In January of 1890, an article appeared in the Century Magazine by John Nicolay and John Hay, the personal secretaries of President Abraham Lincoln. For the past four years, the pair had been releasing regular articles in Century documenting the life and Presidency of their former boss. Nearing the end of their project, this 1890 chapter of their ongoing Abraham Lincoln: A History series was titled “The Fourteenth of April” and covered Lincoln’s assassination. Nicolay and Hay set the scene well, documenting Lincoln’s movements that day and highlighting the fateful events at Ford’s Theatre that evening. When discussing the moments just before the fatal shot was fired, the duo wrote:

“No one, not even the comedian on the stage, could ever remember the last words of the piece that were uttered that night – the last Abraham Lincoln heard upon earth. The whole performance remains in the memory of those who heard it a vague phantasmagoria, the actors the thinnest of specters.”

This claim – that no one could recall the words spoken on stage before the shot was fired – came as a surprise to several people who had witnessed the assassination or had heard the story from those who had been there. While the memory of the last words may have waned in Hay and Nicolay, there were some alive in 1890 who remembered well the last lines of Our American Cousin that were uttered before the building erupted into chaos. Not the least of those who remembered the event vividly was the described “comedian on the stage” himself, actor Harry Hawk.

In 1865, William Henry “Harry” Hawk was a star performer in Laura Keene’s acting troupe. Our American Cousin had been a breakout hit for the trailblazing actress and theater owner when she debuted it in 1858. Even seven years later, the play was immensely popular, so much so that Keene had gone to court against actors like John Wilkes Booth’s brother-in-law, John Sleeper Clarke, who had put on the show themselves without her consent. Even though Harry Hawk had not been part of the original 1858 cast, as part of Laura Keene’s troupe for the season of 1864-65, he aptly played the titular role of the American cousin, Asa Trenchard.

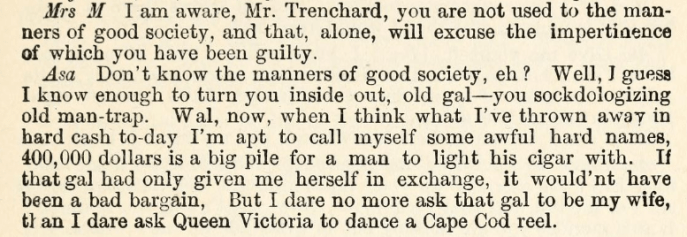

Just before Booth fired his derringer at Ford’s Theatre, Hawk’s character had been upbraided for his lack of proper English manners by the character of Mrs. Mountchessington, played by Ford’s Theatre stock actress Helen Muzzy. The flummoxed Mrs. Mountchessington, unaware that Asa had selflessly burnt the will granting him a large portion of the English estate so that members of the immediate family were not dispossessed of their inheritance, lambasted the backwoods American for not being used to “the manners of good society.” She then exited in a huff along with her daughter. This left Harry Hawk’s character as the only person present on the stage.

So, what were the last lines that Lincoln heard on stage? Well, according to the play’s script, after Mrs. Mountchessington leaves the stage, the somewhat frustrated Asa Trenchard is supposed to call after her with the comment, “Don’t know the manners of good society, eh? Wal, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal – you sockdologizing old man-trap.”

This famous line has gone down in history as the last words Abraham Lincoln ever heard, for according to witnesses, Booth used the laughter that followed this line to help cover the report of his pistol.

There is a minor fly in the ointment, however. What appears in the “script” for Our American Cousin may not be the exact lines that were spoken that night. Our American Cousin was very much a “living play” at the time it was being performed. The original version that British playwright Tom Taylor had written and sold to Laura Keene was very different from the show that became famous. Taylor’s version was a melodrama with some instances of farce. To spice the play up a bit, Keene and her original cast made drastic changes to Taylor’s work and increased the comedic aspects. Most notably, the character of Lord Dundreary was altered from a minor role with only 40 or so lines into the major comic relief of the entire play. Rather than being just a slightly out-of-touch aristocrat, E. A. Sothern, the original actor of Lord Dundreary, wholly reinvented the part, transforming Dundreary into a laughably loveable buffoon with a crazy style who talked with a lisp and uttered his own uniquely rearranged aphorisms such as “birds of a feather gather no moss.” The changes Keene and Sothern made to Tom Taylor’s work are what made the show a hit. Sothern became so popular in the role that he penned his own Dundreary spin-off shows that he acted in for the rest of his life.

By 1865, much of the show had become more structured, but ad-libbing and the alteration of lines were still common. In the years after the assassination, the show continued to evolve as well, making it unclear how much the 1869 printed version of Our American Cousin differs from what was heard in 1865. We know, for example, that Laura Keene herself did some ad-libbing at Ford’s Theatre, adding a line to draw attention to the President’s arrival after the show had started. Another adlib was made after one character stated their line about their being a draft in the English manor house, only for one of the actors to reassure the audience that, with the Civil War now practically at an end, there would no longer be a “draft” in the military sense.

One would think that our best source for the exact words said on stage would be from the man who uttered them, Harry Hawk. In the hours after the assassination, Hawk was interviewed by Corporal James Tanner in the front parlor of the Petersen House, where Lincoln lay dying. While Hawk discussed his placement on the stage and was among the first to formally identify John Wilkes Booth as the assassin, he did not mention the words he had spoken just before the shot. Over a decade ago, I transcribed a letter Harry Hawk wrote to his parents in the aftermath of the assassination. In that letter, Hawk confirms he was “answering [Mrs. Mountchessington’s] exit speech” when the shot was fired, but he does not include his lines.

The genesis of this post was a letter from Harry Hawk that I recently viewed in the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas in Austin. The letter is merely dated “Sept. 21” with no year given. However, based on the reference to the Century Magazine article, we can conclude that the letter was likely written in 1890 or perhaps 1891. Hawk is writing from the Camden House, a lodging establishment in Boston. The recipient of the letter is unknown, but it appears that they originally wrote to Hawk asking him about his experience the night of Lincoln’s assassination. This letter from Hawk is transcribed below:

Camden House

331 Tremont St.

Sept. 21st [1890 or 91]Dear Sir

In reply to yours I will state, first that Mr. John Mathews, W. J. Ferguson, Thos Byrns [sic], Emerson, and myself are the last survivors of the men of that sad fateful event. That is to my knowledge. I haven’t a bill with the cast by me. In contradiction to the statement made by The Century Article last January, that, not even the comedian who was speaking at the time could remember the last words spoken is all rot. I was speaking at the time being entirely alone on the stage, and as I played the character many times after it would be very strange if I did not remember the lines and incidents. They are all indelibly impressed on my mind, and as clear as thought it occurred last night. I have positively refused to be interviewed on account of my friendship for Edwin Booth. And would not wound his feelings by permitting the papers publishing what I did and did not say. A few days after the Graphic article, I was awakened early in the morning at the Lindel Hotel St. Louis, by a reporter for the World, N.Y., to interview me regarding it. The last words spoken on that stage and the last ones dear old Martyr Abe Lincoln heard, these in reply to the old lady Mrs. Muzzy, who had just gone off the stage – I knew enough to turn you inside out – old woman, you darned old sock dolagin man trap

Resp. Yours

Harry Hawk

In this way, Harry Hawk describes the last lines heard by Lincoln as a slight variation of the lines printed in Our American Cousin. While I would like to take Hawk at his word here, we should be cognizant to remember that this letter was written at least 25 years after the events it describes. Despite Hawk’s claim that the lines and incidents are “indelibly impressed” on his mind, human memory is a fickle and unreliable thing. That is why, as historians, we try our best to find sources as close to the event as possible while the memory is still fresh and is unlikely to have been inadvertently altered by the passage of time.

It appears that Hawk stayed true to his word to not discuss the events of that night with reporters so long as Edwin Booth lived. The famous tragedian died in 1893, which is probably why, in 1894, Hawk agreed to be interviewed by reporters. An article about Hawk was published in March by the Washington Post, followed by a slightly different one from a Chicago reporter in April. The second article, republished across the country, described the events at Ford’s Theatre and Harry Hawk’s experiences. In this recounting of the last words said before the shot, Hawk stated, “My lines were: ‘Not accustomed to the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old woman. You darned old sockdologing mantrap.’”

In some other similar articles from Hawk in 1894, the only significant change in the lines given is the use of the word “damned” rather than “darned.”

An engraving of the assassination from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Here we can see Booth brandishing his knife on stage and uttering “Sic Semper Tyrannis” while a stupefied Harry Hawk looks on. In reality, Hawk fled from the stage when he saw Booth running towards him with a knife.

The exact phrasing Harry Hawk used to say his lines in Act 3, Scene 2 of Our American Cousin will never be known for absolute certainty, but through the printed script and Hawk’s own reminiscences from that night, we can get very close to the last words heard by President Lincoln. Regardless of the phrasing, as Hawk uttered these lines, “the audience clapped their hands and laughed in glee, in which the President joined with a smile.” For all the tragedy of that fateful night, we should take some solace in the fact that Abraham Lincoln’s last moments of consciousness were filled with joy and laughter.

Epilogue:

I’ve often heard the Park Rangers at Ford’s Theatre give their presentation about the assassination. As part of their schtick, they tell the audience that Lincoln was shot during the “biggest laugh line of the play” and then recite the printed line above. Other than some nervous laughter from a few who fear they’ve missed the joke, the line regularly goes over like a lead balloon. Part of the problem is that the line alone is just not that funny. It’s the character of Asa Trenchard as the American country bumpkin finally breaking loose and telling his British counterparts “what for” that makes the line funny. There’s also irony that the stuck-up Mrs. Mountchessington claims Asa doesn’t know his manners when he has demonstrated better manners than the entire household by selflessly renouncing his inheritance so that his British relatives would be taken care of. Out of context, the line just doesn’t pack the same comedic punch.

The other issue is likely to do with the word “sockdologizing.” It’s a completely foreign word to a modern audience, which creates confusion. But, in truth, it was a slightly made-up word in 1865 as well. The basis of the word appears to be “sockdolager” which an 1897 Dictionary of Slang struggled to define. The Dictionary of Slang attempts to connect it to the word “doxology,” a religious verse that is sung at the end of a prayer. In this way, a sockdolager could mean something conclusive that settles or ends something. If interpreted this way, Asa Trenchard is criticizing Mrs. Mountchessington for acting like she is the final word on everything, which is ironic since she doesn’t even know what Asa has done, and his news could “turn her inside out.” However, a “sockdolager” was also the name of a type of fish hook that closed via a spring.

Given that the word “sockdologizing” is followed by the phrase “old man-trap,” this line could be interpreted to mean that Asa is calling Mrs. Mountchessington out for her own aggressive barbs and ruses hidden under the facade of her so-called “good manners.” In the end, we can’t be sure how to interpret the word “sockdologizing” in this line, but, at the same time, it really doesn’t matter. The creative wordplay alone invokes the sense of exasperation Asa is feeling, and that, above all, is where the humor comes from.

Recent Comments