The collection of the National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM) contains several objects relating to Presidential health and care. In regards to the Lincoln assassination, the museum contains items extracted from both the President and his assassin during their subsequent autopsies. Booth’s vertebrae and a piece of his spinal cord, through which Boston Corbett’s bullet passed, are housed in this collection. From Lincoln’s autopsy, the museum has pieces of Lincoln’s skull, the bullet that took his life, and some hair clippings taken by the doctors and surgeons as mementoes. As was previously written, the collection was once housed at Ford’s Theatre from 1865 – 1887 when it was called the Army Medical Museum. During that time at Ford’s however, the Lincoln relics were not part of the collection, only Booth’s pieces were there. In fact, the bullet that killed Lincoln was entered as an official exhibit during the Conspiracy Trial and it, along with the skull pieces, were housed with the other evidence in the office of the Judge Advocate General. In 1940, the exhibits were donated to the Lincoln Museum (Ford’s) who then gave the bullet and pieces of Lincoln to the Medical Museum. So while pieces of Lincoln and Booth both returned to the venue of their last living meeting, it was not at the same time.

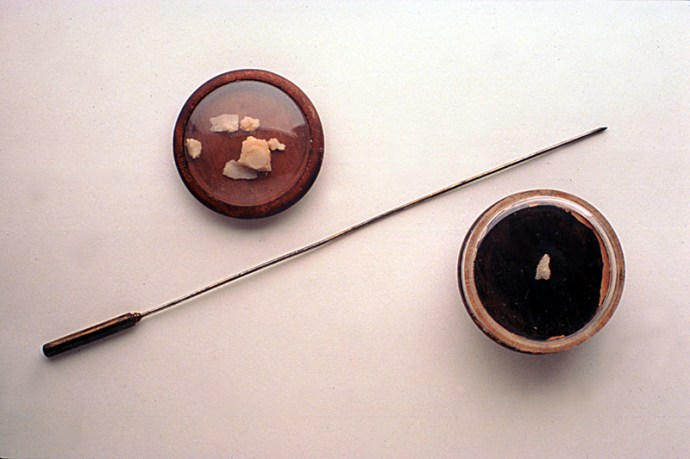

In addition to the bullet and the skull fragments, the National Museum of Health and Medicine also has a rather unassuming instrument housed with these Lincoln relics: a long, medical probe:

This probe has a specific name and a specific function. Called a Nélaton probe (or Nélaton’s probe) it was used by the doctors during Lincoln’s final night to ascertain the depth and path of the bullet in Lincoln’s head. Before delving into that, however, let’s look at the history behind this medical tool.

In 1862, Italian general Giuseppe Garibaldi, was shot while trying to take control over the city of Rome. At that time, Italy had just completed a massive unification to create one kingdom. This kingdom of Italy later became the republic of Italy as we know it now. However, as of 1862, several cities in Italy did not accept unification and Rome was one of them. Tired of waiting for them to come around, General Garibaldi decided to raise a volunteer force to take the city of Rome. The Battle of Aspromonte, as it was called was fought between Garibaldi’s men and the Royal Army of Italy on August 29th, 1862. Both sides were hesitant to harm the other as they were countrymen and Garibaldi was well liked and supported by the people of Italy. When the Royal Army “attacked” Garibaldi’s forces, he ordered his forces not to fire on their brothers. One part of his army did attack though, and during the fire fight, Garibaldi was hit three times. The battle lasted less than ten minutes with only 15 combined casualties. Garibaldi and the rest of his volunteers were arrested and imprisoned.

While imprisoned, Garbaldi was still given the respect and medical treatment he deserved. Two of the three shots Garibaldi received were to the hip and proved easily treatable. The third shot hit Garibaldi’s right ankle, just a little above and in front of what we would consider the “ankle bone” (scientifically, it was his internal malleolus). This wound pained him greatly. When he was on the battlefield, a surgeon had made an incision on the opposite side of the wound when he felt swelling but found nothing inside of it. A few days after the battle, Garibaldi was re-examined by more than half a dozen doctors who all believed, save one, that the bullet was no longer in his ankle. Meanwhile, in England, supporters of Garibaldi in the medical field took it upon themselves to see if they could help the general. In an extremely presumptuous way, the English doctors elected that Dr. Richard Partridge, professor at King’s college, should travel to England and check on Garibaldi’s wound and treatment. When Dr. Partridge arrived on September 16th, he examined Garibaldi himself, and came to the same conclusion of the Italian physicians: the ball was no longer in his ankle. He returned back to England and guaranteed his colleagues and the press that, while Garibaldi was still in considerable pain, it was not caused by a bullet being lodged in his ankle. Dr. Partridge believed his condition would improve in time.

After five weeks, though, no improvement was noted and Garibaldi was still in quite a deal of pain. This time, the Italian doctors reached out. They sent for Auguste Nélaton, a Parisian professor of surgery. He arrived on October 28th and examined Garibaldi himself. After inserting a normal probe into the wound, he was convinced that the bullet was still in there. The Italian doctors did not concur, citing Dr. Partridge’s agreement of their initial assessment. So, Dr. Partridge returned. Soon, Garibaldi’s sick room became an international conference with the Italian doctors, the Frenchman Nélaton, the Englishman Partridge, and even a Russian physician all prodding and poking General Garibaldi. Dr. Partridge actually changed his mind and started believing that the bullet was still in the general’s ankle. Nélaton, believing amputation to be unnecessary, ordered that the wound entrance be widen with sponges so that the bullet could be removed in time. While the Italian doctors followed this idea, they were still unconvinced that there was a bullet in Garibaldi, and were getting sick of all these foreigners going back and forth on the matter.

When Nélaton returned to France, he started working on a way to prove that there was a bullet in Garibaldi. The problem was that it was impossible for a physician of the time to identify the hard substance met by a probe in a wound. It could be normal bone or a foreign substance like a bullet. The bulk of the Italian doctors believed their probes continually hit the normal bone structure of the ankle, while Nélaton thought it was a bullet. Nélaton began constructing a new probe for his purposes. In the end, his probe was ingenious in its simplicity. At the tip of a normal medical probe he attached an unglazed porcelain tip. When the porcelain touched bone inside a wound, the probe would be unaffected. When it rubbed against the lead of a bullet however, the tip would become marked identifying it as a foreign substance.

Nélaton quickly sent his new instrument to the doctors in Italy. After using it to confirm Nélaton’s diagnosis that the bullet was, in fact, still in Garibaldi’s ankle, the Italian physicians were able to successfully remove it on November 22nd. Shortly thereafter General Garibaldi sent a letter to Auguste Nélaton offering his love, gratitude, and thanks.

Nélaton’s probes proved wonderfully efficient. They started to be produced on mass and were shipped all over the world. They quickly became an instrument of necessity for any military surgeon and found a market in the surgeons fighting on both sides of the American Civil War. They continued to be used into the 1900’s before they were essentially replaced by the advent of less intrusive devices like the X-ray.

Let’s return now to the night of April 14th, 1865. Lincoln was taken to the Petersen House across the street from Ford’s after being shot. There, he was attended to by several doctors including the Surgeon General Joseph Barnes and the first responder, Dr. Charles Leale. At first, the doctors introduced regular, silver probes into Lincoln’s wound. However, like in Garibaldi’s case, they were unsure if the solid mass they encountered was the bullet or a piece of Lincoln’s skull. A steward was then sent for a Nélaton probe. From Dr. Leale’s account we can learn how they used the device:

“About 2 AM the Hospital Steward who had been sent for a Nelatons probe, arrived and an examination was made by the Surgeon General, who introduced it to a distance of about 2 ½ inches, when it came in contact with a foreign substance, which laid across the track of the ball.This being easily passed the probe was introduced several inches further, when it again touched a hard substance, which was at first supposed to be the ball, but as the bulb of the probe on its withdrawal did not indicate the mark of lead, it was generally thought to be another piece of loose bone. The probe was introduced a second time and the ball was supposed to be distinctively felt by the Surgeon General, Surgeon Crane and Dr. Stone.”

Using Nélaton’s probe, the doctors established that the bullet was above and behind Lincoln’s right eye. Between its use in the early hours of April 15th and today, the Nélaton probe used by the doctors on Lincoln has lost the porcelain tip that marked the bullet.

While the first person to utilize Auguste Nélaton’s invention made a full recovery because of it, it was well established before the probe was introduced in Lincoln’s case that he was beyond help. The Nélaton probe did not change Lincoln’s medical prognosis as it did for Garibaldi, but it is still a historically relevant artifact. Its inclusion in the collection of the National Museum of Health and Medicine is so that it can be a testament to the devotion of the doctors who cared for President Lincoln. Despite the hopelessness of his situation, doctors like Barnes, Leale, Taft, and others, did all in their power to aid and comfort the fallen President.

References:

National Museum of Health and Medicine

The details regarding Auguste Nélaton’s invention came from this essay from the National Institute of Health

Dr. Leale’s account

American Brutus by Michael Kauffman

Recent Comments