Ford’s Theatre was not the only theatre in Washington, D.C. visited by President Lincoln and his family. Here are some interesting facts about the National Theatre owned by Leonard Grover.

The rivalry between the Ford and Grover

There had been a friendly rivalry between Leonard Grover and John T. Ford ever since Ford opened his first theatre in Washington in 1861. The huge increase in population in Washington D.C. during the Civil War allowed both theatres, and their owners, to prosper. Still, the two men attempted to one up each other in their attempts to get a bigger piece of the pie. After the burning of Ford’s old theatre, he rebuilt, creating a smaller, but far more luxurious and comfortable theatre. This was at odds with Grover’s, whose theatre which was described as, “an ice vault in winter, and a sweatbox in summer”. Grover advertised his theatre as the capital’s only “Union” playhouse, highlighting John Ford’s more “Secesh” sentiments. Both houses had vied for Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln’s attendance on April 14th, 1865, but it was Ford’s Theatre, with Laura Keene’s Our American Cousin, that won the honor.

Tad Lincoln Attended Grover’s on April 14th

Unlike his parents, Tad Lincoln was more interested in seeing “Aladdin” at Grover’s Theatre on April 14th, 1865. It was there that poor Tad learned of his father’s assassination. Another individual who was attending Grover’s that night was Corporal James Tanner, a wounded Union veteran whose training in shorthand would prove invaluable later. Tanner described the moment when the news of Lincoln’s assassination reached the theatre:

“While sitting there witnessing the play about ten o’clock or rather a little after, the entrance door was thrown open and a man exclaimed, “President Lincoln is assassinated in his private box at Ford’s!” Instantly all was excitement and a terrible rush commenced and someone cried out, “Sit down, it is a ruse of the pickpockets.” The audience generally agreed to this, for the most of them sat down, and the play went on; soon, however, a gentleman came out from behind the scenes and informed us that the sad news was too true. We instantly dispersed.”

Tad, quite distraught over the shocking news about his father, was quickly removed from Grover’s and taken to the White House. White House doorkeeper, Thomas Pendel, recalled what happened when Tad returned home:

“Poor little Tad returned from the National Theatre and entered through the east door of the basement of the White House. He came up the stairway and ran to me, while I was in the main vestibule, standing at the window, and before he got to me he burst out crying, “O Tom Pen! Tom Pen! They have killed papa dead. They’ve killed papa dead!” and burst out crying again.

I put my arm around him and drew him up to me, and tried to pacify him as best I could. I tried to divert his attention to other things, but every now and then he would burst out crying again, and repeat over and over, “Oh, they’ve killed papa dead! They’ve killed papa dead!”

At nearly twelve o’clock that night I got Tad somewhat pacified, and took him into the President’s room, which is in the southwest portion of the building. I turned down the cover of his little bed, and he undressed and got in. I covered him up and laid down beside him, put my arm around him, and talked to him until he fell into a sound sleep.”

Leonard Grover Wasn’t in Town

At the time of the assassination neither John T. Ford or Leonard Grover, were at their namesake theatres. Each man owned or leased other theatres in other cities and were tending to business elsewhere. John T. Ford was in Richmond at the time of the assassination and Leonard Grover was in New York. After the news had reached Grover’s Theatre and the building had emptied, Charles Dwight Hess, the manager of Grover’s Theatre, sent a telegram to Leonard Grover in New York. Grover later recalled:

“On that eventful day I was in New York, busily getting ready for my approaching Easter season of opera at the Academy of Music. I had passed a laborious day and retired an early hour, at the old Metropolitan Hotel. I was soundly sleeping when a sharp rap at the door awoke me, and some one called, ”Mr. Grover, here’s a telegram for you.” Thinking it was the usual message from one of the theaters (for I was then managing a Philadelphia theater as well) which would simply convey the amount of the receipts of the house, I called back: “Stick it under the door.” But the rapping continued with vigor, and there were calls, ”Mr. Grover, Mr. Grover, please come to the door!”

I arose, hastily opened the door, when the light disclosed the long hall compactly crowded with people. Naturally, I was astonished. A message was handed to me with the request: “Please open that telegram and tell us if it’s true.” I opened it and read:

“President Lincoln shot to-night at Ford’s Theatre. Thank God it wasn’t ours. C. D. Hess.”

What follows is a copy of the Grover’s Theatre playbill that was used for the April 14th, performance of “Aladdin”.

The handwritten text at the top reads, “The night President Lincoln was shot at Fords Theatre. “Tad” Lincoln with his Tutor was with me at -“. Though the playbill is credited as belonging to Leonard Grover, we know Grover was not at his theatre at the time of the assassination. It is likely that this playbill was actually owned by Charles D. Hess, the manager of Grover’s who as present at theatre and shared the news with the audience.

The Assassination could have been at Grover’s Theatre

In April of 1909, two articles were published in Century Magazine which theorized that Lincoln still would have been assassinated even if he had attended Grover’s Theatre that night instead of Ford’s. For a wonderful recounting of this theory, please visit the corresponding page on Roger Norton’s Lincoln Assassination Research Site.

Booth carried Aladdin with him

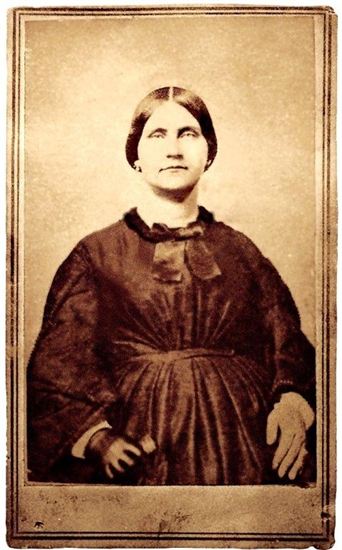

When John Wilkes Booth was cornered and killed at the Garrett farm, the detectives thoroughly searched his person, removing any papers and objects they could find. Inside his small memorandum book (better known as his diary), they found five photographs. One of the photographs was of this woman:

Her name is Effie Germon and she was an actress friend of John Wilkes Booth. If you look at the playbill for Grover’s production of “Aladdin” you can find her name. She was the star of the night, portraying the eponymous Aladdin.

References:

Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination by Thomas Bogar

Thirty-Six Years in the White House by Thomas Pendel

“What if the Lincolns had attended the play at Grover’s Theatre” by Roger Norton

Lincoln’s Interest in the Theatre by Leonard Grover

“Lincoln and Wilkes Booth as Seen on the Day of the Assassination” by M. Helen Palmes Moss as printed in the Century Magazine (April, 1909).

Recent Comments