I’m very grateful to Joe Barry and his piece “Will Research for Peanuts,” which he recently contributed to this website. Through his research, Joe put together the known facts about Peanut John and documented some of the theories that exist about the identification of this young man who innocently held John Wilkes Booth’s horse behind Ford’s Theatre.

Inspired by Joe’s work, I decided to do a little bit of digging into Peanuts on my own, and I have come up with my own possible theory. While I originally received Joe’s approval to add my speculation to the end of his piece, I didn’t want to detract from his writing with my own, lengthy conjecture. Instead, consider this post to be my own addition to the Peanut John discourse.

The main issue with trying to research this young man who held Booth’s horse is a lack of a consistent name. He was nicknamed variations of “Peanut John” and “John Peanuts” by the stagehands and employees at Ford’s Theatre. Harry Clay Ford, one of the managing operators of Ford’s Theatre, admitted to not knowing his employee’s full name, stating, “We have a doorkeeper at the back door, John. I don’t know his last name. The boys call him ‘Peanut.’ He is expected to keep the back door, and he works around the theater.” To Ford’s credit, he did not have much in the way of interactions with Peanuts, as the boy usually acted under the direction of James Gifford, the chief carpenter of the theater.

In one of his statements to the authorities, Peanuts notes that “They generally call me John Peanuts around [the theater] because I used to peddle peanuts.” It was not uncommon for individuals to sell small treats and concessions such as peanuts and candy to theater guests. In fact, Peanuts was actually one of several boys who engaged in this practice.

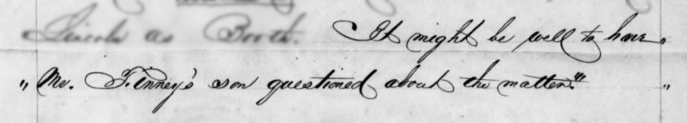

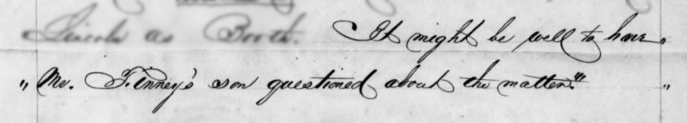

For much of the Civil War years, Dr. Ithamer S. Drake had been employed as a clerk in the Census Bureau in Washington, D.C. During the latter part of his employment, Dr. Drake resided with his family on 9th Street. Just about a week before the assassination, the Drake family had moved back to the doctor’s home in Richmond, Indiana. After hearing of the national calamity in Washington, Dr. Drake wrote a letter to an acquaintance of his who still resided in the city. The recipient was William A. Cook, a clerk in the General Land Office in the Department of the Interior. Dr. Drake noted to Cook that, “My youngest boy was in the habit of going through the theater with other boys.” The doctor then recounted how this son, Frank, informed him that during his time around Ford’s Theatre, he had heard disloyal talk from the scene painter at the theater, James Lamb, at the time of the fall of Richmond, Virginia. Dr. Drake alluded to possible conversations between Lamb and John Wilkes Booth that he felt should be investigated. In the letter, Dr. Drake informed Cook that one of the boys his son hung out with at the theater was David Finney and that he should be questioned on the matter.

With the permission of Col. John Foster, one of the special commissioners engaged in investigating the assassination, William Cook interviewed David Finney at his father’s home on the corner of 9th and H Streets. Finney, who was about 15 years old at the time, described to Cook that while he did not recall any disloyal statements from Lamb when the Confederate capital fell, he did recall Lamb chastizing some revelers on the night of the Grand Illumination to celebrate the Union’s victory on April 13th. David Finney pointed out that Frank Drake was more acquainted with the people in the theater since the doctor’s son was “allowed to sell ‘gumdrops’ etc. in the building.”

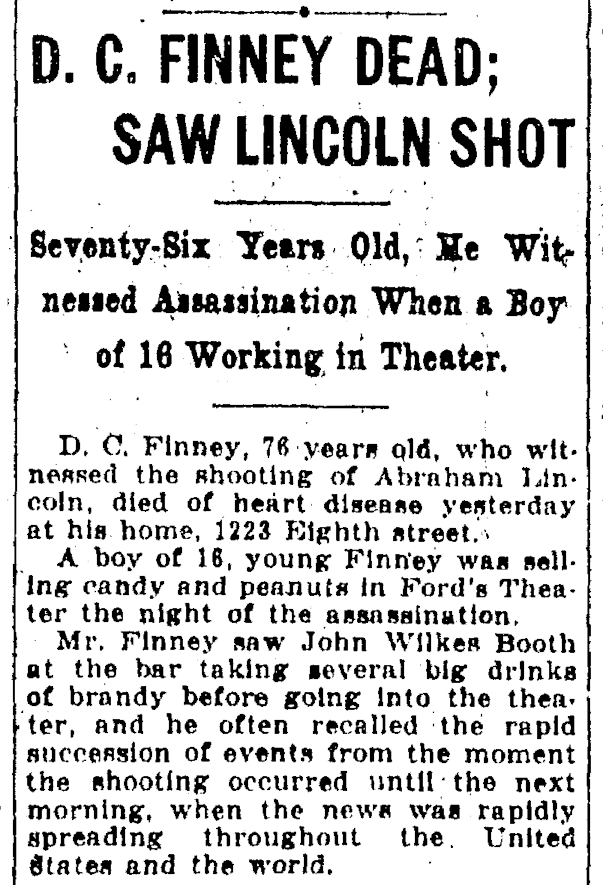

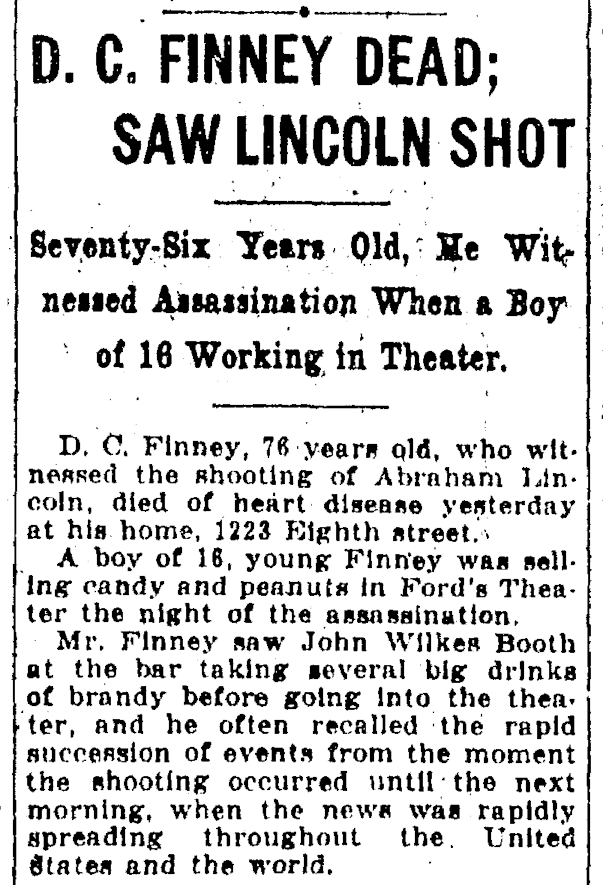

In this way, we know that Frank Drake acted as a sort of gumdrop and peanut boy at Ford’s Theatre. But he had left D.C. with his father shortly before the assassination, so we know he’s not our Peanut John. While in his statement to Cook, David Finney makes it seem like only Frank Drake was involved in the gumdrop trade, when Finney died in 1925, his obituaries noted that he also sold “candy and peanuts in Ford’s Theatre.” Moreover, these obituaries state that Finney was selling concessions the night Lincoln was killed and witnessed the events. In addition, one of Dr. Drake’s other sons, Albert, also told his father about the goings on at the theater, making it likely that there was a small cadre of boys who hung around the theater and made extra money selling gumdrops and peanuts.

While Peanut John had received his nickname from selling peanuts around the theater, he had clearly advanced beyond this role at the time of the assassination, leaving the job to boys like David Finney and the Drake brothers. As noted by Harry Clay Ford, Peanut was tasked with guarding the stage door: “He is to keep all strangers out, everybody…His instructions are not to let strangers on the stage.” In his own testimony, Peanut described his role thusly: “I used to stand at the stage-door, and then carry bills in the daytime.” During the day of April 14, Peanuts also assisted in the decorating of the Presidential box. In short, Peanut John was a gofer of sorts, fulfilling any small task given to him by James Gifford or anyone at the theater.

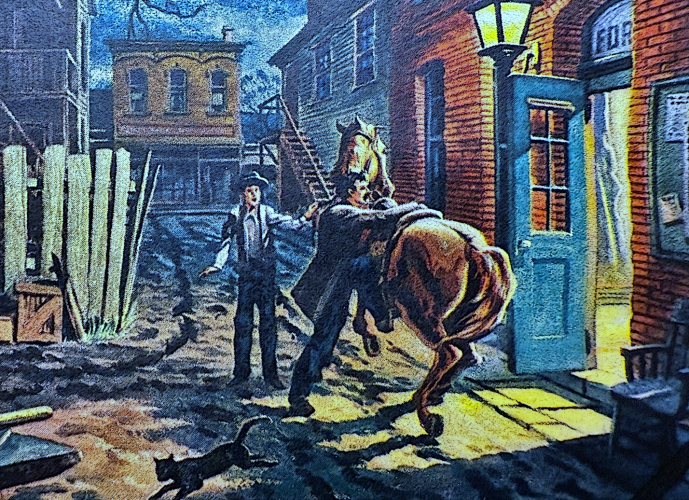

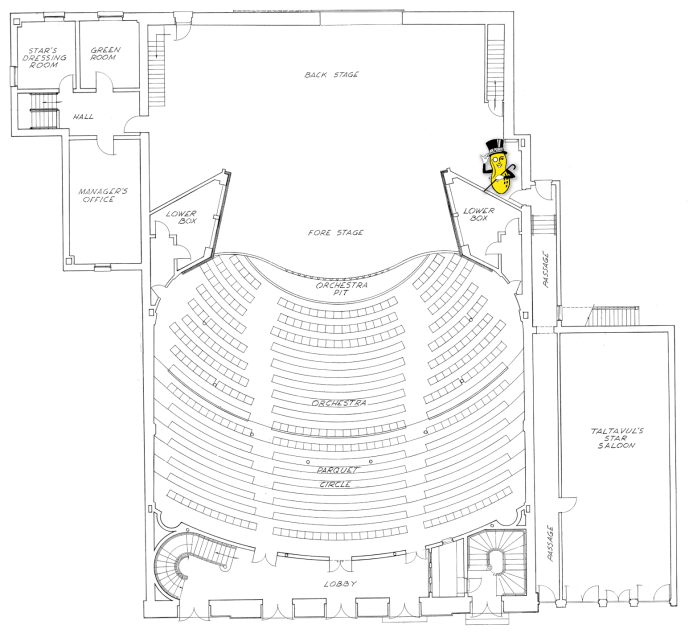

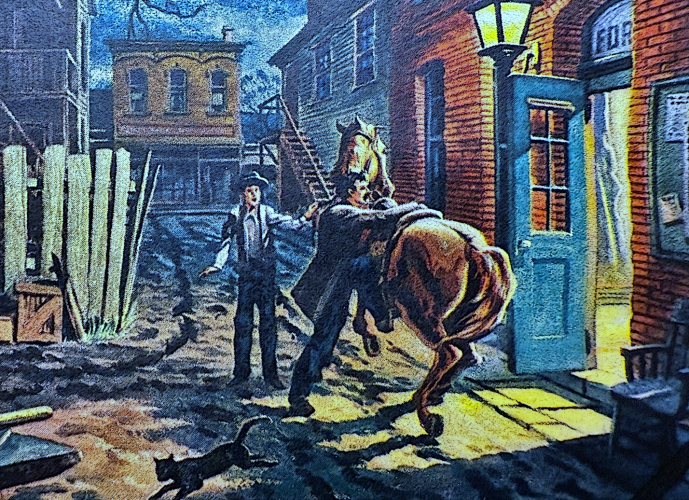

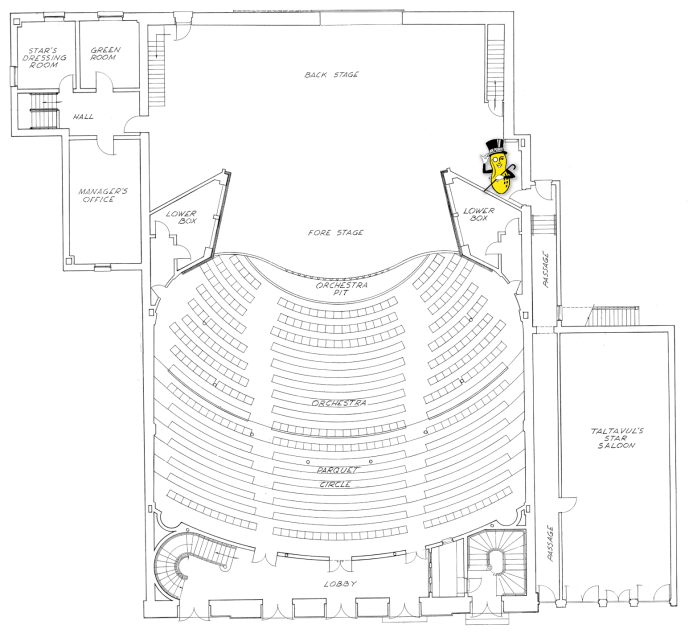

It’s worth pointing out that the stage door that Peanuts was tasked with guarding during performances is not the back door through which John Wilkes Booth entered. Rather, his place was located stage left on the south side of the building. A covered alleyway of sorts ran from Tenth Street all the way to the rear of Ford’s Theatre into Baptist Alley. This walkway separated Ford’s Theatre proper from the Star Saloon located just to the south. A side door of the Star Saloon led directly into this passageway, and it appears the Fords may have had an issue with bar patrons mistakenly opening the door directly onto the stage during performances. Therefore, Peanut John guarded this door, preventing anyone from accidentally interrupting a performance. When Peanuts was called by Edman Spangler, he abandoned his normal post to hold Booth’s horse directly behind Ford’s Theatre.

Location of Peanut John’s normal station, guarding the stage door at Ford’s Theatre

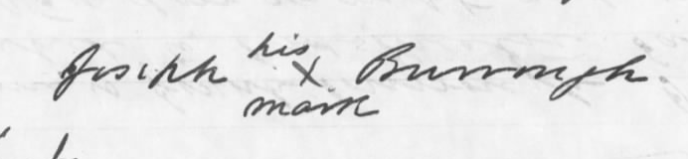

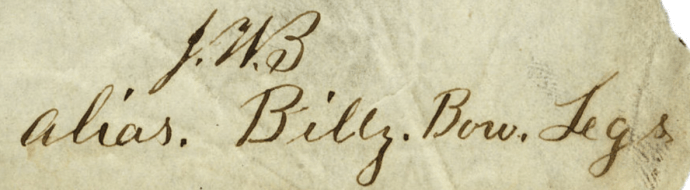

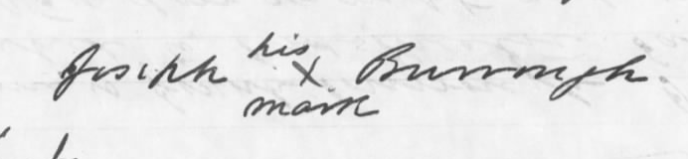

Prior to taking the stand at the trial of the conspirators, Peanut John gave two statements to the authorities. The first was on the morning of Lincoln’s death, April 15th. Edman Spangler was arrested around 6:00 am that day and taken to the police station on E Street between 9th and 10th. He had been brought in by Sergeant C. M. Skippon. As Spangler later recalled, “The sergeant, after questioning me closely, went with two policemen to search for Peanut John (the name of the boy who held Booth’s horse the night before) and made to accompany us to the headquarters of the police on Tenth street, where John and I were locked up…” After a period of time in confinement, both Spangler and Peanut were brought before Abram B. Olin, a Justice of the Supreme Court of D.C., who examined them individually and took down their accounts. Peanut John dictated two pages to Justice Olin. In this document, his name is given as Joseph Burrough. As noted by Joe in his article, he does not sign this name, however. Instead, he merely puts an “X” as his mark. Generally speaking, making an X implies that the person could not write their own name and that they may be illiterate.

Due to Peanut not signing his name, Justice Olin needed a witness to swear to the fact that Peanut had, in fact, made the X himself. For this, Olin recruited the assistance of another witness who was awaiting examination. William T. Kent had been present at Ford’s Theatre and witnessed the shooting. After the call went up for help, Kent made his way into the Presidential box to render aid. When Dr. Charles Leale required a blade of some sort to cut open Lincoln’s shirt, Kent provided his penknife. After leaving the theater, Kent realized that he had lost his keys in the confusion. He was granted access back into the theater and searched the box. During his search, Kent came across the derringer used to shoot Lincoln. It was dropped in the box and kicked into a corner during the work to save the President. Kent took the gun and turned it over to the police, and he was now waiting his turn to tell his story to Justice Olin. The Justice thus had William Kent act as a witness to Peanut’s “signature” on this statement. Then it appears that Peanut John was released.

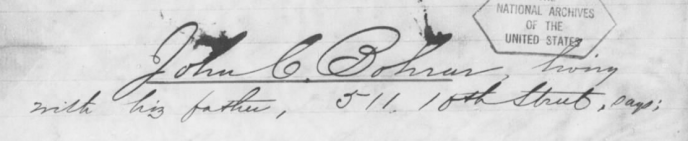

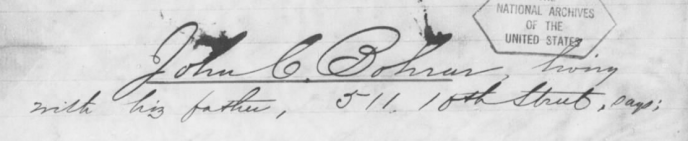

Nine days later, Peanut was interviewed again about the circumstances and people at Ford’s Theatre. This conversation on April 24th was transcribed onto six pages. The name given for this interview is John C. Bohrar, though there is no signature section at the end (X or otherwise). In this interview, Peanut gives more details about his caring for Booth’s stable behind Ford’s Theatre, and the circumstances of how he ended up holding Booth’s horse on the night of the assassination. While the name John Bohrar is different from Joseph Burrough, it’s clear that the same person was interviewed in both statements.

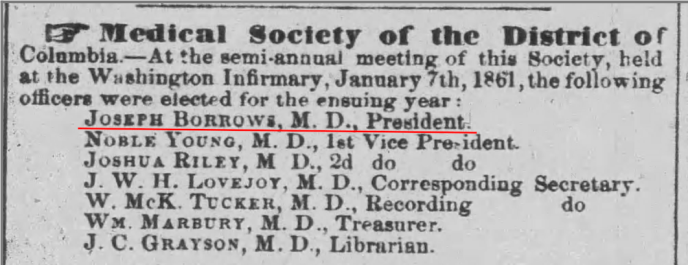

In his article, Joe explored the different Joseph Burroughs/Borrowses that have been suggested as possibly being “our” Peanut. Michael Kauffman theorized in American Brutus that Peanut might have been a son of Dr. Joseph Borrows, who lived right on E Street near Ford’s Theatre. But, thus far, we can’t seem to prove that Dr. Borrows had a surviving son at the time of the assassination. Fellow researcher Steve Williams tracked a Joseph A. Burroughs, who lived in Tenleytown (a neighborhood in the far northwest quadrant of D.C.) and later moved to Baltimore. He would have been about the right age for the teenage Peanuts, but this Burroughs is shown to be literate.

While these possibilities are interesting, I would like to suggest that they may be based on a wrong assumption. The names we’ve explored have largely just been variations of Burroughs, Burrows, and Borrows. But when we look at the documents of Peanut’s two statements, neither of them put an “S” at the end of his name. He’s Joseph Burrough in the first one, and John Bohrar is the second. So, where is the ending S coming from? The answer, I think, is the trial transcript.

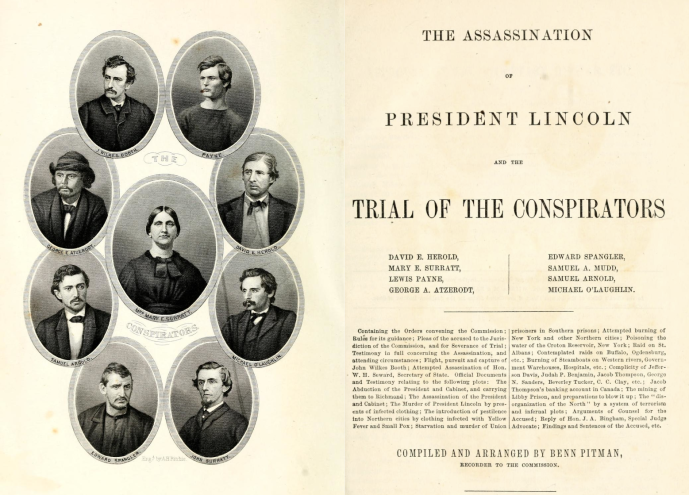

It was quite an undertaking to document the trial of the Lincoln conspirators. It was the duty of several court reporters to take down every word spoken in the courtroom by the commissioners, lawyers, and 347 unique witnesses. The court reporters listened to the words spoken in the trial room and took them down in shorthand. Between each session, the group would then painstakingly translate their notes into longhand and provide a transcript to the commissioners and lawyers the next day. They also provided copies to the newspapers for them to publish the trial, usually a day or two behind. As impressive as this system was, it wasn’t perfect. The shorthand process was done phonetically. Rather than taking down complete words or ideas, the different phonemes, or sounds, of words were taken down and then later transcribed. While this system worked well for much of the trial, one area where it caused mistakes was the spelling of names. When I completed my Trial Project a few years ago, completely documenting and summarizing the conspiracy trial into an easy-to-digest annotated form, the biggest bumps in the road were trying to determine the actual names and spelling of several witnesses.

For example, two of the Ford’s Theatre employees, Jake Rittersbach and John Selecman, are given the names of Ritterspaugh and Sleichmann in the trial transcript. Dr. William Boarman is Dr. William “Bowman,” John Cantley is John “Cantlin,” and William Keilholtz is William “Keilotz,” just to name a few more.

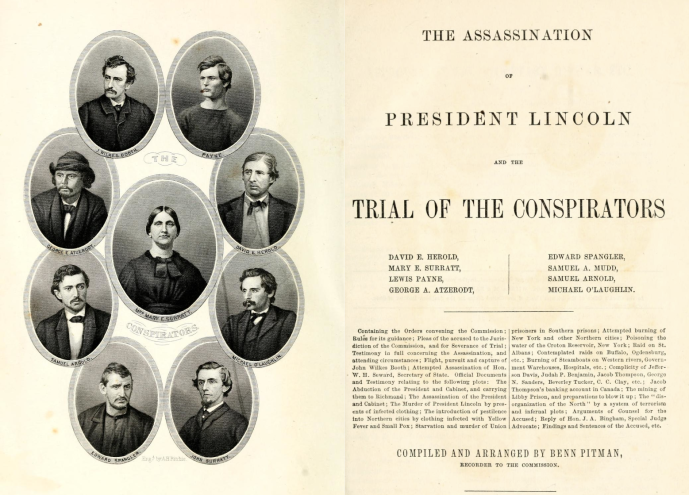

Different versions of the trial transcript exist. Benn Pitman published the “official” version of the trial as a single-volume book. He did this by essentially rewriting witness testimony into long paragraphs of text rather than the actual question-and-answer format that occurred when the lawyers were asking their questions to each witness. Because so much of the original content was taken out to reduce the trial to a single volume, the Pitman version is the least reliable trial transcript. But it is also the most well-known and widely available version. In the Pitman version, Peanut John’s name is given as Joseph Burroughs (with an S). The prevalence of Pitman’s transcript is probably why we have come to accept Peanut’s name to be Joseph Burroughs. However, given the numerous naming mistakes that occurred during the trial, we should be cautious about trusting this spelling, especially given the fact that neither of Peanut’s two statements put an S at the end of his name.

You may be thinking, “So what? Burrough or Burroughs, how does that help us?” Well, the reason I’m going into this is that I think the S has thrown us off. We’ve been looking for a Burrough/Borrow-like name that ends with an S, actively discounting any options without it. But if we free ourselves from the assumption that Peanut’s name has to end with an S, then there is an option that we have overlooked. It’s a small variation of the name given on the second interview Peanut did with the authorities. Let’s explore the possibility that Peanut John’s last name was actually Bohrer.

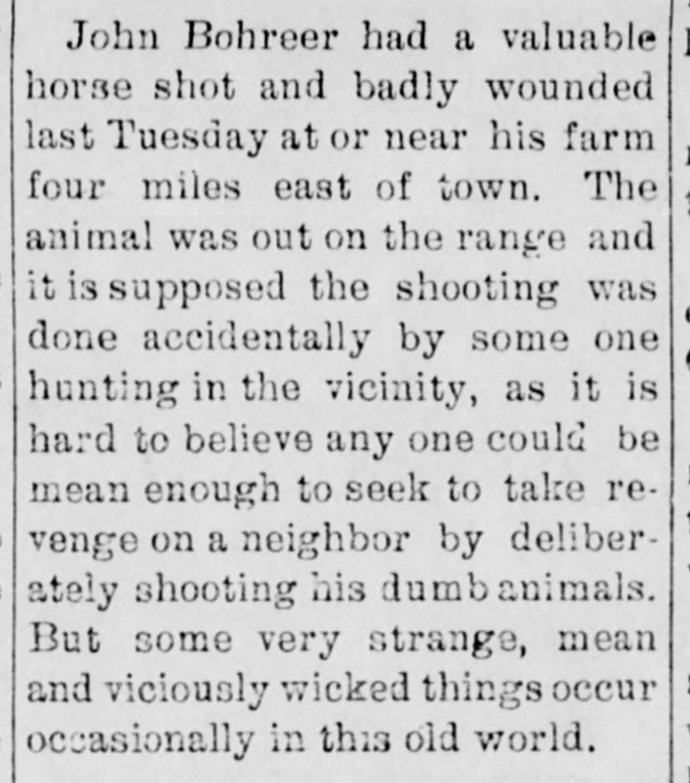

Aside from Peanut’s second interview with authorities on April 24, another piece of evidence that contributes to the speculation that Peanut’s last name might have been Bohrer is an article that was published in the D.C. Evening Star newspaper in 1928. The article recounted how a 1865 police report book had recently been unearthed from “a mass of debris in the subbasement of the Municipal Building.” The book contained handwritten logs from the Metropolitan Police Force from the time of Lincoln’s assassination. It describes some of the items that the police force took possession of after the assassination, as well as a list of those who came into the station to make reports in the hours after Lincoln was shot. This logbook also documented the aforementioned arrest of Edman Spangler and the bringing in of “John Borer (or Burrough) known around the opera house as ‘Peanut John.’” While the name isn’t a perfect match, it is another period document showing a last name without an S that is tantalizingly close to Bohrer.

Bohrer is a German name and, phonetically speaking, is not that far removed from a reasonable pronunciation of Burrough. Given that the Bohrar and Burrough spellings were both used in recording Peanut’s statements, we know that the way he pronounced his name had elements of each. Bohrer is a unique last name, but not an unheard-of one in the Washington, D.C. area. Various Bohrers had lived in the region for many years.

One of the Bohrers who lived in the area was named Benjamin Schenckmyer Bohrer. He was born in Montgomery County, Maryland, in 1788, but moved to the then-independent city of Georgetown (now a neighborhood of D.C.), where he attended school and became a doctor. Except for a few years when he acted as a medical professor at Ohio Medical College in Cincinnati, Dr. Bohrer spent most of his life caring for the residents of Georgetown. In 1835, Dr. Bohrer was called to examine Richard Lawrence, the house painter who had attempted to assassinate President Andrew Jackson. Dr. Bohrer testified that he felt that Lawrence was “totally deranged” on the subject of President Jackson. Partly due to testimony from Dr. Bohrer and other medical professionals, Lawrence was found not guilty by reason of insanity for his attempted attack on President Jackson. Lawrence was committed to various institutions, eventually making his way to the Government Hospital for the Insane, later renamed to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Dr. Bohrer had helped establish this hospital. Dr. Bohrer died in 1862 and his death was greatly lamented in Georgetown, where he had been celebrated for ministering to “three generations in many families in the ancient town.”

Dr. Bohrer and his wife, Eliza Virginia Loughborough, had six children. One of the Bohrer sons was Benjamin Rush Bohrer, born about 1823. In order to avoid confusion with his physician father, Benjamin Jr. often went by his middle name of Rush or by his initials B. R. Bohrer. For a few years, this younger Bohrer ran a livery in Georgetown, renting out horses, buggies, and carriages to his neighbors. In 1848, Rush married Margaret Loretta Sullivan, a Maryland native. The couple had three children together, two of whom were born in D.C. The youngest child was born in Ottumwa, Iowa, where the couple had relocated for unknown reasons. It appears that it was in Iowa that Rush and Margaret’s marriage ended. In 1856, Margaret remarried a widower named Rudolph Bollinger and not long after moved to Brown County, Kansas. In the 1860 Federal Census, Margaret and her three children by Rush are shown living with their mom and stepfather in Claytonville, Kansas. Rush Bohrer had returned to Georgetown and was residing with his father, the doctor, who died two years later.

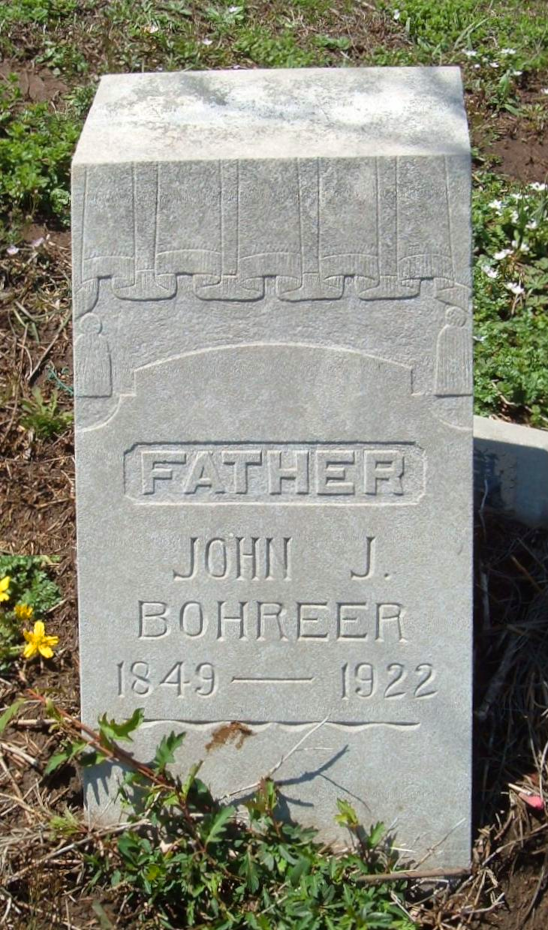

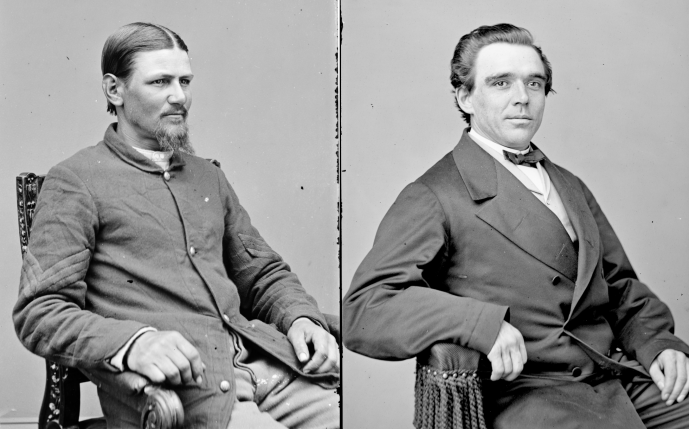

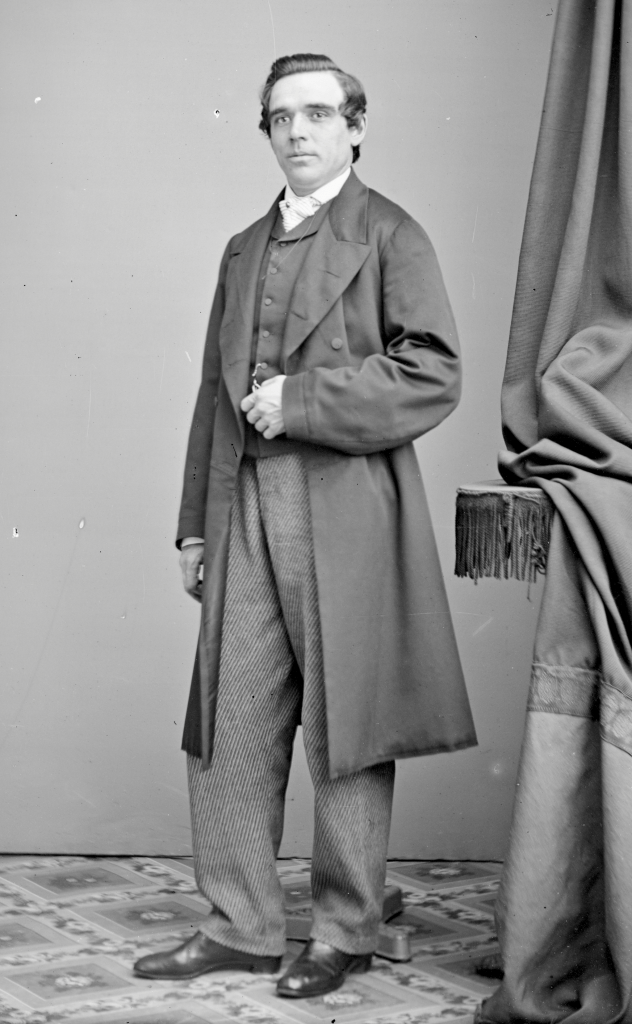

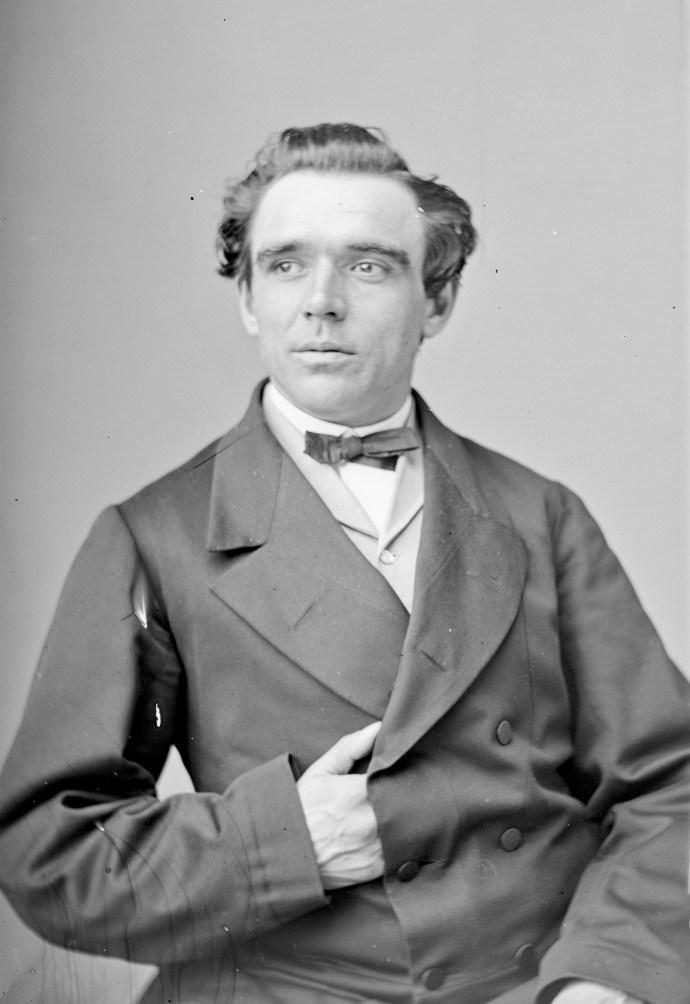

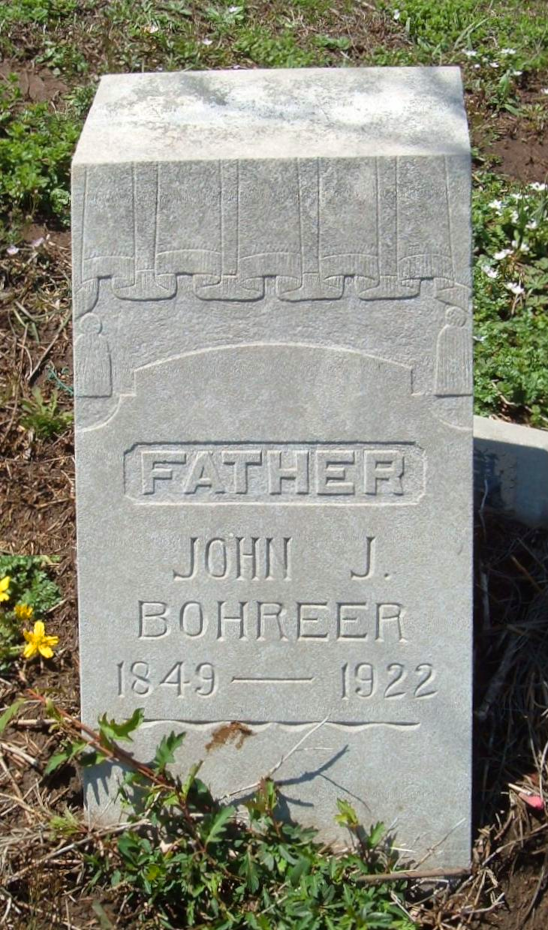

You may wonder why I’ve chosen to share all of these details about these particular Bohrers. Well, it’s because of my own theory that Peanut John might actually be the middle child of Benjamin Rush Bohrer and Margaret Loretta Sullivan. His name was John Jeremiah Bohrer, and this is a picture of him as he would have appeared at about the time of Lincoln’s death.

John Jeremiah Bohrer was the middle child of Rush and Margaret Bohrer. He was born on October 17, 1849, in Washington, D.C. As noted, John’s parents split up when he was young, and he seemingly resided with his mother and stepfather in the years after his parents’ divorce. In September of 1865, John’s name can be found in the Kansas state census, residing with his mother, stepfather, younger brother, and stepsiblings in Brown County, Kansas. In 1875, John married Susan Blackburn in Eufaula, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Susan was a member of the Choctaw Nation, being 1/16 Choctaw according to records. John Bohrer had likely made his way from Kansas to Indian Territory via the newly consolidated Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway. He and Susan made their residence in the Choctaw Nation. They had six children together. At some point, John changed the spelling of his last name to Bohreer. All of John and Susan’s children were given the last name of Bohreer. Susan died in 1903, leaving John a widower. Oklahoma became a state in 1907, and the former Choctaw land on which John Bohreer had lived since about 1874 became part of Pittsburg County. In 1909, John married Mary Lynch, a widow 25 years his junior. John and Mary had two children together.

For the vast majority of his adult life, John Jeremiah Bohreer worked as a farmer, residing within a mile and a half of the same tract of land in Pittsburg County, Oklahoma. When he died on May 8, 1922, at the age of 72, he was remembered as one of the pioneers in the region, “beloved and respected by all.”

Now, I want to reiterate that I’m merely speculating that John J. Bohre[e]r might have been Peanut John. Much like Michael Kauffman’s theory about Peanut John being the son of Dr. Joseph Borrows, or Steve Williams’ exploration of the Joseph A. Burroughs who lived in Tenlytown, I can’t prove it. And, like those other examples, my theory also has issues. Still, here’s my speculative case.

1. He’s around the right age

John Jeremiah Bohrer was born in October of 1849. This would have made him 15 years old at the time of Lincoln’s assassination. William Kent, the witness who swore to Peanut’s X on his first statement, later estimated that Peanut was about 17 years old when he interacted with him. Bohrer’s age puts him right in the sweet spot and would have made other boys like David Finney and Frank Drake his peers.

2. His parents were not together

On the statement where Peanut’s name is given as “John C. Bohrar” it states that he is “living with his father.” At the time of Lincoln’s assassination, John Bohrer’s parents were divorced and living in different states. His mother, Margaret Bollinger, resided in Kansas while his father, Benjamin Rush Bohrer, was living in Georgetown.

3. John Bohrer changed his last name

As noted, John changed the spelling of his last name from Bohrer to Bohreer (which changed the pronunciation from Buh-rur to Buh-rear). During my research, I had a conversation with John’s granddaughter. She and the rest of the family are not sure why John changed his last name. Could it have been to distance himself from the history associated with his prior last name?

4. John Bohreer was barely literate

In the first statement Peanut gave, he signed the document with an X, implying that the boy was unable to sign his own name. We took this as evidence that Peanuts was likely illiterate. In the years just before his wife Susan’s death, John Bohreer applied to become a member of the Choctaw Nation through marriage. He did this to ensure land rights for himself and his children. He was granted acceptance into the Choctaw Nation and received several land grants to increase his holdings. Several of the documents associated with his application and land grants are available to view on Ancestry. In these records, it’s clear that someone other than John Bohreer is filling out the paperwork. But Bohreer was required to sign the documents. Here are some examples of his signature:

Bohreer was only in his 50s at the time these documents were signed. The shaky and inconsistent lettering across the signatures implies that he struggled to write his own name. If Bohreer was Peanuts and had spent part of his teenage years working at a theater rather than getting an education, it would make sense that that was the best signature he could give in later life.

5. The real Peanut John vanished after the assassination

Thomas Bogar writes in his book Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination that, after finishing his testimony at the trial of the conspirators, Peanut John, “stepped out of the witness box and out of the pages of history.” The whole reason we are having this discussion is that whoever Peanut John was, he seemingly failed to ever discuss his brush with history after leaving the witness stand. One would think that, in the 160+ years since the death of Lincoln, someone somewhere would have come across a newspaper article in which the real Peanut John told his story. The lack of any such document or account implies that the real Peanut John didn’t want to talk about this event. While Peanut was innocent of knowing what John Wilkes Booth was planning, he still held the assassin’s horse, unknowingly assisting in his escape. According to William Kent’s recollection, when those around Ford’s Theatre learned what Peanuts had done, “the infuriated crowd pounced on the boy, and but for the fact that a police station was a block away he would have been lynched. There were many cries of ‘Hang him.’” Thus, the assassination was an exceedingly traumatic experience for this young man. If I were Peanuts, I would want to get as far away from the scene of the crime as possible, as soon as I could. How much farther away from the event could you get than later moving to the frontier, residing in Indian Territory, and changing your name?

It’s worth mentioning that one of the actors in “Our American Cousin” later commented on the fate of Peanut John. Actress Kate Evans had the small role of Sharpe, the maid, in the last production Lincoln saw. She later moved to Chicago and was interviewed about the tragic events of April 14, 1865, several decades later. In her dated memory, Evans erroneously claimed that “Both Spangler and Peanut John, following the trial of the conspirators, were sent to Dry Tortugas, but [were] subsequently pardoned.” Peanut John was never sent to Fort Jefferson like Edman Spangler.

Of course, there are still a few flaws in my speculation. As noted before, John Bohrer is documented as living in Kansas with his mother in the 1860 Federal Census and the September 1865 state census. This doesn’t preclude the idea that, during the Civil War years, John travelled back to D.C. to live with his father, but I don’t have any records to support this. Another issue is that the statement that says Peanuts was living with his father at the time of the assassination gives the address as “511 Tenth Street.” I have not been able to find a record that places Rush Bohrer at this address. In 1866, he was in the D.C. directory, still living in Georgetown. In 1865, 511 Tenth Street was the home of a woman named Louisa Brent, the widow of Thomas. What connection she may have, if any, with Peanuts or the Bohrers is unknown. In addition, we have the other records that give Peanut’s first name as Joseph, rather than John. I can’t explain that repeated discrepancy if John Jeremiah Bohrer is the real McCoy.

Still, I speculate that John Bohrer could have been Peanut John. Perhaps during the Civil War years, John went to live with his father, Rush Bohrer. Even if they started off in Georgetown, young John would have wanted to explore the capital city. There were horse-drawn buses that made transportation between the two adjacent communities easy and fast. Somehow, during his visits, John became involved in selling peanuts and other concessions at Ford’s Theatre. This eventually led to him taking on more significant roles around the theater, such as carrying playbills around the city and guarding the stage door during performances. Perhaps because of this new job, he lived away from Georgetown and found lodging further down Tenth Street. John eventually became acquainted with the actor John Wilkes Booth and helped care for the stable Edman Spangler had helped construct for him in the alley behind the theater. Then April 14, 1865, came, and John’s life changed forever. After nearly being lynched for holding the assassin’s horse, John provided two statements to the authorities. In May, he testified twice at the trial of the conspirators, answering questions about his former coworker, Edman Spangler. Once his testimony was given and he was free to go, John decided to leave town. He made his way back to his mother and stepfather in Kansas and was enumerated with them in the state census in September. In the 1870s, the now-adult John took the train south from Brown County to Indian Territory. He met a girl, married her, and set up a new life with a new last name on the frontier. He spent the rest of his life as a respected pioneer and settler in what would become Oklahoma, dying in 1922.

Even if John Jeremiah Bohreer isn’t our guy, I think researchers need to start branching beyond the traditional Burroughs/Borrows name when looking for Peanuts. The assumption that his last name must end with an ‘S’ comes from the unreliable trial transcript, whereas the two best sources we have omit an ‘S’ altogether. If we free ourselves from this constraint, who knows how many other folks with similar-sounding names we might be able to find and add to the old Peanut gallery.

Recent Comments