I conducted reviews of the seven-part AppleTV+ miniseries Manhunt, named after the Lincoln assassination book by James L. Swanson and released in 2024. This is my historical review for the seventh episode of the series “The Final Act.” This analysis of some of the fact vs. fiction in this episode contains spoilers. To read my other reviews, please visit the Manhunt Reviews page.

Episode 7: The Final Act

The final episode of the series opens with a flashback to 1862. Edwin Stanton attends a party at the White House thrown by the Lincolns. The first family is concerned about the poor health of their son Willie, who will soon die from typhoid fever. Stanton agrees to take over as Lincoln’s Secretary of War.

We then flash forward to the first day of the trial of the conspirators. Stanton talks with reporters outside before seating himself to watch the proceedings. Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt lays out the charges against the conspirators who are seated on a bench in the front of the courtroom. When Holt announces that the government is also charging Jefferson Davis in Lincoln’s assassination, audible gasps and rumblings are heard throughout the courtroom.

Next, we see Stanton talking to Jefferson Davis in his prison cell. The Confederate president denies any involvement in Lincoln’s death and is defiant that the cause of the Confederacy will live on.

In the War Department, Stanton and Holt ask Lafayette Baker what evidence his agent, Sandford Conover, has implicating Davis. Baker admits that Conover has been two-timing them and has also been acting as an agent for the Confederacy. However, Baker plays this as good news as the Confederate Secret Service now knows that Conover has betrayed them and he is now willing to tell everything he knows. Among the information Conover now wants to share is a letter the CSS calls “the pet letter.” Baker tells the men that “pet” was Jefferson Davis’s nickname for Booth, and Stanton announces that Conover will now be their star witness.

There is a brief scene of Holt and Stanton working with Mary Simms to prepare her for her time on the witness stand before we return to the trial for a mash-up of testimonies. William Bell testifies about Powell’s attack on the Seward household, Joseph “Peanut John” Burroughs testifies about Edman Spangler’s assistance to Booth at Ford’s Theatre, and Thomas Eckert misrepresents the importance of Booth’s “Confederate” cipher, as instructed by Stanton in the previous episode.

The testimony then turns to Dr. Mudd, with Jeremiah Dyer defending the doctor’s reputation and accusing his servants (Mary Simms) of having been poor. Baptist Washington, having taken a bribe from Dyer in the previous episode, also speaks favorably of Dr. Mudd and accuses Mary Simms of being a liar, much to the distress of Simms, who sits watching the proceedings. Outside of the courtroom, Simms expresses her concern to Stanton that she won’t be enough to put Dr. Mudd away. We then see her talking to her brother, Milo, at the freedmen’s camp, begging him to testify about Mudd’s treatment of him. Milo is hesitant but is next shown in Stanton’s office in the War Department, listening to Stanton explain how important his testimony would be.

After some more talk between the siblings, Milo agrees to testify. As the Simmses prepare to depart, Mary talks with Louis Weichmann, who is also practicing with Stanton for his upcoming testimony against Mary Surratt. Mary Simms gently accuses Weichmann of not saying everything he knows and asks him to back her up on the stand when she states that Dr. Mudd, John Surratt, and John Wilkes Booth all knew each other before the assassination. Also, Sandford Conover arrives at Stanton’s office and produces the “pet letter” described earlier by Lafayette Baker.

We then jump back to the trial where Milo Simms is on the stand, and he recounts having been shot in the leg by Dr. Mudd when he was enslaved by him. Mary Simms then takes the stand and talks about Dr. Mudd’s disloyal sentiments and having harbored Confederate on his farm in 1864. Mary recounts that John Surratt was a common visitor to the farm and that Mudd had known Surratt and Booth before the assassination. When Dr. Mudd’s defense attorney, Gen. Ewing, attempts to discredit Mary, she tells them to ask Louis Weichmann about it.

Weichmann, next on the stand, describes having seen the conspirators in and around Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse. He describes his friendship with John Surratt and how John was often on trips to Montreal and Richmond. Weichmann also defends Mary Simms, acknowledging that he and John Surratt first met John Wilkes Booth through an introduction made by Dr. Mudd.

Then, it’s time for Stanton’s key witness, Sandford Conover. He admits to having worked for both the Union War Department and the Confederate Secret Service, leveraging information on both in order to make a living. Conover states that when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered, the CSS in Montreal received orders from Richmond via John Surratt to set “pet” in motion. Conover claims that Jefferson Davis referred to John Wilkes Booth as his “pet.” He implicates George Sanders in the assassination plot explicitly but states that Sanders did not have confidence that Booth would succeed. Conover then reads part of the “pet letter” addressed to Sanders, which states that “pet has done his job well and old Abe is in hell.”

On cross-examination, Conover admits that he has several other aliases, including James Wallace and Charles Dunham. When asked when he saw Booth, Surratt and Sanders together in Montreal, Conover pauses before giving the date of October 17, 1864. Defense attorney Ewing then counters with a record establishing that Conover was in jail during the month of October. Conover admits his mistake over the date but is adamant that Jefferson Davis knew of and ordered the assassination of Lincoln. After accusing Conover of deliberate perjury, Gen. Ewing rests his defense.

Back at the War Department, Stanton, Mrs. Lincoln, and others await the announcement of verdicts in the case. Mrs. Lincoln tells Stanton he has done well, regardless of the outcome involving Jefferson Davis. Thomas Eckert then gets word that the judges have finished their deliberations, and pretty much the whole cast of characters makes their way back to the courtroom.

General David Hunter, the president of the military commission, first addresses the courtroom, noting his belief that Jefferson Davis is as much guilty of the conspiracy against Lincoln as John Wilkes Booth. However, Hunter states that the commission was unable to conclusively reach a verdict on such a grand conspiracy due to tainted evidence. He leaves it to history to prove the Confederacy’s culpability.

Hunter then turns to the conspirators in the courtroom, all of whom are still standing. He hands the verdicts over to Secretary Stanton to read. Stanton reads through each name and verdict, one at a time. After announcing that Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold have all been found guilty, Hunter interposes with the news that these four will be hanged tomorrow. Stanton then announces Spangler’s guilt and sentence of 6 years in prison. An impatient Mary Simms whispers to Eddie, asking about Mudd seconds before his father declares Mudd guilty and sentences him to life imprisonment. Mary and Milo Simms embrace, and the conspirators are led out of the room.

Outside the courthouse, Lafayette Baker and Edwin Stanton confront Sandford Conover about his faulty testimony. Conover says he told the truth but admits that he had received a suspicious package from London that morning. Baker concludes that George Sanders got to him. In a brief montage, we witness David Herold pulled from his cell, situated on a scaffold, and a rope placed around his neck. He is standing alongside the other condemned conspirators before we cut to a photograph in Stanton’s hand showing the execution.

Thomas Eckert informs Stanton that the National Archives collected the pieces of evidence from the trial but noted that pages from Booth’s diary are missing. Eckert warns Stanton that they might open an inquiry. Stanton lies, saying that Lafayette Baker had the diary last. A knowing Eckert then tells Stanton that he had the secretary’s fireplace cleaned recently, showing his loyalty to his boss, who destroyed the diary pages in that fireplace the episode before.

We flash forward to a future date. Elizabeth Keckley is hosting a fundraiser for the Freedmen’s Bureau by selling copies of a book about her time in the White House. Mary Simms is there and is encouraged to apply to Howard University, a new college for Black Americans. Secretary Stanton speaks favorably of the Freedmen’s Bureau and complains of President Johnson’s lack of support for its mission. To this party, the President arrives, accompanied by General Lorenzo Thomas, an adversary of Stanton’s. Johnson informs Stanton of his intention to remove troops from the Southern states. Knowing that Stanton will oppose him, Johnson tells Stanton that Gen. Thomas will be replacing him as Secretary of War. Stanton notes that trying to remove him will trigger an impeachment investigation by Congress, but President Johnson is unconcerned.

A fuming Stanton offers General Thomas a tour of the War Department. As he shows his replacement around, Stanton recalls a conversation he had with President Lincoln the day before the assassination. Stanton attempted to resign now that the war was coming to a close, but Lincoln denied his request, noting that he needed Stanton more than ever to fight for the future of the nation during Reconstruction. Remembering his promise to Lincoln, Stanton locks his office door and barricades himself into the War Department, determined to preserve Lincoln’s plans for Black suffrage and a united nation.

Through text on the bottom of the screen, we are told that Stanton barricaded himself in the War Department for three months while Andrew Johnson faced impeachment. In the end, Johnson avoided removal from office by a single vote. We also learn that John Surratt was eventually returned to the United States but was not convicted. He is shown giving a speech about his involvement with John Wilkes Booth. Mary Simms is also shown preparing for her first day at Howard University as the text tells about the adoption of the 13th and 14th amendments, which officially ended slavery and granted citizenship to Black Americans.

We then jump to Christmas Eve of 1869. It’s clear Stanton’s asthma has gotten worse over the intervening years as he inhales vapors through a medical device. Eddie Stanton brings news to his father that the elder statesman has been officially confirmed as a new justice of the Supreme Court. The younger Stanton is confident that, as a member of the Supreme Court, his father will continue to ensure Lincoln’s vision for the country and congratulates his father. Even in his weakened state, Stanton is noticeably pleased. After Eddie excuses himself, a teary-eyed Stanton looks out the window and announces, “We finish the work now. We have to.”

However, as the former Secretary attempts to rise from his chair to join his family downstairs for a meal, he becomes weak and collapses back down into his chair. His papers fall to the ground, and we see that Edwin Stanton has died. A voiceover from Eddie Stanton laments his father’s death from asthma-related organ failure before he was able to serve on the court. A similar voiceover from Mary Simms relates the ratification of the 15th Amendment two months after Stanon died. Finally, the series ends with an echo of Stanton’s words that the work still needs to be finished.

Here are some of the things I enjoyed about this episode:

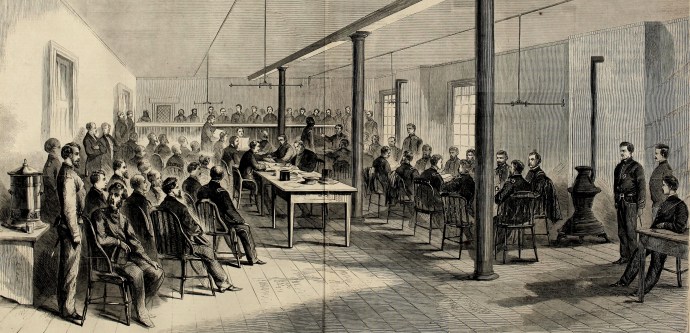

- The Trial Room

As someone who has spent quite a bit of time giving tours to visitors at the trial room of the Lincoln conspirators at Fort Lesley J. McNair, I was impressed with how well the production managed to duplicate the look and layout of the room. The set designers clearly studied the engravings of the trial room that were published in the illustrated newspapers and did their best to recreate them.

For the sake of filming and space, not every detail of the room is the same, but my hat goes off to the crew for this admirable recreation.

- Mary Simms’ Testimony

As I have noted throughout these reviews, the Mary Simms shown in this miniseries is a fictional representation of the real person. Mary Simms had been enslaved by Dr. Mudd but left the farm after emancipation came to Maryland in November of 1864. She was not present at the Mudd farm when John Wilkes Booth stopped there after assassinating Lincoln.

Despite the entirely fictional nature of the Mary Simms shown in this series, the writers actually provide a fairly realistic portrayal of Mary Simms’ trial testimony in this episode. Rather than being asked about Dr. Mudd setting Booth’s broken leg and letting him stay the night (something the real Mary Simms never witnessed, but this fictional one does), Judge Advocate Holt asks Mary about Dr. Mudd’s Confederate sympathies. This is in line with the testimony of the real Mary Simms, who described how a group of Confederate soldiers found refuge at the Mudd farm during the summer of 1864. The real Mary Simms also discussed how John Surratt had been a visitor to the Mudd house, establishing a connection between Mudd and clandestine Confederate activities.

Aside from the ending appeal to the judges to ask Louis Weichmann about the relationship between Booth, Surratt, and Mudd and the claim that she had tried to leave the Mudd farm but couldn’t, the testimony presented by Mary Simms in the series is surprisingly close to accurate. You can read the real Mary Simms’ testimony for yourself here.

- The Ending

I have to give credit to the series for providing an emotional and compelling ending. Watching Stanton fight tooth and nail to protect the dream of a truly unified country in which citizens of all races are treated equally, only to die right after achieving a position where he could make a sizable difference, is heartbreaking and inspiring. In truth, it was clear that the miniseries was always intended to be about Edwin Stanton’s fight with President Johnson over Reconstruction and the Freedmen’s Bureau. You can tell that the writers had so much more that they wanted to include about the fight over Reconstruction and how its failure negatively impacted our nation for a century.

Let’s dig now into the fact vs. fiction of this episode and learn about the true history surrounding these fictional scenes.

1. Stanton (and others) Never Attended the Trial

There’s quite an assortment of familiar faces attending the trial of the conspirators on its first day. In addition to Edwin Stanton, we see Mary Lincoln, William Seward, Fanny Seward, and Lafayette Baker. In reality, none of these people ever visited the conspiracy trial in person.

Secretary Stanton had far more important things to attend to as the head of the War Department to spend his days in the courtroom. He trusted JAG Holt and his assistants to take care of things without his presence. Mary Lincoln would have never entered the courtroom where her husband’s murderers were on trial, though she remained in the White House until about May 23 before departing for Illinois. Tad Lincoln was the other member of the Lincoln family who attended the trial of the conspirators, and he did so on May 18, shortly before leaving the city with his mother. William Seward was still too badly injured by the attempt on his life to have attended the trial. The Secretary of State was forced to wear a mouth splint to heal his broken jaw all the way up to October of 1865. There is no evidence that Fanny Seward attended the trial either, though her brother Augustus Seward did testify about the attack on their father on May 19. While Lafayette Baker took an interest in the trial and even inserted some of his own men to act as guards and keep an eye on things, he never attended the trial himself.

In truth, practically no one attended the trial during the first few days anyway. Stanton had originally ordered the trial to be conducted behind closed doors with no access to the press and public. However, after General Grant testified behind these closed doors on May 12, he visited President Johnson personally and lobbied for the proceedings to be opened to the public for the sake of transparency. Johnson acquiesced and ordered the press and public to be granted access. The first outside visitors were allowed in after lunch on May 13, the fifth day of the trial.

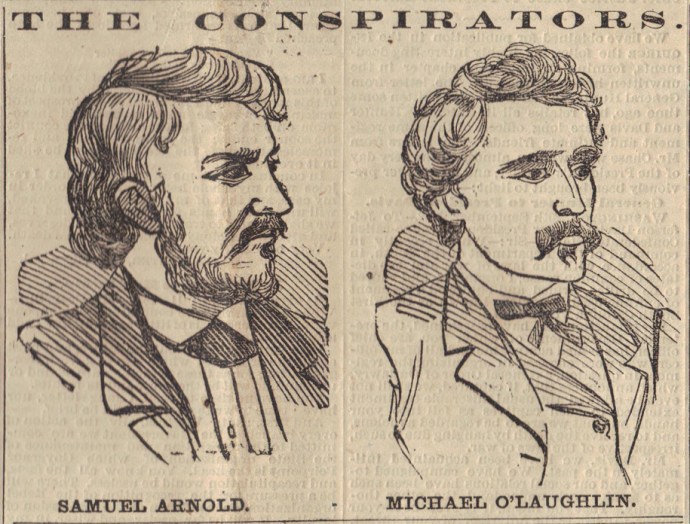

2. The Missing Conspirators

When Joseph Holt is naming off the conspirators on the prisoner’s bench during the first trial scene, there are two noticeable missing faces. These would be the figures of Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen, two of Booth’s childhood friends who took part in the actor’s initial plot to abduct the President but were not actively involved when that plot changed to assassination. The miniseries never really addresses this abduction plot, which ultimately brought all of the conspirators together in the first place. As a result, Arnold and O’Laughlen do not appear at all in the series.

I think it is a bit regrettable to have not included these men, for while they may not have had much to contribute to the manhunt for Booth aspect of the show, a letter written by Arnold to John Wilkes Booth is actually a rare piece of tangible evidence connecting the Confederacy to Booth and his abduction plot. During a search of Booth’s room after the assassination, investigators found a letter written by Arnold to Booth in which Arnold expresses his apprehension in continuing with the abduction plot. Arnold is concerned that the men have waited too long to act and questions whether anything good could now be accomplished by kidnapping Lincoln. It’s essentially a “Dear John” letter with Arnold announcing his intention to bow out of the whole affair.

Arnold includes one intriguing caveat, however. He writes to Booth to “go and see how it will be taken at R—-d, and ere long I shall be better prepared to again be with you.” In short, he tells Booth that if he is able to visit the Confederate capital of Richmond and get their approval for the plot, he would be willing to come back into the fray. Even today, historians point to this letter and Booth’s involvement with Confederate courier John Surratt in their debates regarding how involved the Confederacy may have been with John Wilkes Booth and his plots.

3. The Prisoners’ Dock

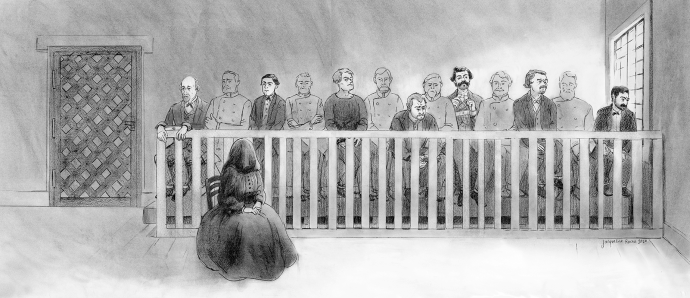

In addition to the absence of Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen, the way in which the conspirators were arranged on the prisoners’ dock during the first day of the trial does not match the actual arrangement. Over the course of the eight-week trial, the conspirators were seated in multiple arrangements. For my project thoroughly documenting the trial of the Lincoln conspirators, I commissioned a talented artist named Jackie Roche to sketch out the different seating arrangements in which the conspirators were placed. Here, again, are those drawings:

May 9 and 10

During the first two days of the trial, both Mary Surratt and Dr. Mudd were placed in chairs in front of the prisoners’ dock. The reason for this was that the bench seating that had been created for the prisoners was not long enough to seat each conspirator with a guard between them. When General Winfield Scott learned that Dr. Mudd had been given a seat outside of the prisoners’ dock, he wrote to General John Hartranft, the commander in charge of the conspirators, asking why Mudd was being given preferential treatment. General Hartranft explained Mudd’s preferential seating was accidental as he and Mrs. Surratt had merely been the last prisoners to enter the courtroom on the first day and were given chairs since there was no more room.

May 11 – 13

In order to prevent the appearance of Dr. Mudd receiving preferential treatment, on May 11, General Hartranft altered the seating arrangement in order to squeeze Dr. Mudd in on the bench. This was done by removing the guard who had been seated between Samuel Arnold and the window and placing Mudd at the other end. The conspirators stayed in this position for the remainder of the first week of the trial while Mrs. Surratt was still seated in a chair in front of the other prisoners.

May 15

On the first day of the second week of trial, Mrs. Surratt was moved to be placed in line with the other conspirators, though she still occupied a chair of her own. A seated guard was also placed between her and the rest of the prisoners. Conflicting accounts also state that Dr. Mudd was moved to a spot between Arnold and Atzerodt on this date.

May 16 – June 17

After the court adjourned on May 15, additional carpentry work was done to extend the prisoners’ dock. A small raised platform was created on the other side of the door through which the conspirators entered and exited. The railing in front of the conspirators was also extended all the way to the wall, with a small gate created near the door. For the bulk of the trial, this was the seating arrangement for the conspirators. Mary Surratt sat on a chair on her small platform with a seated guard in a chair on the floor between her and the long raised bench seating occupied by the men and their guards.

June 19 – 21

During the testimony on June 19, Mrs. Surratt became ill, resulting in an early adjournment for lunch. When the court resumed an hour later, Mrs. Surratt was allowed to sit in a chair in the passageway between the courtroom and one of the adjoining rooms. In this way, Mrs. Surratt had better access to airflow in the hot third-story room. Due to her ill health, this adjoining room became Mrs. Surratt’s new prison cell from that day on. She sat between these two rooms for the next few days when the court was in session.

June 23 – 28

During the final days of the trial, Mrs. Surratt’s condition prevented her from appearing in the courtroom. Instead, she remained behind the closed door in what had become her new cell. She likely listened to the closing proceedings through the door.

You will also note in the drawings that Mrs. Surratt wore a veil throughout her time in the courtroom. While the miniseries shows Mrs. Surratt being forced to wear a hood over her head, she never had to endure the hoods like most of the male conspirators did. Dr. Mudd was the only male conspirator who was also not forced to wear a hood when not in the courtroom. Except for the very first day of trial, the hoods were always removed from the conspirators’ heads before they were filed into the courtroom, as the military judges disliked seeing them.

4. The Testimony Against Spangler

During the testimony portion of the episode, we see the return of Joseph “Peanut John” Burroughs as he bears witness against Edman Spangler. Burroughs recounts how Spangler told him to hold Booth’s horse at the rear of Ford’s Theatre on the night of the assassination. When Burroughs said he couldn’t due to his other duties, Spangler replied threateningly that he didn’t have a choice. Burroughs also swears “on the Bible” that Spangler opened the rear door of the theater for Booth to escape.

While all of Burroughs’ testimony aligns with what was portrayed in the first episode of the series, I just wanted to repeat that the series in no way represents the truth behind Spangler and his supposed culpability in Booth’s crime. It is true that after riding up to the back of Ford’s Theatre Booth asked for Spangler by name to hold his horse and that the stagehand passed the duty off to Peanut John. However, beyond this fact, the series is way off. Rather than threatening Burroughs when the latter mentioned he had his own duties to perform, Spangler told Peanut to lay the blame on him if anyone should object to the young man not being at his normal post. The subsequent idea that Edman Spangler was outside of the theater when the shot occurred and then opened the door for Booth is completely inaccurate. Spangler was carefully tending to his duties backstage and preparing for a scene change when the shot rang out.

Spangler may have been friendly with Booth and done small handyman work for the actor when he visited Ford’s Theatre, but practically all historians agree that Edman Spangler was innocent of any knowledge of Booth’s plot against the President.

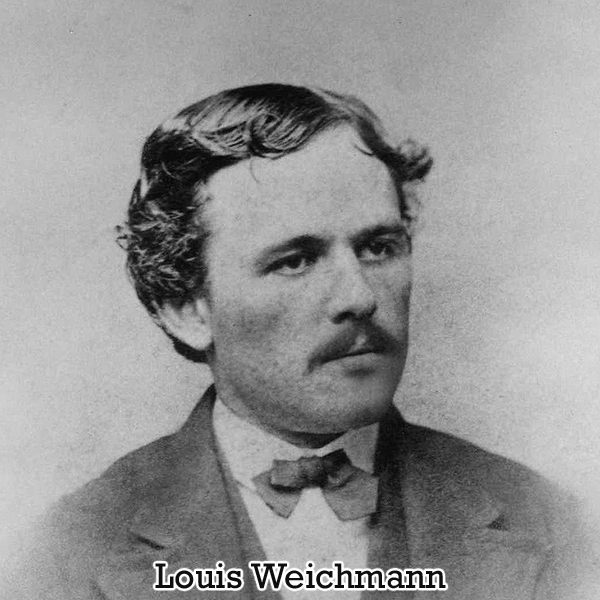

5. Louis Weichmann’s Testimony

Louis Weichmann was a key witness at the trial of the conspirators and testified at length on multiple occasions. His main benefit to the prosecution was to document the movements of some of the conspirators in and around Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse in the time leading up to the assassination.

Weichmann also testified about his introduction to John Wilkes Booth by way of Dr. Mudd. This is the introduction that Mary Simms references in her conversation with Weichmann before the trial and what Weichmann testifies about on the stand. The miniseries has Weichmann state that this introduction occurred in January of 1865, which is what he did testify to at the trial. However, the real Weichmann was mistaken about this date, as the actual day of Booth’s introduction to John Surratt via Dr. Mudd occurred on December 23, 1864. Dr. Mudd’s defense seized upon the discrepancy in Weichmann’s timeline and produced a litany of witnesses to prove that Dr. Mudd did not visit D.C. in January of 1865. While I appreciate that the miniseries had Weichmann swear to January on the stand, the lack of any follow-up muddies the history a bit (no pun intended).

The far more questionable aspect of the miniseries’ portrayal of Weichmann’s testimony, however, is the attempt to add some scandalous drama where it does not exist. When asked about how well he knew John Surratt, Wiechmann states that they had both attended seminary school together and remained close after both had dropped out. Wiechmann recalled how he came to move into Mary Surratt’s D.C. boardinghouse and how he and John Surratt shared a room and a bed. Then, a hesitant Weichmann states that the two men had “slept together,” which draws gasps and murmurs from the crowd, and we are given a shot of Mary Surratt showing her apparently traumatized by the news her son might be a homosexual.

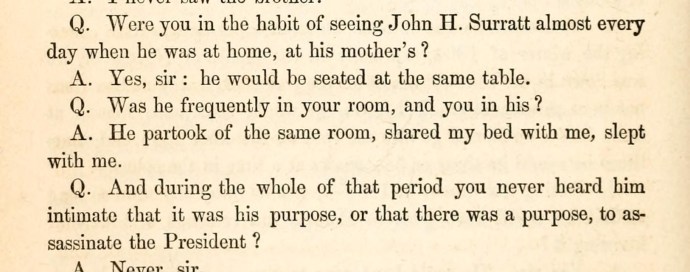

It is true that Weichmann testified about having slept with John Surratt. Here’s that part of his testimony.

However, the idea that Weichmann’s words here are an admission to having a sexual relationship with Surratt is an example of painful historical illiteracy on the part of the writers of this series. The sharing of beds was a very normal part of life during this period of time. Space was at a premium in Washington during this time, especially with the huge influx of visitors and new residents on account of the war. Unless you were wealthy enough to secure truly private lodgings, it was expected that you would share a room and bed with someone else when staying in a boardinghouse or hotel. When you checked into a hotel, you were paid for a spot in a bed, not for your own room. To illustrate this, after George Atzerodt failed to assassinate Vice President Johnson, he eventually took a late-night room at the Pennsylvania House Hotel. The room was already occupied by others, and George merely joined the other male occupants in the bed that night. Men “sleeping with” other men and women “sleeping with” other women was not a euphemism for having sex; it was a common sleeping arrangement that would have been perfectly understood by those living in the 1800s. No one would have gasped or even thought Weichmann was referring to anything sexual during his testimony. This scene, and the implication that Weichmann was testifying against his own lover, is perhaps the cringiest part of the entire series.

6. Sandford Conover’s Testimony

Sandford Conover’s appearance in this trial episode is the only one in which his inclusion makes any historical sense. Despite having been portrayed as an active member of the manhunt over Lincoln’s death, including a trip up to Canada in a failed attempt to snag John Surratt, Conover is little more than a lying footnote in the grand scheme of things. This episode has Conover take the stand, which the real man did three times, including on the last day of testimony. Rather than try and untangle the unique tapestry of partially true and fictitious statements sworn to by the miniseries’ Conover, here’s an excerpt from my trial project documenting the real Conover’s final time on the witness stand. This comes from the June 27 session, the last day in which witnesses testified.

Sandford Conover, a key one of the government’s main perjurers, was recalled to the stand after previously testifying for the prosecution on May 20 and 22nd. During his earlier times on the stand, Conover, whose real name was Charles A. Dunham, claimed that he saw John Wilkes Booth and John Surratt in Canada plotting the assassination of Lincoln with known Confederate agents. His testimony, along with that of James Merritt and Richard Montgomery, was the prosecution’s main evidence that the plot to kill Lincoln had originated with Confederate officials. In 1866, James Merritt would testify before a congressional committee and admit that his testimony had been false. Conover had paid both Merritt and Richard Montgomery to commit perjury. In November of 1866, Conover would be indicted for perjury, found guilty, and sentenced to ten years in prison.

After giving his original perjured testimony in May, Conover returned to Canada where he was known as James Watson Wallace. He was sent there, ostensibly, to uncover more vital information regarding the origins of the plot. While in Canada, Conover’s previously secret and withheld testimony was prematurely published in the press. Though he had been outed as a spy of sorts, Conover/Wallace/Dunham decided to double down on his lies. When confronted in Canada, “Wallace” swore under oath that he had never used the name of Conover and that he had never testified in Washington. He accused “Conover” of impersonating him and denied that he knew Jacob Thompson, one of the Confederate agents that Conover had claimed to have had discussions of Lincoln’s assassinations with, intimately. He also swore then that he never saw John Wilkes Booth in Canada. Wallace went so far in his denials of “Conover’s” testimony that he offered to come to Washington to prove to the commission that he was not Conover and offered a reward of $500 for the capture of the man who had impersonated him. His lies in Canada did not seem to get him as far as his lies in the U.S., however, as by June 16, Wallace was in jail in Montreal, where the newspapers reported, “he now confesses he is Sanford Conover, and wishes to disclose how and by what means he was induced to go to Washington at the instance of Federal pimps for perjury, but that Southerners here scorn to go near him to receive his disclosures.” Not wanting Conover’s arrest and possible confession to perjury to sully his vital testimony at the conspiracy trial, the U.S. War Department arranged for Conover’s release from prison in Montreal and brought him back to D.C. to re-take the stand and explain himself.

Back on the witness stand in Washington and away from Canada, Conover testified on June 27 that the affidavits he swore to in Canada and his offers of reward for the arrest of himself were false. He claimed that Confederate agents confronted him with a pistol to his head when his May testimony at the conspiracy trial was released and that the only reason he swore under oath that he was not Conover was to save his life. Conover also spent a large part of his testimony on June 27 claiming that the official transcript of the trial of the St. Albans raiders did not provide an accurate copy of his testimony and that what he had testified to at this trial was the truth. In reality, very little of what Conover/Wallace/Dunham testified to was truthful. Conover was continuing to lie and perjure himself so that he could keep “investigating” his accusations for the U.S. government in order to milk it of funds. He told the authorities exactly what they wanted to hear in order to stay in their good graces as long as possible. The prosecution’s insistence on sticking by Sandford Conover even after the evidence of his perjury was made known demonstrates how the Judge Advocate General was willing to “use tainted evidence to gain his ends.”

To be fair to the miniseries, Conover still comes across as unreliable and shifty by the end of this episode, even if the writers did make it seem like he was being threatened by the boogie man of George Sanders to justify his failure to deliver on his promises.

7. The Pet Letter

Much is made about “the pet letter” in this episode. It is first hinted at by Lafayette Baker, who portrays it as definitive proof that Jefferson Davis authorized his “pet,” John Wilkes Booth, to kill the president. When Sandford Conover reappears in Stanton’s office, the Secretary of War hungrily reads the letter that Conover has recovered from the Confederate Secret Service. During the trial, Conover claimed that the letter was addressed to George Sanders but that he never picked it up. From the way the miniseries talks about it, this “pet letter” seems to be one of the most important pieces of evidence at the trial.

In reality, however, the “pet letter” was not connected to either George Sanders or Jefferson Davis and is just another example of how the prosecution was so desperate to connect Booth to the Confederacy that they brought forth the most spurious pieces of evidence available. Here is an explanation of the “pet letter” from my trial project. This first section is from June 5, when the letter was first entered into evidence.

Charles Deuel, a member of the Construction Corps, Railroad Department, testified that he had been working in Morehead City, North Carolina, during the month of May. On May 2nd, while he and another man named James Ferguson were near the government wharf in that city, he noticed a letter floating in the water. He picked it up and discovered it was written in code. Deuel stated that through a little trial and error, he managed to decode the note. The letter was supposedly dated April 15th and was in an envelope bearing the name John W. Wise. The letter spoke of the work “Pet” had done well and that “Old Abe” was now dead. The writer lamented that “Red Shoes” lacked nerve in “Seward’s case.” The writer also appealed to the intended recipient to “bring Sherman” and commanded them not to “lose your nerve.” The letter continued in a coded, conspiratorial fashion and was ultimately signed by “No. Five”. At this point, the defense had very few questions about the letter as they deemed it unrelated to their clients’ cases and assumed the government was admitting it in the same manner they had presented evidence against the Confederate government. Only Frederick Aiken cross-examined Deuel, asking how he decoded the letter and whether the original letter had suffered a great deal of blurring from being found in the water. Deuel stated his belief that it did not appear to have been in the water long and was, therefore, not blurred. In his book, The Lincoln Assassination Encyclopedia, author Edward Steers, Jr. states that “The letter appears to be a fabrication, but by whom and for what purpose is not clear.” Later, on June 7th, Thomas Ewing would make a motion to have this cipher letter stricken from the record.

The coded letter, found in the water in Morehead City, NC, was entered into evidence as Exhibit 79.

James Ferguson, a laborer working under the previous witness, Charles Deuel, testified that he was with Deuel in Morehead City, NC. Ferguson claimed he was the one who noticed the letter in the water and called it to the attention of Deuel, who retrieved it. Ferguson identified the letter submitted into evidence as the same one he had seen.

So the “pet letter” was a random coded letter found in the waters of Morehead City, North Carolina, on May 2, 1865. It was addressed to a “John W. Wise” and appeared to make references to the assassination of Lincoln. Here is the full, decoded “pet letter” for more context:

“WASHINGTON, April the 15, ’65.

DEAR JOHN,

I am happy to inform you that Pet has done his work well. He is safe, and Old Abe is in hell. Now, sir, All eyes are on you. You must bring Sherman: Grant is in the hands of Old Gray ere this. Red Shoes showed lack of nerve in Seward’s case, but fell back in good order. Johnson must come. Old Crook has him in charge.

Mind well that brother’s oath, and you will have no difficulty; all will be safe, and enjoy the fruit of our labors.

We had a large meeting last night. All were being in carrying out the programme to the letter. The rails are laid for

safe exit. Old — always behind, lost the pop at City Point.Now I say again, the lives of our brave officers, and the life of the South, depends upon the carrying this programme into effect. No. Two will give you this. It’s ordered no more letters shall be sent by mail. When you write, sign no real name, and send by some of our friends who are coming home. We want you to write us how the news was received there. We receive great encouragement from all quarters. I hope there will be no getting weak in the knees. I was in Baltimore yesterday. Pet had not got there yet. Your folks are well, and have heard from you. Don’t lose your nerve.

O. B.

No. Five.”

As was seen, the defense attorneys didn’t have much to say about the “pet letter” when it was first entered into evidence. However, that changed two days later, on June 7, when one of the defense attorneys decided to bring the matter back up:

Defense lawyer Thomas Ewing then made a motion that the cipher letter found in the waters of Morehead City, NC, and entered into evidence on June 5th be stricken from the record. Ewing explained that he had been absent from the courtroom at the time the cipher letter was introduced after being assured that the testimony concerning it would only deal with the larger Confederate conspiracy the government was pursuing. It was only after seeing the record concerning the cipher this morning that Ewing learned more about it. Ewing stated his belief that the cipher was undoubtedly fictitious, and even if the prosecution thought otherwise, it was still wholly inadmissible under the rules of evidence. As Ewing noted, the note was not signed, its handwriting was not proven to be one of the conspirators, it was not shown to be connected to any of the conspirators, nor was it in the possession of any of the conspirators. Ewing stated that the cipher was the declaration of an unknown person not shown to be connected in this conspiracy, and, therefore, the letter was as unconnected with this case as “the loosest newspaper paragraph that could be picked up anywhere.”

Assistant Judge Advocate John Bingham countered that part of the charge and specification against the eight conspirators now on trial was that they had entered into a conspiracy with parties named and others unknown. Bingham then went into a long description of the evidence already presented, which formed the foundation for the admission of this cipher. In the end, he stated that this letter was proof of the additional unknown conspirators the charge and specification spoke about. Ewing replied that for such a letter to be admissible, it would have to be proven to have been written by a co-conspirator. Bingham stated that based on the other proofs in the case, the prosecution believed that this cipher was written by an otherwise unknown co-conspirator.

Walter Cox, the lawyer for Michael O’Laughlen, then joined Thomas Ewing in his motion against the cipher. He reiterated that, originally, the defense team had no objections to the letter because they were under the impression that it would relate to the machinations of agents in Canada with possible connections to authorities in Richmond. Cox made it clear that the defense had never opposed testimony of this kind in order to ferret out the truth. They merely wished to show that their own clients had no involvement with any such Confederate plans. The defense, therefore, did not preview this cipher before it was read into court. After it was read, however, and it was purported to have been written by someone immediately connected with the assassination, that changed the nature of the evidence. Cox agreed that the law allowed the declaration of one conspirator to be used against another conspirator, but he insisted, like Ewing, that the connection must first be made showing that the alleged conspirator making the declaration is actually connected to the conspiracy. Until other evidence proved the author of the cipher’s connection to the conspiracy, Cox stated that it was inadmissible to use it as evidence. Cox reiterated that the letter was not proven to be connected in any way to Booth or any of his associates. Cox criticized Bingham’s explanation as to why the cipher was proper evidence.

According to Cox, Bingham’s logic was that: Booth was engaged in a conspiracy with some unknown persons, this cipher letter comes from an unknown person, and therefore this letter is from somebody connected with the conspiracy and constitutes admissible evidence. Cox referred to this as “chop logic” on the part of the prosecution and reiterated that the rule of law stated that the author of a declaration must be shown first when a letter is entered into evidence.

Cox then went on to explore the idea first mentioned by Thomas Ewing concerning how the cipher was undoubtedly a fabrication. The testimony stated that the letter was picked up out of the water in Morehead City yet the letter was not blurred from its contact with the water. Cox expressed his belief that it had been written and dropped into the water immediately before it was found by government agents for the very purpose of it being used as evidence. Cox then looked at the text, noting that it was dated April 15th, the day after Lincoln was shot. The text stated that “I was in Baltimore yesterday” and that “Pet,” assumed to be Booth based on the context of the letter, “had not yet got there.” Since, in context to the letter, “yesterday” would have been April 14th, the day of the assassination, it made no sense that “Pet” would be in Baltimore before his work of assassination had been done. Cox also laughed at the letter’s claim that on the night of April 14th, “We had a large meeting,” when it had been shown that most of the conspirators were fleeing for their lives.

John Bingham, continuing his objection to the motion, noted that the cipher letter and its corresponding testimony could not be struck out or erased by anybody through any motion. He conceded that Ewing could ask the court to disregard it but stated that the proper time for him to do so would be during his closing arguments. Bingham stated that asking the court to disregard this evidence now was akin to asking the court to try part of the case now and the rest of it later. Bingham also came to the defense of the letter and its contents, attempting to repudiate the words of Walter Cox. Bingham pointed out that the references to Sherman and Grant showed evidence of a conspiracy, one that was not known to anyone in America except the conspirators themselves, on April 15th. Cox then countered that they did not know what day it was written. Bingham stated that Cox, himself, had given credit to the date of April 15th during his criticisms of the letter. Cox still pointed out that it was not found until the 2nd of May, three weeks after the assassination, when knowledge of the conspiracy was well known to the public. He insisted that the evidence suggested the cipher was a forgery, “written by somebody who possessed himself of sufficient knowledge of the facts charged against the conspirators to enable him to fabricate a letter specious on its face and appearing to have some bearing on the conspiracy itself.”

In his own closing, John Bingham maintained that the contents of the letter proved it was genuine and that it had been in the possession of an unknown conspirator. Bingham believed that all other evidence in the case regarding the larger conspiracy (a large portion of which was later found to be perjury) corroborated the truthfulness of the cipher letter.

In the end, the commission sided with their advisor, Bingham, and overruled Thomas Ewing’s motion to strike the letter from the record. During the course of this excited debate over the cipher letter, “a lady fainted, and was carried out of the court-room.”

The “pet letter” was an obvious fake with no proven connection to Booth or his conspirators. Its admittance into evidence was yet another embarrassing error of judgment on the part of the government in its blind quest to connect the assassination of Lincoln to the Confederate government by any means necessary.

Quick(ish) Thoughts

- I’ve mentioned it before, but the government was not aware of Lewis Powell’s real name until about halfway through the conspiracy trial. Up until that point, he was a mystery man known only by the alias Lewis Paine. To learn more about Lewis Powell’s history and life up until his involvement with Booth, check out this post regarding his early life.

- I will give credit to the writers for doing their research on the trial exhibits. When Judge Advocate Holt is asking Eckert about the Confederate cipher cylinder recovered from Richmond, he notes that this is “exhibit number 59.” That is actually the correct exhibit number from the trial. Holt then switches to the handwritten Vigenère cipher table found in Booth’s room and calls it “Exhibit 7,” which, again, is the correct exhibit number for that piece of evidence.

- Jeremiah Dyer, a witness for Dr. Mudd, is portrayed as a pastor in Bryantown and speaks highly of Mudd’s reputation. In reality, Dyer was no pastor but Dr. Mudd’s brother-in-law. The doctor was married to Jeremiah’s sister, Sarah Frances Dyer.

- In much the same way that the series created a fictional Mary Simms, they also merged her two brothers into one character. While Mary’s brother Milo did testify at the trial (and at around 14 or so, was among the youngest to do so), he had never been shot by Dr. Mudd. Like his sister Mary, Milo had left the Mudd farm after emancipation came in 1864 and so he was not around when the assassin showed up. Dr. Mudd had shot the Simms’ older brother, Elzee Eglent, in June of 1863 when he felt the enslaved man was not working hard enough. Mudd also threatened to send Eglent to Richmond in order to help build defensive fortifications for the Confederacy. Eglent, along with a group of around 40 others, escaped from the farms belonging to Dr. Mudd, his father, and Jeremiah Dyer in August of 1863. Elzee Eglent did testify at the trial, just like the real Milo and Mary Simms, but there was no large reaction or an outburst from Mudd when he mentioned having been shot by the doctor.

- Despite Mary Simms appealing to the court to ask Louis Weichmann about the relationship between Dr. Mudd, Surratt, and Booth, in reality, Weichmann had testified about the connection between the men several days earlier. The real Mary Simms had no knowledge of any connection between Mudd and Booth.

- Edwin Stanton’s dramatic reading of the conspirators’ verdicts inside the packed trial room makes for compelling drama but is nothing like what occurred. There was no extra court session for the public during which the verdicts were read. After the commissioners finished their deliberations on June 30, their findings were sent over to the President for final approval. President Johnson officially approved the commission’s verdicts and sentences on July 5, and the condemned conspirators learned of their fates when the commander of the prisoner, General John Hartranft, brought them the news on July 6.

- For the sake of time, the conflict between Stanton and President Johnson, which resulted in Stanton’s ultimate removal from office, was sped up. For an overview of the full story, I recommend a quick read of the latter part of the Reconstruction section and the Impeachment section on Edwin Stanton’s Wikipedia page.

- The text stating that John Surratt held “rallies across America” about his connection with Booth is a bit misleading. John Surratt tried his hand at becoming a professional lecturer after his own trial ended in a hung jury. However, he only gave his talk about his connections with Booth three times. Once in New York City, once in Baltimore, and once in Rockville, Maryland. When he announced an upcoming talk in D.C., there was outrage, and he was reminded that he was never acquitted of the charges against him and that further lectures could provide evidence that the government could use if they decided to put him on trial again. This ended John Surratt’s short-lived career as a speaker.

Thus, we arrive at the end of Manhunt, the miniseries. Was this series an accurate adaptation of James L. Swanson’s nonfiction book documenting the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the search for his assassin? No, it wasn’t. From the historian’s viewpoint, this series was a turducken of factual tidbits stuffed inside dramatic license, all stuffed inside imagination.

Looking back on my own reviews, it’s clear how my opinions became more jaded as the series went on. In the beginning, I so badly wanted to give the writers the benefit of the doubt as I understood that I was the worst critic for this series because of my knowledge of the actual events. As the series went on and continued to deviate so extremely from the actual history, the excitement and hope I once felt for the series waned quickly. This is why it has taken me 8 months since the release of the final episode to finally review it.

Even as I criticized each episode, I strove in each of my reviews to point out aspects of the series that I liked, such as my enjoyment of many of the supporting actors in the series, particularly the portrayals of David Herold, Andrew Johnson, Mary Simms, and Thomas Eckert. At times, the series pleasantly surprised me by including a fact I did not expect them to bring up. This is to say that despite my groaning about some things, there is still much to like about the series. When I turn off my brain and watch the series as the piece of historical fiction that it is, I enjoy the compelling drama.

In the end, I know my opinions of this series would likely have been kinder had it been called anything other than Manhunt. If the series were called The War Secretary or something like that, there would no longer be any expectation in my mind that the series would stay true to a non-fiction book about the Lincoln assassination. The writers of this series were clearly stuck between a rock and a hard place. They wanted to write a series about Stanton, Johnson, and the fight for the future of the country during Reconstruction, which is a noble and worthwhile idea. The best parts of this series are the times when it is allowed to explore this aspect of history. Unfortunately, the attempt to merge this series idea with another about the hunt for John Wilkes Booth resulted in a mismatched marriage where neither history got the attention that it deserved.

Dave,

Greetings from WV. You are providing an important service. One note re Mudd: Before discovering the “Sam” letter when Voltaire Randall and Eaton Horner arrested Arnold at Fortress Monroe he told them that Booth carried a letter of introduction from someone (didn’t know who) in the Canadian SS to Mudd. This can only mean that the authorities could link Mudd and Booth well before the Bryantown interrogations. The claim that we would never had heard of Mudd had Booth not broken his leg is bogus. Have a great holiday and keep up the good work.

Ed Steers

It’s wonderful to hear from you, Ed. Thank you for your kind words. I’m merely reiterating the wonderful work done by the true experts in our field like you and Michael Kauffman.

Thank you for the reminder about Eaton Horner’s testimony regarding how Samuel Arnold made mention of Dr. Mudd during his initial interrogation. You are quite right that Dr. Mudd’s name was known to the authorities as early as April 18th, the same day the first group of soldiers visited the Mudd farm.

Finally, it is complete! I enjoyed seeing your takes and completely agree with them. A bit of a disappointing series, but fun, nonetheless.

Had a good read of this with a friend. We love your work and often sit at lunch or in the library reading this blog. Thanks, Dave! Happy Holidays!

I’m glad you enjoyed these long write ups of mine. Thanks for your patience with them. It’s rewarding to hear such positive feedback. Happy Holidays to you and yours, as well.