John Wilkes Booth’s father, Junius Brutus Booth, was a productive progenitor. With his two wives, Adelaide Delannoy and Mary Ann Holmes, Junius fathered a total of twelve children. Of these twelve children, seven survived into adulthood, five married, and four had children of their own that survived into adulthood. This post is about two of the Booth children, both of whom died young. They are Amelia Portia and Henry Byron Booth.

Amelia Portia Adelaide Booth

I discussed Amelia briefly in my last post on the Booth family, “The Son of John Wilkes Booth“. Alas I have little more to add about young Amelia because her life was short lived and there is little documentation about her. Amelia Portia Adelaide was born on October 5th, 1815. She was baptized in the Parish of St. George Bloomsbury in London on January 7th, 1816. St. George was the same church in which Junius and Adelaide were married on May 8th, 1815. In the baptism record book, which is attached below, Junius gives his occupation as a “Solicitor” instead of an actor. Amelia’s baptism took place while Junius was still making a name for himself and so perhaps the man who suddenly had a family to support was questioning his future.

Thus far, no death date or burial record for Amelia Booth has been found. However, a book published in 1817 called, “Memoirs of Junius Brutus Booth” gives the following footnote to the marriage of Junius and Adelaide: “Mr. Booth has had one child by his marriage, which died in its infancy”. This would place Amelia’s death in 1816 or early 1817.

Henry Byron Booth

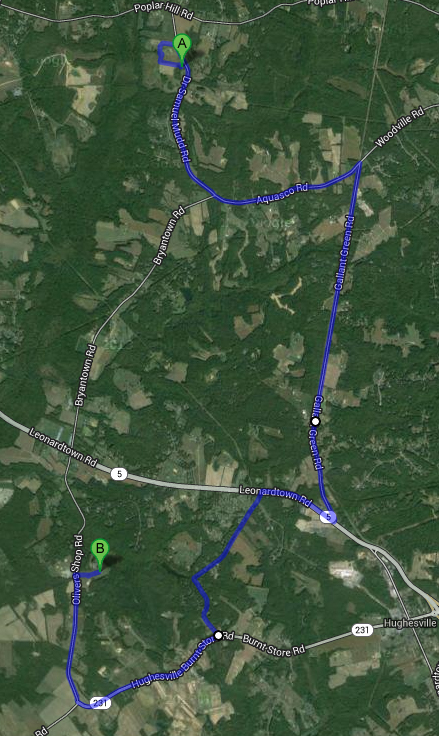

In April of 1824, Lord Byron, the renowned British poet, died at the age of 36. It was with the romantic words of Lord Byron that Junius Brutus Booth had lured the young flower girl, Mary Ann Holmes, away from her family and life in England to abscond with him to America. The poet held a special place in the hearts of the couple. It was for this reason that Junius and Mary’s third child, the first to be born after the poet’s death, received the middle name of Byron. The exact date of Henry Byron Booth’s birth is unknown. From sources, however, I have been able to deduce that he was born between April 4th and December 28th, 1825. I attempted to deduce Henry Byron’s birthdate even further by looking at the dates in which Junius Brutus Booth was home from tour with Mary Ann and the pair could have conceived Henry. Unfortunately, Junius was home from mid June, 1824 until mid March, 1825, which, 9 months later, would leave me with the same basic spread for a birthdate. If Henry Byron was born between April and about mid August, then he would have been born on the family farm near Bel Air, Maryland, the same location where seven of his brothers and sisters were born. If he was born between mid August and the end of December, 1825, however, then Henry Byron Booth’s place of birth was the same as his half siblings: England. You see about August 22nd, 1825, Junius Brutus Booth took Mary Ann, his children, and one of his servants back to London with him. This was Junius’ first return to England since he ran off with Mary Ann in 1821. The man who had formerly trumped Junius on the London stage, Edmund Kean, had recently fled to America himself after his own adulterous relationship with a married woman became public knowledge. Hoping to usurp Kean’s title yet again, Junius brought the family to England. Alas, despite the personal distaste theatergoers had for Kean and his recent adultery, Junius was still treated and reviewed as professionally inadequate to Kean’s talents. The Booth family stayed in England for about a year before returning to Baltimore on August 15, 1826. So, whether Henry Byron Booth was born in Maryland or England, he did spend the first several months of his life on foreign shores.

Junius had high hopes for this boy and he appears to have been the favorite of his father’s. While still young, Junius wrote home asking if four year old Henry could read yet, hoping to ignite the spark of creativity and genius he saw in the young boy. Ten years had passed since Junius’ last tour of England. In the fall of 1836, having witnessed his fame grow even greater in America (and the death of Kean having occurred 3 years previous), Junius decided to try his luck again in his native land. Again he was lured with offers from London managers as to the money he (and subsequently they) could earn. Across the sea he brought along the family; Mary Ann, Junius Jr., Rosalie, Henry Byron, Edwin, four-month-old Asia, and the family’s long-time servant Hagar. Junius would later write that the tour was hardly the money making endeavor promised him, “…theatricals in England are gone to sleep – with all their puffing of full houses, I don’t believe that more than two Managers in London got even enough to pay for what they individually eat.” But Junius’ time in England in 1836/1837 would be far worse than unsatisfying house numbers. On December 28th, 1836, disaster struck the Booth family while in London. The following letter, written by Junius to his father Richard back in Maryland, explains the extreme misfortune that found the Booth’s abroad:

“We have at last cause and severe enough it is, to regret coming to England. I have delayed writing till time had somewhat softened the horror of the event. Our dear little Henry is dead! He caught the small pox and it proved fatal – he has been buried about three weeks since in the chapel ground close by. Guess what his loss has been to us – So proud as I was of him above all others. The infernal disease has placed Hagar in the hospital, but she is recovering and the two youngest who were inoculated are also getting well. Junius and Rosalie have been vaccinated – so had Henry – but on him the vaccine had not taken effect and his general health being so excellent caused us to forget the danger he was liable to.”

The death of his favorite son caused a great melancholy in Junius and, “unhinged the requisite energies for coping with the Tricksters of London.” Junius made his last appearance in England on March 17th, 1837 and shortly thereafter the family returned to America. Junius would never again return to his native land and he left poor Henry buried beneath its shores.

Henry Byron Booth was buried in the burying ground of St. James of Clerkenwell near Pentonville Chapel. According to Asia Booth Clarke’s book, “The Elder and Younger Booth“, Henry’s stone bore the following epitaph:

“Oh, even in spite of death, yet still my choice,

Oft with the inward, all-beholding eye,

I think I see thee, and I hear thy voice.”

The burial took place on January 9th, 1837 as this burial record shows:

Like the London cemetery holding the body of Henry Wilkes Booth, Henry Byron Booth’s graveyard was also turned into a park around the turn of the century. As one author wrote of the burial ground in 1896, “It is nearly an acre in extent, full of tombstones and very untidy, but the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association has undertaken to convert it into a public garden.”

The cemetery in which Henry Byron Booth was buried. This image was taken just before the cemetery was transformed into a park.

Today, Henry Byron Booth’s burial place is called Joseph Grimaldi Park. Grimaldi was a famous English clown who was buried in the cemetery before its transformation. Grimaldi’s stone is the only one to have remained untouched when the cemetery was turned into a park and today it has a small gate around it. Some of the other stones that once filled the cemetery now border the walls of the park, but it is unlikely that Henry Byron Booth’s is one of them:

Junius Brutus Booth would be very distraught over the loss of Henry Byron Booth for months. It wasn’t until the birth of his next child in May of 1838, that his dark cloud would lift. In the eyes of this newborn son Junius saw again the spark of one who would change the world. This child’s name was John Wilkes Booth.

References:

London Metropolitan Archives

Junius Brutus Booth: Theatrical Prometheus by Stephen M. Archer

The Elder and Younger Booth by Asia Booth Clarke

Memoirs of Junius Brutus Booth

My Thoughts Be Bloody by Nora Titone

The London Burial Grounds by Mrs Basil Holmes

Recent Comments