In 1988, Lincoln assassination researchers General William Tidwell, James O. Hall, and David Gaddy published a book called Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln. The volume was the first book of its kind, attempting to unravel the activities of the Confederate Secret Service during the Civil War. The trio documented many plots and instances of guerrilla warfare that Confederate agents undertook to undermine the Union war effort and support the goals of the Rebel South. In addition to documenting the South’s spying apparatus, the authors revitalized the belief of the Union government in 1865, which posited that the Confederate government was behind John Wilkes Booth’s plot against Abraham Lincoln.

There is no denying that John Wilkes Booth had several intriguing interactions with those involved in some way with secret Confederate activities. His conspirator in the kidnapping plot, John Surratt, was a known Confederate courier, helping to transport mail and people across the line between Union and Confederate territory. In October of 1864, while working on his plan to abduct Lincoln, Booth traveled to Montreal, Canada, a hotbed of Confederate intrigue, where it was claimed he met with high-ranking Confederate officials stationed there. At the trial of the Lincoln conspirators, a group of witnesses gave damning testimony regarding Booth’s familiarity with members of the Confederate leadership in Canada. The belief of the federal government was that the assassin was following the directive of Confederate leaders and that they were as much to blame for the murder of Lincoln as John Wilkes Booth.

However, despite the strong belief that the Confederate government was the moving spirit of Booth’s plot, concrete evidence proving such a connection has never quite materialized. Most of the witnesses who placed Booth with high-ranking Confederate officials in Canada were later proven to have committed perjury and been bribed to provide their false testimony. No document from the Confederate government mentions Booth, nor were any documents connecting him to the Confederacy found among Booth’s papers after his crime. John Surratt denied that his foray with Booth was in any way connected with his activities as a rebel courier.

While Booth undoubtedly had flirtations with Confederates and clearly assembled a gang of Confederate sympathizers to help him in his plan, the smoking gun proving that John Wilkes Booth was acting as an authorized agent of the Confederacy remains elusive.

Even with acknowledging the lack of definitive proof, Tidwell, Hall, and Gaddy proceeded to build a circumstantial case attempting to prove the Confederacy culpable for Lincoln’s death. One piece of evidence the men pointed to revolved around a trip John Wilkes Booth took to the Parker House hotel in Boston, Massachusetts, in July of 1864.

Part of Come Retribution discusses a Confederate attempt to utilize biological warfare against the Union. Several boxes of clothing “infected” with Yellow Fever were sent to northern cities in an effort to start an outbreak of the deadly disease. Luckily, the plot proved unsuccessful as the medicinal knowledge of the day was unaware that Yellow Fever is not contagious but is spread through the bites of infected mosquitoes. Still, this attempt to poison Northern cities was a significant escalation, and the plot was discussed at the trial of the Lincoln conspirators to show how the Confederacy had been willing to commit terrible deeds to win the war.

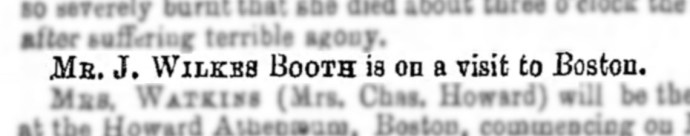

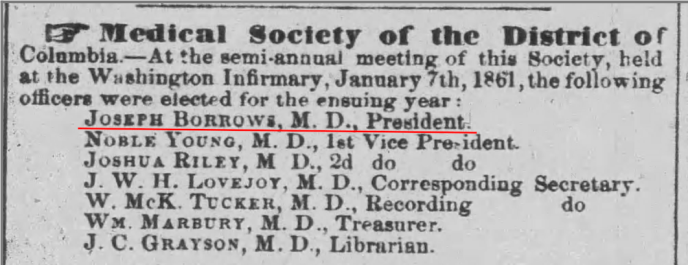

Details of the Yellow Fever plot piqued the interest of a man named Cordial Crane, who was an official of the Custom House in Boston, Massachusetts. The trunks of yellow fever clothing had made their way through the port of Boston, and one of the conspirators in the plot was said to have stayed at the Parker House hotel in Boston during the shipping process. Acting under his own initiative, Crane went and consulted the hotel register for the Parker House. While he was not able to find any evidence of the Yellow Fever conspirator in the ledger book, he did note the appearance of John Wilkes Booth’s name. I’ll let Come Retribution take it from here:

“…He [found] J. Wilkes Booth on the Parker House register for 26 July 1864 along with three men from Canada and one from Baltimore. Crane’s suspicions were aroused. He copied the entries and sent a letter dated 30 May 1865 to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. He listed the names “Charles R. Hunter, Toronto, CW [Canada West], J Wilkes Booth, A. J. Bursted, Baltimore, H. V. Clinton, Hamilton, CW, R. A. Leech, Montreal.” In his letter to Stanton, Crane wrote that he sent the “names as a remarkable circumstance that representatives from the where named places should arrive and meet at the Parker House at about the same time Harris was on his way to Halifax with his clothing.” Crane put the emphasis in his letter on “Harris” and the supposedly infected clothing. No investigation was made into the other names on the Parker House register. After all, Booth was dead and the War Department already had information about the “yellow fever plot.” Crane’s letter was filed and not followed up.

Now, more than a century later, the gathering at the Parker House can be construed differently. It has all the earmarks of a conference with an agenda. The inference is that agents of the Confederate apparatus in Canada had a need to discuss something with Booth. Capturing Lincoln? Within a few weeks Booth was in Baltimore recruiting others for just such a scheme and had closed out his Pennsylvania oil operations. The inference becomes stronger as a result of a careful search of records in Toronto, Baltimore, Hamilton, and Montreal. No trace of Hunter, Bursted, and Leech was found. The names appear to be aliases.

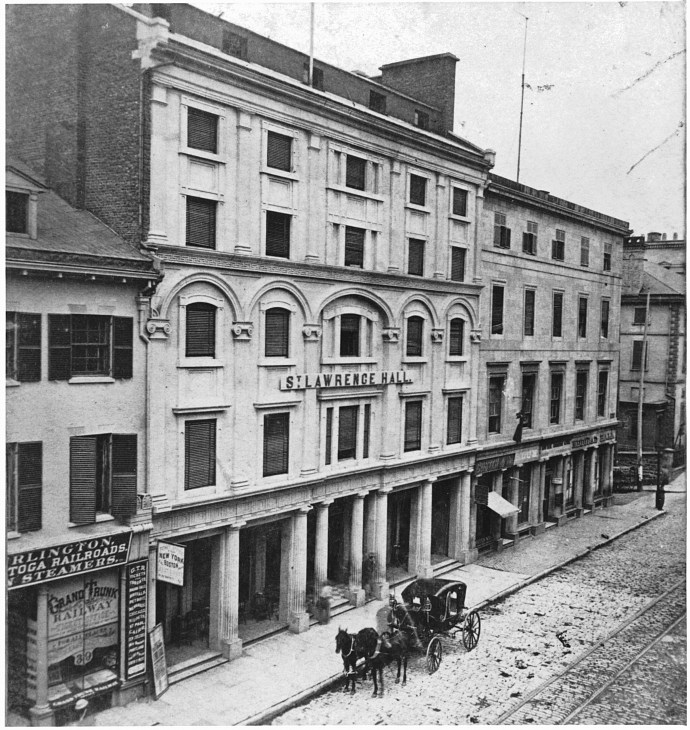

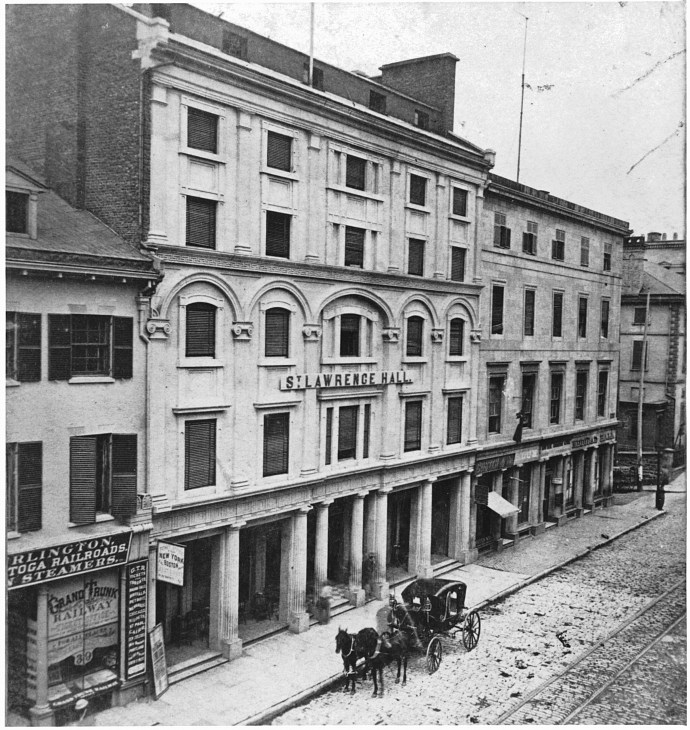

The man using the name “H. V. Clinton” did turn up in a not unexpected place. Such a man registered at the St. Lawrence Hall, Montreal, on 28 May 1864. Instead of listing himself as from Hamilton, CW, he gave his home address as St. Louis, Missouri. He was back at the St. Lawrence Hall on 24 August 1864, again entering his name on the register as “H. V. Clinton, St. Louis.” A thorough search of St. Louis records from the 1850-1870 period was made. “H. V. Clinton” was not found.”

Now this is an example of where I believe Tidwell, Hall, and Gaddy go too far astray with their suppositions and theories in hopes of proving their overall thesis. With nothing but transferred names from a hotel registry, they have concocted a scenario in which Booth engaged in a meeting with these fellow hotel guests, and that the purpose of this meeting was the actor’s recruitment into an abduction plot against the President. The main evidence of this scenario is the trio’s belief that the names used in the register are aliases, and thus, proof of the men being Confederate agents. Yet this is a laughable conclusion to make without evidence. A researcher’s inability to find more information about a person listed in a hotel registry doesn’t prove the person used an alias. Once you start down that route, you might as well put on your tinfoil hat because then every name is an alias.

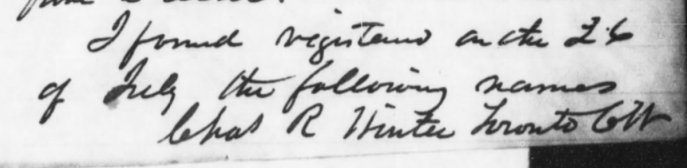

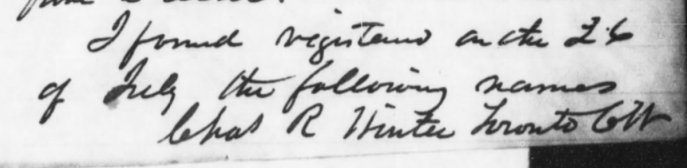

Tidwell, Hall, and Gaddy were good researchers, to be sure, but they were as capable of making mistakes and missing things as anyone. One thing that they, and other researchers since, have missed is the fact that they have transcribed one of the names from Crane’s list incorrectly. His list doesn’t include the name Charles R. Hunter, but rather the name “Chas R Winter.”

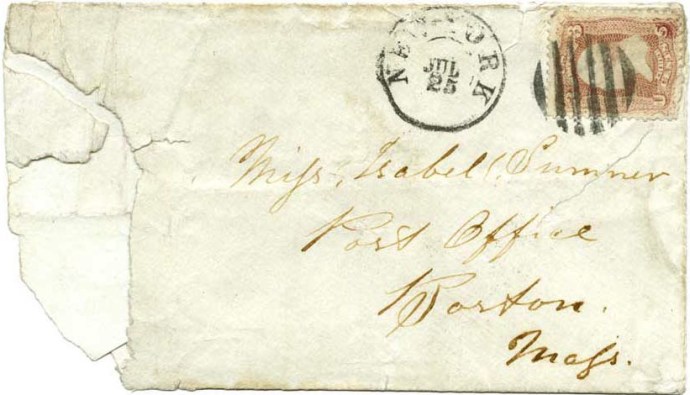

Above is the original handwritten letter that Crane sent to Edwin Stanton. A microfilmed version of the letter is contained in the Lincoln Assassination Evidence collection housed at the National Archives, and that entire collection is digitized and viewable at Fold3.com. At the bottom of the first page, Crane lists the first of five names he copied from the Parker House hotel registry dated July 26, 1864.

Now, looking at it quickly, I can understand why Tidwell, Hall, and Gaddy read this as “Charles R Hunter, Toronto CW.” The first letter of the last name certainly seems like an H with an incomplete crossbar. We’ll get to that later. Instead, look at the second letter in the last name. Tidwell, Hall, and Gaddy transcribed this letter as a “u”, but there is clearly a dot floating above it indicating the letter is actually an “i”. An “i” is also the only way that the rest of the word “-nter” would work, since a cursive “n” had two bumps and a ‘u” would steal one of these bumps to make the downstroke. William Edwards and Edward Steers, in their edited printed volume of the evidence agrees that this second letter is an “i” and they transcribe the name as “Chas R Hinter.” However, I believe the name is actually “Winter” with the “W” somewhat hastily drawn. For comparison, look at the way Crane writes Booth’s middle name.

Note how the “W” in Wilkes starts with a little flag or serif before starting the down stroke. The first letter in Charles’s last name also starts with a flag-like serif (admittedly, a somewhat smaller one). Returning to “Wilkes’ we can see how Crane’s downstroke immediately angles upwards and then falls again to make the middle of the “W.” However, rather than bringing the final stroke completely back to the top to complete the capital “W,” this final stroke is significantly shortened and connects directly into the next letter, an “i.” When I taught cursive to my third graders, I always taught them that a capital W doesn’t connect to the rest of the word, but Crane has made his own shortcut of sorts. We can see the same basic formation later on the second page when Crane writes about “the sad tragedy at Washington.” Again, the capital W starts with a decorative serif (this time it’s not connected to the main letter) and the final stroke of the W is almost non existent as it merges into the “a.” Looking back at Charles’s name we see the small flag, the downward stroke and then the start of the upward angled stroke before the line breaks. It could have been that the pen Crane was using was misbehaving, or he failed to put enough pressure during this stroke, which is why it cuts off. Still, we then have the downstroke and the significantly shortened final upstroke that goes into the “i” instead. For those who might still believe this letter is meant to be an “H,” look at the other examples of capital Hs in the letter. There is no starting serif, no upward diagonal. Crane forms the middle of his H by making a loop in his second vertical line. There is no evidence of an attempt to “loop” the downward stroke before the “i.” The name is not Charles Hunter or Charles Hinter, but Charles Winter.

While Tidwell, Hall, and Gaddy may not have been able to find a Charles R. Hunter living in Toronto, there was a Charles R. Winter who lived there. Charles Robinson Winter was born in Barnstaple, England, in 1832. His older brother immigrated to Canada in the late 1840s, and Charles eventually followed him. Charles R Winter from Toronto is included in the arrivals list for the Royal Hotel in Hamilton, Ontario, on May 17, 1864. In January 1865, he married a fellow English native turned Canadian resident, Elizabeth A. Baker, at the home of her brother in Toronto. In the 1871 and 1881 censuses, Winter is listed as an “agent” and directories specify him as a “manufacturer’s agent,” a role that would require a lot of travel. In fact, in the 1868 Toronto directory, his occupation is listed as “traveller.” Now, I can’t prove that this Charles R. Winter is the same one as the one who checked into the Parker House hotel in Boston on July 26, 1864, but I feel that this is more of a possibility than this name being an alias. Winter died in 1899 and is buried in Toronto.

The final name on Crane’s list is “R. A. Leech Montreal.” Though it’s spelled a tiny bit differently, through some research, I pretty quickly found a Robert A. Leach who resided in Montreal during this time period.

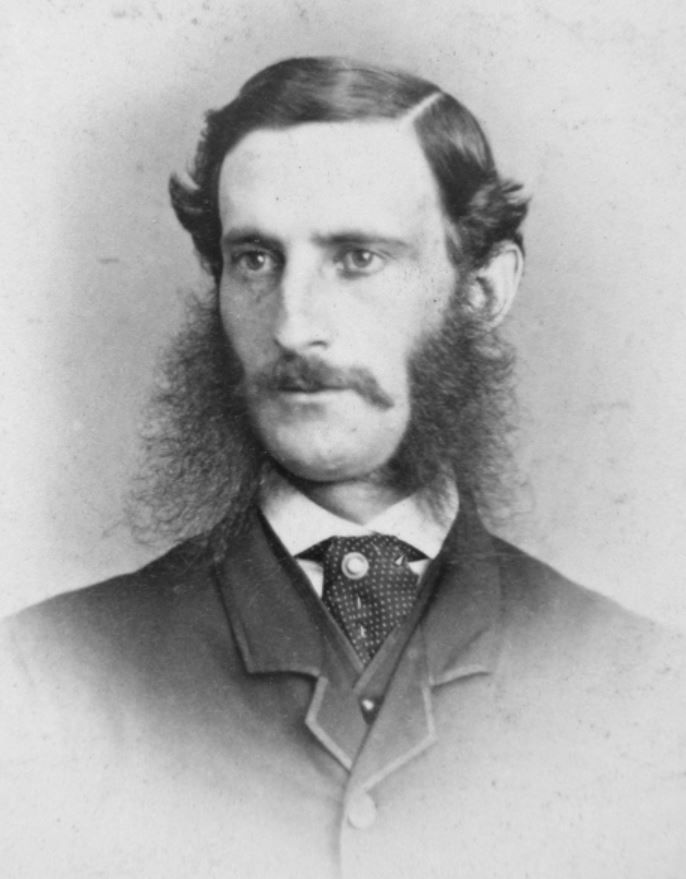

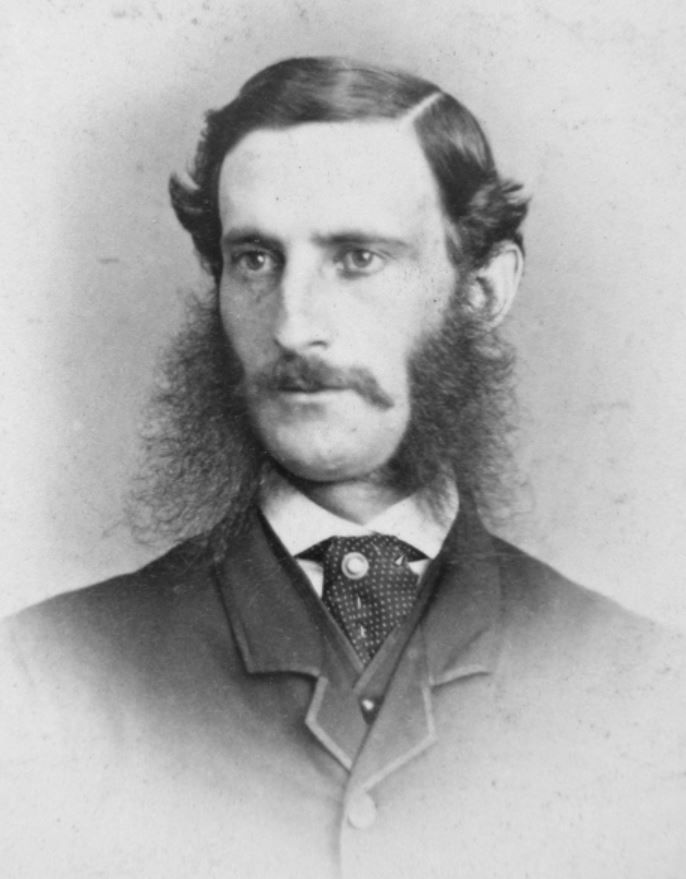

Robert A. Leach (according to an image on FindaGrave)

Robert A. Leach was a young lawyer from Montreal. He is found in the 1864 Montreal directory as the “R” in “R & D Leach, Advocates.” This was a firm he shared with his brother David. Both were the elder sons of William Turnbull Leach, the archdeacon of Montreal’s St. George Church. Robert A. Leach died from an unspecified illness in 1871 at the age of 32. He is buried in Montreal. Again, I feel the possibility that the R A Leech in Crane’s letter is more likely to have been Robert A. Leach than an alias of a Confederate agent.

Now I wish I could say that I’ve found prospective identities for each of the names on the list. While I definitely have a step up over Tidwell, Hal, and Gaddy, who worked in the pre-Internet age, the remaining two names on the list have mostly eluded my own searches.

However, it’s clear from Crane’s letter that he had a hard time deciphering the last name of the man from Baltimore. Come Retribution only provides Crane’s first guess, “A J Bursted,” but the original letter shows Crane adding “(or Rursted)” after this entry, showing his uncertainty. “Bursted” and “Rursted” are not surnames for anyone. It is unlikely a person would have used such a nonexistent last name, even as an alias. It is far more likely that Crane just couldn’t read the poor handwriting of the entry. The last name might have been Bustard, Buster, Bumstead, or something else entirely. With only the initials “A. J.” (if even those are accurate), we don’t know what first names to search. Unfortunately, we cannot go back to the original records ourselves to try our hand at deciphering these names. The original registers for the Parker House hotel during this period no longer exist. All we have is this small snapshot from Crane, which doesn’t even specify if these were the only names entered into the register on July 26, 1864. It seems unlikely that a busy metropolitan hotel like the Parker House would only gain five guests over the whole day. It seems more likely that these were the only names Crane recorded because he was looking for a connection to Canada.

The Parker House hotel in Boston

But let’s still look at “H V Clinton” of Hamilton, Canada West. This name is seemingly the linchpin of Come Retribution’s theory that the names on the list are all aliases. As they note, the name “H V Clinton” also appears on the register for the St. Lawrence Hall hotel in Montreal in 1864. That hotel was known to cater to many Confederate agents and sympathizers. It was said that the St. Lawrence Hall was the only hotel in Canada to serve mint juleps, a favored drink among the plantation South. I’ll admit that I have not been able to find an “H. V.” Clinton living in Hamilton, Ontario. However, I did find a whole family of Clintons, with different initials, who lived in the area. James H. and William Wesley Clinton were farmers who resided in the Oneida Township of Haldimand County, Ontario. Haldimand County abuts the city of Hamilton, and the distance between downtown Hamilton and the Oneida Township is about 18 miles. A resident of this rural area would likely provide their place of residence as Hamilton on a hotel register in the same way Booth regularly registered in hotels as being from Baltimore rather than Bel Air. While Booth had also lived in Baltimore as a child, once his father died in 1852, he never resided in Baltimore again. The Booths didn’t even have a home there after the 1850s. If I were to try to find John Wilkes Booth in Baltimore records during the 1860s, I would fail. In the 1860 census, the Booths are all enumerated as living in Philadelphia. During the summer of 1864, he resided with his brother Edwin in New York City. Yet, to Booth, he was “from” Baltimore, and that’s why he would sign hotel registers that way. H V Clinton from Hamilton, Ontario, might have followed the same course. There was a man named William Clinton who lived in Hamilton and worked as a saw-filer in 1863 and beyond. Granted, none of these individuals appear to match the given initials “H. V.”, but remember that we are trusting Cordial Crane that he transcribed the right letters. Regardless, there were Clintons living in and around Hamilton, Ontario, during the 1860s who could represent the man who checked into the Parker House.

What of the mysterious H.V. Clinton, who checked into the St. Lawrence Hall in Montreal in 1864? As Come Retribution notes, this Clinton wrote his place of residence as St. Louis, Missouri. He checked in on May 28, July 8, and August 24. For some reason, the Come Retribution authors neglected to mention the July 8 entry, despite their having been aware of it. On that day, H V Clinton checked in at 7:30 pm. Earlier that same day, an entire party from St. Louis had also checked in. This party was headed by “Mr and Mrs Garneau,” their two children, a nurse, and two other guests: a “Miss Withington” and a “Miss Clinton.” The Garneaus were Joseph and Mary Garneau. Joseph was a Montreal native who immigrated to the States and settled in St. Louis. There, he established a bakery that grew into one of the largest factories for baked goods in the U.S. He produced crackers in huge quantities and helped supply the Union with crackers and hardtack during the war. Mrs. Garneau’s maiden name was Withington, and the Miss Withington who joined them was her younger sister, Emily Withington. The names of this party can also be found in a newspaper article published in Buffalo, New York, on July 6. It appears that the Garneau party traveled part of the distance from St. Louis to Montreal aboard a boat called the Badger State commanded by Captain James Beckwith. The article contained a thank you to Captain Beckwith and a positive review of the journey that the boat provided. Included in the signatories of the article are the names Joseph Garneau, Mrs. Joseph Garneau, Miss E Withinton [sic], and Miss Maggie Clinton. I have been unable to determine the relationship between this Maggie Clinton and the Garneaus.

The St. Lawrence Hall hotel in Montreal

Still, the arrival of H V Clinton, also from St. Louis, to the same Montreal hotel, on the same day as the Garneau party featuring Maggie Clinton, definitely seems to be connected. In addition, Come Retribution fails to mention that when H V Clinton returned to the St. Lawrence Hall hotel on August 24, he was not alone. That time, he checked in with “Miss Kate Clinton,” also from St. Louis. The two were put in adjoining rooms. All of this makes me think there was some sort of family connection between H V, Maggie, and Kate Clinton, and that they were also somehow connected to the cracker magnate, Joseph Garneau, who was originally from Montreal.

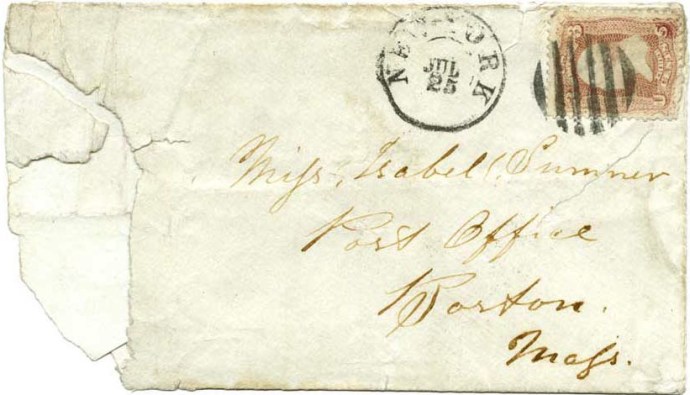

As Come Retribution mentions, searches for H V Clinton in St. Louis, Missouri, fail to provide identifying information. There were definitely Clintons living in St. Louis in 1864. So far, I have only been able to find one instance of an H V Clinton in St. Louis. It was common practice in days gone by to publish lists of unclaimed letters held by the post office in the newspaper. Many people addressed their letters with just the name of the recipient and the city or town where they resided, rather than a full street address. It was then up to the recipient to go to the post office and inquire about any letters for them to receive their mail. To illustrate this, here’s the envelope to a letter John Wilkes Booth wrote. It gives the addressee’s name but merely directs it to the post office where it would have to be picked up.

If a person did not pick up their mail from the post office after a certain period of time, postmasters would publish a list in the paper, hopefully informing the recipient that they have mail waiting for them. The name H. V. Clinton is featured on such a list in the St. Louis Globe Democrat newspaper on September 15, 1866. It’s worth noting that this date is well after the end of the Civil War. If the name H V Clinton were indeed an alias, there would have been no need to continue using it after 1865. It seems more likely that H V Clinton was a resident of St. Louis in the 1860s, albeit one that is difficult to track down.

During my research, I stumbled across other H V Clintons in the 1860s that could possibly be the same person, but their connection to St. Louis is unproven. There was an H V Clinton living in Carroll Parish, Louisiana, through the 1860s. A H V Clinton and his wife from Indiana visited Newport, Rhode Island, in 1862. Henry V. Clinton, residing in Newport, advertised for a nanny to accompany him and his young son on a year-long trip to Europe in 1864. There’s no way to prove or disprove that any of these are the same H V Clinton.

In the same way, we cannot prove that the H V Clinton from Hamilton, Ontario, who signed the Parker House hotel registry in Boston on July 26, 1864, is the same H V Clinton from St. Louis, Missouri, that thrice signed the St. Lawrence Hall register in Montreal in May, July, and August of 1864. The difficulty in finding either of these men does not prove they are the same person or, even more, that they were an alias for a Confederate agent who subsequently recruited Booth into the plot to kidnap Lincoln.

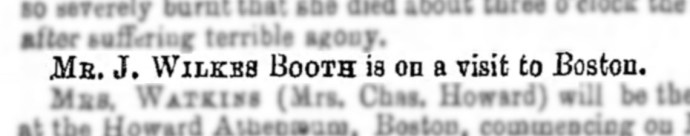

In the credit of Tidwell, Hall, and Gaddy, when they wrote Come Retribution, they were understandably intrigued by the fact that Booth made a seemingly random visit to Boston in the summer of 1864. In June of that year, he had been tending to his failing oil investments in Pennsylvania before arriving and spending weeks with his family in New York City and in New London, Connecticut. This register entry of a trip to Boston was a mystery, and, following Cordial Crane’s suspicions, the trio made a conspiracy out of it.

However, just about a month before Come Retribution was published, a new and exciting discovery was made. Six letters written by the assassin between June 7 and the end of August 1864 were made known to historians. Booth had written the letters to a 16-year-old Boston girl by the name of Isabel Sumner. The actor had likely met the girl during his long engagement in Boston earlier that spring. From the tone and content of these letters it is clear that Booth was smitten with the young woman, so much so that he even gifted her a pearl ring with the inscription “J.W.B. to I.S.” Though it does not appear that their romance lasted beyond the summer, young Ms. Sumner retained this cache of letters, the ring, and photographs of the actor, even after he murdered the President. These items were passed down through members of her family until her descendants revealed them and sold the lot in 1988 to collector Louise Taper. James O. Hall, when in the process of helping to facilitate the sale of the letters to Taper, even wrote to the Sumner descendant offering to send a copy of his soon-to-be-published book, Come Retribution. Had the Sumner letters been known a year earlier, the contents may have caused Hall to see Booth’s Boston trip in a less conspiratorial light.

Isabel Sumner

On July 24, 1864, Booth wrote to Isabel Sumner from his brother’s home in New York City. That letter was sealed in the envelope previously shown above. The smitten Booth apologized to Isabel for coming on so strong with his many love letters and feared he had scared her off. He apologized for his intensity and vowed not to write her another letter until he heard from her. Yet, despite this vow, it’s clear Booth was unwilling to wait for a response. He ended his letter with, “Remember, dear friend not to let anyone see my letters. I will come at once to Boston.” Two days after writing this letter, Booth checked into the Parker House hotel in Boston.

Seen in its proper context, there is no mystery regarding Booth’s visit to Boston in July of 1864. The man was clearly smitten with 16-year-old Isabel Sumner and traveled from New York to Boston to see her. His own written words betray his purpose. His trip to Boston was not of a conspiratorial nature, but one of desire.

In the years since Come Retribution was published, several authors have taken up Tidwell, Hall, and Gaddy’s thesis, transforming what the trio presented as couched theories into near certainties. The late John Fazio, author of Decapitating the Union, was the greatest master of this. In his section about Booth’s visit to the Parker House he stated uneqivialy (and without evidence) that Booth, “met with three Confederate agents from Canada and one from Baltimore” and that “this meeting was the first, or at least one of the first, that John had with Confederate agents and that many more followed.” Yet, as can be seen, there is no evidence that Booth took part in a Confederate conference at the Parker House hotel in Boston. The underlying “support” for this is that some of the men who also checked into the hotel on this date were from Canada, and researchers of the past couldn’t find out more about them.

As I stated at the beginning of the post, John Wilkes Booth did have some legitimate and intriguing connections with members of the Confederate underground. But we must also remember that much of this underground was not the same as the official Confederate Secret Service, which enacted authorized missions. Confederate sympathizers often acted in the same way as modern terrorist cells. They had the same ultimate goal to help the Confederacy and win the war, but not every action completed by these groups was controlled by or even known to the Confederate government.

Ultimately, I believe that Booth was speaking honestly when he closed his manifesto for the kidnapping plot, identifying himself as “A Confederate doing duty upon his own responsibility, J. Wilkes Booth.” But even those who believe that the Confederate government may have had a hand in Booth’s plots against Lincoln, it is important to be realistic about the evidence supporting this. There is nothing to support the idea that John Wilkes Booth met with Confederate agents at the Parker House hotel in July 1864.

If you found this post interesting and want to support my research and writing, please consider joining my Patreon page. For just $3 or more a month, you get access to a weekly newsletter that keeps you up to date on all things Lincoln assassination-related. For $7 or more a month, you also get access to exclusive fortnightly posts delving into the history of artifacts relating to the assassination story, and for $15 or more a month, you get monthly videos from me where I share new research discoveries and answer your questions about this history. The contributions of patrons help cover my research subscriptions and associated website costs. For example, the All Access Membership subscription to Ancestry.com (which was needed to consult Canadian and other international records in the writing of this post) costs about $500 a year, so every little bit helps. Click here or on the icon below to learn more about my Patreon.

Recent Comments