When the unconscious form of Abraham Lincoln was brought out of Ford’s Theatre onto Tenth St., the men carrying the President were unsure of their destination. The street was chaotic and getting crowded with countless individuals having been drawn to Ford’s doors after hearing the dreadful news being shouted through the streets. Many would later claim to have been one of the men who transported the Great Emancipator’s frame out of Ford’s and onto the street. So many in fact, that he only way all of the accounts could be true is if Abraham Lincoln was “crowd surfed” away from the theatre. The commotion of the citizens and soldiers on Tenth street startled a young boarder across the way named Henry Safford. Having spent the previous night doing his part, “with the rest of the multitude in the celebration of Lee’s surrender,” Safford was preparing for a restful evening in his rented room on the second floor of the Petersen house. He threw open the window and called to the crowd of former Ford’s audience members, inquiring about what had occurred. Their reply of, “The President’s been shot,” startled the 25 year-old man. Safford was soon down at the door of the house, watching the crowd and keeping a close eye on Ford’s entrance for signs of a wounded, or dead, President. When the soldiers carrying Lincoln finally emerged, Safford, noticing their lack of a set destination called out, “Bring him in here!” Lincoln’s body was transferred inside of the Petersen house, and Safford led the troops into a back bedroom on the first floor. Though Safford would have been more than happy to surrender his own bed and room for the President, climbing another set of stairs to the second floor would have been too inconvenient. Safford, and other boarders in the Petersen house, would spend the night assisting the doctors by providing hot water and mustard plasters.

Henry Safford

Abraham Lincoln died in the Petersen House at around 7:22 am on Saturday, April 15th. With his death, a martyr and a shrine were born. On Sunday morning, 24 hours after Lincoln’s death, an artist by the name of Albert Berghaus arrived in Washington. Berghaus was an illustrator for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and specialized in created sketches of historical events from eyewitnesses. These sketches would be transformed into woodcuts and then published. Berghaus created this sketch of the events at Ford’s Theatre:

Albert Berghaus’ sketch of the events at Ford’s Theatre

In addition, Berghaus visited the Petersen House in hopes of sketching the room and scene of Lincoln’s demise. He employed the help of Petersen’s boarders to describe the individuals who were present in Lincoln’s final moments. His final sketch which was published in the April 29th issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was this:

“The Dying Moments of President Lincoln” by Albert Berghaus

The drawing was combined with the following affidavit:

“We the undersigned inmates of 453 Tenth street, Washington, D.C., the house in which President Lincoln died and being present at his death, do hereby certify that the sketches of Mr. Albert Berghaus are correct.

Henry Ulke

Julius Ulke

W. Peterson [sic]

W. Clarke [sic]

Thomas Proctor

H. S. Saffard [sic]”

In recognition for their help in helping him create the sketch as accurately as possible, Berhaus included five out of the six above named men in his drawing:

Julius and Henry Ulke – Brothers, photographers, and natural history buffs. It was said the Ulke’s room in the Petersen house would have been unfit for the President as there were too many beetle specimens and scientific instruments cluttering up the space.

William Petersen – German tailor and owner of the house. It was written that Petersen was a great admirer of Andrew Johnson due to the fact that he had been a tailor himself who rose to such a high position in life.

Thomas Proctor – A 17 year-old clerk for the War department.

Henry Safford – 25 year-old War department clerk. According to one source, when Edwin Stanton requested a man trained in short hand to take down statements, Safford recommended a nearby neighbor Corporal James Tanner.

The only member of the Petersen household not illustrated by Berghaus was William Clark, a 23 year-old clerk in the Quartermaster’s department. This will come into play later.

Countless other artists, period and modern, would draw their own interpretations on Lincoln’s death chamber. Every drawing, including Berghaus’, would place too many people in the small room. The 17’ by 9 ½’ back bedroom of the Petersen house has been coined the “rubber room” due to its ability to expand and contain so many people all at the same time. While Berghaus’ drawing was cited by the Petersen house residents as being the most accurate – mainly due to Berghaus’ level of detail in duplicating the details in the room – Henry Safford was honest about the rubbery-ness in the drawing: “Not all of the noted men pictured were present at the time, but had been within a few hours of the death of Lincoln.”

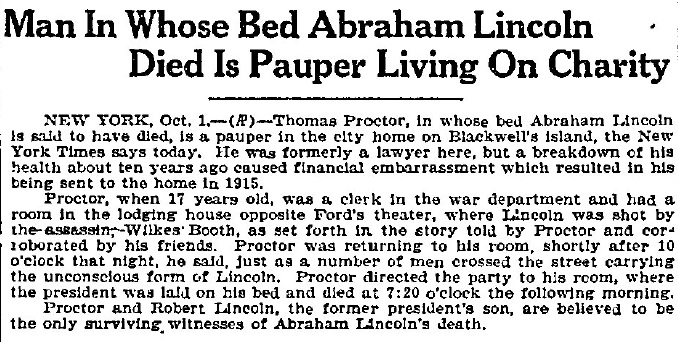

Fast-forward fifty-six years. In 1921, the only remaining Petersen house resident was Thomas Proctor.

Old Thomas Proctor

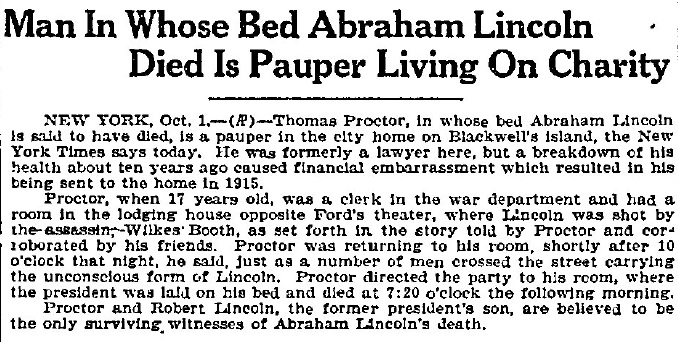

Proctor had moved from Washington, D.C. and had established himself as a prominent lawyer in New York. He married, was widowed, and in the early 1900’s began a gradual mental decline. By 1915, he had lost all of his money and had become an inmate of New York’s Blackwell’s Island, a prison and poorhouse. Still, some of his old friends and acquaintances remembered the stories he would tell of Lincoln’s last night. On Friday, September 30th, 1921, Thomas Proctor was visited by a reporter from the Associated Press. They spoke of his experiences half a century before. The next day, a news article was published across the nation:

Apparently the poor pauper Thomas Proctor was the gracious man who gave up his bed for the dying President. After reading this story, another living witness to the events of the Petersen house was intrigued. Dr. Charles Leale, the young army surgeon who first tended to the wounded President, arranged a visit with Mr. Proctor:

As this article demonstrates, Thomas Proctor’s mental state is not what it once was. Dr. Leale, though older than Thomas Proctor, must have observed the fragile mind of the man he conversed with. This visit was obviously short, and consisted of Dr. Leale leaving with little in the way of reminiscences.

This news regarding Thomas Proctor as the tenant of the bed in which Lincoln died, was the start of a controversy that stretched nationwide. At first, some papers tried to completely blow off Proctor, stating that his whole story was the invention of a troubled mind. Then, when Berghaus’ engraving came forward as evidence to Proctor’s attendance in the Petersen house, many papers declared him vindicated. Still the debate continued, with two other individuals claiming to have been the occupant of the bed in which Lincoln died. The most convincing of these claimants was the late William Clark, whose face is not included in the Berghaus engraving but whose name accompanies the affidavit attached to it. Though Clark had died in 1888, his friends wrote to the newspapers about how he was the rightful occupant of the bed and room in which Lincoln died. Suddenly, 56 yeasr after the fact, there were two legitimate groups vying for the honor of knowing the man who gave up his bed for Lincoln. The friends of Thomas Proctor used Bergahus’ engraving as evidence, while the friends of William Clark used a letter written by Clark a few days after the assassination as their evidence:

“…The same mattress is on my bed and the same coverlid covers me nightly that covered him while dying…”

The correct answer, as many reading this already know, is that the room and bed in which Lincoln died belonged to William Clark. The debate that surrounded Thomas Proctor was probably not his own doing. As we can see from his interview with Leale, Proctor needed to be led in even basic conversation. The memory of his friends were mistaken that Proctor owned the bed in which the President died and therefore led the practically senile man to that conclusion. In support of this hypothesis is an 1899 article written about Proctor in which he correctly admits that the room and bed in which Lincoln died belonged to Clark. In fact, through his own 1899 article and an 1895 article written by Henry Safford, we learn that Thomas Proctor and Henry Safford were roommates in the Petersen’s second floor apartment. Proctor was there and helped attend to the President, but the honor of the death room belonged to William Clark.

Yet the question remains, why is it that Proctor and all the other members of the Petersen house are included in Berghaus’ sketch, and yet William Clark, the tenant of the sacred room is not? Berghaus sketched all of Clark’s belongings in the room with such detail, and yet the man who lived there was not included. In Clark’s letter to his sister, the same one in which he talks about sleeping in the bed where the President expired, he relates the following:

“I was engaged nearly all of Sunday with one of Frank Leslie’s special artists, aiding him in making a correct drawing of the last moments of Mr. Lincoln. As I knew the position of every one present, he succeeded in executing a fine sketch which will appear in their paper the last of this week. He intends from the same drawing to have some fine large steel engraving executed. He also took a sketch of nearly every article in my room which will appear in their paper. He wished to mention the names of all pictures in the room, particularly the photographs of yourself, Clara and Nannie, but I told him he must not do that as they were members of my family and I did not wish them to be made public. He also urged me to give him my picture, or at least to allow him to take my sketch, but I could not see that either.”

William Clark

What is interesting here is that Clark seems to have been the only hold out in posing for the sketch. To me, this seems odd. Why wouldn’t Clark allow himself to be saved for posterity along with the others who aided the president in his final moments? For one, Clark was not in his room when the President arrived. After Clark’s passing, his family attempted to alter the record of his involvement. They told Lincoln biographer Ida Tarbell, that it was William Clark who told the soldiers to bring Lincoln to the Petersen house. This was incorrect, and Safford wrote as much to a newspaper after Tarbell’s biography was released. What’s more, Safford included a letter written to him by Thomas Proctor when the latter was in perfect health and memory:

“Mr. Clark, as you know, of course, was not at the Petersen house – on the evening, or during the night, or any part of it, of Lincoln’s death. To the best of my recollection he did not show up till the Sunday morning following. I am positive, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that Mr. Clark was not in the Petersen house at any time during the period in which Lincoln or Lincoln’s body was there, unless he was hidden away somewhere below the first floor, where it would be very difficult for even a cat to secrete itself.”

Safford agrees with Proctor’s idea that Clark was never in the house when Lincoln was there. The article ends with:

“Mr. Safford thinks that it is quite possible that Mr. Clark wrote letters home giving the impression that he was present at the time of the death. In fact, he remembers that on Clark’s return to Washington from his visit, that he (Safford) showed Clark a letter which he had written to his relatives and that Clark said he liked it and believed that he would write about the same thing to his own people. It is possible that he did this, and thus caused the misunderstanding.”

If we are to believe Henry Safford and the younger version Thomas Proctor, William Clark was not present at Lincoln’s death. He did not return to the Petersen house until the morning hours of Sunday the 16th. He arrived in time to hear the stories of what had occurred from the Ulkes, William Petersen, Safford and Proctor. When Albert Berghaus arrived to sketch the room, Clark helped in detailing the many artifacts in his room. However, when Berghaus sketched those who were present for the event, he did not sketch Clark. In his letter to his family, Clark said this was by his choice but what if Berghaus chose not to sketch Clark because he knew Clark was not there when Lincoln died? We are left with two views:

1. William Clark was the only honest man who boarded in the Petersen house with Henry Safford and Thomas Proctor spending years after his death trying to discredit him. In addition, he must also have been the most humble man in the Petersen house since he was the only one to deny having his face saved for posterity in Berghaus’ sketch.

2. William Clark embellished his involvement in Lincoln’s death to include more than, “he died in my room and bed”. He listened to the stories from those who were present and placed himself in the narrative. When Albert Berghaus arrived at the house the day after Lincoln’s death, Clark told him the truth, that he was not there, and therefore was not included in the sketch.

I leave it to the reader to decide what view they feel is most likely.

Epilogue

In the end, the debate about whose bed Lincoln died in sort of puttered out. The Sunday Herald did a wonderful job of getting to the facts and declared the old memory of Thomas Proctor to have been in error. Some other newspapers kept up their support for the pauper who gave his bed for the President, but probably just for the headline. In the end, the mistake was a blessing for the old and confused Thomas Proctor. The attention that was drawn to his story and involvement in history led to an outpouring of sympathy for his living conditions. Through the help of a Rev. Sydney Usher, Thomas Proctor was invited to relocate from the New York City poorhouse. A month after his story first ran he found a new home at the St. Andrew’s Brotherhood Home in Gibsonia, PA. According to a news article, “In his new home, the aged lawyer will be permitted to enjoy many comforts of which he has been deprived…”

Though Thomas Proctor did not rent the room or bed in which Lincoln died, he was a participant in the events that occurred in the Petersen house that night. Along with the Ulke brothers and Henry Safford, Proctor helped the doctors in providing hot water and fulfilling other requests. I have not yet been able to locate when Thomas Proctor died or where he is buried, but it can be assumed that he spent his last years enjoying charity and assistance similar to that he gave the President from those at the St. Andrew’s Brotherhood home.

Not only did Proctor’s mistaken story benefit himself, but it also was used as a seemingly effective advertising campaign for one creative insurance company:

References:

Many articles were consulted to form this post:

Henry Safford’s 1895 account

Thomas Proctor’s 1899 account

Henry Safford’s 1906 account dismissing Clark’s involvement

New York Times article supporting mistaken Thomas Proctor

Mistaken Petersen daughter stating Lincoln died in her bed

Using Safford’s material to reveal Proctor’s error

The Sunday Herald’s article conclusively proving William Clark owned the room and bed

Most images come from PictureHistory.com

Recent Comments