Located on the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 6th Street in northwest D.C., the Newseum is an impressive institution devoted to the evolution of news reporting and the importance of free press in a society. The seven floor museum contains impressive permanent exhibits relating to some of the most news worthy events in American and world history. There are also many galleries in the museum which house an array of different temporary exhibits. When I visited Washington, D.C. for the first time in 2009, I made sure to tour the Newseum due to the fact that they were displaying a temporary exhibition based around James Swanson’s book, Manhunt. One of my very first posts on this site recounted that wonderful exhibit.

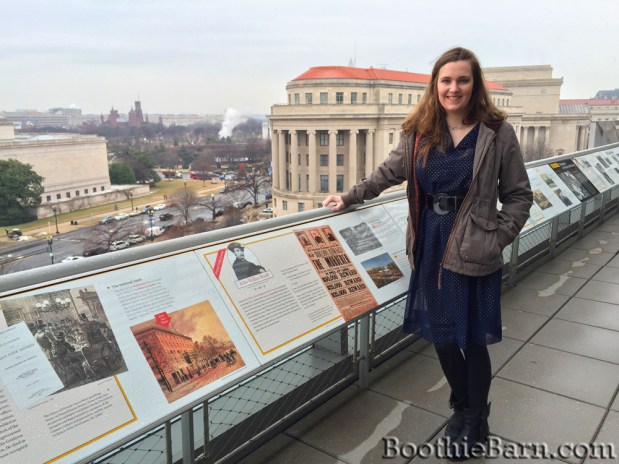

Since that time (and my subsequent move to Maryland), I have made many visits to the Newseum. Their exhibits are fascinating and it is a wonderful place to bring guests from out of town. As you might expect, there are several permanent items on display at the Newseum related to Lincoln’s assassination that I see each time I am there. One permanent, 80 foot long display on the top terrace overlooks Pennsylvania Avenue and recounts the history of Washington’s most famous street.

The display also points out that the site currently occupied by the Newseum was once the home to the National Hotel, the preferred hotel of John Wilkes Booth when he was in Washington.

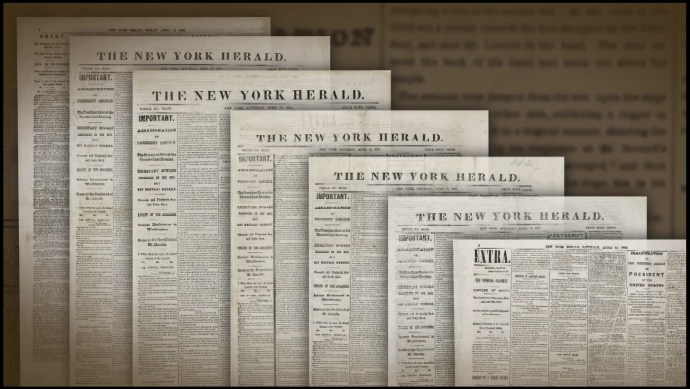

The Newseum collection also contains different newspapers, both physical and digital, that cover the assassination of Abraham Lincoln:

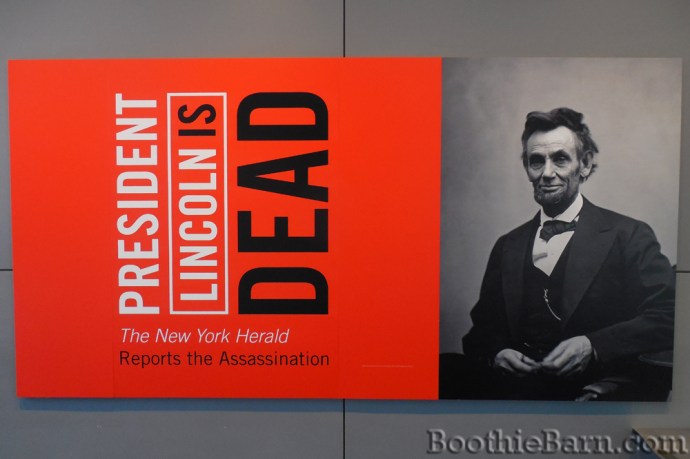

However for this year, the 150th anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the Newseum has created a very special exhibition:

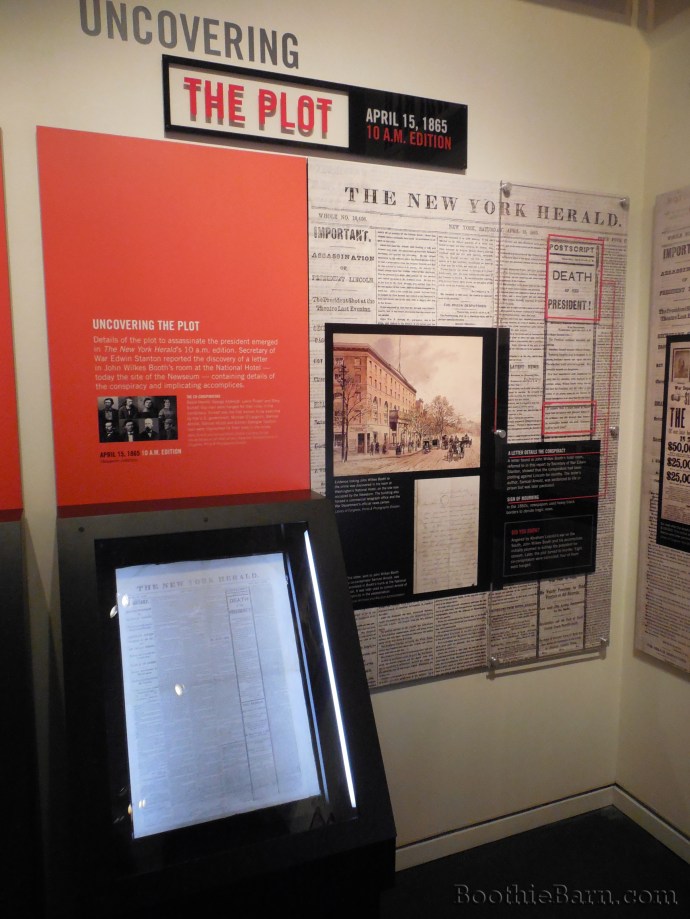

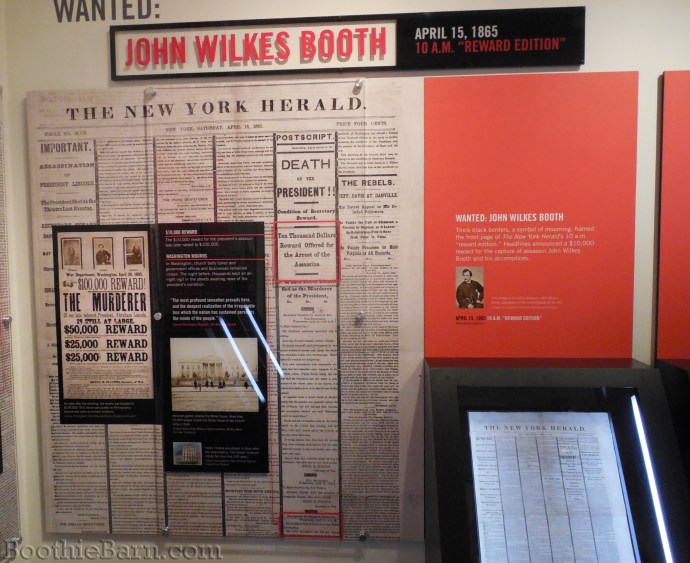

“President Lincoln Is Dead: The New York Herald Reports the Assassination” is a detailed look at how one of the most widely read newspapers in the country covered the events of April 14, 1865. Over a period of 18 hours following the shot at Ford’s Theatre, the New York Herald would publish an unprecedented seven special editions, each with new information regarding the President and Secretary of State’s conditions and the subsequent search for their assassins. The Newseum may very well be the only institution in the world that contains copies of each of the seven editions of the New York Herald from that tumultuous time.

Coverage Chronologically

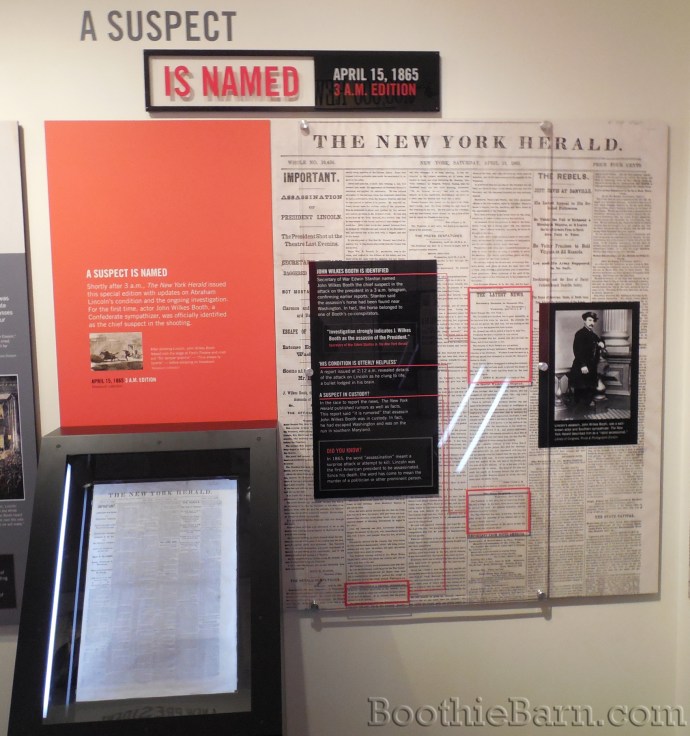

The current exhibit at the Newseum contains an original of each of these editions paired with large wall displays that highlight the differences and additions between them.

2:00 AM edition:

3:00 AM edition:

8:45 AM edition:

10:00 AM edition:

10:00 AM “Reward” edition:

2:00 PM edition:

3:30 PM edition:

Floor to Ceiling Coverage

While the “President Lincoln Is Dead: The New York Herald Reports the Assassination” exhibit is only contained in one small room of the Newseum, there is no wasted space. Even the floor and ceiling contain displays. On the floor is a map of Civil War Washington with labelled sites relating to the assassination:

Meanwhile the ceiling is festooned with wonderful banners (several of which I wish I could own myself) relating to the assassination:

The Stories Behind the Story

The displays not only provide commentary on the evolving story of how the country came to learn the details of Lincoln’s assassination, but they also introduce us to the people involved in reporting the news. One of my favorite stories is that of Associated Press reporter, Lawrence Gobright who was responsible for the very first telegraphic dispatch covering Lincoln’s assassination:

In 1869, Gobright would recollect his actions that night:

“On the night of the 14th of April, I was sitting in my office alone, everything quiet : and having filed, as I thought, my last despatch, I picked up an afternoon paper, to see what especial news it contained. While looking over its columns, a hasty step was heard at the entrance of the door, and a gentleman addressed me, in a hurried and excited manner, informing me that the President had been assassinated, and telling me to come with him! I at first could scarcely believe the intelligence. But I obeyed the summons. He had been to the theatre with a lady, and directly after the tragedy at that place, had brought out the lady, placed her at his side in his carriage, and driven directly to me. I then first went to the telegraph office, sent a short ” special,” and promised soon to give the particulars. Taking a seat in the hack, we drove back to the theatre and alighted; the gentleman giving directions to the driver to convey the lady to her home.

The gentleman and myself procured an entrance to the theatre, where we found everybody in great excitement. The wounded President had been removed to the house of Mr. Peterson [sic], who lived nearly opposite to the theatre. When we reached the box, we saw the chair in which the President sat at the time of the assassination; and, although the gas had for the greater part been turned off, we discovered blood upon it…

My friend having been present during the performance, and being a valuable source of news, I held him firmly by the arm, for fear that I might lose him in the crowd. After gathering all the points we could, we came out of the theatre, when we heard that Secretary Seward had also been assassinated. I recollect replying that this rumor probably was an echo from the theatre; but wishing to be satisfied as to its truth or falsity, I called a hack, and my companion and myself drove to the Secretary’s residence. We found a guard at the door, but had little trouble in entering the house. Some of the neighbors were there, but they were so much excited that they could not tell an intelligent story, and the colored boy, by whom Paine was met when he insisted on going up to the Secretary’s room, was scarcely able to talk. We did all we could to get at the truth of the story, and when we left the premises, had confused ideas of the events of the night. Next we went to the President’s house. A military guard was at the door. It was then, for the first time, we learned that the President had not been brought home. Vague rumors were in circulation that attempts had been made on the lives of Vice-President Johnson and others, but they could not be traced to a reliable source. We returned to Mr. Peterson’s house, but were not permitted to make our way through the military guard to inquire into the condition of the President. Nor at that time was it certainly known who was the assassin of President Lincoln. Some few persons said he resembled Booth, while others appeared to be confident as to the identity.

Returning to the office, I commenced writing a full account of that night’s dread occurrences. While thus engaged, several gentlemen who had been at the theatre came in, and, by questioning them, I obtained additional particulars. Among my visitors was Speaker Colfax, and as he was going to see Mr. Lincoln, I asked him to give me a paragraph on that interesting branch of the subject. At a subsequent hour, he did so. Meanwhile I carefully wrote my despatch, though with trembling and nervous fingers, and, under all the exciting circumstances, I was afterward surprised that I had succeeded in approximating so closely to all the facts in those dark transactions…”

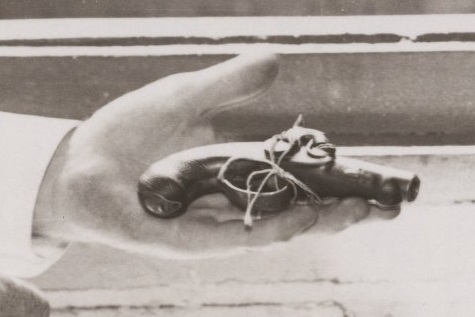

In addition to his quick reporting and continual dispatches throughout the night, Gobright also holds a place in history due to his brief custodianship over the derringer that was used to kill Abraham Lincoln.

After shooting Lincoln with the single shot pistol, John Wilkes Booth immediately dropped the gun onto the floor of the theater box. Somehow it went unnoticed during the chaos that ensued in the small box as physicians entered to care for the mortally wounded president. One of the men who had entered the box along with the physicians was a man named William Kent. Kent would later claim it was his penknife that was used to cut the collar from around Lincoln’s neck. After departing the theater that night, Kent discovered he had lost his keys and so returned to the theater and gained entry into the now empty box. He was searching for his keys when his foot struck something. Lawrence Gobright had also just arrived in the box to report on the scene of the crime:

“A man [Kent] standing by picked up Booth’s pistol from the floor, when I exclaimed to the crowd below that the weapon had been found and placed in my possession. An officer of the navy — whose name I do not now remember — demanded that I should give it to him ; but this I refused to do, preferring to make Major Richards, the head of the police, the custodian of the weapon, which I did soon after my announcement.”

As stated, Gobright did turn the derringer over to the Metropolitan Police and William Kent identified it on April 15th:

Don’t Believe Everything you Read in the Newspapers

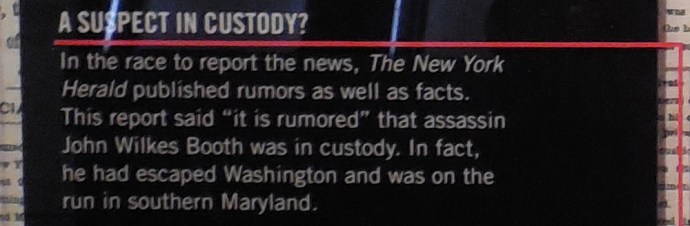

The New York Herald exhibit at the Newseum also demonstrates how the newspapers covering Lincoln’s assassination made the same mistake as some modern journalists by printing unreliable or unsubstantiated claims in hopes of being the first to provide their audience with an exclusive.

Rumors and speculation would fill every mouth, diary, and newspaper for the next twelve days as the entire country searched for John Wilkes Booth.

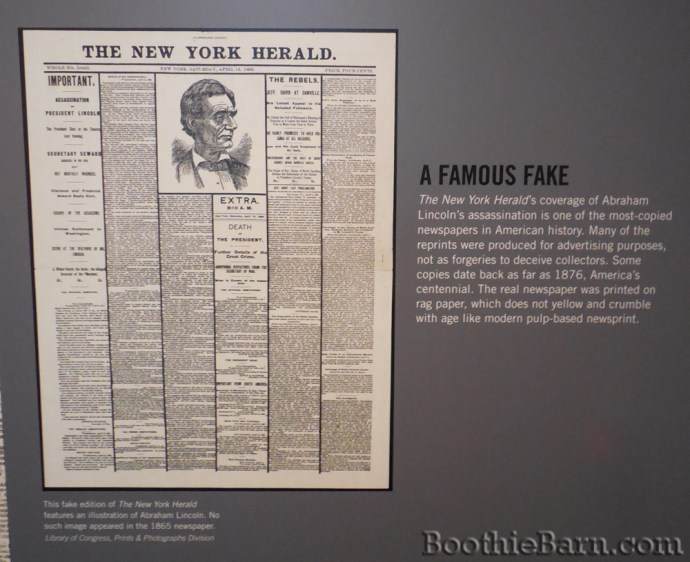

In addition to misinformation that was printed in a rush, the New York Herald exhibit at the Newseum also brings attention to later instances that have caused unintended deception. The New York Herald’s coverage of Lincoln’s assassination was so wide spread that even many years later, the paper was still very well connected to the event in the minds of the public. Many advertisers attempted to benefit from this connection by creating their own, custom reprints of editions of the New York Herald. On the face of it, the reprints appeared genuine though some, like the one below, included engravings that were never in the originals. No matter how real they looked however, hidden either in the text of the front page or within the interior pages were advertisements for the latest miracle tonic, liniment, or some other product.

This type of “historical advertising” was very popular in the late 19th and early 20th century. People were more likely to hold on to the advertisement if it had something compelling on it. Another example of this type of advertising is this reproduction CDV of John Wilkes Booth’s escape on a bag for dysentery syrup:

While the newspapers were well known to be advertisements in their day, as time has passed reproductions like the one above have fooled many unknowing treasure seekers into thinking they have a genuine (and pricey) piece of American history. Most of the time, however, a careful read through (especially of the interior pages which are usually just full page ads for the product) will reveal it is a reproduction. You can see a small sampling of some of the many advertising reproductions of the assassination editions of the New York Herald here.

Plan Your Visit

I highly recommend a visit to the “President Lincoln Is Dead: The New York Herald Reports the Assassination” exhibit at the Newseum. It is located on the 4th floor of the museum which is open daily from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm. Tickets to the Newseum cost $23 for adults and allow you to return the next day for free. While this price may seem a bit expensive compared to the federally funded museums in D.C. that offer free admission, the Newseum has many wonderful galleries and exhibits that make the price more than worth it. This special New York Herald exhibit only runs until January 10, 2016 so be sure to visit the Newseum before it is gone.

References:

President Lincoln Is Dead: The New York Herald Reports the Assassination at the Newseum

National Archives

Library of Congress

Recent Comments