I am conducting an ongoing review of the seven-part AppleTV+ miniseries Manhunt, named after the Lincoln assassination book by James L. Swanson. This is my historical review for the fifth episode of the series “A Man of Destiny.” This analysis of some of the fact vs. fiction in this episode contains spoilers. To read my reviews of other episodes, please visit the Manhunt Reviews page.

Episode 5: A Man of Destiny

This episode opens with John Wilkes Booth and David Herold realizing that their night of rowing on the Potomac has not brought them to Virginia but that they have accidentally landed back on the Maryland shore. After changing into Confederate uniforms claimed from bodies on the riverbank, the pair head off into the water once again, hoping to make it to Virginia. Edwin Stanton, with his fictional map of the Confederate secret line in hand, comes across the members of the 16th NY Cavalry in the field at an undisclosed location. We meet the “man of destiny” pictured above, Sgt. Boston Corbett, whose salvation from past sins and tragedy is shown in a flashback. With the 16th in tow, Stanton and his group ride on, coming across a band of wounded Confederate soldiers. The war is over for them, and all they want is to get their oaths of allegiance and be allowed to go home. At that moment, a messenger arrives and informs Stanton that President Johnson is rolling back the land grant program to recently freed Black Americans. Stanton heads back to Washington, leaving the 16th to carry on with their search. In a flashback scene, we see Stanton and a delegation of Black leaders three months before the assassination discussing the land grant program with General Sherman in Georgia. After the appeal, Sherman agrees to the proposition. Back in D.C., Stanton confronts Johnson about abandoning the Freedmen. But the President has already been convinced by Southern statesmen to end the land grants. Back at the War Department, Thomas Eckert advises Stanton not to quit over this loss but to stay on and protect the rest of Lincoln’s reconstruction plans.

Back in Maryland, Mary Simms reads the announcement that all land grants are suspended and realizes her dream of starting a school on her new property is not to be. She returns to Dr. Mudd, who takes her back as his servant, but not before beating her offscreen as a lesson for “running off.” After landing in Virginia, Booth and Herold walk through the day before coming across an empty cabin. They bed down for the night but are awakened the next morning by the cabin’s owners, William and his teenage son Charley Lucas. At gunpoint, Booth and Herold force the Lucases to hide them in their wagon and transport them to the Rappahannock River ferry. The fugitives wait at the ferry crossing with the same band of wounded Confederates Stanton and the 16th NY stumbled across earlier. One of the wounded Confederates engages Booth in conversation after noticing his tattooed initials. Booth demurs at first, giving an alias for himself and Herold. However, after the wounded Confederate starts to question aspects of the pair’s service record, Booth drops the charade and announces his identity to the whole gathered group. He is surprised to see that the men do not see him as a hero but a coward who shot an unarmed man.

When the ferry arrives to take them across the river, only one Confederate talks with the men. He is Willie Jett, and he explains that he is going to marry a wealthy woman in Bowling Green, so he’s not afraid to talk to the assassins like the rest of the men. Jett advises the pair to go to the farm of Mr. Garrett on the other side of the river for he might give them a place to rest. Booth thanks Jett. When the Black ferry operator, Jim Thornton, gives Booth a look, the assassin yells that folks like him “don’t get rewards.” Back in Washington, Eddie Stanton returns and tells his father that the 16th NY is still looking for Booth around the Potomac River. Eddie then recalls that Dr. Mudd lives near the “secret line” stop of Bryantown. Sec. Stanton rides down to Dr. Mudd’s farm in Charles County and interrogates the doctor. The beleaguered Mary Simms silently directs Stanton to search the upstairs room where Booth had been treated. The Secretary finds the boot that Mary had put under the bed after the assassin departed. Inside the boot, Stanton finds the damning initials, “J.W.B.”

Back downstairs, Stanton accuses Mudd of having known Booth previously. Mudd denies he knew the men who came to his house or what they had done. Here, Mary Simms finally finds her voice and tells Stanton that Mudd was lying and that he knew both Booth and John Surratt. Under Mudd’s protestations, he is arrested and taken away. Stanton, admiring Mary’s bravery and knowing she was now out of a job, offers her a place in a Freedmen’s camp in Arlington. The Secretary also realizes that a broken-legged Booth would blend in well with a group of wounded Confederates making their way South. Stanton once again uses his teleporter to make his way down to the ferry landing on the Rappahannock accompanied by Eddie, Eckert, and the 16th NY Cavalry. Ferryman Jim Thornton tells the men that Booth crossed the river earlier that day and that he had conversed with a regular named Willie Jett, who stays at the Star Hotel in Bowling Green. Meanwhile, we cut to Booth and Herold at the Garrett farmhouse. Booth has a fever and is being given a bath by Julia Garrett, who calls him a hero to the cause. Stanton and the cavalry appear in Bowling Green, and Willie Jett is found at the Star Hotel. The man who claimed he wasn’t afraid of the law immediately folds and tells Stanton the fugitives were likely to be found at the Garrett farm. Excited to capture the men before daybreak, Stanton rushes to his horse when his ever-worsening asthma causes him to collapse. Unable to go on himself, Stanton sends the 16th NY on with Boston Corbett leading the charge back up the road to the Garrett farm.

Before I discuss some of my criticisms and my analysis of fact vs. fiction in this episode, I want to highlight things that I liked about it.

- “I almost enlisted once.”

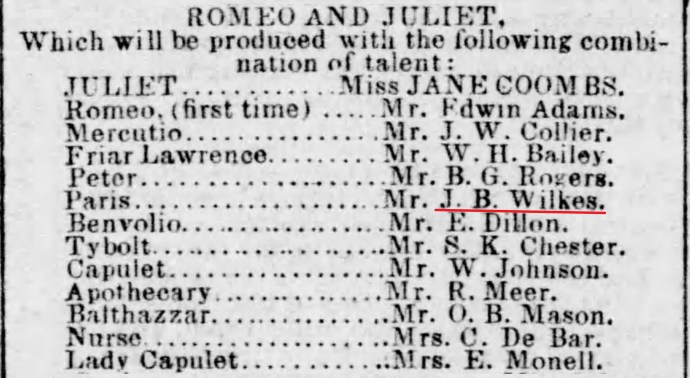

At the very beginning of the episode, when the pair land their rowboat in what proves to be Maryland, Booth observes the dead Confederate soldiers on the shoreline and relates how he “almost enlisted once.” He mentions the “low wages” and “terrible food” that “those poor bastards” had to endure. He also complains about the uniform and how he prefers to choose his own look. These are largely throwaway lines, as the real focus is on Davy, who is actively consulting the compass and apparently determining they are in Maryland. However, there is a grain of truth in Booth’s recounting of a soldier’s life. In reality, John Wilkes Booth did enlist once, but not during the Civil War. Instead, Booth spent a little bit over two weeks as a part of a local militia, the Richmond Grays, at the end of 1859. This was during the time when Booth was learning his craft as a lowly stock actor attached to a theater troupe in Virginia. He performed under the name “J. B. Wilkes” and played supporting roles to the visiting stars.

Booth was in Virginia when abolitionist John Brown enacted his famous raid on Harper’s Ferry. The slave uprising Brown hoped to inspire did not occur. Brown was captured alongside many of his fellow raiders and tried for treason against the state of Virginia. Brown was found guilty, and his sentencing took place on November 2. He was sentenced to death, with his execution being scheduled for December 2. During the interim between Brown’s sentencing and pending execution, rumors began to build that efforts were being made to free Brown from his prison cell in Charlestown, VA (now Charles Town, WV). As a result of these rumors, Virginia Governor Henry Wise called up state militia groups to report to Charlestown in order to guard Brown and prevent any plots to free him. During Booth’s time in Richmond, he had befriended several men who were part of the local militia group known as the Richmond Grays. Inspired by the call for guards, Booth left the theater troupe and joined up with the Grays as they loaded up onto a train bound for Charlestown. For two weeks, Booth played the role of a soldier. He was assigned duty as a sergeant with the regimental quartermaster’s department.

For these two weeks, Booth acted as a clerk and occasional guard outside of Brown’s prison. This culminated with Booth seeing Brown in his cell on the eve of the abolitionist’s execution. Booth stood by and watched as Brown was hanged on December 2, becoming slightly queasy from the scene. A few days later, Booth was back in Richmond and managed to reacquire his position with the theater troupe due to the intervention of his fellow Grays.

While brief, Booth’s “gone a soldiering” period made an impact on the future assassin. When he was younger, Booth had written jealously of the noble fighting of soldiers in distant countries. His time with the Richmond Grays allowed Booth to see the reality of a soldier’s life. He experienced the drudgery, boredom, and lack of autonomy of being a lowly private in a military unit. I believe his experience of having to take orders and complete menial duties with the Grays is what caused Booth to avoid enlisting when the Civil War began. Booth’s sense of self-importance would not allow him to follow the orders of others. He wanted the glory of being a soldier, but he didn’t want to have to work for it. Instead, he wanted to be the one in charge. This is alluded to in the miniseries when, on the river bank, Anthony Boyle’s Booth wonders about the position he will be given by Confederate officials when they get to Richmond. He, of course, concludes that he will be made a general.

While this series never goes into Booth’s time as a soldier with the Richmond Grays, this brief scene does a good job of alluding to Booth’s experience as a quasi-enlisted man. It shows Booth’s distaste for following orders and why he could never bring himself to actually fight for the cause that he claimed to hold dear.

- Boston Corbett

My list of favorite character performances increased with this episode. While I’m still a fan of Glenn Morshower’s depiction of the duplicitous Andrew Johnson and Damian O’Hare’s reliable Thomas Eckert, William Mark McCullough’s portrayal of Boston Corbett grabs your attention from the moment he turns up on screen. With a few lines from colonels Baker and Conger, we are given a modified backstory for the future avenger of Lincoln. Then, through monologue and a snowy flashback, more of this unique gentleman’s history is shown.

While William Mark McCullough is considerably larger than the actual Corbett, who was left even thinner after experiencing the worst of Andersonville prison, the actor expertly brings his own sense of divine madness to the character. After watching this episode for the first time, I discussed it with my good friend, Steven Miller, THE expert on Boston Corbett and the 16th NY. We both noted how impressed we were at McCullough’s performance. Later in this review, I’ve included Steve’s assessment of the facts in the Corbett scenes. I’m sure you won’t be surprised to learn that the writers took some creative liberties here, but this is one of the few times where I felt that the choices they made were actually done well.

- This episode is about the manhunt

Out of all of the episodes, this one is my favorite because of one simple idea: this episode, more than any other, is actually about the escape of Booth and the manhunt to find him. We’re not wasting time with the fictional George Sanders intrigue anymore, and the secondary plotlines don’t take up as much time in this episode. For the first time, Booth’s escape and the efforts to find him are the main focus. With that being said, this episode is also the most frustrating one so far because very little of Booth’s escape during this period is accurate. Instead, it is significantly shortened, incorrectly represented, and the search by the 16th New York is dramatically altered. This is why this review, out of all of them, has taken me the longest to write. Still, this episode comes the closest to what I expected from a series called Manhunt.

Let’s dig now into the fact vs. fiction of this episode and learn about the true history surrounding these fictional scenes.

1. Crossing the Potomac

As much as I enjoy part of the initial scene where Booth reflects on not joining the Confederate army, several glaring errors occur here. The pair is supposed to be landing at Nanjemoy Creek in Charles County, Maryland. After failing to cross over into Virginia, the actual Booth and Herold stayed in this area called Indiantown Farm for about 48 hours. Local lore states that they remained hidden in an old slave cabin that still exists on the property. Then, on the night of April 22, they attempted to cross the river again under the cover of darkness, and this time, they were successful at making it to Virginia. The series shortens this part considerably. After Davy determines they have landed in Maryland by mistake, they immediately prepare to take the river again during the daylight hours.

The real fugitives would never have risked setting off on the Potomac during the daytime, where they would have been easily spotted by the different ships patrolling the river and the soldiers on either shore who were looking for them. But, for the sake of moving the story along and for the ease of filming during the day, I can understand why the miniseries chose to truncate this. The very wild curveball the series throws during this scene, however, is the numerous dead Confederate soldiers strewn near the riverbank in Maryland. There is no explanation for this camp of dead Confederates. It seems their existence in the story is merely to give Booth and Herold a convenient way to change their clothing.

Both Booth and Herold put on the dead Confederates’ uniforms and wear them for the rest of the escape. In reality, this never happened. At the Garrett farm, Booth did attempt to swap his suit with one of the Garrett son’s old Confederate uniforms, but Will Garrett declined this offer. Booth and Herold wore their civilian clothes throughout their escape, and Davy was photographed wearing the same clothing he was arrested in.

I can only assume that the writers decided to have Booth and Herold change their clothing in this scene as a setup for the later “reveal” at the Rappahannock Ferry landing, where one of the wounded Confederates calls the fugitives out for posing as soldiers. But, of course, that scene is also fictitious. We’ll get to that later.

2. Boston Corbett’s backstory

Here’s some of what Steve Miller, the expert on Boston Corbett and the 16th New York, had to say about the accuracy of the character of Boston Corbett in this episode:

“First off, the writers did a masterful job of introducing him as a new character. In a tightly written couple of scenes they managed to give his backstory succinctly and set him up as major impediment to Booth’s plans.

I have a couple of quibbles with their version of Corbett’s story. There is NO, I repeat ZERO evidence that he was an alcoholic. Yes, he was a widower; his “good Christian wife”, Susan Rebecca Corbett (not “Emily” like in the series) died of “disease of the liver” not from a troubled pregnancy. (These ideas were not created by the Manhunt writers, however. Many books have made both claims, but there is no substantiation for them. They just keep getting repeated.)

Corbett was shown sitting alone in the rain, engaged in a conversation with the Lord. He was described by a friend as being “the only man in our regiment who openly professed his religion.” This was not a big deal in the 16th NY Cavalry, but he had frequently been physically assaulted and suffered continual tormenting in the infantry unit he had belonged to before.

I would like to have had the writers tone down the “crazy eyes” portryal of Corbett a little. Many shows which bother to portray self-identified Christians at all, overplay them as totally consumed near jihadist zealots or hypocrites. Corbett was evangelical, of course, but he did not try to impose his beliefs on others. The tenants of his faith were to tell the truth, perform good works, and bear witness to God’s grace. As he usually did, he even prayed for Booth’s soul as he fired to keep Booth from harming others. That would have been a nice bit of dialog to add.

I’m not sure that Corbett personally led the charge back to Garrett’s farm. (BTW, the farm was roughly fifteen miles from Bowling Green. That’s where Stanton was being treated in the miniseries.) Corbett was very active during the last phase of the search/capture, but he was fourth in command of the 29-man posse. Doherty (who was left out of Manhunt altogether), Byron Baker and detective Conger were in command.”

I will add more of Steve’s thoughts when we get to the next episode. Even with these historical quibbles, we both agreed that Cobett was well portrayed.

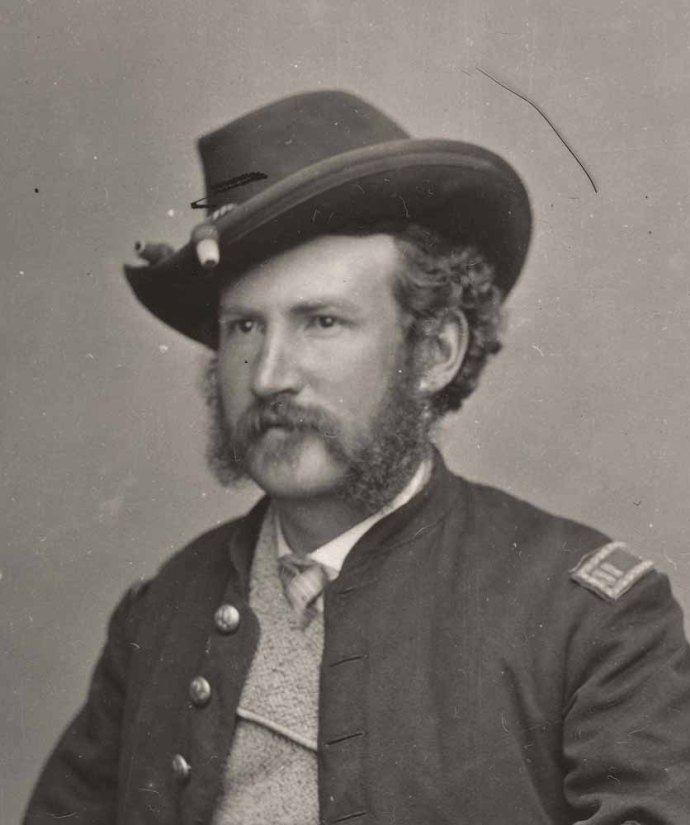

3. The Missing Leader: Lt. Doherty

As Steve mentions at the end of his comments above, there is a noticeable absence within the men of the 16th New York Cavalry in this miniseries. For unknown reasons, this series decided to eliminate the leader of the Lincoln Avengers: Lt. Edward Doherty. While arguments over the payouts for reward money will forever impede our ability to know who was truly “in charge” of the group that hunted down and killed John Wilkes Booth, there’s no arguing that the leader of the soldiers themselves was Lt. Doherty. When the rewards were eventually paid out, Doherty received $5,250 – the largest share of any of the detectives and troopers. He played an important role in tracking down and capturing Booth but is nowhere to be seen in the series. With so many characters, it would be understandable for some to be cut out, but Doherty seems like an odd omission, given his importance. What makes it even more confusing is that they have a Doherty look-alike with the 16th New York.

Looking at this screenshot, you would think you were looking at Lt. Doherty and Luther Byron Baker (cousin to Patton Oswalt’s Lafayette Baker). However, while the actor on the left, Judd Lormand, is wearing Doherty’s signature mutton chops, he does not play Lt. Doherty but is credited as Everton Conger. Like Luther Byron Baker, Everton Conger was assigned to the 16th New York in a detective capacity. He and Baker also took key roles in the manhunt for Booth. Why the production chose to put Doherty’s facial hair on the actor playing Conger is unclear. The real Conger was bearded, much like Baker. He’s a picture of the real Conger and Baker that they posed for after successfully tracking down Booth.

It’s unfortunate that the production decided to omit Lt. Doherty from his rightful place, but even more baffling that they decided to make Everton Conger look just like the man they erased from the story.

4. Booth and Herold’s April 23rd is Much Altered

In the series, the uniformed Booth and Herold land in Virginia on their second attempt and immediately begin walking. We are led to believe that they walk through the day until they stumble across an empty cabin at night, where they make themselves at home. It is not until the morning that the cabin’s owners, a Black father and son by the name of William and Charley Lucas, return. While it is true that Booth and Herold did sleep the night of April 23 in a cabin belonging to the Lucases, the series has removed quite a bit of activity between their arrival in Virginia and their stay at the Lucas cabin.

Here’s a brief synopsis of what occurred for the real Booth and Herold on April 23, as told through screenshots from my digital map of Booth’s escape:

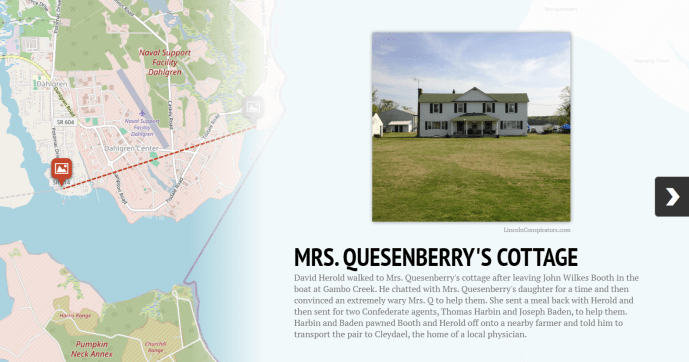

As can hopefully be seen from these screenshots, upon their arrival in Virginia, Booth and Herold received far less than a warm welcome. April 23rd is a key part of Booth’s escape. In Maryland, Booth was fairly well taken care of. Dr. Mudd set his leg and let him rest at his home. While Samuel Cox forbade him from staying at Rich Hill, he did arrange for Thomas Jones to care for the men in the pine thicket and eventually set them across the river. As the miniseries accurately shows, Booth truly thought he would be greeted as a hero in the South. The hardship of living in the pine thicket for over four days was made tolerable by his belief that he would be welcomed with open arms by the people of Virginia. Yet, the second he arrived on the Virginia shore, no one wanted anything to do with him. Even though Mrs. Quesenberry had helped with the Confederate mail line, she was nervous to have the fugitives near her house. She pawned the men off on Thomas Harbin and Joseph Baden. These fellow Confederate mail agents believed the fugitives to be too hot for them and quickly passed them to farmer William Bryant. He took the men as ordered to the home of Dr. Stuart. The wealthy doctor and Southern planter gave the men a meal but refused to render medical aid to Booth and would not lodge them for even a night. In the end, the racist Booth is forced to sleep in the home of a Black family. This series of events was a massive blow to Booth’s ego and severely deflated him. Rather than being treated as the savior of the South, these Virginians wanted nothing to do with him. It’s too bad the series couldn’t have shown the process of humbling Booth and how he came to realize how alone he truly was.

5. At the Rappahannock River

The series did not completely neglect knocking Booth down a peg or two. Rather than showing his treatment by several Virginian civilians, the series instead decided to create a fictional scene between the assassins and several wounded Confederates at the Rappahannock River. Here, we see Booth and Herold waiting on the ferry in Port Conway with the same group of homebound Confederates Sec. Stanton ran into a few scenes earlier. The lead unnamed Confederate bearing an eyepatch, notices Booth’s initials of JWB and makes the connection to Booth. Instead of revealing his identity, Booth gives his name as John Wilson Boyd and introduces Davy as his cousin Larry. Eyepatch asks Mr. Boyd where he got his “glory,” i.e., his noticeably broken leg. Booth responds with, “Bull Run” before asking Eyepatch where he earned the medal pinned to his chest. Eyepatch replies, “Bull Run,” before saying that Booth and Herold’s uniform don’t match “what we wore there.” Booth understandably replies that he has changed his clothes since the battle. But Eyepatch is unconvinced and calls the men cowards for falsely posing as veterans. This pushes Booth over the edge, and he removes his 1st Texas Infantry cap, runs his fingers through his hair, and vainly identifies himself as having been at Ford’s Theatre on April 14th. At first, Davy tries to pass this admission off as a joke, but Booth doubles down, announcing himself as the assassin of Lincoln. Booth tells of his glorious act and fully expects the soldiers to fawn over being in his presence.

The news, however, goes over like a lead balloon. Eyepatch calls his act despicable and spits at the ground before Booth’s feet. The other Confederates mostly nod in agreement with Eyepatch or are completely nonplussed by the whole thing, more focused on their injuries and desire to get home. Booth is only saved from more humbling by the ferry, which arrives from Port Royal. Eyepatch asks the ferry operator, Jim Thornton, how far it is from the ferry landing in Port Royal to the Union office. Thornton replies the Union office is just directly across the road.

As the men line up and prepare to get on the ferry, only one soldier is willing to talk to them. Though not identified at the time, we come to learn that this is Willie Jett. He asks Booth and Herold where they are going and Booth replies Richmond. Herold asks if Jett can help them. Jett recommends the men stop at the farm owned by a man named Garrett, who owns horses they might be able to use. He says that Garrett’s farm is the “first farm before town center” and that he might host them for a price. When Booth asks what is wrong with the rest of the soldiers, Jett explains that the last thing any of them want is to be arrested for helping the assassins of Lincoln. Booth then asks why Jett is so willing, and Jett replies that he’s going to marry the wealthiest girl around, so he doesn’t care about the law. Still, aside from suggesting the Garrett farm, Willie Jett does not provide any other assistance to the fugitives. The scene ends with the men about to board the ferry to Port Royal.

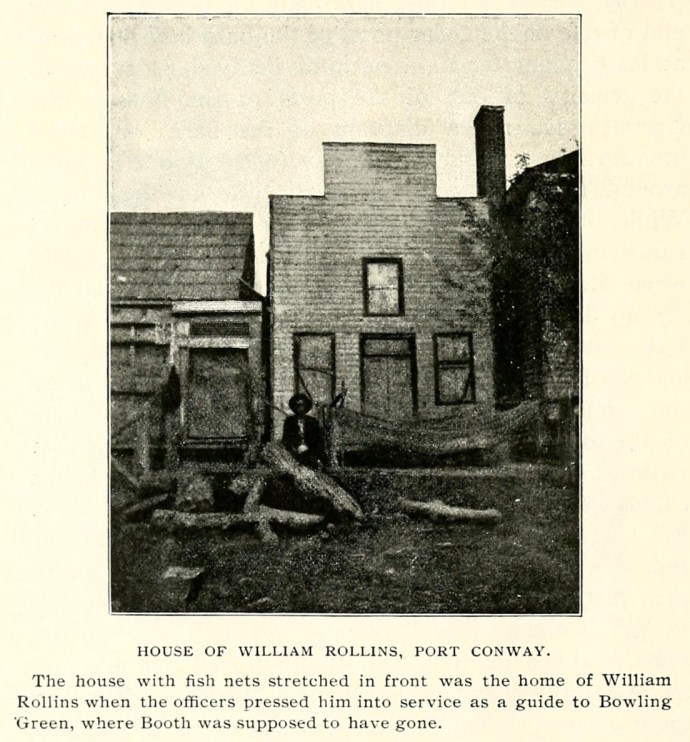

Let’s break down what we have just seen in this fictional scene and compare it to Booth and Herold’s actual time near the Rappahannock. Booth and Herold were the only two people waiting on the ferry after they arrived at Port Conway via Charley Lucas’ wagon. It wasn’t the busiest of crossings, and it appears that Booth and Herold were unaware that they were supposed to hail the ferry boat in order to get it to come across the river. Impatient to continue south, they found a local resident named William Rollins, who was preparing his boat and nets for some fishing in the river.

They asked Rollins if he knew of anyone in Port Royal who might furnish them with transportation to Orange Court House. Rollins said he did not know of anyone, so the pair asked if Rollins himself might guide them. As the series shows, Booth was claiming to be a wounded Confederate soldier at this time, though he was still wearing his civilian clothes, so Rollins had no reason to suspect the men. Orange, Virginia, was the home to a railroad hub that Booth and Herold intended to use in order to get further South. However, even using modern roads, Orange is about 60 miles from Port Royal, and William Rollins had never been there. His best offer was to take the strangers to Bowling Green, about fifteen miles to the southwest. Booth and Herold agreed to this and asked if Rollins would take them across in his boat. Rollins said he would, but not at this moment, as the tide was nearly ready, and he needed to put his nets in the river in order to catch some shad. Booth and Herold would have to wait.

While Rollins took his boat out into the river to set up his nets, three Confederate soldiers rode into Port Conway. They were Willie Jett, Absalom Bainbridge, and Mortimer Ruggles. Like the fictional Confederates in the miniseries, these men were making their way home now that the war was effectively over. The three men hailed the ferry boat at Port Royal and waited as the operator, Jim Thornton, started the slow process of preparing the ferry and pushing it across the water towards them. During this time, Davy Herold started up a conversation with the Confederates, trying to learn more about them and where they were going. According to Jett, Davy claimed his name was David E. Boyd and that his companion was his brother, James William Boyd, not John Wilson Boyd and cousin Larry, as the miniseries states. Davy said they were both Confederate veterans from Maryland and that they desired protection and help from these men, their fellow soldiers. Booth was fairly quiet during this period and let Davy talk. Remember that Booth had been quite humbled by this point due to the less-than-helpful treatment he had received from others in Virginia up to this point. Eventually, it was Herold who confessed to the Confederates their true identities as “the assassinators of the President.” The three Confederates agreed to provide some assistance to the fugitives.

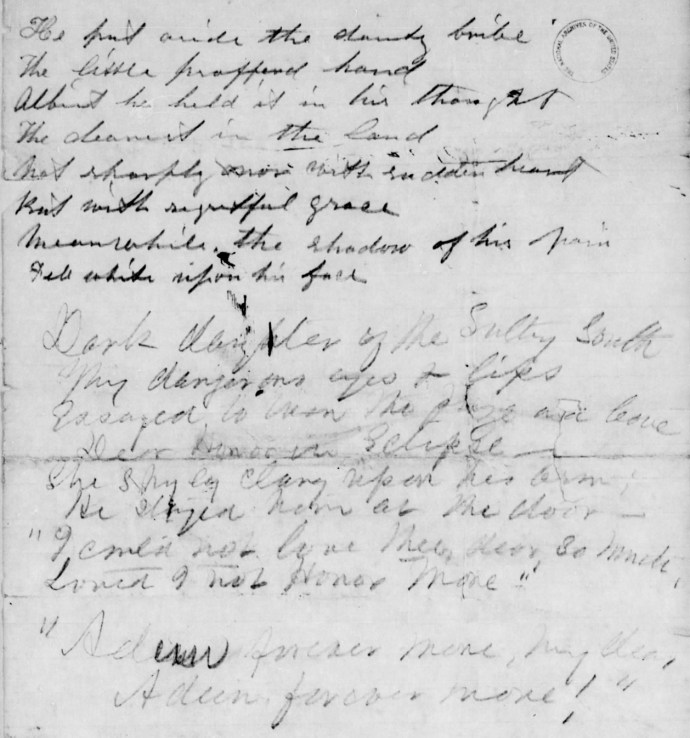

Not long after, William Rollins returned from setting up his nets. He asked Booth and Herold if they still wanted a ride across the river and escort to Bowling Green. Davy replied that they had met up with some friends (Jett, Ruggles, and Bainbridge) and that they no longer needed Rollins’ services. However, before the ferry arrived, Davy did ask Rollins if he could borrow some ink. Rollins allowed Davy and Jett into his home, where he saw Davy write out a document of some kind. According to Jett, Davy was copying down a fake parole document that the pair could use in case they ran into trouble. It is also likely that it was during this time that both Booth and Herold composed the following document. It is two poems, the top written by Booth and the bottom written by Herold. My best attempt at a transcription of the poems follows the image:

He put aside the dainty bribe

The little proffered hand

Albeit he held it in his thought

The dearest in the land

Not sharply nor with sudden heart

But with regretful grace

Meanwhile the shadow of his pain

Fell white upon his face.Dark daughter of the Sultry South

Thy dangerous eyes & lips

Essayed to win the prize and leave

Dear Honor in Eclipse

She shyly clung upon his arm

He stayed him at the door

“I could not love thee, dear, so much,

Loved I not Honor more”

“Adieu forever more, my dear,

Adieu forever more!”

In truth, we’re not exactly sure when and where Booth and Herold composed this poem during their escape, but it’s possible it occurred while waiting at the Rappahannock as an autograph of sorts for Willie Jett.

Eventually, Jim Thornton arrived with the ferry on the Port Conway side of the river. In those days, the ferry was essentially a flat-bottom barge. Thornton pushed the barge across the river using a long pole, not unlike Charon, the Greek mythological figure who was said to transport the souls of the dead over the River Styx in such a manner. This type of ferry continued to be used at this crossing until 1934 when a bridge finally connected the two port towns. Here’s a picture of the Port Conway/Port Royal ferry circa 1930, which was not all that different from when Booth and Herold crossed sixty years earlier.

6. In Port Royal

Rather than just leaving Booth and Herold with some advice, as the miniseries’ Willie Jett does, the real Jett and his companions actively looked to see if they could find someone in Port Royal to take in the fugitives for a day or two. This included knocking on the door of Sarah Jane Peyton, who originally agreed to take in a wounded Confederate soldier, only to change her mind once she saw Booth’s condition.

After trying a couple of other houses in town with no success, the decision was made to ride about two and a half miles out of town to the farm of Richard Garrett, whom Jett knew by reputation. Mr. Garrett had a large farm and two sons who had recently returned from Confederate service. The hope was that he would be happy to take in a stranger or two for a few nights. The men then rode out of Port Royal to the Garrett farm, with Booth and Herold sharing a horse with Ruggles and Bainbridge.

All of the events that took place in Port Royal are cut out of this episode. The next time the miniseries shows Booth and Herold after the ferry landing scene, they are walking on a road in the woods near sunset. Booth is using his crutch and trying his best, but he is clearly in pain. After cursing for a bit, he tells Davy that he can’t make it to Richmond tonight. The pair veer off their path, and a convenient road sign states that it was 50 miles to Richmond. How Booth and Herold ever thought they were going to walk to Richmond is beyond me. Luckily for them, the sign says their new route is only 2 miles from Bowling Green.

This road sign indicates that the pair have walked right through Port Royal and many miles past the Garrett farm. Here’s a map to demonstrate what I’m talking about.

I have circled the towns of Port Conway on the north side of the Rappahannock River, Port Royal on the south side, and Bowling Green, which is about 13 miles away to the southwest. The green pin marks the location of the Garrett Farm. The red pin marks the approximate area where the fictional roadsign in the series would be, 2 miles away from Bowling Green. As we can see, if Booth really did find himself two miles away from Bowling Green, then he had drastically overshot his target.

These scenes just show how poorly the series understood the geography of Booth’s actual escape. This is further shown by the fictional Willie Jett’s description of the Garrett farm being the “first farm before town center.” This doesn’t make any sense. The Garrett farm was located after the Port Royal town center from the perspective of a traveler crossing the river from Port Conway. Based on the road sign and the fact that the next scene shows Booth and Herold at the Garret farmhouse, makes it clear that the writers confused Port Royal with Bowling Green. Rather than putting the Garretts on the outskirts of Port Royal, the farm has transported itself to just outside Bowling Green.

Poor Port Royal, which actually has a nice Museum of American History featuring artifacts connected to Booth’s escape, is completely left out of the narrative of this series.

7. The Garrett Farm

We only have a brief scene of Booth and Herold at the Garrett farm in this episode. It consists of Booth being bathed by Julia Garrett, one of the Garrett daughters, who calls him a hero. As it probably goes without saying, this scene is entirely fictional (and creepy). None of the Garretts knew Booth’s identity until after he had been shot by Boston Corbett. In addition, while Julia Frances Garrett was a member of the Garrett family, she died in 1851 at the age of 10 months.

I’ll have more to say about Booth’s final hours at the Garrett farm in the next episode review (whenever I get around to that), but in a nutshell, this episode left out the fact that Booth was dropped off at the Garrett farm on April 24 and Davy did not initially stay with him. Davy rode on with Jett, Ruggles, and Bainbridge towards Bowling Green. While Booth spent his first night in the Garrett house, sleeping in a bed and cared for as a wounded Confederate soldier, Davy spent the night outside of Bowling Green at a different home with Absalom Bainbridge. The next day, Davy returned to the Garrett farm with Bainbridge and Ruggles and asked to join Booth, which was granted. All in all, Booth spent about 40 hours at the Garrett farm before his death, while Davy was only there for about 15 hours.

Quick(ish) Thoughts:

- While a compass is a helpful tool for telling you what direction to travel, it does not tell you where you are. Davy using the compass to determine they are still in Maryland rather than Virginia at the beginning of the episode doesn’t make logical sense.

- Booth is still on about going to Richmond despite everyone and their mother having told him the Confederate capital has fallen and is occupied by the Union. Again, the real Booth knew Richmond was a no-go, and he was heading for the Deep South instead.

- Andrew Johnson’s meeting with Southern representatives is interrupted by protestors calling him illegitimate. The President states the protesters have kept him up at night. This never happened. While Johnson was certainly criticized in places like the press, the White House was not the site of civil protests of this sort. That is a more modern practice.

- When Stanton and his son come across the 16th New York Cavalry, he orders them to search all the places on the fictional “secret line” established in the prior episode. Eddie Stanton, Jr. is seen passing out small pieces of paper to some of the troopers, apparently of the addresses on the “secret line.”

The diminutive size of these notes, however, could easily be confused with period carte de visite photographs, which would actually be correct. In order to help identify Booth, the War Department cranked out hundreds of copies of Booth’s photograph and gave them to the many military units searching for Booth, including the 16th NY. After Booth was shot and carried to the porch of the Garrett house, Boston Corbett took out the copy of Booth’s photograph that was given to him during the manhunt and had the Garrett family conclusively identify the wounded man on the porch as the same man from the image. I originally thought the miniseries had gotten this detail right and that Eddie was passing out copies of Booth’s photo before I realized these small papers were supposed to be related to the “secret line.” So close.

This image of the assassin was duplicated and given out to numerous soldiers on the manhunt for Booth.

- As mentioned above, the geography of this episode is very confusing. At the end of episode 4, Stanton, Eddie, and the random Union soldier are riding down the road toward Southern Maryland while perplexingly saying, “To Virginia.” Today, the Route 301 bridge connects Charles County, Maryland, to King George County, Virginia, but this bridge did not exist in 1865. The only way to get to Virginia from the route taken by Booth and Stanton at the end of episode 4 was to cross the Potomac River on your own using a rowboat or ship. We never see Stanton actually cross a single bridge or catch a ship across any rivers during this episode. As a result, it is unclear where Stanton meets up with the 16th NY and orders them to follow the “secret line.” Since some of the secret line sites include Bryantown and Samuel Cox’s Rich Hill, one would think the troopers are waiting somewhere in Maryland. In reality, the 16th NY was stationed in the Lincoln Barracks in D.C., quite close to Secretary of State William Seward’s home behind the White House, when they were ordered to a nearby wharf in order to be steamed downriver to Belle Plain, Virginia. It is equally uncertain where Stanton and the 16th NY come across the group of wounded Confederate soldiers bound for “Port Conway and Bowling Green,” both of which are in Virginia. So perhaps the 16th was meant to have been in Virginia the whole time, and Stanton just used his teleporting abilities to hop over the Potomac? It’s really a nightmare, geographically speaking.

- I made an appearance on the Civil War Breakfast Club podcast not too long ago for a talk about the miniseries as a whole. During our almost 2 hour discussion of the series, Darin and Mary educated me about General Sherman and Special Order 15, which gave land grants to the formerly enslaved. The series portrays Mary Simms receiving a land grant in Charles County, Maryland. In this episode, Johnson rescinds the land grants, and Mary Simms is forced to give up her new home. She then returns to Dr. Mudd, who beats her for running off. Aside from the strange nature of Mary Simms returning to Dr. Mudd instead of trying to find employment elsewhere, Darin and Mary explained to me that the “40 acres and a mule” program described in the series did not take place in Maryland. Special Orders 15 only related to the formerly enslaved men and women who traveled with General Sherman’s army during his march to the sea. The only land granted by these orders were coastal properties in Georgia and the Carolinas. While there is a flashback scene showing Stanton trying to get Gen. Sherman to agree with the program, which is closer to being accurate, in reality, Special Order 15 would not have affected anyone in Maryland.

- The series shows both William and Charley Lucas transporting Booth and Herold in a wagon down to the Rappahannock River. In reality, only Charley went with the fugitives, and this was to ensure that the men would not attempt to steal the horses and wagon. While I appreciate William and Charley commenting on the fates of traitors as they drive Booth south, there is no evidence that any of the Lucases knew who Booth and Herold were or what they had done.

- At the ferry landing, Booth says he was wounded at Bull Run. At first, I assumed that Booth calling it Bull Run would be the dead giveaway to Eyepatch that he was an imposter. Bull Run was not the name the Confederates used for either of the two battles that occurred near the Prince William County, Virginia, city of Manassas. Since these two battles, the first in 1861 and the second in 1862, took place near the Confederate city of Manassas, the Confederacy referred to these as the Battle of First Manassas or the Battle of Second Manassas. The Union referred to these battles as the First Battle of Bull Run or the Second Battle of Bull Run after the name of a stream that passed through the battlefield. Thus, Booth calling the battle Bull Run should have exposed him as a Northerner. Unfortunately, Eyepatch the Confederate says he earned his medal at Bull Run. So either Eyepatch is also a Northerner posing as a Confederate, or the writers were unaware of the difference in names for this battle.

- Eyepatch’s claim that Booth’s uniform “isn’t what we wore there [at Bull Run]” is confusing. I’m guessing he’s trying to say that the 1st Texas Infantry, the regiment shown on Booth and Herold’s caps, wasn’t at the Battle of Bull Run. If Eyepatch was talking about the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861, he would be correct. The 1st Texas Infantry hadn’t been formed when this battle was fought. However, the 1st Texas Infantry did exist by the time the Second Battle of Bull Run occurred in 1862 and was a part of that battle. So there’s no reason for Eyepatch to have questioned Booth and Herold’s service by their clothing alone.

- This episode really tests the viewer’s suspension of disbelief by having Booth announce his identity to a giant group of people while a wanted poster offering $50,000 for his capture is a few feet away from him. It further establishes that a Union office is located across the road from the ferry landing in Port Royal. It even implies that Eyepatch is going to rat Booth out since he asks about the office immediately after spitting on Booth and condemning his actions. Worse yet, Booth reminds everyone at the ferry that there is a reward on his head when he yells to Jim Thornton, the Black ferry operator giving him a look, that folks like him “don’t get rewards.” In this scene, Booth is essentially begging one of these men to turn him in, and it’s beyond belief that none of them did.

- This episode shows Dr. Mudd being arrested by Stanton himself after Mary Simms tells the Secretary about how Mudd knew the assassin and John Surratt. Since Mary Simms is a fictional version of a real person who was not there in 1865, it goes without saying that this scene is fictional. Dr. Mudd was first visited by troopers on April 18 and questioned about the two visitors he had during the early morning hours of April 15. On April 21, Dr. Mudd was taken to Bryantown for further questioning but allowed to return home on April 22. Then, on April 23, the doctor was arrested and taken up to Washington for more questioning and eventually put on trial as a conspirator.

- Stanton and the 16th NY question ferryman Jim Thornton in Port Conway, who tells them about Booth and Herold crossing the river earlier that day. In reality, when the 16th NY (without Super Stanton, of course) arrived in Port Conway on April 25th, they learned from William Rollins that a wounded man matching Booth’s description crossed the Rappahannock the day before. William’s wife Bettie provided the vital information that Booth was accompanied by Willie Jett, who was likely to be found in Bowling Green. Since they cut William Rollins from the series, it makes sense for this information to come from Thornton. However, it is funny to note that after Thornton tells Stanton that Willie Jett can be found in Bowling Green, rather than crossing the river to actually go to Bowling Green after him, Stanton and the troopers head back north – the opposite direction. Never fear, however. Two scenes later, Stanton and the soldiers are magically in Bowling Green despite having never crossed the Rappahannock River.

This was truly a massive episode to cover in a historical review. I enjoyed that Booth and Herold were the central figures in this episode and that the manhunt for them was finally the main plotline. However, it was disappointing that the most Manhunt-esque episode of the whole series was essentially nonstop deviations from the actual facts. I’m once again filled with the opinion that this series would have been so much better suited if it had not been called Manhunt and thus hadn’t inherited an expectation for accuracy. Had this been a differently named Edwin Stanton miniseries, then it would be much easier to accept all the fiction like any other Hollywood take on reality. But Manhunt, the book, is nonfiction, and so the expectation is that Manhunt, the series, would try its best to be as well. But, sadly, this was not the case. Don’t get me wrong, I still enjoy the show for what it is, but this episode, more than the others, made me yearn for what it could have been.

I’ll see you back sometime in the future for a review of the penultimate episode, Useless.

Dave Taylor

such a disappointment a disservice to history buffs who have learned so many falshoids its embarrassing for Lincoln Community

Couldn’t agree with you more. This was not the Manhunt I expected due to the name and reference to the author. Eventually, I realized this is a fictional story with some references to real events. But, this was NOT and should not have been named Manhunt.

You are very kind to find positive things to say about this series. I might see them if I were more charitable, but I am blinded by the continual decisions to rely on a TV writer’s judgment on what will be interesting and laudable under our present sensibilities rather than by what was so ably chronicled in Swanson’s book. How anyone could fail to find the actual story completely fascinating is beyond me.

Unfortunately, viewers will probably think it is the truth.

Great review, though, Dave!

Do you have a review of Episode 6 and 7?

Very belatedly, Whitney, I wanted to let you know that I have finally finished my reviews of the last two episodes. Thanks for your patience.

https://lincolnconspirators.com/reviews-of-manhunt-2024/