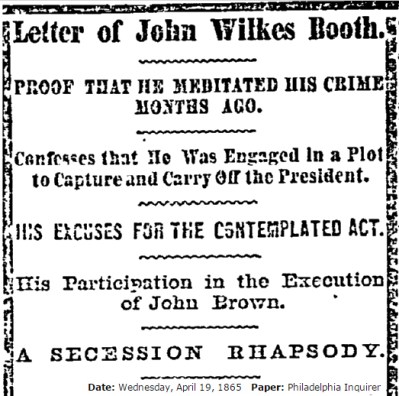

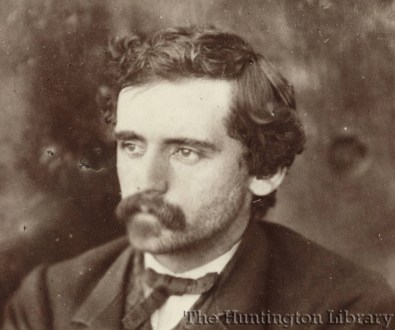

On this date in 1865, the Philadelphia Inquirer published a telling letter written by John Wilkes Booth, the recent assassin of President Lincoln.

The letter is known to readers of the Lincoln assassination story as John Wilkes Booth’s, “To Whom it May Concern” letter. Its title is derived from the letter’s greeting which was appropriated by Booth from a letter written by Lincoln in July of 1864. At that time, a small delegation of “peace emissaries” representing the Confederacy had approached the Union government under the guise of facilitating a cessation of hostilities and possible re-unification of the nation under the condition that they be allowed to continue the practice of slavery. It was a difficult period in the war and Lincoln himself knew his chance of winning re-election later that year was slim. Knowing that Lincoln would never agree to their terms, the so-called “Niagara Falls peace conference” was a piece of propaganda for the Confederacy, which was more aimed to further diminish Lincoln’s approval and chance of re-election. Lincoln was likely well aware of conference’s true purpose and wrote to the “peace emissaries” that any discussion of peace must include the “abandonment of slavery”.

Knowing that his position would be viewed and lamented as stubbornness by the Confederacy and by the Democrats running against him, Lincoln decided to add further insult to injury by refusing to address the emissaries by name. Instead, Lincoln wrote his note “To Whom it May Concern,” diminishing the importance and respectability of the so-called “peace emissaries.” John Wilkes Booth subsequently used this somewhat insulting address in his own explanatory letter that follows.

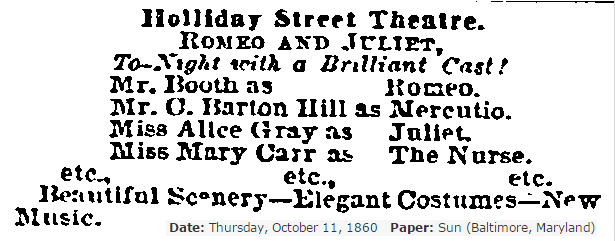

The letter was published due to the efforts of Booth’s brother-in-law, John Sleeper Clarke. Following the assassination of Lincoln, Clarke and his wife, Asia Booth, recalled that John Wilkes had left a package of papers in the safe of their home in Philadelphia. Upon opening the package they found this letter, another addressed to his mother, Mary Ann Booth, and some oil stocks. As more and more Booths arrived at the Clarkes’ home (Mary Ann came from New York very soon after hearing the tragic news in order to comfort Asia, who was pregnant, and Junius Jr. arrived from an acting engagement in Cincinnati to be with the family), John Sleeper thought that the letters would be of help in proving the family’s innocence as to John’s plan. Clarke had copies made of both the To Whom it May Concern letter and the one addressed to Mrs. Booth. Then, accompanied by a member of the Philadelphia press corps, Clarke went to the office of William Millward, the Provost Marshal of Philadelphia.

Clarke asked the Marshal for permission to publish the letters and the circumstances surrounding their discovery in order to demonstrate that the family had no foreknowledge of John Wilkes’ crime. Millward approved the publication of the To Whom it May Concern letter for the next day but not the letter that John Wilkes wrote to his mother. Millward did not want anything published that might garner sympathy for the assassin. This was a let down to Clarke, as Booth’s letter to his mother more effectively demonstrated how completely unaware the family was as to John Wilkes’ intentions. While the To Whom it May Concern letter was published, it did not assuage the suspicion on the Booth family. Shortly after the letter was published, both John Sleeper Clarke and Junius Brutus Booth, Jr. were arrested and taken down to Washington, D.C. The youngest Booth, Joseph, would also be arrested leaving Edwin as the only male Booth not to be locked up. This series of events greatly bothered Clarke, who would complain about his improper treatment and the favored treatment of Edwin for the rest of his days. The assassination and the events that followed it marked the beginning of John Sleeper Clarke rejecting all things Booth, including his wife, Asia, whom he would grow to loathe.

Though not dated besides the year, Booth’s letter was likely written just following Lincoln’s miraculous re-election in November of 1864. The letter lays out John Wilkes Booth’s political and ideological beliefs and provides his reasons for his plan to abduct President Lincoln. Booth had started, sort of halfheartedly at first, to assemble a crew of conspirators in the summer of 1864 with the idea of abducting the President and taking him South. In this manner, Booth hoped to use Lincoln as a hostage to reinstate the prisoner exchange program between the Union and the Confederacy. This idea took on an increased importance in Booth’s mind after Lincoln’s surprise re-election on November 8, 1864. Immediately following this date, John Wilkes Booth began acting more in earnest and less than a week after the election, he was in Southern Maryland scouting the area and looking for others who might help him in his plot.

This letter, therefore, was written right at the beginning of Booth’s plot to abduct the President. It contains perhaps the most honest look into the mind and thoughts of John Wilkes Booth. In less than six months after this letter was written, the same motivations that led Booth to consider abduction, led him to assassinate Abraham Lincoln.

My Dear Sir 1864.

You may use this, as you think best. But as some, may wish to know the when, the who, and the why, and as I know not, how, to direct, I give it (in the words of your master)

“To whom it may concern”

Right, or wrong, God, judge me, not man. For be my motive good or bad, of one thing I am sure, the lasting condemnation of the North.

I love peace more than life. Have loved the Union beyond expression. For four years have I waited, hoped, and prayed, for the dark clouds to break, and for the restoration of our former sunshine. To wait longer, would be a crime. All hope for peace is dead. My prayers have proved as idle as my hopes. ‘God’s’ will be done: I go to see, and share the bitter end.

I have ever held the South were right. The very nomination of Abraham Lincoln four years ago, spoke plainly – war – war upon Southern rights and institutions, his election proved it. “Await an overt act.” Yes till you are bound and plundered. What folly. The South were wise. Who thinks of argument and patience when the finger of his enemy presses on the trigger. In a foreign war, I too could

say, “Country right or wrong”, but in a struggle such as ours (where the brother tries to pierce the brothers heart) for God’s sake choose the right. When a country such as ours like this, spurns justice from her side, she forfeits the allegiance of every honest freeman, and should leave him untrammeled by any fealty soever, to act, as his conscience may approve.

People of the North, to hate tyranny to love liberty and justice, to strike at wrong and oppression, was the teaching of our fathers. The study of our early history will not let me forget it. And may it never.

This country was formed for the white not for the black man. And looking upon African slavery from the same stand-point, held by those noble framers of our Constitution, I for one, have ever considered it, one of the greatest blessings (both for themselves and us,) that God ever bestowed upon a favored nation. Witness heretofore our wealth and power, witness their elevation in happiness and enlightenment above their race, elsewhere. I have lived among it most of my life and have seen less harsh treatment from master to man, than I have beheld in the North from father to son. Yet Heaven

knows no one would be willing to do, more for the negro race than I. Could I but see a way to still better their condition. But Lincoln’s policy is only preparing the way, for their total annihilation. The South are not, nor have they been, fighting for the continuance of slavery, the first battle of Bull-run did away with that idea. Their causes since for war, have been as noble, and greater far than those that urged our fathers on. Even should we allow, they were wrong at the beginning of this contest, cruelty and injustice, have made the wrong become the right. And they stand now (before the wonder and admiration of the world,) as a noble band of patriotic heroes. Hereafter, reading of their deeds, Thermopylae will be forgotten.

When I aided in the capture and the g execution of John Brown, (who was a murderer on our Western Border, and who was fairly tried and convicted, – before an impartial judge & jury – of treason, – and who by the way has since been made a God – I was proud of my little share in the transaction, for I deemed it my duty and that I was helping our common country to perform an act of justice. But what was a crime in poor John Brown, is now considered (by themselves) as the greatest and only virtue, of the whole

Republican party. Strange transmigration. Vice to become a virtue. Simply because more indulge in it. I thought then, as now, that the abolitionists, were the only traitors in the land, and that the entire party deserved the fate of poor old Brown. Not because they wish to abolish slavery, but on account of the means they have ever used endeavored to use, to effect that abolition. If Brown were living, I doubt if he himself would set slavery, against the Union. Most, in or many, in the North do, And openly curse the Union, if the South are to return and retain a single right guaranteed them by every tie which we once revered as sacred. The south can make no choice. It is either extermination, or slavery for themselves, (worse than death) to draw from. I would know my choice.

I have, also, studied hard to discover upon what grounds, the rights of a state to secede have been denied, when our very name (United States) and the Declaration of Independence, both provide for secession. But there is no time for words. I write in haste. I know how foolish I shall be deemed, for undertaking such a step, as this, where on the one side, I have many friends, and everything to make me happy. Where my profession alone has gained me an income of more than twenty thousand dollars a year. And where my great personal ambition in my profession has such a great field for labor. On the other hand- the south have

never bestowed upon me one kind word. A place now, where I have no friends, except beneath the sod. A place where I must become either become a private soldier, or a beggar. To give up all of the former for the latter, besides my mother and sisters whom I love so dearly, (although they so widely differ with me in opinion) seems insane. But God is my judge. I love justice, more than I do a country, that disowns it. More than fame and wealth. More – (Heaven pardon me if wrong) more than a happy home. I have never been upon a battlefield, but O my countrymen, could you all but see the reality or effects of this horrid war, as I have seen them (in every State, save Virginia) I know you would think like me. And would pray the Almighty to create in the Northern mind a sense of right and justice, (even should it possess no seasoning of mercy), and that he would dry up this sea of blood between us, – which is daily growing wider.

Alas, poor country, is, she to meet her threatened doom. Four years ago I would have given a thousand lives to see her remain, (as I had always known her) powerful and unbroken. And even now I would hold my life as naught, to see her what she was. O my friends if the fearful scenes of the past four years had never been enacted, or if what had been, had been but a frightful dream, from which we could now awake, with what overflowing hearts could we bless our God and pray for his continued favor. How I have loved the old flag can never, now, be known. A few years since and

the entire world could boast of none so pure and spotless. But I have of late been seeing and hearing of the bloody deeds of which she has been made, the emblem, and would shudder to think how changed she had grown. O How I have longed to see her break from the mist of blood and death that now circles round her folds, spoiling her beauty and tarnishing her honor. But no, day by day has she been draged deeper and deeper into cruelty and oppression, till now (in my eyes) her once bright-red stripes look like bloody gashes on the face of Heaven. I look now upon my early admiration of her glories as a dream. My love, (as things stand to day,) is for the South alone. Nor, do I deem it a dishonor, in attempting to make for her a prisoner of this man, to whom she owes so much of misery. If success attends me, I go penniless to her side. They say she has found that “last ditch” which the North have so long derided, and been endeavoring to force her in, forgetting they are our brothers, and that its impolitic to goad an enemy to madness. Should I reach her in safety and find it true, I will proudly beg permission to triumph or die in that same “ditch” by her side.

A Confederate, at present doing duty upon his own responsibility

J WilkesBooth

References:

“Right or Wrong, God Judge Me” : The Writings of John Wilkes Booth edited by John Rhodehamel and Louise Taper

NARA

Speaker: Dave Taylor

Speaker: Dave Taylor

Recent Comments