In the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination, the authorities (both federal and local) took up the task of hunting down and collecting conspirators and evidence. Lincoln’s own wartime policies gave investigators unprecedented power to arrest and confiscate persons and things relating to his assassination. While casting such a wide net did succeed in capturing the members of Booth’s inner circle, it also inundated the War Department with mountains of evidence. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton appointed three army officers; Colonel Henry Wells, Colonel Henry Olcott, and Lieutenant Colonel John Foster, to help manage and assess the ever increasing paraphernalia. In turn, they reported to Colonel Henry Burnett, who sifted through their materials to find the key evidence to be used in the trial of the conspirators.[1] The voluminous paper materials can be found in the edited book, The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence by William Edwards and Ed Steers, while the original documents can be viewed online (and for free) at Fold3.com. This investigation, however, centers more on some of the collected artifacts found by the War Department: the knives.

During the initial round of evidence gathering, many edged weapons entered the War Department. A knife was collected from the home of a Ms. Mary Cook, a known Confederate sympathizer, who continually celebrated after the assassination and tore down the mourning crepe placed upon her abode.[2] Another knife was taken from a Sergeant Samuel Streett, an acquaintance of Michael O’Laughlen, who was accused of passing two women through his lines at Camp Stoneman on the night of April 14th.[3] A sword was removed from above the mantle at the home of Mary Surratt.[4] In addition to these unrelated weapons, the investigation also managed to acquire the weapons of the conspirators. A knife was found hidden underneath the sheets of a bed at the Kirkwood rented to George Atzerodt. Samuel Arnold was arrested with a knife. Knives belonging to both Lewis Powell and George Atzerodt were recovered on the streets of D.C. the morning after the assassination. Finally, the lead conspirator himself gave up a knife when he was shot in the Garrett’s barn. All of these knives, along with others not mentioned or as fervently documented, left the members of the War Department up to their knees in knives. Therefore, Colonel Burnett began his process of identifying the important items he would need in the trial of the conspirators.

In the end, Colonel Burnett would choose five knives to use in the trial. Four of those knives would be entered as exhibits for the trial, while one knife, Powell’s, was used merely for identification purposes. The handwritten exhibit list for the trial has the following knives listed:

“23. Knife (Atzerodt’s room Kirkwood House)”

“28. Booth’s knife”

“41. Atzerodt’s knife”

“62. Knife found at Mrs. Surratt’s house.”[5]

The selection of which knives to use as exhibits was done very skillfully. With the evidence before him, Burnett realized that, out of those involved in the actual assassination plot, the government’s case was weakest against George Atzerodt and Mary Surratt. Therefore, their blades were touted right along side that of the assassin’s.

During the trial, the first three knives were identified by their finders. Detective John Lee discovered the knife pictured above at Atzerodt’s room in the Kirkwood house. It was hidden, “between the sheets and the mattress.” [6] While found in his rented room and bed, the contents of Atzerodt’s “lost” statement indicate that the knife, along with the other contents found in the room, belonged to David Herold.[7] Further, the statement of Mrs. R. R. Jones (the wife of a bookkeeper at the Kirkwood) notes that, a little after ten o’clock on the night of the assassination, a man ran rapidly past her room, towards Atzerodt’s, and tried to open the door of a room “three different times”. Not being able to get in, the man ran back past her room and down the stairs.[8] This man is supposed to have been Davy Herold. He left his coat, knife, and pistol in Atzerodt’s room, and came to retrieve them for his flight south. Upon finding the room locked and empty, Davy assumed correctly that Atzerodt had lacked the courage to complete his task, and fled. This could explain why, at the Surratt Tavern later that night, Booth bragged to John Lloyd that, “we have assassinated the President and Secretary Seward.” He did not include the death of Vice President Johnson in his boast, as Davy had likely reported the locked and empty room. While the above scenario is just a theory, it is safe to say that the bulk of the contents in Atzerodt’s room at the Kirkwood were under the care of Davy Herold, including the bowie knife recovered. From this point on, the knife found by Detective Lee, probably belonging to Davy Herold, will be referred to as the “Kirkwood knife”. This will eliminate confusion between that knife, and the knife pictured below that Atzerodt himself tossed into the gutter after hearing the news of the successful assassination.

By the afternoon of July 7, 1865, all of the owners of the knives used in the trial were dead. The knives, along with the other pieces of physical evidence, were boxed up and stored. A year later, a request came in to the War Department from Secretary Seward’s former male nurse, Private George F. Robinson. Robinson was asking for a unique keepsake: he wanted the knife Lewis Powell used to stab him and three others. After being approved by Edwin Stanton, the knife was turned over to Robinson, the lone hero on that night of villainy, in July of 1866. Even though Powell’s knife was given to Robinson, this did not affect the four exhibit knives as Powell’s was not one of them. This fact is important to note. Much of the later confusion regarding the assassination knives comes from the assumption that the government retained possession of Powell’s knife. They did not. From 1866 to 1961 the knife was in the possession of the Robinson family. In 1961, the knife pictured below, along with other papers belonging to Private Robinson, were donated to the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. The knife still resides there today. Many journalists and researchers would include Powell’s knife in the government’s holdings during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, and all would be incorrect in this matter.

In 1867, the trial of John H. Surratt, the escaped conspirator, began. The evidence boxes were reopened and many of the same witnesses from the initial conspiracy trial were recalled. The civil trial ended in a hung jury and Surratt was set free. About six months later, another trial was held and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln was relived in that court room as well. That trial also acquits its defendant, President Johnson, who narrowly avoided impeachment. The assassination evidence, now having been taken out, examined, and disorganized twice since the conspiracy trial, was boxed up and stored again. This time, the storage lasted quite awhile.

In 1880, Representative William Springer of Illinois was one of the first to try to claim some of the Lincoln assassination artifacts. He introduced House Resolution 178 on January 23, 1880 calling for, “certain books and mementos in possession of the government to be placed in Memorial Hall of the National Lincoln Monument at Springfield, IL.”[9] It was quickly passed in the House and a Chicago Times journalist reported that it “will no doubt pass the Senate in a few days. The articles called for by the resolution are now in the office of Judge Advocate General Drum, in the War Department, and upon the passage of the resolution will be shipped to Springfield.”[10] While the resolution was eventually passed in both the House and Senate, the annual reports from the National Lincoln Monument Association in 1882 reflect what little became of it: “Concerning relics to be sent from the War and State Departments to Memorial Hall, the only article received thus far is one copy of, ‘Tributes of the Nations to the memory of Abraham Lincoln,’ and is the only one that can be spared. Hon. W. M. Springer has been untiring in his efforts to have the provisions in the joint resolution complied with, but obstacles have presented themselves at various points, and the probability is that we will never receive half of what was ordered in that resolution.”[11] Despite a resolution from Congress, the artifacts and knives stayed in storage as they were deemed too important to let go of, at least for now.

In May of 1899, Judge Advocate General Guido Lieber, was in the mood to do some spring cleaning. Particularly, he wanted to be rid of the trial relics: “These relics are now in a locked cabinet, in a storeroom of this office, in the sub-basement. Very frequently visitors obtain permission to see them, but, owing to the storeroom being filled with files, there are no facilities for showing them, and it takes the time of an employee of this office from his official duties for the purpose.”[12] Lieber contacted the Smithsonian (then called the National Museum) and they were “very agreeable” to receive the relics. Lieber then received permission from the Secretary of War, Russell Alger, to transfer the relics under one condition: the artifacts would forever remain “subject to the control of the War Department.” The Smithsonian did not care for this condition and, during the confrontation that followed, the War Department decided that, “the law did not authorize even a temporary removal of the exhibits.”[13] Again the relics stayed in the Judge Advocate General’s office.

The artifacts would not be freed from their tomb until 1940, 75 years after the assassination. By this time the National Parks Service was in control of Ford’s Theatre and the Petersen House, using the space to exhibit Osborn Oldroyd’s collection of Lincolniana. The official exchange happened on February 5, 1940 when the office of the Judge Advocate General transferred over their materials to the Lincoln Museum (Ford’s). In the list of artifacts, there are four knives mentioned:

“Dagger with which Booth attacked Major Rathbone, and which he carried in his hand as he fled across the stage.”

“Knife used by Payne in his attempt to assassinate Seward.”

“Two knives secured from the effects of the conspirators”[14]

Under the control of thirteen different Judge Advocate Generals, the identities of the knives became scrambled and confused. Powell’s knife was not in the government’s possession and therefore was not turned over to Ford’s. The four knives that Ford’s received are the same four listed in the trial exhibit list. While, at times, it seemed that they were going to be transferred elsewhere, they never left the JAG’s office and the number of assassination knives being held by the government remained unchanged since Robinson was granted Powell’s knife in 1866. Since 1940, the National Parks Service has been trying to sort through this mess of knives with varying degrees of success.

Of all of the knives, the NPS has consistently been correct with their identification of Atzerodt’s knife and the Kirkwood knife. This is partially owing to the fact that the 1940 inventory correctly, but vaguely, lists these two as “Two knives secured from the effects of the conspirators”. If you would visit Ford’s today, you would see Atzerodt’s knife (FOTH 3234) and the Kirkwood knife (FOTH 3231) on display and correctly identified. The main problem and confusion with the knives lies with the assassin’s blade.

At Ford’s there is the above pictured, ornately etched, double edged knife, manufactured by Manson Sheffield Co. of England. It is just less than 12 inches long with a textured bone handle. This beautiful knife has the words, “America”, “The Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave”, and “Liberty and Independence” etched on the blade. Due to this, Ford’s refers to it as the Liberty knife along with its artifact number FOTH 3235. Most visitors, however, know it by another name: Booth’s knife. According to the tag underneath it, this, “horn-handled dagger was used by John Wilkes Booth to stab Major Rathbone after shooting Abraham Lincoln.” No doubt, many have seen the irony of such a patriotic knife helping to commit such an atrocious crime. It makes a poignant impact on those who have seen it. Unfortunately, it’s also a lie. This is not the knife Booth used to stab Major Rathbone. This knife was not recovered from Booth at Garrett’s barn. This knife did not even belong to John Wilkes Booth.

To explain this confusion, it is crucial to look back at the statements and testimonies of those who were with, and captured, Booth. After Davy Herold was caught at the Garrett’s he was transferred to the monitor, Montauk. Here, he gave a statement skillfully trying to conceal his guilt. Though much of Davy’s statement must be taken with a grain of salt, he does produce the following about his traveling companion’s act: “[Booth said] he struck him [Rathbone] in the stomach or belly with a knife. He said that was the knife (pointing to the one which had been shown to the prisoner).”[15] Davy is stating that the knife recovered from Booth at the Garrett’s is the same knife he used to stab Rathbone. While Davy commits to this, he makes no mention of any ornate etchings on the blade of the knife. In fact, Davy, Everton Conger, Luther B. Baker, John “Jack” Garrett, and Boston Corbett all make mention of Booth’s knife in statements and testimonies, but merely describe it as a “bowie knife”. No mention is made of any noteworthy markings on the blade. The term “bowie knife” was used to describe any large hunting knife usually with a crossbar. It is similar to how a derringer, originally the specific maker of the firearm, came to refer to any small pocket pistol.

It is not until the John Surratt trial that a notable description of Booth’s knife is made. Everton Conger gives the following testimony:

“Q: Will you state what articles you took from him?

A: …He had a large bowie-knife, or hunting knife, and a sheath.

Q: Do you know whose make that was?

A: No, sir; the knife has a name on it, but I do not know what it is.”

At this point Conger is going from memory. He has not seen any of the weapons, but recalls the knife had a name on it. He is then shown the weapons:

“(A bowie-knife and sheath and a compass were shown to witness, and identified by him as being taken from the body of Booth. A piece of map was also identified by witness as having been taken from Herold…”

Conger examines the knife and then later is asked how he can be sure it is the same one he recovered from Booth:

“Q: How do you identify the knife?

A: The knife has a spot of rust on it, about two-thirds the way from the hilt to the point, right where the bevel of the knife commences at the end. It was said to be blood, but I have never thought it was myself. It is the same shape and style of knife.

Q: Have you not seen other knives like it?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Have you not seen a great many like it?

A: No, sir; only a few.

Q: You put no marks on it?

A: No. I have no means of identifying it except by the description I have given.

Q: You did not look at the name of the maker?

A: I do not know that the name of the maker is on it. I have looked at it since and noticed the words “Rio Grand camp-knife” on it. I have no means of identifying it except what I have stated, and my general recollection of the style of the knife”[16]

This blade does not bear any engravings or patriotic slogans. It is identified with the name “Rio Grand Camp Knife” and a “spot of rust” said to be blood. This testimony identifying Booth’s knife raises a question. Since Booth’s knife is not the Liberty knife, from where does the Liberty knife come from? This question can be answered by looking at the exhibit list from the conspiracy trial. The Atzerodt knife and the Kirkwood knife are identified and accounted for, so that leaves just two: “Booth’s knife” and “Knife found at Mrs. Surratt’s House”. Since, through Conger’s identification of the knife he helped take from Booth, we know that the Liberty knife is not Booth’s knife, it has to be the “Knife taken from Mrs. Surratt’s house”.

Aside from the description in the exhibit list and its corresponding tag from the JAG’s office, this Liberty knife from Mrs. Surratt’s is very elusive. The conclusion that this author has drawn, is that this knife was likely taken from Mrs. Surratt’s and never properly inventoried. This is not as unlikely as it seems. The Surratt boardinghouse was stripped of anything that could be used as evidence. In an inventory list dated April 24, 1865, the final item mentioned is a “Trunk and contents from Surratt House”. It is written in a different pen and lacks the numeration and specificity of the other items in that list.[17] In fact, the only record of what was in the trunk comes from its return to Anna Surratt on August 18, 1865. The receipt, noting the return of three pistol cases, a sword, one box of caps and other items, does not mention a knife. However it should not mention it because the knife, as an exhibit, would have been retained by the government.[18] While this is a theory, with the mounds of evidence procured during those days, a knife from Mrs. Surratt’s could have easily been overlooked and not inventoried. Therefore, the Liberty knife currently on display at Ford’s as Booth’s knife is not the assassin’s blade but likely an ornate knife recovered from Mrs. Surratt’s. It never belonged to the assassin, and, conceivably, it was never used to harm anyone.

What then, became of the assassin’s blade? According to the 1940 transfer list, four knives were turned over to Ford’s and yet only three are on display. Two of those are correctly identified, while the Liberty knife continues its impersonation of Booth’s knife. The current fate of Booth’s true knife is identical to what it was for over 75 years. Booth’s knife is in storage.

Stored as a generic “knife” with the rest of Ford’s overflow items, it is currently held in the National Parks Service Museum Resource Center in Landover, MD. There it sits, FOTH 3218, encased in protective foam, accompanied by its sheath. While the knife has been found, there is still a mystery to be solved.

Booth’s knife has not always been hidden away in storage. There was a time when it was displayed by Ford’s accurately as Booth’s knife. Books from the 1950s and 60s have pictures of the real, Rio Grand Camp knife, with a spot of rust on the blade, endorsed by the NPS as Booth’s. But suddenly, and inexplicably, it was replaced with the Liberty knife. With the worsening budget cuts the NPS has suffered over the years, the paperwork on the knives at Ford’s is disorganized and, most importantly, they lack a historian to sort it all out. No one seems to know why the knives were switched, but they all trust the unknown predecessor who did so. If the switch was made due to a mere clerical error, the knife doesn’t deserve to sit in storage for another 75 years. It is this author’s hope that this article will merit a re-examination of the knives and the evidence regarding their identification. Hopefully, Booth’s true knife will escape from storage once again and be restored to the Ford’s Theatre Museum.

Booth’s real knife: FOTH 3218

Currently being held in Landover, MD

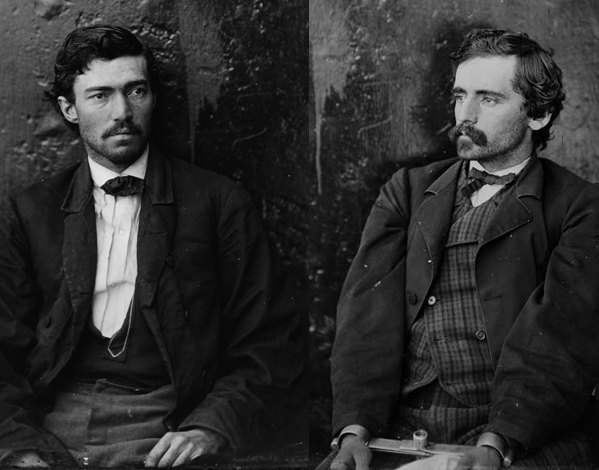

Dave Taylor examining Booth’s true knife in 2012.

Dave Taylor examining Booth’s true knife in 2012.

Photographs by Jim Garrett.

[1] Edwards, W.C., & Steers, E. (2010). The Lincoln assassination, the evidence. (pp. xxii – xxiii). Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

[2] Ibid, (p. 545).

[3] Ibid, (p. 1207).

[4] Ibid, (p. 1165).

[5] NARA. Trial exhibit list. Retrieved from website: https://www.fold3.com/image/249/7390964

[6] Poore, B. P. (Ed.), (1865). The conspiracy trial for the murder of the president, and the attempt to overthrow the government by the assassination of its principal officers. Vol. 1. (pp. 66) Boston, MA: J. E. Tilton and Company.

[7] Steers, E. (1997). His name is still Mudd: The case against Dr. Samuel Alexander Mudd. (p. 122). Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications.

[8] Edwards & Steers. (p. 758).

[9] U.S. House of Representatives. (1880). Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, being the second session of the forty-sixth congress, begun held at the city of Washington, December 1, 1879, in the one hundred and fourth year of the independence of the United States. (p. 297) Washington City, DC: Government Printing Office.

[10] (1880, January 31). Assassination relics: A description of some of the articles Congress will order sent to Springfield. The Cleveland Leader, p. 3.

[11] Power, J. C. (1884). Annual reports of the custodian to the executive committee of the national Lincoln monument association, reports for nine years, from 1875 to 1883 inclusive. (p. 35) Springfield, IL: H. W. Rokker.

[12] (1899, May 24). The Booth relics, they are to be transferred to the national museum. The Minneapolis Journal.

[13] (1904, December 18). The first photographs of the mementos of Lincoln’s assassin. The Washington Times, p. 5.

[14] Copy of a list from the Judge Advocate Generals’ office dated February 5, 1940 in the files of James O. Hall. From the James O. Hall Research Center, Clinton, MD.

[15] Edwards & Steers. (p. 682)

[16] (1867) Trial of John H. Surratt in criminal court for the District of Columbia. Vol. 1. (p. 308) Washington City, DC: Government Printing Office.

[17] Edwards & Steers. (p. 1166). The handwritten page is viewable here: https://www.fold3.com/image/249/7361960

[18]Edwards & Steers. (p. 698).

Author’s note: A version of this article was originally published in the March 2012 issue of the Surratt Courier

Recent Comments