A visitor of this blog named Justin posed the following question on the “Reconstructing Ford’s Theatre” post:

“Random question – but the rear doors of the theater, are those period to the assassination? Not the actual doors themselves but is Booth’s escape door in the same place as they were the night of the assassination or has the façade been redone?”

Excellent question, Justin. With regard to the location of the doors, the short answer is yes. The large, rolling, scenery door and normal stage door you see on the back of Ford’s Theatre today are both in the same locations as their 1865 counterparts. When Ford’s Theatre was restored in the 1960’s the architectural branch of the National Park Service was able to “definitely reestablish” the locations of the doors.

The answer to the second part of your question, whether or not the rear façade of Ford’s Theatre has changed, is also yes, but this answer will take longer to explain.

In the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination, the government shut Ford’s Theatre down. While it looked as though John T. Ford would regain his theater and even reopen it after the execution of the conspirators, a large public outcry prevented this. The government started renting the Ford’s Theatre building from John Ford before purchasing the structure outright in July of 1866. Even before purchasing the building, however, the government began renovating the theatre. They transformed the interior into a three story office building. The top floor housed the Army Medical Museum. The other two floors of Ford’s housed the Office of Records and Pensions run by the War Department. When the medical museum moved out in 1887, they took over the entire building.

During this time the rear wall of Ford’s was altered to facilitate its new use as an office building. The large, and now pointless, scenery door was bricked up and transformed into a regular sized door. The former stage door, through which Booth escape was bricked up and transformed into a window. If you look closely at the picture below, you can still see the outline of where the scenery door and its rollers once were, having been bricked up into a normal sized door:

On June 9th, 1893, while construction and excavation was being done in the basement of the building, a stone pier near the west (front) end of the building collapsed. It brought down a forty foot section from all three floors above it. It was a tragic accident, crushing and killing 21 War Department clerks instantly. You can read more about the aftermath of that accident here.

While the majority of the damage occurred at the front of the building, it was decided to take down the rear wall to complete the clean up. In this way, the front “face” of Ford’s Theatre, with its decorative and elaborate architectural components, was spared from having a gaping hole put into it. When the interior was rebuilt (again as an office building) the rear wall was also rebuilt, but now it no longer resembled the same wall Booth escaped out of. The new rear wall was made with many windows on all three floors. The new rear door was placed in the approximate area as the old scenery door (centered on the wall). Though a few post-1893 newspaper engravings identify this new door as the one Booth escaped out of, the true location of the former stage door was farther north on the rear wall and was now a window:

Not the door Booth escaped out of. The rear wall of Ford’s was taken down and rebuilt after the 1893 collapse. This door was placed in the approximate location of where the large scenery door had been.

Here’s another picture showing the “new” rear wall and door built after the 1893 collapse:

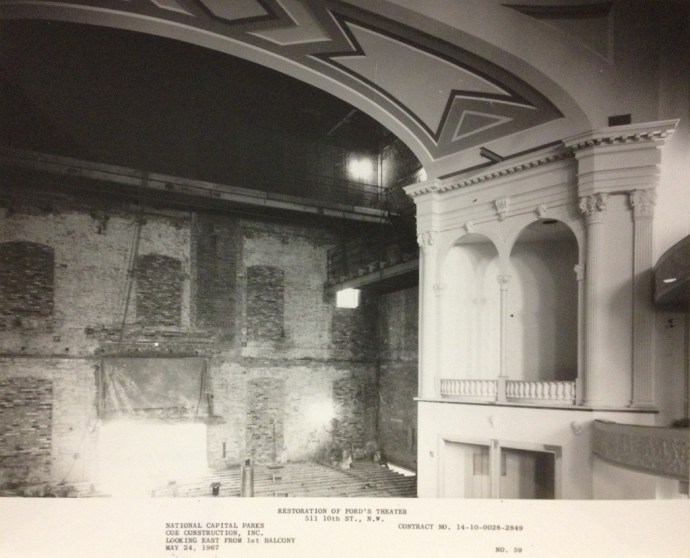

Though the building of Ford’s Theatre underwent additional interior changes from 1893 until it was restored by the National Park Service in the 1960’s, the rear wall remained relatively unchanged during this time period. When the NPS was looking to restore Ford’s they consulted sketches from Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, along with depositions from Ford’s Theatre employees, to determine the original appearance of Ford’s Theatre. Using these materials, they determined the original locations for the scenery door and the original stage door and had them placed back into the walls. They also bricked up the windows that had been added post-1893.

Photograph showing the rear wall of Ford’s Theatre taken during its reconstruction and restoration in the 1960’s. From this view you can see the scenery door that was put back in and the post-1893 windows that have been bricked up.

To sum up, the scenery and stage doors on the back of Ford’s Theatre today are in the same locations as their 1865 counterparts. They are not, however, on the original doorways that Booth would have used. The originally scenery door was bricked up into a normal sized door and the original stage door, through which Booth escaped, was bricked up into a window. Following the collapse in 1893, the whole wall was torn down and then completely rebuilt, removing even the outlines of the original doors. In the 1960’s, the NPS, using sketches and accounts, put the scenery and stage doors back into their proper place while restoring the building.

Thanks for the great question, Justin!

References:

Historic Structures Report – Restoration of Ford’s Theatre by George Olszewski

Recent Comments