On select Thursdays we are highlighting the final resting place of someone related to the Lincoln assassination story. It may be the grave of someone whose name looms large in assassination literature, like a conspirator, or the grave of one of the many minor characters who crossed paths with history. Welcome to Grave Thursday.

John B. Hubbard

Burial Location: Friendship Methodist Church Cemetery, Seneca, South Carolina

Connection to the Lincoln assassination:

John B. Hubbard’s connection to the Lincoln assassination story can be summarized in a three sentences. 1. He was one of the detectives assigned to guard the Lincoln assassination conspirators during their imprisonment and trial. 2. In this position, Hubbard was called to testify at the trial about one of his captives. 3. Two years later Hubbard was recalled to provide similar testimony at the impeachment proceedings against Andrew Johnson. While that, in essence, describes the reason John B. Hubbard first came to my attention, Hubbard’s post 1865 life makes him a worthy subject for the following lengthy post. If you have the time, please read on about John B. Hubbard, a man who not only attended the Lincoln assassination conspirators during their trial, but also raised a police force that fought against the KKK.

First off, very few details regarding the personal life of John B. Hubbard are available and it takes a bit of deducing to piece together the basic details of his life. Hubbard was likely born between 1828 and 1830. At the time of his death, newspapers claimed that Hubbard was a cousin of Horace Greeley and was originally from New York. When described during the trial of the conspirators in 1865, a reporter said he was from California. When Hubbard provided testimony during the impeachment proceedings against Andrew Johnson, he stated at the time that “My home is in Connecticut,” though it is not known if that was also his birthplace.

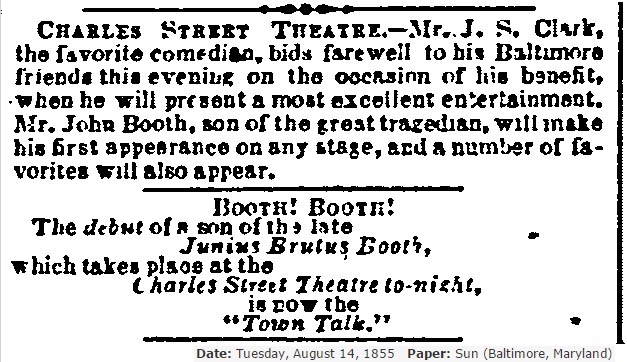

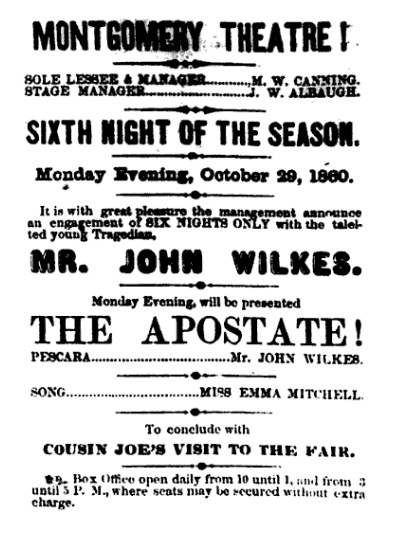

When the Civil War broke out, John Hubbard did not serve in the military. On March 25, 1865, he became a detective in Col. Lafayette Baker’s National Detective Police. At the time of Lincoln’s assassination, Hubbard was in Chicago having just come up from Springfield. Upon hearing the news of Lincoln’s death, Hubbard travelled to Washington and reported to Baker. It does not appear that Hubbard took part in the manhunt for the assassins or, if he did, his part was not effective enough for him to submit a reward request. However, once John Wilkes Booth was dead and the other conspirators were in custody, Baker did have role for Hubbard to play. Hubbard became one of four detectives who were assigned to watch over the conspirators at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary during their trial. Hubbard was joined in this assignment by fellow detectives M. Trail, John Roberts, and Charles Fellows. These four men took shifts of six hours each day to watch over the conspirators. They were entirely separate from General John Hartranft’s detachment of soldiers and staff who served as the main guards and caretakers for the imprisoned conspirators. Hubbard and the other detectives were Baker’s personal eyes and ears during the conspirators’ imprisonment, demonstrating Baker’s habit of “watching the watchers” as well.

Hubbard served as Baker’s spy at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary starting on April 29th. Once the trial of the conspirators started, Hubbard and the other detectives were tasked with further duties:

As the trial continued, Hubbard and the others became more acquainted with the men and woman they were guarding. On June 3rd, Hubbard and his fellow detective, John Roberts, were actually called to testify by Lewis Powell’s defense lawyer, William Doster. Realizing the hopeless nature of Powell’s case, Doster was trying to set up an insanity defense for his client and used words Powell had spoken to his captors to set it up. The following is Hubbard’s testimony:

John B. Hubbard,

a witness called for the accused, Lewis Payne, being duly sworn, testified as follows:By Mr. Doster:

Q. Please state to the Court whether or not you are in charge, at times, of the prisoner Payne?

A. Yes, sir: I am at times.

Q. Have you at any time had any conversation with him during his confinement?

A. I have, occasionally.

Q. Please state what the substance of that conversation was.Assistant Judge Advocate Burnett: That I object to.

The Judge Advocate: Is this conversation offered as a confession, or as evidence of insanity?

Mr. Doster: As evidence of insanity. I believe it is a settled principle of law, that all declarations are admissible under the plea of insanity.

Assistant Judge Advocate Bingham: There is no such principle of the law, that all declarations are admissible on the part of the accused for any purpose. I object to the introduction of the declarations of the prisoner made on his own motion.

The Judge Advocate: If the Court please: as a confession, of course this declaration is not at all competent; but, if it is relied upon as indicating an insane condition of mind, I think it would be better for the Court to consider it. We shall be careful, however, to exclude from its consideration these statements so far as the question of the guilt or innocence of the prisoner of the particular crime is concerned, and to admit them only so far as they may aid in solving the question of insanity raised by the counsel.

Assistant Judge Advocate Bingham: On the suggestion of the Judge Advocate General, which is entered of record, I beg leave to state to the Court that I shall not insist upon my objection.

The question being repeated to the witness, he answered as follows:

A. I was taking him out of the Courtroom, about the third or fourth day of the trial, and he said he wished they would make haste and hang him; he was tired of life. He would rather be hung than come back here in the Courtroom. That is all he ever said to me.

Q. Did he ever have any conversation with you in reference to the subject of his constipation?

A. Yes: about a week ago.

Q. What did he say?

A. He said that he had been so ever since he had been here.

Q. What had been so?

A. He had been constipated.

Q. Have you any personal knowledge as to the truth of that fact?

A. No sir, I have not.By the Judge Advocate:

Q. To whom did you first communicate this statement of his?

A. To the officer.

Q. What officers?

A. Colonel Dodd, I think, or Colonel McCall, and, I believe, to General Hartranft.

Q. Nobody else?

A. No, sir.By Assistant Judge Advocate Bingham:

Q. What else did he say in his talk the third or fourth day of his trial?

A. I have given all he said going downstairs.

The question directed at Hubbard regarding Lewis Powell’s constipation may seem irrelevant, but that subject was broached the day before by another Doster witness, Dr. Charles Nichols. Nichols assented to Doster’s claim that constipation over a long duration could be taken as evidence of insanity. Doster would use the testimony of Hubbard and his next witness, Col. McCall of General Hartranft’s staff, to prove that Powell had been constipated for almost five weeks in his attempt to strengthen his insanity defense.

Hubbard’s fellow Baker detective, John Roberts, also testified regarding Lewis Powell. Roberts stated that, on the day Powell was asked to put on the clothes he was wearing on the night of April 14th and was subsequently identified by Seward’s son in court, Powell had told him (Roberts) that the prosecution was, “tracing him pretty close, and that he wanted to die.” Doster was hoping to use Hubbard’s and Roberts’ testimony to demonstrate Powell’s suicidal thoughts and, therefore, further insanity.

In the end, of course, Doster’s insanity defense for Powell was unsuccessful. Hubbard and the other detectives were undoubtedly present on the hot afternoon of July 7, 1865 when Lewis Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt and Mary Surratt met death upon the gallows. After the deaths of half of the conspirators, half of Baker’s detectives were reassigned:

On July 17th, there was no longer any need for John B. Hubbard to remain at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary as the remaining four conspirators were placed aboard a steamer and sent to Fort Jefferson prison. Hubbard would leave Baker’s employ not long after that. For his services with Baker, Hubbard was paid $150 a month.

In 1866, John B. Hubbard made his way down to South Carolina which was then part of the Second Military District. After the close of the Civil War, the U.S. Army created several administrative units in the former Confederate states. The districts acted as the de facto military government of those states until new civilian governments were re-established. The new state governments were required to ratify the 14th amendment which granted voting rights to black men. In the Second Military District, which compromised North and South Carolina, John B. Hubbard found employment as a detective for the commander of the district, General Daniel Sickles.

On May 17, 1867, John Hubbard was called up from South Carolina to testify at the impeachment proceedings against President Andrew Johnson. His testimony in Washington was brief and mainly concerned his duties during the conspiracy trial. He was asked about any confessions that may have been written by the conspirators during his time with them. The only one he recalled was one written by George Atzerodt. Hubbard claimed he did not believe Lewis Powell ever wrote a confession. For this brief testimony, the government paid Hubbard $49 for his 3 days and 470 miles of travel. He subsequently returned to South Carolina.

In August of 1867, General Sickles was removed as commander of the Second Military District and was replaced by General Edward Canby. Hubbard continued in his services as a detective for General Canby until the district was dissolved upon South Carolina’s adoption of a new state constitution and re-admittance to the Union in 1868. The first elected Governor of South Carolina under the new 1868 Constitution was Robert Kingston Scott, a former Union brigadier general and a Republican from Pennsylvania. The new state constitution arranged for the organization of a new state police. Gov. Scott chose John Hubbard to become the state’s first Chief Constable.

During the Reconstruction Era, people like Gov. Scott and John Hubbard were referred to as carpet-baggers. This term was used to describe northerners who moved to the conquered South for their own personal gain and, ostensibly, brought their few belongings with them in cheap carpetbags. The term was not without merit as the most notorious carpetbaggers truly were unscrupulous individuals seeking only to gain power and wealth at the expense of the locals. However, not every northerner who moved to the South during Reconstruction was a carpetbagger. Nevertheless, the term came to represent all northerners who moved to the southern states during Reconstruction regardless of intent.

Denouncing and attacking all northerners as carpetbaggers became one of the main strategies of the southern papers during Reconstruction. The view that all carpetbagger officials were engaging in graft, bribery, and embezzlement was so pervasive that it is very difficult to tell the difference between true instances of carpetbaggery and anti-northerner propaganda.

However, as problematic as financial corruption on the part of carpetbaggers was, what was far more damaging to the sensibilities of white Southerners was the forced advancement of racial equality in the region. The South lost the Civil War and was forced to abandon slavery, but it could not be forced to abandon its belief in white supremacy. As Republican controlled governments established themselves in the South and pushed to ensure equal voting and citizenship rights for the recently freed slaves, the white Democratic populations pushed back with often violent vengeance. (Note: It is important to remember that while the two main political parties of today share the same names as those in existence 150 years ago, the viewpoints of each party have shifted significantly over time. The Republican and Democratic parties of today have little in common with their counterparts of the past.) It was during this time that one of the first incarnations of the Ku Klux Klan arose in South Carolina. As Chief Constable of the state, John B. Hubbard gave a deposition about the Klan’s activities and the work of his force to try to contain them:

“In all the counties except one there were threats, intimidations, and violence used against republicans. Men were taken out by the Ku Klux and whipped, to frighten them from voting the republican ticket. My subordinates officially notified me that in all the counties west of Broad River, as well as in York County, Ku Klux abounded in numbers, and spread general terror all over the county…In Laurens County cases were officially reported to me in which men were stationed on the highways to prevent republican voters from going to the polls. Numerous outrages and murders were perpetrated on republicans. There was one case in which, in the town of Laurens, a man was publicly shot down in the streets for simply saying he was a republican; another case, in which twenty shots were fired upon a republican in daylight, until he was chased entirely out of town…I daily expected to hear that my deputies were killed, and that anarchy had taken possession of the county.”

The widespread attacks against South Carolina’s Republican voters described by Hubbard above occurred during the election of 1868. The Klan’s efforts to intimidate Republican voters, both white and black, caused the black voter turnout in 1868 to be extremely low. Elaine Frantz Parsons, author of Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan during Reconstruction, noted that, “The dramatically lopsided election results in 1868 seemed clear proof to Republicans of a massive campaign of voter intimidation, but Democratic newspapers cynically shrugged it off. Nothing that in the Ninety-Sixth District only eight or ten black men voted, the Charleston News explained, ‘The colored people did not desire to vote and preferred to stay at home.’”

In order to combat the widespread voter intimidation practiced by the Ku Klux Klan, Gov. Scott gave Hubbard the funds and authority to help raise local black militias for the purposes of defense of the Republican citizens. Hubbard’s various constables throughout the state aided the militias in various ways. When Democratic supporters provided Winchester rifles to members of the Ku Klux, Hubbard, in turn, managed to get rifles for some of the militia men. Hubbard desired a larger paramilitary force of Northerners to send to counties where there had been intimidation and in 1870 Gov. Scott agreed to the idea. They commissioned C.C. Baker, a New York carpetbagger who ran a gold mining business in Union county, to go to New York and find men to work as “detectives”. Baker outsourced the job to a man named James Kerrigan who assembled twenty five men. Years later, Hubbard would admit that, “I don’t think it possible to have found or selected a more dangerous lot of men than were in any city of the union.” Parsons explains the failure of this force:

“While there is no record of the Kerrigan detectives causing problems during their stay in Union,Scott’s decision to bring them to Union only confirmed Democratic white’s fears that the Republicans would use their superior bureaucratic organization and resources to mobilize force from beyond the county… Kerrigan’s men did very little, generated no indictments, and left within a few days. But the presence of these hired detectives fed dramatically into Democratic Union Countians’ sense of lack of control… Things did not turn out as Scott and Hubbard had planned”

Bringing in this large number of carpetbaggers to intimidate the Ku-Kluxes in Union actually did the opposite. This event and a subsequent murder of a white man by one of the black militias (likely one of the only times the militias themselves were violent), caused the community of Union to unite behind the Klan. They subsequently engaged in two prison raids and mass lynchings which were covered nationwide and caught the attention of President Grant. The atrocities caused by the Klan in South Carolina helped push Enforcement Acts through Congress. These acts allowed federal troops to enforce the law in the South rather than relying on state militias. It resulted in the arrests and trials of hundreds of Klan members and the suspension of habeas corpus in nine counties in South Carolina. The Enforcement Acts virtually destroyed the Klan in South Carolina and greatly reduced its power throughout the rest of the South. It would not be until 1915, upon the release of the film, The Birth of a Nation, that the Klan would reassemble itself. The acts essentially put Hubbard’s deputies out of a job as his force was superseded by federal troops who were far more effective. While Hubbard’s force disbanded, Hubbard did not. In 1872, a year after the third Enforcement Act was put into place, Hubbard is listed as living in Charleston as a Deputy U.S. Marshal. In this capacity he aided the federal troops in making arrests and identifying Ku Kluxes and Ku Klux crimes throughout the state. For two years he worked with the federal troops to rid South Carolina of the KKK with great success.

In 1874, after two years as a Deputy Marshal, Hubbard left the law and became a Special Agent for the Treasury Department. His duties in this position and length of tenure are unknown.

This political cartoon depicts Rutherford B. Hayes strolling off with the prize of the “Solid South” having made a deal with the Devil.

Reconstruction ended with the Great Betrayal of 1877 which gave Rutherford B. Hayes the contested presidency in return for him pulling all remaining federal troops out of the South. With the troops gone, there was no way to apply the Enforcement Acts and the large scale disenfranchisement of black voters began at a state level.

This was also the period of time when the Democratic leaders sought to punish those carpetbagging Republicans who had controlled their states during the Reconstruction years. Charges were brought up against many former Republican officials. The author of Hubbard’s later obituary stated that, “When Democrats overthrew the reconstruction Government in 1876, Hubbard left the State Capitol and fled to the mountains in the northwestern part of the State where he has lived ever since… How he managed to escape their vengeance is still a mystery.” The truth is, Hubbard did not escape the vengeance of the Democrats who now held power. In order to save himself, Hubbard turned against a bigger carpetbagger than himself, his former boss, Governor Robert Scott.

Scott’s tenure as governor ended in 1872 and, though he had continued to live in South Carolina afterwards, he fled the state when the Democrats took power in 1877. Hubbard was either not so quick or had grown attached to his southern home. Rather than run, in 1878, Hubbard subjected himself to be interviewed by the Democrat’s Joint Investigating Committee on Public Frauds. He gave a long testimony and produced many records and correspondences. The committee believed that Gov. Scott had misappropriate massive amounts of funds (which he likely did) and that Hubbard’s constabulary was used for the express purpose of helping Republican candidates and to intimidate Democratic voters. Hubbard reinforced the very notions the committee was looking for but his motive for doing so are unknown. He acknowledged that his constabulary of deputies was used to promote Republican candidates and support Republican voters. Hubbard also laid the blame on Scott regarding the (failed) attempt to establish a paramilitary force of white Republicans in Union. Hubbard provided enough correspondence from his deputies to satiate the committee’s belief that his police force was merely a propaganda arm for the Republicans. To hammer the final nail into the coffin, Hubbard stated flatly that, “Ostensibly, the object of the constabulary force was for the preservation of the peace, but in reality it was organized and used for political purposes and ends.” For this testimony, even though it seemed to prove that Hubbard was engaged with Gov. Scott in the misappropriation of funds in order to intimate Democratic voters state wide, Hubbard was sincerely thanked.

Hubbard’s testimony in 1878 is perplexing. While there is obvious truth that his deputies were tasked with supporting the Republican candidates and voters, this was largely done due to the large scale voter suppression they were facing. Hubbard’s additional claim that the force was organized purely for political purposes also discounts the many arrests that the deputies, and Hubbard himself, made to maintain law and respect the rights of the black citizens. Perhaps the incongruous part of Hubbard’s testimony is his claim that, prior to the establishment of the black militias, there was “but little lawlessness” in the counties. This idea is completely contradicted by his report on the Ku Klux Klan activity which preceded the establishment of the militias. Granted the violence did increase after the establishment of the militias but what preceded it would hardly have been referred as “little lawlessness”.

In the end, the motives of Hubbard’s 1878 testimony are unknown. Did he provide the investigating committee with the information and testimony they sought, even if it was not completely accurate or his true feelings, in order to save himself? Or did Hubbard truly come to think of his former police force as nothing but a political tool that was abused by the former Governor?

Regardless of his true feelings, Hubbard’s testimony apparently allowed him to remain in South Carolina without issue. Though, it should be noted, Hubbard did move from his former homes in Columbia and Charleston to the relatively isolated region in the state’s northwest. On July 4, 1880, John Hubbard married Eliza C. Fredericks at her home in Seneca, South Carolina. Hubbard was about 50 years old and his new bride was 47. Their marriage lasted only eight years before John’s death.

John B. Hubbard died on December 17, 1888 near Seneca. When the newspapers reported his death they briefly recounted that he had, “taken a prominent part in the execution of Mrs. Surratt” and was “a chief advisor” in the breakup of the KKK. The papers had little to add about his final years. “It is said he was a moonshiner,” they reported. “For the last four or five years he had disappeared altogether from public notice. He died in his mountain vastness.”

Eliza Hubbard outlived her husband by a number of years before dying in 1900. She is buried alongside him in Friendship Methodist Church Cemetery in Seneca. Unfortunately, both of their gravestones have been broken in half.

Like many Grave Thursday offerings, John B. Hubbard is a minor character when it comes to his involvement in the story of the Lincoln assassination. Nevertheless, when making plans to visit South Carolina in order to view the recent eclipse, I made sure that I found lodging not far from his final resting place. I wanted to find the grave of this man who had such an interesting life beyond 1865. John Hubbard is still very much a mystery in some respects and his true feelings regarding his deputy force are difficult to know for certainty. Nevertheless, I believe that John Hubbard’s legacy should be that he opposed the KKK. He and his deputies fought against the Klan’s attempts to intimidate and prevent African Americans from engaging in their right to be heard and represented.

While doing research for this post, I stumbled across the KKK book quoted earlier by Elaine Frantz Parsons. The details I found regarding Hubbard convinced me to purchase the digital version. I often buy books like this solely for reference purposes, taking out the parts relating to my particular subject but never reading the entire text cover to cover. Though my initial intent was to use the book just for the parts relating to Hubbard, I have found this book extremely engrossing and have already read far beyond any mention of Hubbard. It is an emotionally difficult read but extremely relevant, I think, to current events. I was particular fascinated with how the Democratic newspapers of the time reported on the KKK atrocities. Parsons aptly notes that the, “Democratic elites kept their standard posture of publicly admiring the idea of the Ku-Klux while rigorously denying any local accounts of Ku-Kluxes or Klux attacks”. The denial of local attacks (or claims of “fake news” in modern parlance) was maintained as long as possible until enough outside reports forced the newspapers to acknowledge them. But even when the attacks were finally acknowledged, the Democratic papers in Union County printed story after story about how the crimes reported had actually been carried out by the black Republican militias who were being paid by wealthy radical Republicans in the North to stage attacks and even kill their own in order to illicit sympathy in the North. All of this propaganda worked to turn people to the same side as the KKK without them realizing it. Average citizens, many of who would never put on a hood themselves and cause violence, surrendered the basic tenants of their Christian morality when they embraced the fear and conspiracy of the propagandists. Parsons points out that though the first KKK was physically destroyed through the Enforcement Acts, its ideas were not. Through their few years of violence and support in the propagandist newspapers, they successfully turned public opinion in their favor and scared those who would stand against them into silence. They lost their form when federal troops came to oppose them, but, when Reconstruction ended, their ideas were put into place when the suppression of black voting rights continued and Jim Crow laws were enacted.

It is for this reason that I admire John Hubbard to a degree. When Hubbard fought against the KKK, he faced immense backlash from those around him. He was detested for being an outsider and the newspapers condemned him for trying to force his will on the local population. Hubbard himself mentioned the dangers he faced in travelling into KKK dominated counties, “Every time that I myself went into those counties I thought I would not get back alive. I was told by prominent democrats that I would not get back; that I would be killed…that their political friends had sworn to kill me.” Even in the fact of all this, however, Hubbard continued to fight. First with his own police force and then with the federal troops who came into the South.

John B. Hubbard may have been a carpetbagger. He may have used his constabulary for political purposes. We may never truly know his motives. But, when all is said and done, John Hubbard opposed the KKK and its propaganda, and that puts him on the right side of morality and history.

References:

Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan during Reconstruction by Elaine Frantz Parsons

The Lincoln Assassination Trial – The Court Transcripts edited by William Edwards

John Hubbard’s testimony in Impeachment Investigation: Testimony Taken Before the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives in the Investigation of the Charges Against Andrew Johnson

John Hubbard’s Ku Klux Klan report in House Documents, Volume 265

Report of the Joint Investigating Committee on Public Frauds and Election of Hon. J.J. Patterson to the United States Senate: Made to the General Assembly of South Carolina at the Regular Session 1877-78

Newspaper articles accessed via GenealogyBank.com

Recent Comments