A half mile from Colton’s Point, Maryland, located in the Potomac River, lies St. Clement’s Island.

St. Clement’s Island is the site of the first landing of European settlers in Maryland. The landing occurred on March 25, 1634, when the 150 or so colonists aboard the ships The Ark and The Dove made landfall here having departed England four months earlier. St. Clement’s is, essentially, Maryland’s birthplace and the anniversary of the landing, March 25, is a state holiday known as Maryland Day.

In a few days, most of the colonists would move off of St. Clement’s Island, after having negotiated with the Yaocomico Native American tribe to create a permanent settlement on the mainland. That settlement would become St. Mary’s City, the first capital of Maryland.

During the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, the British captured St. Clement’s Island using it as a base for their operations. It was known then as Blackistone Island. The Blackistone family had inherited the island in 1669 and continued to own it until 1831. In 1848, the U.S. Congress appropriated $3,500 to build a lighthouse on the island, which was finally completed in 1851.

During the Civil War, the lighthouse became a target for the Confederacy. On the night of May 19, 1864, Confederate Captain John W. Goldsmith and his men landed on the island. It was Goldsmith’s intention to dynamite the lighthouse. The keeper of the lighthouse, Jerome McWilliams, begged the Captain not to destroy the building as his wife was pregnant and her life would be in danger if they had to go back to the mainland before the baby came. Goldsmith was a St. Mary’s county native who had crossed the Potomac to fight for the Confederacy and he knew McWilliams. In sympathy to McWilliams’ circumstances, instead of destroying the building Goldsmith destroyed the lighthouse’s lens and lamp, and took all of the oil. Union troops eventually were able to repair the light and stationed a unit of guardsmen on the island.

The aborted destruction of the lighthouse on St. Clement’s was not the only Civil War era event to happen near the island. A largely forgotten naval incident also occurred there during the night of April 23 and 24, 1865. This tragedy has a connection to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the search for his assassin.

The incident involves two steamer ships, the USS Massachusetts and the Black Diamond. The Massachusetts was a steam ship built in Boston in 1860. She was purchased by the U.S. Navy in May of 1861 and became the USS Massachusetts. During the Civil War, the Massachusetts was involved in enforcing the blockade of Confederacy and later worked as a supply carrier between the Northern ports and the other blockading forces.

An engraving from Harper’s Weekly showing the naval forces at Ship Island, Louisiana. The Massachusetts is the ship on the far right.

On April 23, 1865, the Massachusetts was assigned the task of ferrying Union troops from Alexandria to Norfolk, Virginia. At 5 o’clock p.m., about 400 men boarded the Massachusetts at Alexandria, with one soldier recalling later that the boat was “unfit to carry more than half the number she had on board”. The troops on board had lived through the darkest parts of the war. There were men on the Massachusetts who had survived the deadliest day in American history at the battle of Antietam. Many had been prisoners of war in the horrible prison camps of North Carolina and Georgia. Too many had witnessed their comrades perish at Andersonville prison. These men had been through the worst circumstances and had managed to survive.

As the Massachusetts steamed on one soldier remembered, “We glided along down the river very nicely until a little after dark, when a strong wind began to blow and the river became very rough…” They were nearing St. Clement’s Island.

The Black Diamond was an iron hull steam propeller canal boat built in 1842. At the time of the Civil War, the Black Diamond was being chartered by the U.S. Quartermaster Department. She regularly transported coal between Washington, D.C. and Alexandria, which was a Union occupied city. Her crew consisted of men from the Alexandria fire department.

After the assassination of President Lincoln on April 14, 1865, the Black Diamond was assigned picket duty on the Potomac River. Her job was to patrol the Potomac, keeping an eye out for the assassin, John Wilkes Booth, if he attempted to cross the river. On the night of April 23, the world was unaware that Booth and his conspirator David Herold had already crossed the Potomac and were that night sleeping in the cabin of William Lucas in King George County, Virginia. The Black Diamond lay at anchor about a mile south of St. Clement’s Island.

It was a clear night but there was no moon. The Black Diamond was said to have had only had one light showing. Somehow, it wasn’t seen in the darkness. At around 10 o’clock p.m. on April 23, the Massachusetts and its 400 passengers collided with the Black Diamond and her twenty crew.

What follows is a newspaper account of the incident recalled by Corporal George Hollands in 1914. Hollands was one of the soldiers aboard the Massachusetts who had spent time at Andersonville prison. His account provides a vivid description of the tragedy:

“…About 10 o’clock at night, when we were all cuddled down for a night’s sleep, part on the upper deck and part below — myself and my bunkmates were stretched out on the lower deck — we heard an awful crash and felt a sudden jar. We all sprang to our feet, pulled on our coats and ran up on deck to see what the trouble was. All was confusion and excitement, as we discovered we had crashed into the side of another boat, striking her amidship.

I ran to the bow of our boat, as most of the others had done, and found her bow was settling fast. The Captain was shouting to us to go aft, so as to keep her bow out of the water as much as possible. In the meantime we were shouting to the boat we had run into — the Black Diamond — to come to our assistance. She circled around and came up alongside of us, and about 150 jumped from the Massachusetts to the deck of the Black Diamond. I was among the first to board her, and I ran immediately to the man at the wheel and asked him if the boat was all right. He said: “No; she is sinking.” I then made up my mind that we had “jumped out of the frying-pan into the fire.” I immediately turned to go toward the stern of the boat, and in going I stumbled onto a stepladder which had been torn from the hurricane deck. I grabbed up the ladder and was about to jump overboard with it — scores of the boys had already jumped overboard to avoid the suction of the boat as she went down — when all of a sudden the thought came to me that the river was not deep enough to engulf the masts and all, so I threw down the ladder, grabbed one of the guyropes and began climbing up toward the mast.

I soon landed my foot on the yard-arm and got my arms around the mast, and about that time the boat struck bottom, with her deck only about two feet under water. I found three or four of the crew among the rigging, so they evidently were of the same mind as I concerning the depth of the river.

We clung to our positions all night, and could hear the cries for help in all directions from the boys who had jumped overboard.

A drummer boy of the 16th Conn. had been washed overboard and had grasped hold of the keel of the boat, or something else, and was hanging on for dear life and calling for help. One of the crew up in the rigging got hold of a rope and time and time again threw it to where the boy was, telling him to grab for it. The boy couldn’t get hold of it. Every now and then a wave would wash over him and strangle him, and as he would emerge from it he would call for the rope. He finally became exhausted and cried out to us that he could hold out no longer. He told us his name, but I have forgotten it. [George W. Carter] He said he was a drummer of Co. D, 16th Conn., and asked us to inform his mother that he was drowned. He bade us goodby, and as the next wave washed over him he loosened his hold and sank beneath the waves.

We clung to our position until daylight, when we were discovered and picked up by a small United States gunboat or revenue cutter and transferred to our old boat, the Massachusetts, which, with one wheel out of commission and part of her bow carried away, had floated about in the vicinity during the night and picked up those she could of our comrades who had jumped overboard.

After we were safe onboard the Massachusetts made her way slowly down the river, and about 11 o’clock a.m. she sighted a large steamer lying at anchor. She steered for her and ran alongside, and we were immediately transferred to the larger boat…”

As recalled by Hollands, in the moments after the collision many aboard the Massachusetts thought that it was their ship that was going to sink. The panicked soldiers, who had already experienced hardship and fear far beyond their years, jumped into the river with anything that would float. Many, like Hollands, sought sanctuary on the Black Diamond. However, the impact of the Massachusetts had struck the Black Diamond in the boiler and she quickly took on water. It was said the Black Diamond sank in about three minutes.

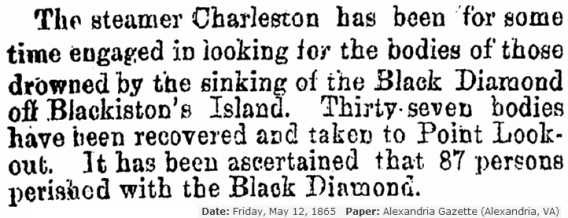

In the immediate aftermath, the death toll was estimated to be about 50 people drowned. While the newspapers of the day contained reports of the collision and the presumed number of dead, the killing of John Wilkes Booth on April 26 ensured that the focus on the crash was fleeting. Only local Alexandria and Washington, D.C. newspapers continued to report on the accident a week after it occurred. What they did report, however, showed the grim aftermath and growing number of dead that washed up on shore of St. Clement’s Island:

Out of the eighty-seven people who died when the Massachusetts crashed into the Black Diamond, only four of them were from the Black Diamond‘s twenty person crew. They were Peter Carroll, Christopher Farley, Samuel Gosnell, and George Huntington. The bodies of these four men received special treatment when they were returned to their native Alexandria:

These four men, though employed by the Quartermaster’s Department through its charter of the Black Diamond, were civilians and yet they received a high honor and were buried together in the Soldier’s Cemetery in Alexandria, now known as Alexandria National Cemetery.

These four men, though employed by the Quartermaster’s Department through its charter of the Black Diamond, were civilians and yet they received a high honor and were buried together in the Soldier’s Cemetery in Alexandria, now known as Alexandria National Cemetery.

One source states that President Andrew Johnson gave authorization for these civilians to be buried in the Soldier’s Cemetery, although substantiating evidence has yet to be found by this author. In November of 1865, some of the fallen men’s comrades erected a monument to their memory in the cemetery.

Over the years, this first monument to the lost crew of the Black Diamond deteriorated. On July 7, 1922, a new granite monument with a bronze plaque was unveiled to honor the men:

In the 1950’s the headstones for each of the four men were also quite deteriorated. They were replaced around 1955 with the new ones being of the same design as those used for Union soldiers:

The other victims of the Massachusetts – Black Diamond collision are buried all over the country but many of the bodies of those who drowned were never recovered. For example, the body of George Carter, the regimental drummer who drowned after several attempts to throw him a rope, was never found. He has a memorial cenotaph in West Suffield Cemetery in Suffield, Connecticut. It states that he “died April 24, 1865, age 20 yrs.” and that he, “Drowned near the mouth of the Potomac River”.

Today, seasonal visitors can take a quick ferry ride to St. Clement’s Island from its museum at Colton’s Point. The island is home to a recreated Blackistone Lighthouse (the original was destroyed by fire in 1956). It also boasts a 40 foot tall commemorative cross which was dedicated on Maryland Day in 1934.

Many people come to the island to tour the lighthouse, go birdwatching, hike, or just relax on the beach. Like most beaches, the sands of St. Clement’s Island are spotted with pieces of beach glass – fragments of broken glass containers that have been weathered by the wind and the waves. During my visit yesterday, I filled my pocket with pieces of the smooth glass. After taking the ferry back to the mainland, I drove straight to Alexandria, Virginia to see the graves of four men who lost their lives near the shore I had visited. On each grave I placed a small piece of my St. Clement’s Island beach glass as a reunion of sorts between the men and the place where they lost their lives.

If you visit St. Clement’s Island, you will not find any mention of the collision between the Massachusetts and the Black Diamond. The story is not told on any of the historical markers on the island nor is it mentioned (or seemingly known) in its museum on the mainland. It truly is a forgotten tragedy and its victims are more blood upon the hands of John Wilkes Booth. Had he not assassinated President Lincoln, there would have been no need for the Black Diamond to perform picket duty off of St. Clement’s. The men on the Massachusetts, who had already experienced the worst of war, would have steamed into Norfolk without incident. The shot in Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865, killed far more than the President; it also created a ripple effect that caused eighty-seven men to lose their lives.

If you’re ever at St. Clement’s Island, take the spiral staircase up the recreated Blackistone Lighthouse. At the top of the stairs ascend the ladder into the cupola. Take your pictures and enjoy the view for a bit. Then, turn your eyes to the water in the south. It was there on the night of April 23 and early morning of April 24 that eighty seven men lost their lives, collateral damage of John Wilkes Booth.

References:

A History of St. Clement’s Island by Edwin W. Beitzell

Slipped into Oblivion: A Connecticut Tragedy on the Potomac by John Banks

George Hollands’ account “On the Massachusetts“, National Tribune, 5-14-1914

American Canals, No. 48 – February, 1984, Page 9

Alexandria National Cemetery

St. Clement’s Island Museum

Newspaper articles from GenealogyBank.com

Well done and beautifully written! An important “P.S.” to the Booth esc. rte. story that few know about..

Thank you so much, Richard. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

I second Richard. Great job, Dave!

Thank you, Roger. I know you’ve had to answer emails about the monument at Alexandria National Cemetery before.

I agree wholeheartedly. This was a tragedy which is a vital part (and little known) of the Lincoln Assassination – thanks, Dave! Great story and great research!

Betty,

While I was researching this, I came across a book on the history of a certain Civil War regiment from the 1890’s. Three members of the regiment died in the Black Diamond – Massachusetts collision. A footnote on one of the pages stated: “Nothing in the preparation of this book has occasioned more searching than this Black Diamond incident.” The author was telling the truth! Thew incident so really hardly known at all. I was teaching the employees at the St. Clement’s Island Museum all about it.

Great Post! This like what happened to the Sultana.

Thanks, Herb. The Sultana was another naval tragedy that got swept under the rug quickly due to John Wilkes Booth.

Dave:

A wonderful piece. Nice work from the gadabout who does nothing by halves and takes his history in the field, thank you very much, more than from books. I knew of the incident (it’s in the book) and had the same thought you did when I read of it: that none of the 87 would have died then but for Booth. The Sultana disaster, however, was not related to the assassination, except to the extent that it too may have been the result of Secret Service operatives (coal or log bomb) rather than a defective boiler.

John

Thanks John.More info on the Sultana never hurts.I always thought that was the case.My mentor,[Albert Castel] alerted me to that incident.

Herb:

Thanks for the feedback. See Tidwell, April ’65, p. 52; G. E. and Deb Rule, The Sultana: A Case for Sabotage, North & South, Vol. 5, Issue 1, Dec. 2001; and Jerry O. Porter, The Sultana Tragedy, p. 154. All suggest a probability of a coal bomb. Fatalities are estimated at 1,200 to 1,800, which probably puts it above the Titanic (1,532) as the world’s worst maritime disaster. Desperate men do desperate things.

John

Thanks for the history lesson for this is something I never knew anything about . I have lived in St . Mary’s County since 1966 and visited the Island many times. Such a beautiful place . I would have to believe there is more history that many do not know about. Wonderful job in reporting this .

My family has lived on the shore of the Potomac, about a mile from St. Clement’s Island, for more than 40 years and we never heard this story before. Thank you for bringing it to our attention. Your article is well written and flows nicely.

I enjoyed the story, as I always enjoy the history from don cropp who I believe is the one who has restored the lighthouse and many other older properties in the area. He is a great history buff here in st. Marys, don’t know if you’ve ever spoken with him but may have some interesting stories.

Great research and article, Dave. This makes me want to visit St. Clement Island again to see it in a different perspective. It is rich in history, including this forgotten part of its history.

It was a pleasure to meet you this weekend at Rich Hill. Hope to have the opportunity to see more of your interpretive work, as well as read more of your articles.

Just happened upon your article and enjoyed it thoroughly. I am distant descendant of the Blackistone family and have heard many different stories about “the family island” over the years, but this was a new one for me. It’s my understanding that the original lighthouse was destroyed because it used for target practice by the military around 1920 or so, but I could be wrong.

This was great…. so glad this history is being shared.

Pingback: Julia Wilbur and the Saga of the Lincoln Assassination Conspirators | BoothieBarn

Saw this article on facebook, thoroughly enjoyed reading it, wasn’t aware of many of the facts.

My husband and I enjoyed reading this article.

This was a great read, an interesting bit of history that lies hidden in the pages. Thank you for writing it.

Here’s the names of three men from Company K, 9th New York Heavy Artillery (captured at Monocacy, MD on July 9, 1864, imprisoned at Danville, VA and returning to their regiment from hospital in Alexandria that fateful night: Annis Byron, Jerome Gardner, and William Harrington. Please see my study of the 9th’s casualties at Monocacy at the NY State Military Museum/s website. Thanks for the great writing and research. Ed Worman

Ed, could you email me at my home email, KarenCampbellGenealogy@outlook.com regarding Horace Fabyan? Thank you, Karen Campbell, descendant

This was a wonderful piece of writing and research! It was fascinating.

Karen Campbell

Pingback: No, you can’t go back to Blackistone Island | Kayaking in Southern Maryland

Thank you for this interesting article. I have lived in view of St. Clements/ Blackistone’s Island for more than 30 years and have never heard anything about this tragedy…

You should speak to someone in the Westmoreland News office or in the County Museum so it can be researched further and published!!

More history of this place where we live!

Due to it’s timing, it sort of reminds one of the nearly contemporaneous explosion and sinking of the steamboat Sultana on the Mississippi near Natchez, Tenn. That too managed not to make immediate headlines, despite a death toll of about 1500 to 1700 returning prisoners from Andersonville and other Confederate prisons to the North, because of Booth’s demise and the surrender of Joe Johnston’s army on April 26th, 1865.

We hope you and all of your followers will join us on April 15, 2018, on St. Clement’s Island (water taxi service provided) for the 1st annual commemoration of this tragedy on the Potomac. 2020 will mark the 155th anniversary, and we hope to be able to lay a monument at that time. We will work our way up to that with the ceremony this year, a weekend of events in 2019, and a full symposium of events in 2020. The event is free and open to the public so come one and come all! Special guest speaker is Donald Shomette. For information follow the St. Clement’s Island Museum Division on Facebook and check out our website (soon to be much improved!) http://www.co.saint-marys.md.us/recreate/Museums/. Or you can call me: Karen Stone, St. Mary’s County Museum Division Manager, at 301-769-3235.

The longer I live here, the more interesting pieces of Marylands history surfaces. I love it.

As the Museum Division Manager for St. Mary’s County I appreciate your comment. Consider joining us at the St. Clement’s Island Museum on April 27 & 28 when we commemorate the sinking of the Black Diamond and honor the memories of the 87 men who lost their lives. This is an annual event so if you can’t make it this year there is always next year…

I have only seen one account of this sea tragedy in any book on the Assassination – James Swanson described it in his account of Booth’s temporary escape and capture, “Manhunt” . Yes, it is very truly 80 more lives that were ruined or destroyed due to Booth’s conspiracy and murder of Lincoln, to be added to Major Rathbone and Miss Harris, Mary Lincoln, the eight co-conspirators (even if some, like Powell, agreed that Booth was right), Mrs. William Seward, her two sons, and Fanny Seward, and the military guard with the Secretary of State, and distant figures like the luckless Willie Jett many years later. Booth probably never considered the results of collateral damage on all these people. Nor gave a damn about it (most were Northerners).

Interesting about how the lost soldiers contained a number of survivors from Andersonville Prison. On April 27, 1865 the steamboat “Sultana” blew up on the Mississippi River above Memphis, with an overloaded passenger list mostly of former prisoners from Andersonville Prison headed North for home. Some 1,700 or so were burned or scalded to death, or drowned, making the loss of life on the Sultana the worst in U.S. history in a ship disaster, and making it over 200 more people lost than on the RMS Titanic.

Jeff

Beautifully written. I work at Friendship Firehouse Museum in Alexandria, VA and am actually familiar with this event, although, I can attest, most people are not! Telling people about a city being occupied for four years and soldiers being bored from not seeing action gives the visitor a different perspective. And then when they realize the soldiers built their own Fire Engine House, but weren’t firemen is really eye opening. It makes me wonder if that’s why they were in charge of running the Black Diamond?

In my recent I have reached a similar conclusion and would love to discuss this with you. The pandemic hit as I was getting to the point of contacting you so have not yet done that. I run the St. Mary’s County Museum Division which includes the Colton’s Point property and am in charge of the annual commemoration of this tragedy. I have been able to identify almost half of the men who died and have been in touch with some descendants which has been very inspiring. My article in America’s civil War magazine is the ing into a book project now. And this past November we were able to install a Civil War Trails marker at the Museum which tells about this incident. We are open again and back at work so I would love to talk with you more about this…