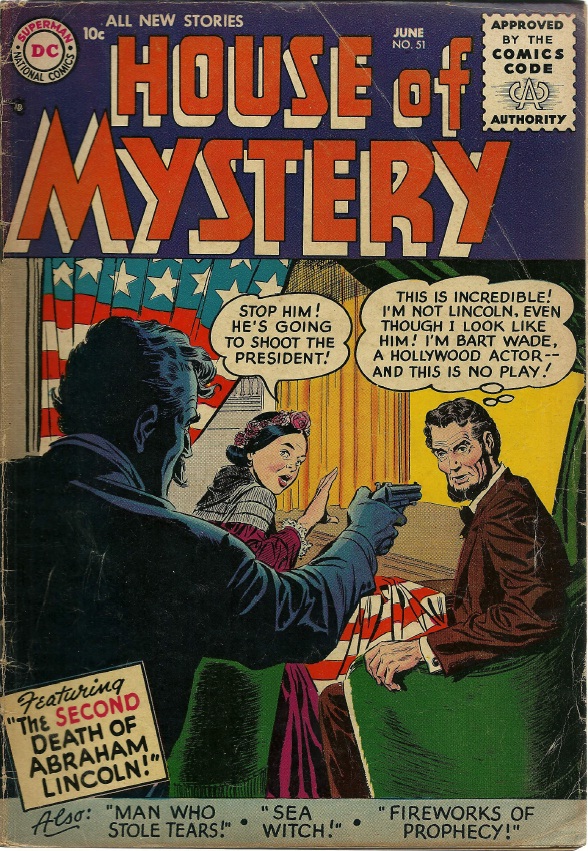

Thank you to Richard Sloan for sending this unique, albeit strange, comic book from his collection. You can see excerpts of other Lincoln assassination comic books here.

Thank you to Richard Sloan for sending this unique, albeit strange, comic book from his collection. You can see excerpts of other Lincoln assassination comic books here.

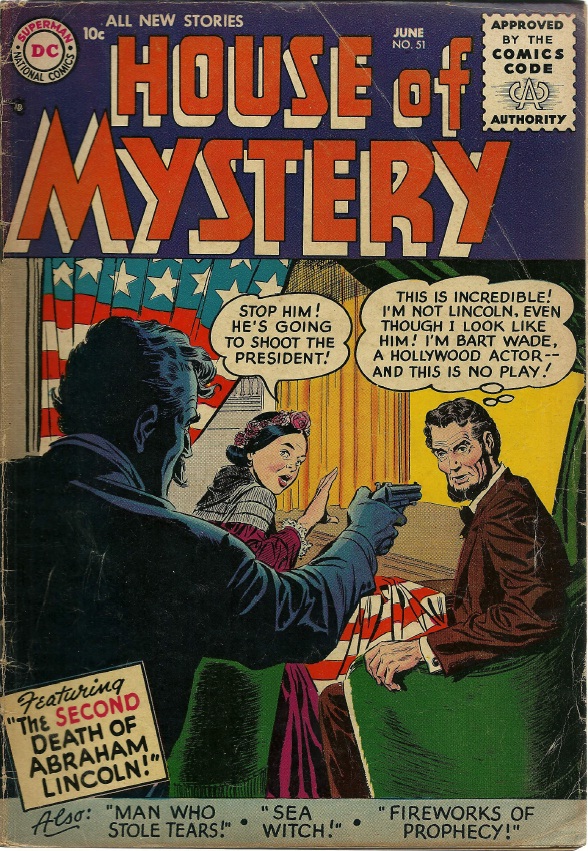

On May 6th, 1865, the British magazine, London Punch, published the following poem which expressed the international sense of shock and sympathy over the unprecedented assassination of the 16th President of the United States of America:

Abraham Lincoln, Foully Assassinated

You lay a wreath on murdered Lincoln’s bier,

You, who with mocking pencil wont to trace,

Broad for self-complacent British sneer,

His length of shambling limb, his furrowed face,His gaunt, gnarled hands, his unkempt, bristling hair,

His garb uncouth, his bearing ill at ease,

His lack of all we prize as debonair,

Of power or will to shine, or art to please,You, whose smart pen backed up the pencil’s laugh,

Judging each step, as though the way were plain:

Reckless, so it could point its paragraph,

Of chief’s perplexity, or people’s pain.Beside this corpse, that bears for winding-sheet

The Stars and Stripes, he lived to rear anew,

Between the mourners at his head and feet

Say, scurrile-jester, is there room for you?Yes, he had lived to shame me from my sneer,

To lame my pencil, and confute my pen —

To make me own this kind of princes peer,

This rail-splitter a true-born king of men.My shallow judgment I had learnt to rue,

Noting how to occasion’s height he rose,

How his quaint wit made home-truth seem more true,

How, iron-like, his temper grew by blows.How humble, yet how hopeful, he could be;

How in good fortune and in ill the same;

Nor bitter in success, nor boastful he,

Thirsty for gold, nor feverish for fame.He went about his work — such work as few

Ever had laid on head and heart and hand —

As one who knows, where there’s a task to do,

Man’s honest will must Heaven’s good grace command.Who trusts the strength will with the burden grow,

That God makes instruments to work His will,

If but that will we can arrive to know,

Nor tamper with the weights of good and ill.So he went forth to battle, on the side

That he felt clear was Liberty’s and Right’s,

As in his peasant boyhood he had plied

His warfare with rude Nature’s thwarting mights –The uncleared forest, the unbroken soil,

The iron bark that turns the lumberer’s axe,

The rapid, that o’erbears the boatman’s toil,

The prairie, hiding the mazed wanderer’s tracks,The ambushed Indian, and the prowling bear —

Such were the needs that helped his youth to train:

Rough culture — but such trees large fruit may bear,

If but their stocks be of right girth and grain.So he grew up, a destined work to do,

And lived to do it – four long-suffering years;

Ill-fate, ill-feeling, ill-report, lived through,

And then he heard the hisses changed to cheers,The taunts to tribute, the abuse to praise,

And took both with the same unwavering mood;

Till, as he came on light from darkling days,

And seemed to touch the goal from where he stood,A felon hand, between the goal and him,

Reached from behind his back, a trigger prest, —

And those perplexed and patient eyes were dim,

Those gaunt, long-laboring limbs were laid to rest!The words of mercy were upon his lips,

Forgiveness in his heart and on his pen,

When this vile murderer brought swift eclipse

To thoughts of peace on earth, good-will to men.The Old World and the New, from sea to sea,

Utter one voice of sympathy and shame!

Sore heart, so stopped when it at last beat high;

Sad life, cut short just as its triumph came.A deed accurst! Strokes have been struck before

By the assassin’s hand, whereof men doubt

If more of horror or disgrace they bore;

But thy foul crime, like CAIN’S stands darkly out.Vile hand, that brandest murder on a strife,

Whate’er its grounds, stoutly and nobly striven;

And with the martyr’s crown crownest a life

With much to praise, little to be forgiven!

What makes this poem unique is its author. This specific poem was written by British playwright, Tom Taylor. It was Tom Taylor’s play, Our American Cousin, that Lincoln was watching when he was assassinated. While Laura Keene had made improvements to Tom Taylor’s original version of the play, you can’t help but wonder if Mr. Taylor was motivated to write this poem over his perceived guilt at writing a play so appealing, that it lured Lincoln to his death.

References:

The poets’ Lincoln by Osborn Oldroyd

On this, the 148th anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination, I reflect on my own interest in the tragedy at Ford’s Theatre. In high school, I was in speech and drama. One day, a good friend of mine who had soundtracks to many musicals, starting playing Assassins by Stephen Sondheim in his car. At first I thought, “what a dark thing to write a musical about”. However, as I listened deeply to the lyrics, I was struck by how little I knew about the history of the people I heard. The songs spoke of their misguided hopes and I was convinced to learn more about these people I knew little to nothing about. I had heard of John Wilkes Booth of course, but only as the crazy, racist actor who shot Lincoln. Beyond that, he was a mystery to me. The more I read about Booth, the more I felt him to be such an oddity compared to the other Assassins. In his song, entitled “The Ballad of Booth”, he sings of his crime, “Let them cry ‘dirty traitor’, they will understand it later.”

Despite all of the books that I’ve read on the subject since hearing this song for the first time, I still don’t truly understand what made Booth commit his deed. There are many wonderful books that expertly dissect Booth, and the authors provide wonderful insights as to why he acted as he did. However, the more I read, the more impossible I find it to put Booth into just one of these corners. That is what keeps me drawn to this history. Even after all this time, Booth and his band of conspirators are still an enigma to me. So I will continue to read and learn about them. This is what helps keep Lincoln’s legacy alive, in my eyes. When we dismiss the men and women involved in the ‘dreadful affair’, we allow Lincoln to die. When we claim to know all we need to know about the Lincoln assassination, we end his story. So while my interest in Lincoln may be focused on the final chapter of his life, to me, that chapter will never close. As long as others feel the same as I do, then Abraham Lincoln will never die.

This post is just a friendly reminder to all the email followers of this blog that the much anticipated docudrama “Killing Lincoln” debuts tonight at 8pm EST on National Geographic Channel! Make sure to watch it and post your thoughts and comments about it here or on Roger Norton’s Lincoln Discussion Symposium.

While I’m waiting for the debut, I’m checking out the show’s official website which contains interviews with the cast, clips from the film, and production stills. National Geographic has also created a phenomenal interactive timeline of Booth’s conspiracy and manhunt that you absolutely need to check out!

So remember, “Killing Lincoln” tonight at 8 pm EST on NatGeo. Don’t miss it!

I’m pleased to announce that there are four new galleries in the Picture Galleries section of the site. All four of them consist of drawings and engravings regarding John Wilkes Booth’s assassination of Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre on April 14th, 1865. Instead of putting all the drawings of the events that took place at Ford’s together, I’ve divided the actions into four sections.

| The first is called “Sneaking Up” and these images (only three at this point) show John Wilkes Booth in the moments before shooting Lincoln. | The next section is called “The Shot” and consists of the many images of John Wilkes Booth pulling the trigger of his single shot derringer. |

| The third section is entitled “The Leap“. These drawings show John Wilkes Booth’s leap from the president’s box after shooting Lincoln and wounding Major Henry Rathbone | The last section demonstrating Booth’s havoc at Ford’s Theatre is called, “On the Stage“. These drawing show Booth brandishing his bloodied knife while making his way across the stage into the wings. From here Booth exited the back of the Theatre and escaped onto Baptist Alley. |

I hope you enjoy these new additions to the site.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln at the hands of John Wilkes Booth was a defining moment of American history. It was a national tragedy the likes of which we had never experienced. It turned Lincoln into a martyr and changed the course our country would take after a devastating Civil War. For this reason, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln has become perfect fodder for the imaginative minds of comic book writers. Through this artful medium, Lincoln’s assassination has been remembered, revised, and completely reinvented to match the worlds in which superheroes like Superman, Batman, The Flash, and others exist. Most references to the assassination in comic books are brief but a select few have devoted serious attention to America’s great drama of April 14th, 1865.

The Assassination Remembered

Several comic books briefly mention the assassination of Abraham Lincoln as it occurred. Occasionally, the main character is somehow thrown back through time or enters a parallel world to witness it. They may interact in the narrative, but the ending is still the same.

The Assassination Revised

While reminding us all of the past is nice, it isn’t very superhero-y. More often, the death of President Lincoln is averted due to the help of a hero, or because this is a parallel world where his assassination never occurred in the first place.

The Assassination Reinvented

In these versions, the normal history is changed drastically for the comic book world.

As entertaining as that rendition is, however, my favorite incarnation of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in the comic book realm is this 1971 issue of The Flash:

From what I can gather from sources online, the Flash travels forward in time to the year 2971. He enters a world which once contained a united Earth. However a dispute has broken out between Earth East and Earth West and there is Civil War once again. The beginning of the comic leads with a future Lincoln getting disintegrated by a future John Wilkes Booth.

The Flash is rightly confused by how this is possible.

It turns out the future scientists created a robotic Abraham Lincoln to lead them through the Civil War. He contained Lincoln’s wit and wisdom, and also the ability to calculate the consequences of people’s actions.

Booth makes his escape to Earth East using a jet suit.

The Flash chases after him, but gets trapped when Booth ties him up with a future chain that squeezes him harder and harder.

Booth jets off again to meet his master, an evil mastermind named Bekor. He turns over the murder weapon he used to kill Lincoln to Bekor. Bekor betrays Booth and shoots him with the disintegrator. Bye Bye, Booth. When Bekor kills Booth though, Robot Abraham Lincoln remerges out of the gun. Apparently, using his robot brain, Lincoln predicted someone would try to take his life. So he carried around his anti-disintegrator pocket watch.

He turns the table on Bekor using his good old fashioned wrestling skills.

By then, The Flash has managed to escape the squeezing chains and rushes to Bekor’s lair. He manages to get Lincoln out of the lair before it self-destructs. Lincoln continues as President of Earth, using his 19th century wisdom to lead this troubled, 30th century world. This is a fun and entertaining reinvention of the assassination of Lincoln.

There are many other comic books that include references to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln with more coming out every year. As long as Abraham Lincoln continues to be an important part of the American story, his death will continue to find a place within their multicolored pages.

When the unconscious form of Abraham Lincoln was brought out of Ford’s Theatre onto Tenth St., the men carrying the President were unsure of their destination. The street was chaotic and getting crowded with countless individuals having been drawn to Ford’s doors after hearing the dreadful news being shouted through the streets. Many would later claim to have been one of the men who transported the Great Emancipator’s frame out of Ford’s and onto the street. So many in fact, that he only way all of the accounts could be true is if Abraham Lincoln was “crowd surfed” away from the theatre. The commotion of the citizens and soldiers on Tenth street startled a young boarder across the way named Henry Safford. Having spent the previous night doing his part, “with the rest of the multitude in the celebration of Lee’s surrender,” Safford was preparing for a restful evening in his rented room on the second floor of the Petersen house. He threw open the window and called to the crowd of former Ford’s audience members, inquiring about what had occurred. Their reply of, “The President’s been shot,” startled the 25 year-old man. Safford was soon down at the door of the house, watching the crowd and keeping a close eye on Ford’s entrance for signs of a wounded, or dead, President. When the soldiers carrying Lincoln finally emerged, Safford, noticing their lack of a set destination called out, “Bring him in here!” Lincoln’s body was transferred inside of the Petersen house, and Safford led the troops into a back bedroom on the first floor. Though Safford would have been more than happy to surrender his own bed and room for the President, climbing another set of stairs to the second floor would have been too inconvenient. Safford, and other boarders in the Petersen house, would spend the night assisting the doctors by providing hot water and mustard plasters.

Abraham Lincoln died in the Petersen House at around 7:22 am on Saturday, April 15th. With his death, a martyr and a shrine were born. On Sunday morning, 24 hours after Lincoln’s death, an artist by the name of Albert Berghaus arrived in Washington. Berghaus was an illustrator for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and specialized in created sketches of historical events from eyewitnesses. These sketches would be transformed into woodcuts and then published. Berghaus created this sketch of the events at Ford’s Theatre:

In addition, Berghaus visited the Petersen House in hopes of sketching the room and scene of Lincoln’s demise. He employed the help of Petersen’s boarders to describe the individuals who were present in Lincoln’s final moments. His final sketch which was published in the April 29th issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was this:

The drawing was combined with the following affidavit:

“We the undersigned inmates of 453 Tenth street, Washington, D.C., the house in which President Lincoln died and being present at his death, do hereby certify that the sketches of Mr. Albert Berghaus are correct.

Henry Ulke

Julius Ulke

W. Peterson [sic]

W. Clarke [sic]

Thomas Proctor

H. S. Saffard [sic]”

In recognition for their help in helping him create the sketch as accurately as possible, Berhaus included five out of the six above named men in his drawing:

Julius and Henry Ulke – Brothers, photographers, and natural history buffs. It was said the Ulke’s room in the Petersen house would have been unfit for the President as there were too many beetle specimens and scientific instruments cluttering up the space.

William Petersen – German tailor and owner of the house. It was written that Petersen was a great admirer of Andrew Johnson due to the fact that he had been a tailor himself who rose to such a high position in life.

Henry Safford – 25 year-old War department clerk. According to one source, when Edwin Stanton requested a man trained in short hand to take down statements, Safford recommended a nearby neighbor Corporal James Tanner.

The only member of the Petersen household not illustrated by Berghaus was William Clark, a 23 year-old clerk in the Quartermaster’s department. This will come into play later.

Countless other artists, period and modern, would draw their own interpretations on Lincoln’s death chamber. Every drawing, including Berghaus’, would place too many people in the small room. The 17’ by 9 ½’ back bedroom of the Petersen house has been coined the “rubber room” due to its ability to expand and contain so many people all at the same time. While Berghaus’ drawing was cited by the Petersen house residents as being the most accurate – mainly due to Berghaus’ level of detail in duplicating the details in the room – Henry Safford was honest about the rubbery-ness in the drawing: “Not all of the noted men pictured were present at the time, but had been within a few hours of the death of Lincoln.”

Fast-forward fifty-six years. In 1921, the only remaining Petersen house resident was Thomas Proctor.

Proctor had moved from Washington, D.C. and had established himself as a prominent lawyer in New York. He married, was widowed, and in the early 1900’s began a gradual mental decline. By 1915, he had lost all of his money and had become an inmate of New York’s Blackwell’s Island, a prison and poorhouse. Still, some of his old friends and acquaintances remembered the stories he would tell of Lincoln’s last night. On Friday, September 30th, 1921, Thomas Proctor was visited by a reporter from the Associated Press. They spoke of his experiences half a century before. The next day, a news article was published across the nation:

Apparently the poor pauper Thomas Proctor was the gracious man who gave up his bed for the dying President. After reading this story, another living witness to the events of the Petersen house was intrigued. Dr. Charles Leale, the young army surgeon who first tended to the wounded President, arranged a visit with Mr. Proctor:

As this article demonstrates, Thomas Proctor’s mental state is not what it once was. Dr. Leale, though older than Thomas Proctor, must have observed the fragile mind of the man he conversed with. This visit was obviously short, and consisted of Dr. Leale leaving with little in the way of reminiscences.

This news regarding Thomas Proctor as the tenant of the bed in which Lincoln died, was the start of a controversy that stretched nationwide. At first, some papers tried to completely blow off Proctor, stating that his whole story was the invention of a troubled mind. Then, when Berghaus’ engraving came forward as evidence to Proctor’s attendance in the Petersen house, many papers declared him vindicated. Still the debate continued, with two other individuals claiming to have been the occupant of the bed in which Lincoln died. The most convincing of these claimants was the late William Clark, whose face is not included in the Berghaus engraving but whose name accompanies the affidavit attached to it. Though Clark had died in 1888, his friends wrote to the newspapers about how he was the rightful occupant of the bed and room in which Lincoln died. Suddenly, 56 yeasr after the fact, there were two legitimate groups vying for the honor of knowing the man who gave up his bed for Lincoln. The friends of Thomas Proctor used Bergahus’ engraving as evidence, while the friends of William Clark used a letter written by Clark a few days after the assassination as their evidence:

“…The same mattress is on my bed and the same coverlid covers me nightly that covered him while dying…”

The correct answer, as many reading this already know, is that the room and bed in which Lincoln died belonged to William Clark. The debate that surrounded Thomas Proctor was probably not his own doing. As we can see from his interview with Leale, Proctor needed to be led in even basic conversation. The memory of his friends were mistaken that Proctor owned the bed in which the President died and therefore led the practically senile man to that conclusion. In support of this hypothesis is an 1899 article written about Proctor in which he correctly admits that the room and bed in which Lincoln died belonged to Clark. In fact, through his own 1899 article and an 1895 article written by Henry Safford, we learn that Thomas Proctor and Henry Safford were roommates in the Petersen’s second floor apartment. Proctor was there and helped attend to the President, but the honor of the death room belonged to William Clark.

Yet the question remains, why is it that Proctor and all the other members of the Petersen house are included in Berghaus’ sketch, and yet William Clark, the tenant of the sacred room is not? Berghaus sketched all of Clark’s belongings in the room with such detail, and yet the man who lived there was not included. In Clark’s letter to his sister, the same one in which he talks about sleeping in the bed where the President expired, he relates the following:

“I was engaged nearly all of Sunday with one of Frank Leslie’s special artists, aiding him in making a correct drawing of the last moments of Mr. Lincoln. As I knew the position of every one present, he succeeded in executing a fine sketch which will appear in their paper the last of this week. He intends from the same drawing to have some fine large steel engraving executed. He also took a sketch of nearly every article in my room which will appear in their paper. He wished to mention the names of all pictures in the room, particularly the photographs of yourself, Clara and Nannie, but I told him he must not do that as they were members of my family and I did not wish them to be made public. He also urged me to give him my picture, or at least to allow him to take my sketch, but I could not see that either.”

What is interesting here is that Clark seems to have been the only hold out in posing for the sketch. To me, this seems odd. Why wouldn’t Clark allow himself to be saved for posterity along with the others who aided the president in his final moments? For one, Clark was not in his room when the President arrived. After Clark’s passing, his family attempted to alter the record of his involvement. They told Lincoln biographer Ida Tarbell, that it was William Clark who told the soldiers to bring Lincoln to the Petersen house. This was incorrect, and Safford wrote as much to a newspaper after Tarbell’s biography was released. What’s more, Safford included a letter written to him by Thomas Proctor when the latter was in perfect health and memory:

“Mr. Clark, as you know, of course, was not at the Petersen house – on the evening, or during the night, or any part of it, of Lincoln’s death. To the best of my recollection he did not show up till the Sunday morning following. I am positive, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that Mr. Clark was not in the Petersen house at any time during the period in which Lincoln or Lincoln’s body was there, unless he was hidden away somewhere below the first floor, where it would be very difficult for even a cat to secrete itself.”

Safford agrees with Proctor’s idea that Clark was never in the house when Lincoln was there. The article ends with:

“Mr. Safford thinks that it is quite possible that Mr. Clark wrote letters home giving the impression that he was present at the time of the death. In fact, he remembers that on Clark’s return to Washington from his visit, that he (Safford) showed Clark a letter which he had written to his relatives and that Clark said he liked it and believed that he would write about the same thing to his own people. It is possible that he did this, and thus caused the misunderstanding.”

If we are to believe Henry Safford and the younger version Thomas Proctor, William Clark was not present at Lincoln’s death. He did not return to the Petersen house until the morning hours of Sunday the 16th. He arrived in time to hear the stories of what had occurred from the Ulkes, William Petersen, Safford and Proctor. When Albert Berghaus arrived to sketch the room, Clark helped in detailing the many artifacts in his room. However, when Berghaus sketched those who were present for the event, he did not sketch Clark. In his letter to his family, Clark said this was by his choice but what if Berghaus chose not to sketch Clark because he knew Clark was not there when Lincoln died? We are left with two views:

1. William Clark was the only honest man who boarded in the Petersen house with Henry Safford and Thomas Proctor spending years after his death trying to discredit him. In addition, he must also have been the most humble man in the Petersen house since he was the only one to deny having his face saved for posterity in Berghaus’ sketch.

2. William Clark embellished his involvement in Lincoln’s death to include more than, “he died in my room and bed”. He listened to the stories from those who were present and placed himself in the narrative. When Albert Berghaus arrived at the house the day after Lincoln’s death, Clark told him the truth, that he was not there, and therefore was not included in the sketch.

I leave it to the reader to decide what view they feel is most likely.

Epilogue

In the end, the debate about whose bed Lincoln died in sort of puttered out. The Sunday Herald did a wonderful job of getting to the facts and declared the old memory of Thomas Proctor to have been in error. Some other newspapers kept up their support for the pauper who gave his bed for the President, but probably just for the headline. In the end, the mistake was a blessing for the old and confused Thomas Proctor. The attention that was drawn to his story and involvement in history led to an outpouring of sympathy for his living conditions. Through the help of a Rev. Sydney Usher, Thomas Proctor was invited to relocate from the New York City poorhouse. A month after his story first ran he found a new home at the St. Andrew’s Brotherhood Home in Gibsonia, PA. According to a news article, “In his new home, the aged lawyer will be permitted to enjoy many comforts of which he has been deprived…”

Though Thomas Proctor did not rent the room or bed in which Lincoln died, he was a participant in the events that occurred in the Petersen house that night. Along with the Ulke brothers and Henry Safford, Proctor helped the doctors in providing hot water and fulfilling other requests. I have not yet been able to locate when Thomas Proctor died or where he is buried, but it can be assumed that he spent his last years enjoying charity and assistance similar to that he gave the President from those at the St. Andrew’s Brotherhood home.

Not only did Proctor’s mistaken story benefit himself, but it also was used as a seemingly effective advertising campaign for one creative insurance company:

References:

Many articles were consulted to form this post:

Henry Safford’s 1895 account

Thomas Proctor’s 1899 account

Henry Safford’s 1906 account dismissing Clark’s involvement

New York Times article supporting mistaken Thomas Proctor

Mistaken Petersen daughter stating Lincoln died in her bed

Using Safford’s material to reveal Proctor’s error

The Sunday Herald’s article conclusively proving William Clark owned the room and bed

Most images come from PictureHistory.com

“In 1863 or 1864, Robert [Todd Lincoln], on vacation from Harvard, was traveling from New York to Washington and waiting at the train station at Jersey City, New Jersey. While standing in line for tickets on a station platform, Robert was pressed by the crowd against the waiting train – which than began to move forward – and he fell into the narrow space between the train and the platform. He was helpless to escape when a hand grabbed his coat collar and pulled him up onto the platform. Robert turned to find his rescuer to be Edwin Booth, America’s most revered stage actor who was traveling to Richmond, Virginia with his friend John T. Ford (owner of Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.) to fulfill an engagement. Robert recognized the actor and thanked him by name. ‘I was probably saved by [Mr. Booth] from a very bad injury if not something more.”…Robert later wrote that although he never again met Edwin Booth in person, he always had a “most grateful recollection of his prompt action on my behalf.'”

The story above is a fairly well known and publicized coincidence between a Booth and a Lincoln. The book I quoted from is Jason Emerson’s biography of Robert Todd Lincoln, Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert T. Lincoln. Mr. Emerson was a speaker at the 2011 Surratt Society Conference in which he discussed this encounter between the two men. He recounted that, as time progressed, the story of Edwin saving Robert Todd, became more and more grandiose. In one version of the tale, Robert Todd was supposedly knocked unconscious by the fall and Edwin pulled up his limp body. The most extreme incarnation though, was the one that had Robert Todd Lincoln oblivious to the fact that he was on a set of train track as a train came barreling down towards him. With almost superhero speed, Edwin Booth then ran forward and leapt into the air, tackling Robert out of the way of the train just in time.

Though that last version had very little basis in fact, the true story continues to be told over and over by many newspapers, magazines and websites, due the palatable irony that surrounds the characters. We all know how this Good Samaritan tale would one day be eclipsed by a different “Booth and Lincoln” story.

References:

Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert T. Lincoln by Jason Emerson

Recent Comments