“It is hard to get them all in court”

The Other Reward Offers for John Wilkes Booth’s Capture

By Steven G. Miller

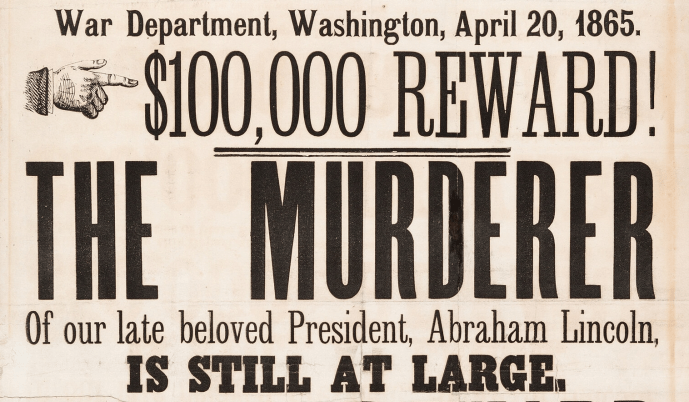

One of the most famous broadsides in American History was the one issued by the War Department on April 20, 1865, announcing a $100,000 reward for the capture of John Wilkes Booth, David Herold, and John H. Surratt. This poster is one of the best-known features of the assassination of President Lincoln, and is easily identifiable by people who know little of the details of Booth’s deed and its aftermath.

One of the least-known aspects of the Lincoln Assassination is the existence, specifics, and disposition of other monetary offers for Booth’s capture. I’ve discovered that there were at least nine of them, and they were made by cities and states from “coast to coast.” All of these offers were repudiated, ignored, or combined with other schemes. The only one that was settled was the one made by the Secretary of War.

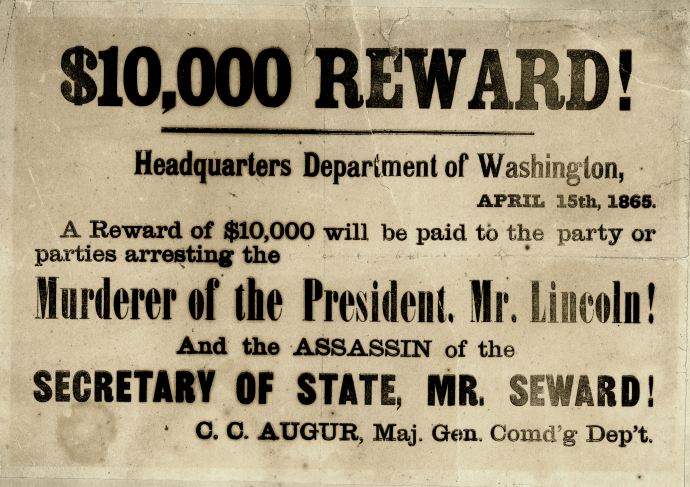

- The first reward offer was made on the 15th of April by General Christopher Columbus Augur, the commander of the Twenty-Second Army Corps, the man in charge of the Defenses of Washington. He proclaimed that $10,000 would be given to the person or persons who aided in the arrest of the assassins.

- Two days later, the Mayor and Common Council of the City of Washington passed “Chapter 274 of the Special Laws of the Council of the City of Washington.” This Act stated: “Be it enacted by the Board of Aldermen and Board of Common Council of the City of Washington, that the Mayor be, and he is hereby authorized and requested to offer a reward of twenty thousand dollars for the arrest and conviction of the person or persons who were concerned in the assassination of President Lincoln, and attempted murder of Secretary Seward and family on the evening of the 14th inst. Provided that if more than one should be arrested and convicted, then said amount shall be apportioned accordingly. Approved April 17, 1865.”

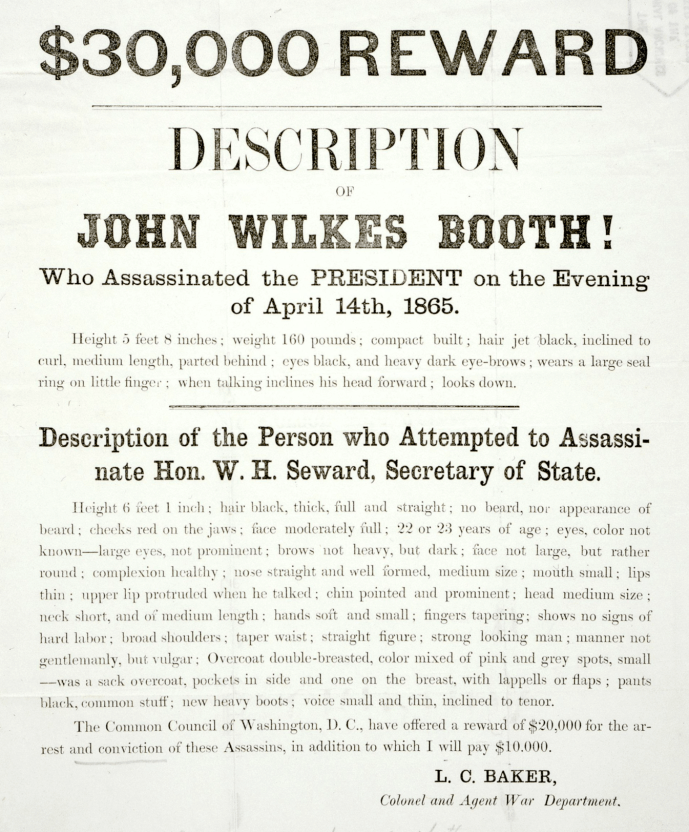

- Later that day, Colonel L.C. Baker, the infamous War Department detective-chief, published a handbill proclaiming a $30,000 Reward. It described John Wilkes Booth and offered a description of the “Person Who Attempted to Assassinate Hon. W.H. Seward, Secretary of State.” As a matter of explanation, Baker stated, “The Common Council of Washington, D.C. have offered a reward of $20,000 for the arrest and conviction of these Assassins, in addition to which I will pay $10,000.”

- On some date unknown—possibly April 17—a $10,000 reward was supposedly offered by the Common Council of Philadelphia.

- The City Council of Baltimore also offered $10,000 for the arrest of the assassin, a former hometown boy. An untitled squib, in the Davenport (IA) Daily Gazette, April 19, 1865, commented on the offer saying, “The feeling here (Baltimore) against Booth is greatly intensified by the fact that he is a Baltimorean, and it is desired by the people that one who has so dishonored the family should meet with speedy justice.”

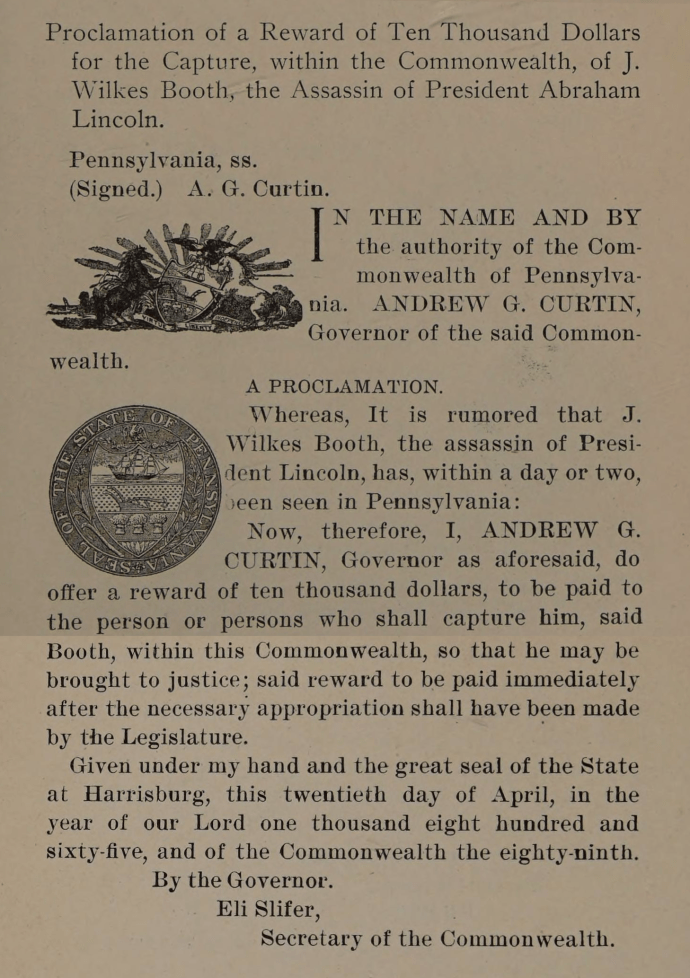

- On April 20th, Governor A.G. Curtin of Pennsylvania announced $10,000 for the capture of the assassin. However, this offer had a catch: the assassin had to be arrested on Pennsylvania soil.

- On April 20, Edwin Stanton published his famous $100,000 reward, offering sums of $50,000 for Booth and $25,000 each for David Herold and John Surratt. A version of Stanton’s reward poster even had photos of the three major conspirators attached. Since this was in the days before the technique of printing halftone photos was developed, photographic prints of the three suspects were actually glued onto the printed piece. This is reportedly the first time actual photographs were added to a wanted poster. Copies of this broadside were distributed throughout Maryland and carried by search parties. The poster was also “re-composed” (re-typeset, in other words) and reprinted in New York City.

- On some unspecified date, the State of California offered $100,000 in gold to the captors. The claim agents for Private Emory Parady, one of the captors of Booth and Herold, contacted the California officials, but nothing came of it, and nothing specific is known about this offer.

- New York State supposedly offered a reward, too. Details are sketchy, but John Millington, another of the Garrett’s Farm patrol members, mentioned this in a 1913 letter to the National Tribune.

Most of these proposals died a quiet death and were forgotten in the aftermath of the arrest, trial, and execution of the conspirators. But attorneys pursued the offers made by the City of Baltimore, and the Washington City.

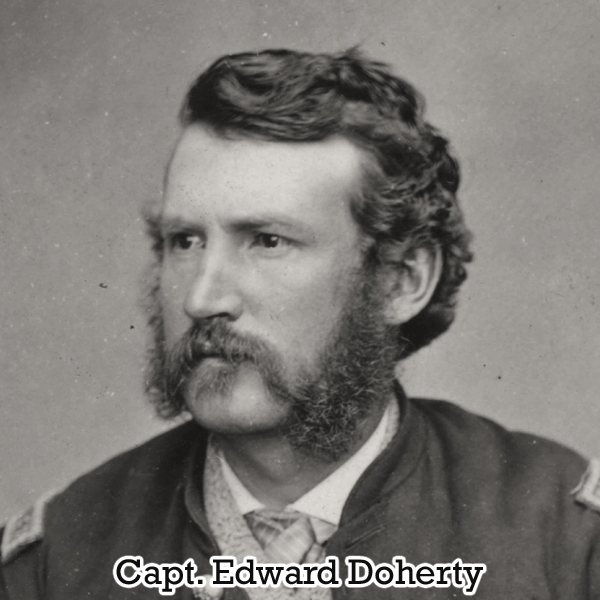

The Baltimore effort ended quickly. An article headlined “Capt. Doherty’s Story” in the August 22, 1879, New York Times explained what happened: “In the case of the claim against the City of Baltimore, which offered $30,000 {sic, should be $10,000} for the arrest of the assassin, Capt. Doherty did not sue to recover, the Mayor and Aldermen telling him point blank that they would not pay it, as the reward was offered under a previous administration. The claim has now lapsed by limitation.”

On November 24, 1865, the War Department issued “General Order No. 64”, which announced that a special commission would be set up to determine the validity of claims for the Reward and that all applications for a share had to be submitted by the end of the year.

It also announced that any other offered rewards were withdrawn. This applied to the $25,000 reward offered for John H. Surratt, who was still a fugitive, and to other amounts posted for members of the so-called Confederate “Canadian Cabinet.” When the final report of the commission was issued, the offers by General Augur and Colonel Baker had been incorporated into the Stanton offer of April 20th.

There was a great deal of wrangling involved in the settlement of the War Department $100,000 offer (as detailed in my article “Were The War Department Rewards Ever Paid?” February 1994, Surratt Courier), but that was minor as compared to the struggle over the reward offered by the officials of the City of Washington. A lawsuit was filed by the three National Detective Police officers in an effort to get the city fathers to live up to their promise. This fight involved a huge cast of characters and dragged on for over a dozen years. It took so long, in fact, that by the time it started moving through the courts, one of the major players was dead.

Here’s the story of that case:

On October 10, 1866, an equity case was filed in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia in General Term by the three detectives and their attorneys. It was designated case “No. 790” and was known as “L.C. Baker, E.J. Conger and L.B. Baker v. The City of Washington, et al.” There were forty-six individuals involved in the suit, all of whom had gotten shares of the War Department reward for the capture of Booth, Herold, Atzerodt, and Payne. The stated purpose of the case was: “For Distribution of the Reward offered by the City of Washington for Assassins of Abraham Lincoln, President of the U.S.”

As I pointed out in my earlier article, the troopers of the Garrett’s Farm patrol monitored the progress of the suit. One of the men who captured Booth, former private Emory Parady, received periodic progress reports from his agents, attorneys Owen & Wilson of Washington. On December 26, 1866, for instance, they wrote: “The suit on the city is progressing — there are so many parties it is hard to get them all in court so we can try. Capt. Dougherty is in North Carolina & we have not got service upon him and there are several others of the same character. When they are all properly before the Court we shall call it up & have it tried.”

The filing of motions, gathering and introduction of affidavits took the rest of 1866, 1867, and all of 1868. During this process, one of the prime movers, Col. Lafayette C. Baker, died in Philadelphia on July 3, 1868. Finally, all of the papers were submitted, and the Court took the matter under consideration. On April 20, 1869, the D.C. Supreme Court announced their verdict. They dismissed the case against the City, ordering that the plaintiffs pay the court costs.

The decision was appealed. On April 25, 1870, a re-argument of the case was granted by a Special Term of the D.C. Supreme Court. On September 29, 1870, the court received an “Amended Answer of the Mayor & Board of Aldermen & Common Council – motion for leave to file made in the Court sitting in General Term.”

The New York Herald summed up the case in an article on September 30th. There were several plaintiffs, the Herald said; the three detectives, Capt. Doherty, attorneys representing the 26 soldiers of the Garrett’s Farm patrol, and three civilians involved in the planning or capture of Mrs. Surratt and Louis Powell. The Herald laid out the positions of the various parties pretty clearly: The attorney for the Corporation of Washington opined that the City had had no authority to offer the reward, and that “the parties claiming this reward did nothing more than, as good citizens, they should have done.” He also stated that they were merely following the orders of their officers.

The counsel for Prentiss M. Clark, one of the civilians involved in the Mary Surratt arrest, stated that police, detectives, and soldiers had no claim since they were only doing their normal duties. By this argument, then, only civilians who gave evidence would be entitled to a chunk of the reward. (Clark was a mere civilian at the time of the arrest, naturally.)

The attorney for the troopers responded that it was not part of their duty as soldiers to assist in the capture of offenders against the law, and, besides, they were not subject to any orders from the officials of Washington City.

In the official documents of the case, counsel for the defendants stated that “the Mayor, Board of alderman and Board of Common Council of the City of Washington did not and do not possess any legal authority to offer or to pay out of the monies of the tax payers of said city any sum whatsoever for the purposes mentioned in the (1865) ordinance.”

Edward Doherty responded with evidence that the mayor had issued a Message on June 30, 1868, indicating that he would seek permission from Congress (which then, as now, governed the District and Washington City) to raise $550,000 in bonds. These were to pay city debts. One of the debts specifically mentioned in the message by the mayor was the $20,000 reward, Doherty noted.

On October 15, 1870, the Special term of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia dismissed the appeal. They found in favor of the City of Washington, et al, and against Stedpole (the executor of the estate of L.C. Baker, deceased), et al.

A long period of silence ensued, but on October 12, 1875, an appeal was filed with the United States Supreme Court. The two individuals who put up the $550 bond for the filing were Prentiss Clark and George F. Robinson, the attendant who helped save Secretary William Seward’s life in 1865.

The appeal was labeled Case No. 691. Which was soon changed to case number 441, and then to 200. It was placed on the docket for October Term 1877, but not called. It carried over to October Term 1878.

The High Court finally dealt with it, but not in a way that the plaintiffs hoped: on November 15, 1878, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the appeal “dismissed with costs” and ordered that the defendants get their costs from the complainants.

In the end, only the War Department paid any reward for the capture of the assassins of President Lincoln. In 1898, former Pvt. John W. Millington summed up the situation to a reporter in Sioux City, Iowa. The journalist stated: “Other rewards had been offered by different states, but Mr. Millington never saw any part of them and long ago came to the conclusion that most of them were in the nature of ‘grand stand plays’.”

Sources:

Boston Corbett-George A. Huron Papers, Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas

“Lafayette C. Baker, Everton J. Conger and Luther B. Baker, v. City of Washington, et al,” Equity docket, Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, Equity Case 790, National Archives, Washington.

Miller, Steven G., “Were The War Department Rewards Ever Paid?” February 1994, Surratt Courier.

The Millington-Parady Papers, Steven G. Miller Collection.

“One of Booth’s Captors,” National Tribune (Washington, DC), June 26, 1913. (John Millington “wants to know why” the rewards offered by the governors of New York and Pennsylvania were never paid.)

“The Reward for the Discovery of the Lincoln Assassins,” New York Herald, September 30, 1870.

“Thirty-Three Years Ago. Anniversary of the Assassination of Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth. A Resident of Sioux City Who Assisted in the Capture of the Murderer. Story of the Pursuit and the Final Scene When He Refused to Be Taken Alive and Was Shot,” The Sioux City (IA) Times, April 14, 1898.

I’m grateful to my friend Steve Miller for allowing me to republish this very interesting article he wrote about the rewards offered for the capture of John Wilkes Booth. This article was originally published in the September 2006 edition of the Surratt Courier.

Great article, Steve! I had no idea there were so many. Are there any other broadsides besides the images you included? Or, were those reward offers simply announced in newspapers?

BTW, you can view one of L.C. Baker’s original $30K reward notices in Albert G. Riddle’s papers at the Western Reserve Research Library in Cleveland. Riddle was Baker’s attorney, the attorney for many of the reward claimants, and also helped the State Department in its trial against John Surratt. WRT the latter, he got conned by Charles Dunham (aka Sanford Conover) in trying to implicate President Johnson.

The library is near James Garfield’s incredible tomb, which is a must-visit. (Riddle’s papers have fascinating Garfield items as well.)

Joe,

It was your exploration of the A.G. Riddle papers at the Western Reserve Library that led to me asking Steve if I could republish this article. A couple days ago, I finally read through all of the original handwritten testimony that you shared with me months ago from Riddle’s depositions of Doherty, the Bakers, Conger, O’Beirne, John Garrett, and Stanton. I had questions about the timeline of this specific suit so I ended up calling Steve to ask him about. Being the gentleman and the scholar that he is, he sent me this article he wrote back in 2006. I then asked him if I could reprint it, to which he agreed. The original article in the Courier didn’t have any pictures so I did my best to illustrate it with the different broadsides I had images of. I just now added a page showing the Pennsylvania reward, but I’m not sure if posters exists of the others.

That’s a great image. I can only imagine the anguish for Gov Curtin, with all his efforts to whisk president-elect Lincoln through Harrisburg in the train decoy ruse in 1861, only to receive his coffin by funeral train in the same location in 1865.

An excellent and interesting article. Thank you for republishing it. Ken

see my pic below of jwb sitting with his little diary clearly showing near the end of the table.. be sure to click on pic to see it close up. i actually own that table.

Do tell the story of acquiring the table!

its a long story and i couldn’t prove anything even if i wanted to… i just love owning it and the small book is the diary.. not the open large book you see on the table.. but there it is just laying there and i hope you can see the one i’m talking about.. i don’t know how to send an enlarged pic of it.. there is also a glass of wine? on the other end of the table.. wow, several different wine glass stains are even on the table exactly where the wine glass is sitting in the pic.. i love jwb’s table.!