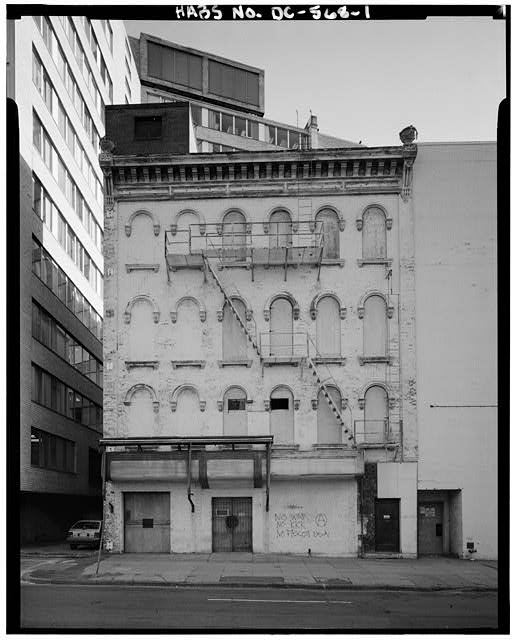

Earlier, I introduced you to Henry Polkinhorn, a Washington, D.C. printer. From his building on D Street, Polkinhorn printed newspapers, books, and a plethora of other custom items. Of all the items he printed over the years, the most sought after item today is the playbill from Ford’s Theatre for April 14th, 1865. In this post we will explore the details of Polkinhorn’s work, in order to identify genuine playbills and later reprints.

We will be utilizing the wonderful, but rare book, The Ford Theatre Lincoln Assassination Playbills: A Study by Walter C. Brenner. Mr. Brenner privately printed this 16 page book in 1937. In it he sorted out the many misconceptions about the playbills and, for the first time, created a tool for identifying and authenticating genuine playbills. In the foreword of his book, Mr. Brenner wisely stated that, when attempting to authenticate a playbill as genuine, “source and pedigree must be disregarded,” and many, “will not prefer to do so.” The simple truth is there is an exceedingly small possibility that genuine playbills still exist outside of libraries, museums, and private collections. In fact, many libraries, museums, and private collections themselves don’t even have genuine playbills. The best of provenance must be ignored when faced with the facts and details of the printed playbill. The evidence within is unbiased and is merely for the benefit and education of those interested in the drama at Ford’s.

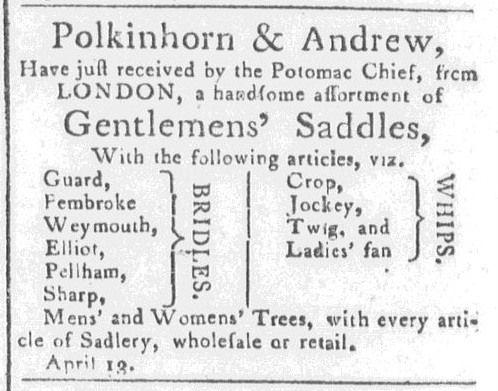

As stated before, Henry Polkinhorn was the regular printer for Ford’s playbills. His association with the theatre started when John T. Ford took over the Tenth Street Bapist Church and started putting on musical performances:

Ford continued using Polkinhorn’s services when he renovated the church into Ford’s Atheneum:

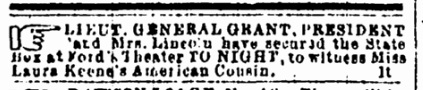

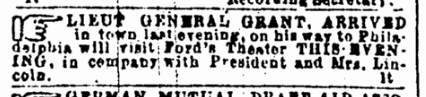

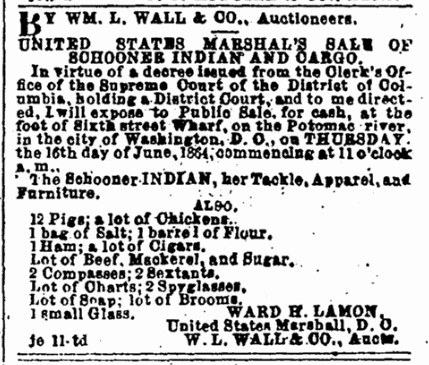

When a fire destroyed most of the building in December of 1862, Polkinhorn helped his customer by purchasing stock so that he could build Ford’s New Theatre. Ford continued to use Polkinhorn for his playbills and printed materials all the way until when the theatre closed for good after the events of April 14th, 1865:

Large advertisement for Ford’s April 15th, 1865 performance of The Octoroon. The performance never occurred as the theatre was closed after Lincoln’s assassination.

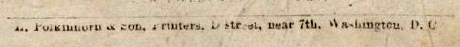

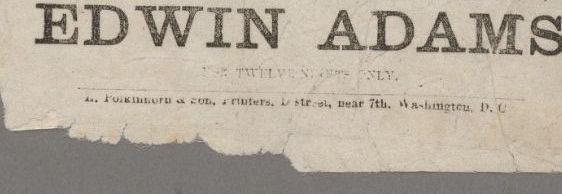

Therefore, when attempting to authenticate a playbill, it is important that it has been printed by “H. Polkinhorn & Son, Printers, D street, near 7th, Washington, D.C.”. This is the final line on the playbill right at the bottom:

Now, just because a playbill says “H. Polkinhorn” at the bottom does not mean that it is genuine. Practically all the later forgeries and reprints include the correct printer.

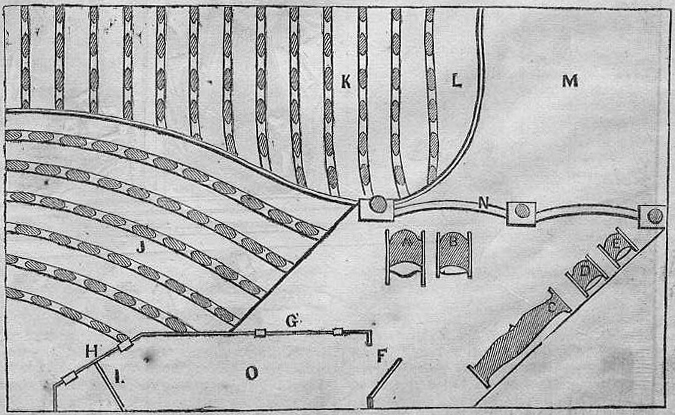

To Polkinhorn, printing the playbills for April 14th was just another job like the day before. As a printer, he kept the previous day’s playbill set up on the press until he was given orders to change it, and then he changed only as much as was necessary. This would save time in the printing process as long as the customer did not call for a completely redesigned playbill. The Harvard Theatre Collection has the bound volume of playbills belonging to John B. Wright, the stage manager at Ford’s. Looking at the playbills leading up to the 14th, Polkinhorn used the identical line of lettering for Laura Keene’s name on the 10th, 11th, 13th, and the 14th. On the 12th, he had to resize her name to make room for an illustration on the playbill, but reverted back on the 13th. On the morning of the 14th, Polkinhorn was printing the bills. At around 10:30 am, Mrs. Lincoln’s messenger arrived at Ford’s to reserve the box for that night. After this announcement happened, John Wright went to Polkinhorn’s printing shop to change the playbill. Originally, there was going to be a special musical performance on the next night, April 15th. On the large poster above you can see on the bottom the announcement for “Honor to Our Soldiers”. This was a song written by Ford’s orchestra director William Withers. With the announcement that Lincoln was attending that night, it was decided that the premiere of the song should coincide with the visit of their honored guest. Therefore, Wright went to Polkinhorn’s to change the playbill to include mention of the song. When Wright arrived, Polkinhorn altered the press to print the new bills. Rather than throw out the bills Polkinhorn had already printed without the song, they were also used that night. This is the reason why there are two issued of playbills for Our American Cousin:

Ford’s Theatre Playbills from April 14th, 1865

After Lincoln was killed, the theatre was shut down never to be used by Ford again. Polkinhorn found that one of his most consistent clients no longer needed his services. He removed the song playbill design off of the press and carried on with his business. As time passed, people clamored for mementoes of the fallen President and the events at Ford’s Theatre. John Buckingham was the door keeper at Ford’s on the night of the assassination. In 1894, he published a short, illustrated book called Reminiscences and Souvenirs of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Before, publishing this book, however, Buckingham got into the business of reproducing playbills from that night. When Buckingham first started printing his “souvenir” playbills is unknown. The earliest I can confirm is by 1879, but it is likely he started much earlier than this. One source states that the reprints were sold on the streets of Washington “a day or two after the tragedy”. What is known is that when Buckingham decided to print his souvenirs he went right back to Polkinhorn’s printing company. Richard Oliver Polkinhorn, Henry Polkinhorn’s nephew, is the one that helped him recreate the bills from that night. Using Polkinhorn’s own press and type, the two printed copies and created an engraving of the first issue playbills. Buckingham started selling the playbills as souvenirs. At first, the reprinted bills had no markings to identify them as reprints. Years later, Buckingham would start stamping them, “Lincoln Souvenir Engraving”, but by then countless numbers had made their way into the public and began masquerading as authentic bills. Buckingham’s souvenir playbills look like this:

John E. Buckingham’s souvenir reprint playbill

So, there are two issues of authentic playbills printed on April 14th, 1865, and one version later printed by Ford’s doorman. Buckingham only reprinted the first issue playbill and so the second issue, the one with “Honor to Our Soldiers”, has been saved from period forgeries. Aside from contemporaneously forged examples, all second issue playbills that exist are most likely genuine. For the first issue playbills, however, careful attention must be paid to identify Buckingham and other reprints.

As well as John Buckingham and Richard Polkinhorn did in recreating the first issue playbills, the devil is in the details. As we will see, Buckingham made his own mistakes and actually corrected mistakes that were present in the original bills, when making his copies. A close look at a genuine bill and a Buckingham copy shows the differences.

The way we know that Buckingham used Polkinhorn’s own type and press is twofold. First, on the back of an 1891 Buckingham reprint there is a stamped note from R. O. Polkinhorn citing his involvement in creating the copies. Second, the type itself is a match for Polkinhorn’s press. One way to identify a bill that used Polkinhorn’s press is the particular type that is used to create the words “THE OCTOROON”. Other period reprints from other printers, like this one housed at the University of Delaware, did not have this specific font type. This clearly identifies it as being from another printer entirely.

On the Buckingham reprints, however, “THE OCTOROON” is in the exact same type as on the original playbills, proving that Polkinhorn’s printing shop was used for the souvenirs.

The most obvious difference between a genuine first issue playbill and a reprint is the final “E” in LAURA KEENE. In genuine bills, the final “E” is perfect. This “E” is consistently undamaged on the previous Ford playbills from the week leading up to the assassination. On the Buckingham reprints, however, the final “E” is marred:

Not only is the “E” damaged, but also the final letters and numbers on many of the lines. According to Brenner this damage was caused by the gauge pins on the press getting in the way. However it happened, it provides the most notable difference between a real playbill and a souvenir.

While the “E” was a mistake on the part of the printer, the pair also fixed mistakes from the original bill. In the genuine first issue bills, right above “The OCTOROON”, it states, “When will be presented BOURCICAULT’S Great Sensation Drama,”. This is a typo. It should read “Great Sensational Drama”. When Buckingham created his souvenirs he corrected it and changed it to the appropriate “Sensational” (See the Octoroon examples above).

In addition, the original bill had an accidental space at the top. Under the heading it states, “WHOLE NUMBER OF NIGHTS 49 5”. There is a space between the 9 and 5 in “49 5”. Buckingham corrected this unnecessary space and changed it to “495”.

In Walter Brenner’s book, he identifies 14 minute differences between Buckingham’s reprint and genuine playbills. From missing words to the vertical alignment of letters, he provides a chart of the changes. If a playbill has correctly passed the above criteria, this book should be consulted and the rest of the details authenticated.

In addition to Buckingham’s souvenirs, many other printers and indiviudals of the period tried their hand at creating false bills. Any playbill that bears the announcement that, “THIS EVENING The Performance will be honored by the presence of PRESIDENT LINCOLN” is a fake.

Forgery

As was mentioned earlier, the playbills were altered when it was ascertained that Lincoln and his guests were attending the night’s performance, however, they were only changed to include lines from the song “Honor to Our Soldiers” and not to announce his attendance. Playbills containing Lincoln’s name are reprints from other printers, and not authentic.

While period fakes are common, there are also modern fakes that often trip people up. Like Buckingham did so many years ago, museums sell reproduction playbills in their gift shops around the country. Ford’s Theatre actually sells a reproduction of the Buckingham reprint. It is attached to a reproduction wanted poster and costs $1.50.

The paper is browned and made to look old, too. They are excellent reproductions but can add to the confusion when someone believes they have the genuine article.

When it comes to Ford’s Theatre playbills from April 14th, 1865, it is important to dismiss any stories of provenance until the bill is authenticated. In Brenner’s book, he mentions a playbill with impeccable provenance. Two signed affidavits accompany it; one written by the owner of the bill and another by John T. Ford himself. In it he states, “I, John T. Ford on oath say that I presented Mr. A. K. Browne with a programme of the play of ‘Our American Cousin’ which I picked up near President Lincoln’s chair when he was assassinated…” This superb provenance is a rare and valued thing for historical artifacts. Unfortunately, the marred “E” on the playbill that accompanied these affidavits prove that it is not a genuine playbill, but instead a Buckingham reprint. The best provenance in the world has to be ignored when faced with unbiased evidence. Despite the affidavit to the contrary, John T. Ford was not even in D.C. when Lincoln was assassinated, and he did not arrive there until the Monday after the shooting. Treasure seekers had cleaned out the theatre box long before he showed up.

As far as relics go, a genuine playbill is a treasured commodity. On its face, it’s an advertisement for a night at the theatre. In the context of history however, it exudes a sense of foreboding. These playbills capture Lincoln’s assassination in a way that no other artifact can. They are the last vestige of Lincoln as he lived, and the gateway to his immortality. While reproductions have been made, only genuine playbills provide the emotional impact of that moment frozen in time. They exist today as silent witnesses to Ford’s last great drama.

References:

The Ford Theatre Lincoln Assassination Playbills: A Study by Walter C. Brenner

Restoration of Ford’s Theatre by George Olszewski

Recent Comments