” According to Thomas Bogar’s wonderful book, Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination, the normal curtain time for performances at Ford’s Theatre was 7:45 p.m. However, on the night of April 14th, the starting time for Our American Cousin was delayed as the house waited for the arrival of the President and his party. Musical director William Withers led his orchestra in the playing of several patriotic songs to pass the time. However, half an hour passed, and the President’s party still had not arrived. John B. Wright, the stage manager of Ford’s, decided they had waited long enough, and so the play began without their celebrated guests present. While “Back There” actually gives the correct start time of Our American Cousin as 8:15, Wellington/Booth would not have known about the delay if he were still in his hotel room at 7:30.

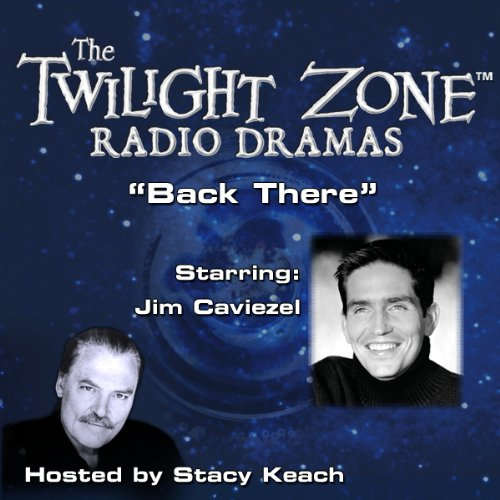

Other Adaptations

From 2002 – 2012, classic episodes of The Twilight Zone were adapted as audio dramas and played over syndicated radio. In these Twilight Zone Radio Dramas, a guest celebrity actor would come in and take on the main role of an episode while the rest of the roles were played by a regular company of voice actors. These radio dramas were published in physical and digital form, and many have been included as special features on the Blu-Ray releases of The Twilight Zone. The audio remake of “Back There” features actor Jim Caviezel in the role of Peter Corrigan. The adaptation is very close to the original, though extended by about ten minutes and altered to fit the audio-only format. Personally, I feel that Caviezel is a bit underwhelming as Corrigan, but I still enjoy the audio drama as a whole. You can listen to the radio adaptation yourself by clicking here or on the picture above.

The radio show is not the only adaptation of “Back There.” In 1963, Cayuga Productions published a book entitled Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone. The book was subtitled, “13 New Stories From the Supernatural Especially Written for Young People.” While published by Serling’s production company and bearing his name, the volume is actually a collection of short stories written by Walter B. Gibson. A prolific author, Gibson is known for penning over 300 stories about the cult fictional character, The Shadow. Of the 13 stories contained in the book, two of them are adaptations of actual Twilight Zone episodes. These are season one’s “Judgement Night” and “Back There.”

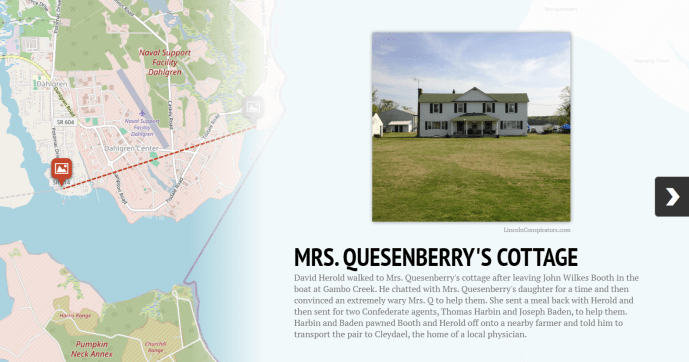

Gibson makes many changes in adapting “Back There” into a short story. In the story, Peter Corrigan is an astrophysicist from New York who has recently been accepted into The Potomac Club, which leans more toward being a scientific society in this version. He travels to D.C. to visit the club for the first time. Caught in a downpour of rain outside of the club, William, the attendant, offers Corrigan a rather antique suit of clothes to wear while his outfit is dried and pressed. In the “monument room,” Corrigan meets with his club sponsors, Millard, Whitaker, and Jackson. Rather than just being three affluent men casually talking about time travel, the trio are experts in parapsychology, biochemistry, and history. Millard recounts his theory about time travel and theorizes that a time traveler may have been accidentally responsible for the stock market crash of 1929. Jackson, the historian, then takes Corrigan on a tour of the club, pointing out all of the old period pieces that were put in around the time of the club’s founding. When attempting to catch up with William to inquire about the status of his clothes, Corrigan slips on the wet marble and falls, hitting his head on the floor. A much younger-looking William comes to his aid, but Corrigan shakes off the fall. Upon being told by a quizzical William that it is not raining, Corrigan decides to take a walk and get some fresh air. Outside, Corrigan sees a horse-drawn carriage and, struck by the novelty of it all, decides to take a ride. During this ride, Corrigan observes sights like the incomplete Washington Monument and soldiers dressed in Union uniforms. He realizes he has somehow traveled back to Civil War Washington. At the Willard Hotel, he spots a newspaper bearing the date April 14, 1865. He flips through the paper until he sees an announcement that President Lincoln and General Grant will be attending the play Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre that evening. [Note: This has a basis in fact. Announcements were made in the evening papers that Lincoln and Grant would appear at Ford’s Theatre.]

Corrigan rushes over to Ford’s Theatre and enters the lobby, but the box office is closed. After a few knocks, a ticket taker opens it up but tells Corrigan he can’t do anything but sell him a ticket. Instinctively, Corrigan buys a ticket while asking to see Mr. Ford, the manager. The ticket taker tells him to check the bar next door or around the backstage door. After no luck at the bar, Corrigan pounds on the locked backstage door until a stagehand opens it. Corrigan tells the stagehand that the President is in danger and that he needs to see Mr. Ford. The stagehand tells him that Mr. Ford isn’t around, but Corrigan attempts to push past him anyway. A brawl ensues, and Corrigan is arrested. At the station, Corrigan learns that the stagehand who tried to get rid of him was Ned Spangler, a name he recognizes as one of Booth’s conspirators.

While Corrigan sits in a cell, the same basic conversation between the sergeant and one of the patrolmen occurs, with the patrolman wanting to secure an extra guard for Lincoln and the sergeant telling him to forget it. The only real change in the conversation is how the sergeant notes that General Grant is going to be with Lincoln at the theater, so the President will be guarded enough. Then, a handsomely dressed man enters the police station and introduces himself as “Bartram J. Wellington, M.D.” He tells the sergeant that he is in the government service as part of a mental branch that is tasked with helping misguided folks who see assassinations and plots everywhere. Not wanting to be stuck in a prison cell, Corrigan agrees to go with Wellington. On the way out, Corrigan tells the patrolman that Grant will not be at Ford’s that night, and, just then, a message comes into the station announcing the same.

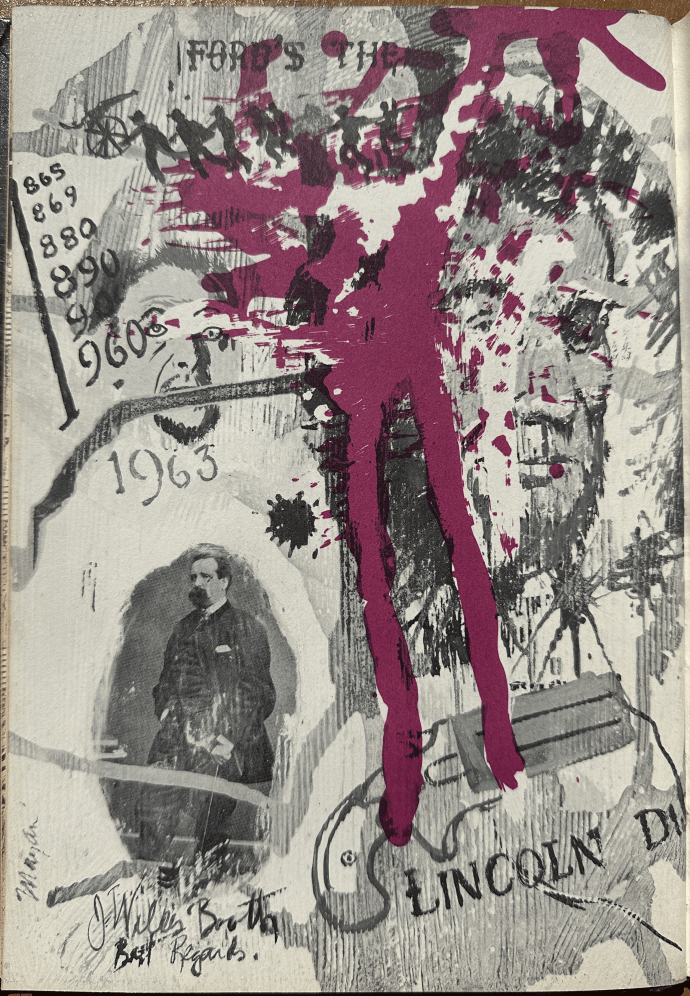

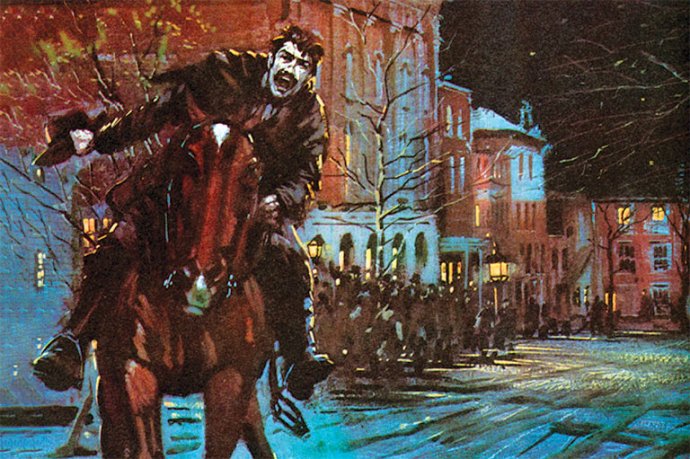

In the 1963 edition of Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone, each short story was accompanied by an illustration by artist Earl Mayan. This is Mayan’s collage for “Back There.” (Click to enlarge)

Corrigan and Dr. Wellington walk to the National Hotel, where Wellington is staying. Not wanting to appear crazy and seeing that there are still two hours before the play begins, Corrigan briefly drops the matter of Lincoln’s assassination. In his room, Dr. Wellington asks Corrigan about himself and how he came to believe the President was in danger. He asks if Corrigan has suffered any accidents lately, and Corrigan points out the bruise on the back of his head from his fall in the club. Wellington pulls out a handkerchief, soaks it in a liquid, and wraps it around Corrigan’s head like a bandage. He then pours Corrigan a drink, which he insists Corrigan take to relax. Wellington then leads Corrigan to believe that he has convinced him of the legitimacy of his claims. Wellington suggests sending a messenger to the surgeon general’s office so that they might be granted an audience with the President. Corrigan lies back and rests as Wellington exits, ostensibly to get help. However, then Corrigan hears the sound of a key locking him in the room. He attempts to stand but finds that he can’t. His body feels paralyzed. He can only pull the handkerchief bandage off his head, and he notices the initials JWB in the corner. His mind tries to understand:

“‘Bartram J. Wellington…B-J-W…B-J-‘ Corrigan’s breath came with a hard gasp. ‘J-W’ Another gasp – ‘J-W-B…J-W-B.’ His mind, still alert, turned those initials into a name: ‘John Wilkes Booth!'”

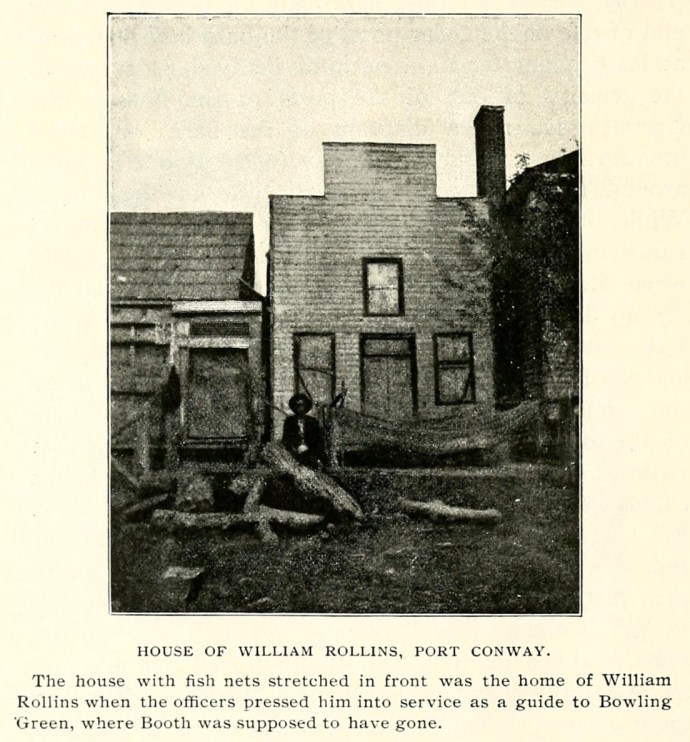

Corrigan passes out but is awakened by the sound of the patrolman entering the room. Corrigan asks for the time, and the patrolman replies that it is 10 o’clock. It’s not too late! The pair get into a carriage outside the National and rush towards Ford’s Theatre. The patrolman tells Corrigan that he started investigating Wellington after his appearance at the station. He discovered there was no Dr. Wellington nor a government service dealing with the mentally ill. After learning Wellington matched the description of the actor, John Wilkes Booth, the patrolman rushed to his room at the National Hotel and procured the key. The pair rush to Ford’s Theatre as fast as they can, with the patrolman showing other carriages, horses, and pedestrians out of their way.

Just as they arrive at the theater, a crowd of panicked people come rushing out of the door, announcing that the President has been shot. Corrigan shouts that it was Booth who shot the President and that he was now on his horse galloping off toward Maryland. A group of theatergoers grab Corrigan, convinced the only way a person on the street could already know this information was if he was involved in the crime. An angry mob descends on Corrigan before the patrolman manages to break through the throng and get Corrigan back into the carriage. The patrolman sends the carriage off, telling the driver to get Corrigan far away from there. A dazed and battered Corrigan lies in the back of the carriage as it rapidly moves through the streets. The driver takes Corrigan to the Potomac Club, and he wearily ascends the stairs and knocks on the door.

When the club door opens, Corrigan is greeted by William, this time looking quite old once more. William informs Corrigan that the time is six o’clock and that his suit is now dried and pressed. Corrigan realizes he has arrived back to the present. He changes into his dried suit and reenters the monument room. He finds that a fourth man has joined Millard, Whitaker, and Jackson. This man is the spitting image of the patrolman who came to Corrigan’s aid, and he tells the story of his great-grandfather, who attempted to save Lincoln’s life with the help of a crackpot who was never heard from again. Corrigan says nothing about his experience in the past to his friends, nor anything about time travel in general. On his way out of the club, he asks William if he had a great-grandfather who worked at the club. William responds that his great grand-uncle, also named William, was the doorman at the club during the Civil War. Reflecting on his experience, Corrigan waits for a cab outside the club. Just as one arrives to take him to the airport, William returns and hands something to Corrigan:

“‘This was in the pocket of that old-time suit you were wearing,’ said William. ‘So I suppose it must be yours. Good night, Mr. Corrigan.’

Soon the cab was speeding down along a smooth street into the blaze of lights that represented downtown Washington. They passed the now completed Washington Monument, which was illuminated to its full height; and off beyond, Corrigan saw the stately pillars of the magnificent Lincoln Memorial. Then, as the cab reached the bridge leading to the airport, Corrigan studied the printed cardboard strip that William had handed him.

Deliberately, he tore the strip in half; then again, again, and again. Near the middle of the bridge, Corrigan tossed the pieces from the cab window. Caught by the night breeze, they fluttered over the rail and down to the broad bosom of the Potomac River.

Those scattered scraps were all that remained of a unique collector’s item – the only unused ticket to Ford’s Theatre on it’s closing night of April 14, 1865.”

While not a true adaptation of Serling’s original teleplay, I do enjoy Walter Gibson’s take on “Back There.” This version gives a little more action to the story, with Corrigan and the patrolman rushing to Ford’s. And the switch of the JWB handkerchief for a ticket is a nice touch.

Final Thoughts

Marc Scott Zicree, author of The Twilight Zone Companion, is not a fan of “Back There,” writing:

“For all the intellectual fascination of its premise, however, ‘Back There’ is a dramatic failure. The reason is obvious: from the outset the conclusion is known; Lincoln was assassinated, therefore Corrigan won’t be able to intercede. Says Buck Houghton [the producer of The Twilight Zone], ‘I think that when you play ducks and drakes with the shooting of Lincoln, your suspension of disbelief goes to hell in a bucket.'”

While I certainly understand this critique, I still feel that this episode is more than a foregone conclusion. Yes, new viewers will likely go into it pretty confident that Russell Johnson won’t be able to save Lincoln, but watching the attempt play out is still compelling. This opinion was shared by the associate producer of The Twilight Zone during its second season, Del Reisman, who later recalled:

“We had a big struggle on that topic in the sense that we know that Lincoln was assassinated. So when the ending is already known by everyone, where’s the suspense? My feeling was that the suspense lies in how the character does it, how he tries to prevent the shooting. That’s the interest. It doesn’t matter that we know that Lincoln was assassinated. We want to know how Russell Johnson’s character does this, his approach to it… Incidentally, that theme comes up a lot, whenever you’re dealing with historical storytelling. I was working at Fox television at the time when they did The Longest Day. That was the Cornelius Ryan story, a World War II all-star movie about the assault on Normandy Beach and the move into the beachhead. A very good producer on the Fox lot said, ‘This is gonna flop.’ I asked why and he said, ‘Because we all know that the landing succeeded.’ I argued that the story is about how they did it. It’s the same thing on the wonderful The Day of the Jackel, which was the fictional tale of the attempted assassination of Charles de Gaulle. In effect, production people were saying, ‘We know that Charles de Gaulle was not assassinated, so what’s the suspense?’ It’s in how they attempted it. I felt that way about ‘Back There’ and I liked it.”

While some episodes like “Eye of the Beholder” or “Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?” are built around a single twist at the end, “Back There” gives us multiple twists and turns. It’s true that Johnson is undoubtedly hamming it up at times as Corrigan, especially in the scene where he writhes around the floor somewhat laughably knocking things over, but there is still a sense of humanity in his performance. The look on his face at the very end of the episode, when he finds the JWB handkerchief in his pocket, perfectly encapsulates a man who knows he’s experienced something remarkable but is completely unsure how to make sense of it all.

One of my other favorite parts of “Back There” is the unknown nature of the mechanism that sent Corrigan back to 1865 in the first place. There’s no convoluted time machine like in “Execution” or “No Time Like the Past.” A strange feeling comes over Corrigan, and he just appears in the past. We accept this because it’s The Twilight Zone we’re dealing with, and the Twilight Zone operates under its own rules, rarely providing an explanation. There’s an elegance in that that doesn’t exist in the world of complicated sci-fi time travel movies or shows.

As far as episodes of The Twilight Zone go, “Back There” may not be considered a classic by many. However, it will always hold a top spot on my list. This is not just because it deals with a subject that I find fascinating but because the episode is everything I want from The Twilight Zone. The best episodes not only keep you thoroughly engaged while you’re watching but also give you something to think about when they are over. “Back There” invites us all to reflect on the concepts of time, fate, and our own ability to influence the future. As Rod Serling’s ending narration states, “Back There” is a thesis for each of us to take and mull over in our own way.

References

The following sources were consulted in composing this post

- The Twilight Zone: Unlocking the Door to a Television Classic by Martin Grams, Jr.

- As Timeless as Infinity: The Complete Twilight Zone Scripts of Rod Serling, Vol 10 edited by Tony Albarella

- The Twilight Zone Companion by Marc Scott Zicree

- Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone adapted by Walter Gibson

- The Twilight Zone Podcast by Tom Elliot

- Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination by Thomas Bogar

- Images and information about the MGM backlots came from the websites The Judy Room and Phantom of the Backlots.

- All footage from The Twilight Zone is owned by CBS and is used here under fair use.

A very special thanks to Richard Sloan and Scott Schroeder for lending me their expertise for this project.

*The ten Twilight Zone episodes featuring music from “Back There” are: “To Serve Man,” “Death Ship,” “No Time Like the Past,” “The Parallel,” “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” “Uncle Simon,” “Probe 7, Over and Out,” “You Drive,” “The Masks,” and “Stopover in a Quiet Town.”

Recent Comments