Saturday, June 3, 1865

Previous Session Trial Home Next Session

Proceedings

The court convened at 10 o’clock.[1]

Present: All nine members of the military commission, the eight conspirators, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, Assistant Judge Advocates Bingham and Burnett, the recorders of the court, lawyers Frederick Aiken, John Clampitt, Walter Cox, William Doster, and Thomas Ewing.

Absent: Reverdy Johnson and Frederick Stone

Seating chart:

The prisoners were seated in the same manner as the day before.

The reading of the prior day’s testimony was completed at 12 o’clock.[2]

Testimony began

Leonard J. Farwell, a former governor of Wisconsin, testified that, on the night of Lincoln’s assassination, he rushed to the Kirkwood House hotel to warn and protect Vice President Andrew Johnson. Farwell banged on Johnson’s door and yelled, “Governor Johnson, if you are in the room, I must see you.” Though he was not positive, Farwell believed Johnson’s door was locked. Farwell was called to the stand by William Doster, George Atzerodt’s attorney. Farwell stated that he did not see anybody lying in wait anywhere near the Vice President’s door and that no one suspicious approached the room during his time there. Doster hoped to use Farwell’s testimony to show that the Vice President was never really in danger as George Atzerodt never intended to go through with his assignment from Booth.[3]

John B. Hubbard, a detective in the National Detective Police, testified that he was on duty watching over the conspirators during their trial and imprisonment. William Doster, Lewis Powell’s lawyer, asked Hubbard to recount a conversation he had with Powell. Assistant Judge Advocates Henry Burnett and John Bingham both objected to the admission of a defendant’s declarations. Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, after being reassured that the conversation was being introduced as evidence of insanity, broke with his assistants stating that while, as a confession, nothing Powell said was competent, his words could be used by the defense to prove insanity. Holt suggested Powell’s words be allowed, “only so far as they may aid in solving the question of insanity raised by the counsel.” Bingham and Burnett removed their objection and Hubbard was allowed to continue. According to Hubbard on the third or fourth day of the trial as Powell was being led out of the court room, the conspirator said he wished the court would “make haste and hang him,” and that he would “rather be hung than come back.” Hubbard also testified that about a week ago Powell told him he had been constipated ever since he had been brought to the prison.[4] Doster hoped that Powell’s desire for death and extreme constipation would help prove him to be of unsound mind.

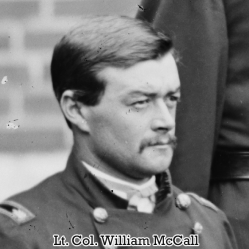

Lt. Col. William H. H. McCall, a member of Gen. Hartranft’s staff at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary, testified that he had charge of the conspirators. McCall was asked about Lewis Powell’s bowel movements during the course of his imprisonment. According to McCall, Lewis Powell had been constipated from April 29th until the prior evening, June 2nd where he had his first bowel movement.[5] At the time, it was believed that prolonged constipation was a symptom of insanity which is why Doster asked McCall to testify on the matter.

John E. Roberts, a detective with the National Detective Police, testified that he was also on duty watching over the conspirators during their trial and imprisonment. Roberts stated that on May 19th, the day of the trial when Lewis Powell was dressed up in the clothes he was wearing when he attacked Secretary Seward, he was in charge of putting the irons back onto the conspirator. Roberts testified that Powell said, “they were tracing him pretty close and that he wanted to die.”[6]

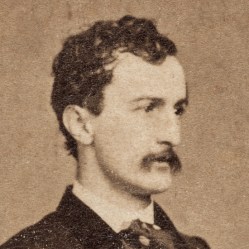

John W. Dempsey, a lieutenant in the Veteran Reserve Corps, was recalled for the prosecution after previously testifying on May 19th. Lt. Dempsey reiterated his earlier testimony stating he had been present at Mrs. Surratt’s boardinghouse after her arrest. While searching the house he came across a framed image which drew his attention. After opening up the frame, Dempsey found a photograph of John Wilkes Booth hidden behind the displayed image of “Morning, Noon, and Night”. While the frame and decorative image had already been entered into evidence, the photograph of Booth was not present during Dempsey’s earlier testimony. This time the photograph was in the court room and was entered into evidence.[7] When Anna Surratt had testified on May 30th, she had admitted that the picture of Booth had belonged to her and that she hid it due to her brother John’s objections.

The photograph of John Wilkes Booth, found hidden behind another picture at the Surratt boardinghouse, was entered into evidence as part of Exhibit 57a.

James R. O’Bryon, the chief usher at Ford’s Theatre, was asked about the condition of the locks on the theater boxes. O’Bryon stated that he had known the lock to Box 8 had been broken from quite some time before the assassination. He stated that the door to Box 8 was pretty tight so he never felt the need to tell anyone about the broken lock. O’Bryon said he did not know anything about the condition of the lock to Box 7. He supported the statement of Major Rathbone by stating the door to Box 8 was generally left open once it was occupied. In addition, O’Bryon testified that there was no lock on the vestibule door which led to Boxes 7 and 8.[8] Thomas Ewing used O’Bryon’s testimony to show that no malevolent act had been done to the locks of the theater boxes in preparation for Lincoln’s arrival, something the prosecution implied Edman Spangler might have done.

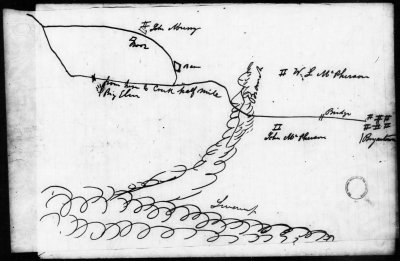

Dr. Joseph Blandford, Dr. Mudd’s brother-in-law, was recalled by the defense after previously testifying on May 29th. Dr. Blandford was presented with a map of Maryland on which he had labeled the whereabouts of Surrattsville, Dr. Mudd’s house, and Pope’s Creek. He had also drawn some of the roads between these places that had not been formerly included on the printed map. Dr. Blandford also presented a hand drawn plat he had made of the road leading from Dr. Mudd’s house to Bryantown. The drawing contained the locations of some of Mudd’s neighbors in the vicinity of Bryantown. Dr. Blandford was asked about visible the road was from the perspective of the different homes and about the relative distances between them.[9] The hand drawn plat was used to give some background knowledge and perspective regarding the path Dr. Mudd and David Herold took on their way to and from Bryantown on April 15th.

The map of Maryland with Dr. Blandford’s notations (pictured above) was entered into evidence as Exhibit 77. Dr. Blandford’s hand drawn plat of the road leading to Bryantown (pictured below) was entered into evidence as Exhibit 78.

Break

Following Dr. Blandford’s testimony, the court decided to take their normal one hour recess for lunch. During this time all of the conspirators were returned to their cells. At 2 o’clock, the court reassembled and testimony was resumed.[10]

Testimony resumed

Susan Stewart, a possibly African American[11] resident of Charles County, testified that she lived at John Murray’s property on the road to Bryantown. Stewart stated that on the afternoon of April 15th, she saw Dr. Mudd riding his horse from the direction of town. The doctor was alone and was taking the side farm road that he often used when heading back to his home. Stewart saw Dr. Mudd converse briefly with her neighbor, George Booz. Stewart stated that she did not see anyone with Dr. Mudd or anyone on the main road but admitted that she really didn’t, “take notice of the [main] road.”[12] The purpose of Stewart’s testimony was to counter the earlier testimony of Becky Briscoe who claimed David Herold waited for Dr. Mudd above Bryantown and then rode back with the doctor to his farm.

Primus Johnson, an African American resident of Charles County, testified that he saw Dr. Mudd ride to and back from Bryantown on the day after Lincoln’s assassination. Johnson noted that while Dr. Mudd was alone both times, there was another man who was riding down the road to Bryantown at around the same time. This other man (David Herold) rode back up the road without Dr. Mudd. According to Johnson, Dr. Mudd was in Bryantown for about an hour and a half before he saw him near the home of George Booz.[13] While Primus Johnson’s estimate of Dr. Mudd spending an hour and a half in Bryantown does not fit the timeline of other witnesses, he did contribute to disputing the testimony of Becky Briscoe who claimed David Herold waited for Dr. Mudd and the two rode back to his farm together.

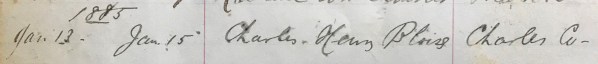

Charles Bloise, an African American resident of Charles County, Maryland, testified that he had spent most Saturdays and Sundays at the Mudd farm in 1864. Bloise’s wife, Julia Ann, worked as a servant in the Mudd home and had previously testified as a defense witness on May 29th. Bloise was asked essentially the same questions that had been posed to his wife. He echoed her responses that he had never seen anyone hiding in the woods around the Mudd farm and that the reputation of the prosecution witnesses Mary Simms and Milo Simms was poor. When Thomas Ewing asked Bloise about Dr. Mudd’s reputation as a master over his servants, Bloise replied that Dr. Mudd was a “first-rate man”. Bloise had never heard of Dr. Mudd whipping any of his servants or threatening to send them South. It’s important to point out that by the time Bloise’s wife started working for Dr. Mudd slavery had been abolished in Maryland. Julia Ann Bloise worked as a paid servant rather than as a slave which would explain Dr. Mudd’s improved treatment. The prosecution also made this distinction asking Bloise if he had heard about Dr. Mudd having shot one of his servants. When Bloise stated he had heard about it, the prosecution asked him, “Do you think that is first-rate business?” Bloise replied, “I do not know about that.”[14] It is interesting to note that while Charles and Julia Ann Bloise acted as defense witnesses for Dr. Mudd, Charles’ brother Frank, his wife Eleanor, and their daughter Becky Briscoe were all called as prosecution witnesses against him.

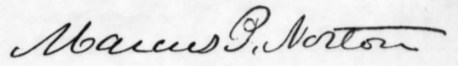

Assistant Judge Advocate Henry Burnett then announced that while the case of the prosecution had been closed, he desired permission to examine a witness of great importance to the government’s case. Walter Cox, attorney for Michael O’Laughlen, objected to the request stating that, while the defense had agreed that further testimony regarding the overall conspiracy of the assassination would be allowed, it was accepted that the prosecution had ceased their case against the individual conspirators. Cox stated that it was against the practice of civil courts to allow testimony trying to prove the charges after a case had been closed. Col. Burnett replied that it was the custom of military courts that witnesses might be recalled or new witnesses examined at the discretion of the court. One of the members of the military commission then asked Burnett which conspirator was to be affected by new testimony. Burnett replied that his witness would implicate George Atzerodt, Michael O’Laughlen, and Dr. Mudd in regards to their connection with Booth. Thomas Ewing, Dr. Mudd’s attorney, stated that he was willing to leave the matter to the court’s discretion granted he would be given ample time to summon and interview witnesses of own in regards to this new testimony. Col. Burnett replied that his desire to call this witness now was to give the defense the time they needed to meet this evidence. The commission then granted Col. Burnett’s application and Marcus P. Norton was called as a prosecution witness.[15]

Marcus P. Norton, a patent lawyer from Troy, New York, testified that he had resided at the National Hotel in Washington, D.C. between January and March of 1865. During his time at the National, Norton became acquainted with the appearance of John Wilkes Booth who also stayed at the hotel. Norton stated that during his time at the National he saw John Wilkes Booth in separate conversations with two men he identified as George Atzerodt and Michael O’Laughlen. These conversations occurred in the public hall. According to Norton, he saw Booth with O’Laughlen four or five times but he knew nothing of what the men talked about. The witness also believed he saw George Atzerodt with Booth two times and during one of those times Norton happened to be seated near enough to the pair to have overheard a couple sentences. Norton testified that part of Atzerodt’s and Booth’s conversation was something along the lines of, “if the matter succeeded as well with Mr. Johnson as it did with old Buchanan, their party would get terribly sold.” In addition to these statements, Norton claimed that on the 3rd of March Dr. Samuel Mudd came bursting into his hotel room. On seeing Norton in the room, Dr. Mudd apologized, saying he was looking for the room of John Wilkes Booth. Norton suggested Mudd try upstairs and watched Dr. Mudd as he departed his room and made his way down the hall. While he was a bit uncertain about the dates he observed the conversations between Booth, Atzerodt, and O’Laughlen, he set the date of Dr. Mudd’s intrusion as March 3rd, due to his arguing a case before the Supreme Court on that date.[16] During their cross-examination of Norton, the defense demonstrated that he could not remember much else regarding his observations and interactions with the conspirators. He could not describe the clothing of the men and could not explain how he could confidently identify three men he only saw in passing in a crowded hotel. The defense was incredulous that Norton could remember pieces of sentences that he overhead two months prior. In future days of the trial, Thomas Ewing, a lawyer for Dr. Mudd, brought witnesses forward to discredit Norton and demonstrate that his reputation for honesty was considered to be poor. The prosecution would counter these attacks with witnesses of their own who testified about Norton’s reliability. Marcus Norton’s testimony elicited one of the few documented instances of overt emotion on the part of Dr. Mudd. As Norton testified, Dr. Mudd’s, “countenance changed rapidly, the blood mounted to his face, and he compressed his lips with ill-concealed emotion.”[17]

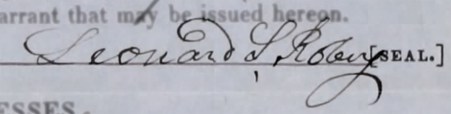

Leonard Smallwood Robey, a farmer living near Bryantown, Maryland was called a defense witness. Robey testified that he visited Bryantown on the afternoon of April 15th. While he heard the news of Lincoln’s assassination from his neighbors and the soldiers stationed at Bryantown, Robey claimed the identity of the assassin was not clearly known. People told him that the assassin was someone connected to the theater but he could not get a name. According to Robey, even the soldiers he asked were unaware of the name of the assassin. It wasn’t until about dusk, as he was getting ready to go back home, that Dr. George Mudd told him that Booth had been the one who did it. Robey was also asked about the reputation of Daniel J. Thomas, the prosecution witness who had claimed Dr. Mudd had told him in March of 1865 that Lincoln and all the Union men in Maryland were to be killed soon. Robey gave his opinion that Thomas was the kind of man who would imagine things and then bring himself to believe they are facts.[18] The point of Robey’s defense testimony was to support the argument that the identity of John Wilkes Booth as Lincoln’s assassin was not known for certain in Bryantown on April 15th when Dr. Mudd visited. However, this contradicts the testimony of Lt. Dana who testified that by 1:15 pm the whole village knew the name of Lincoln’s killer.

Edward D. R. Bean, a merchant living in Bryantown, testified that Dr. Mudd visited his store after the assassination of Lincoln. While in Bean’s store, Dr. Mudd purchased some calico fabric. According to Bean, the two men discussed the news of Lincoln’s assassination to which Dr. Mudd said, “I am very sorry to hear it.” Like the previous witness, Bean claimed to not have be certain of the assassin’s identity at the time. He initially believed the assassin was a man named Boyle who had once killed a Union solider in the area. Bean did not believe he had learned Booth was the man until Dr. George Mudd told him at a later time.[19] Bean was less than certain in most of his testimony. The merchant did not even commit to the fact that April 15th was the day Dr. Mudd came to his store, even though it was.

John R. Giles, a bartender at Rullman’s Hotel in Washington, D.C., testified that he had seen Michael O’Laughlen and his band of friends at his bar on the evening of April 13th. According the Giles the men left the bar for a bit and then came back around 10 o’clock at which point Giles joined them in their celebratory activities (i.e. drinking). Giles left Rullman’s in the company of the men after the bar closed and was with them until 1 o’clock in the morning. On the next day, April 14th, O’Laughlen and some of the others returned to Rullman’s and stayed there from 7 o’clock until around 11 o’clock. Giles testified that O’Laughlen was at Rullman’s, and had been there for hours, when news of the assassination reached them.[20] Giles testimony supported the earlier testimonies of O’Laughlen’s friends/drinking buddies Bernard Early, Edward Murphy, Daniel Loughran, George Grillet, Henry Purdy, and John Fuller. All of these men countered the government’s claim that Michael O’Laughlen had been seen lurking around Secretary Stanton’s house on the evening of April 13th. During Giles’ testimony, the newspapers commented on the bartender’s large frame: “[The witness is of a ponderous size – his body taking up the whole of the stand.]”[21]

David C. Reed, a Washington, D.C. tailor, was recalled to the stand as a defense witness after previously testifying for the prosecution on May 15th. Reed reiterated his earlier testimony about having seen John Surratt in D.C. on the day of Lincoln’s assassination. Frederick Aiken, Mary Surratt’s attorney showed Reed Exhibit 72, the photograph of John Surratt. Reed stated that Surratt’s hair was shorter when he saw him that how it was in the photograph. Reed also said he did not take notice if Surratt was wearing whiskers or not.[22] What purpose Aiken had in recalling Reed to the stand is not known as he provided no help to the defense. It almost seems like he was hoping Reed, upon seeing an image of John Surratt, would suddenly change his mind about the identity of the man he saw. Either that or Aiken was hoping that Reed would testify something about Surratt’s facial hair that he could counter him on. Neither of these scenarios occurred and David Reed was essentially given time by the defense to further the prosecution’s claim that John Surratt was in D.C. on the day of the assassination and that Mary Surratt may have lied to authorities about her son’s whereabouts.

Anna F. Ward, a schoolteacher in Washington, D.C., testified that she had known Mary Surratt for 6 to 8 years. Ward was asked about Mary Surratt’s eyesight and she stated that Surratt was nearsighted like herself. Ward described instances where Mary Surratt passed her on the street without recognizing her, asked her to read a letter when the gaslights were low, and commented to Ward that they both had a hard time seeing. This testimony was to help explain why Mary Surratt failed to identify Lewis Powell when he showed up at her house following the assassination. Ward was also asked about her contact with John Surratt who had sent four letters to Ward in the days prior to the assassination. Two of the letters were meant for Mrs. Surratt and Ward delivered them to her. Ward testified that these letters were postmarked from Montreal, Canada. Ward also admitted to having inquired about any vacant hotel rooms at the Herndon House hotel around February of 1865 as a favor to John Surratt.[23] Lewis Powell later occupied the room Anna Ward inquired about but she claimed she never knew its intended renter.

Joseph J. Sessford, Ford’s Theatre’s box office assistant and ticket seller, testified that he had been at the theater from 6:30 pm on the night of the assassination. According to Sessford, no one except for the Presidential party reserved any of the theater boxes on the night of April 14th.[24] Sessford’s testimony was to counter the prosecution’s unsupported claim that others had requested some of the theater boxes on April 14th but had been turned away.

William Doster, Lewis Powell’s lawyer, submitted an application requesting that Dr. Charles Nichols of the Government Asylum for the Insane be allowed to examine Powell for the sake of determining his sanity. This application was approved by the court. Doster also made an application that the court not close the defense on the part of Lewis Powell until his father, George C. Powell, could be summoned from Florida to testify about Powell’s childhood and family history. In addition, Doster wanted to make sure that Captain Dolly Richards and John Grant both of Virginia were heard from before the court forced the defense to close.[25] Aside from a brief mention of the name Powell during the testimony of Maggie Branson, this was the first time the court had been told that Lewis “Payne” was the son of a George Powell. Upon hearing this news, Assistant Judge Advocate John Bingham stated, “Then are we to regard that as an authentic statement, that the prisoner’s name is Powell?” Doster replied, “I have stated that his father’s name is Powell, and I take it for granted the inference will be drawn that that is the name of the prisoner.” Assistant Judge Advocate Bingham said that, in regards to the application, reasonable time would be allowed the defense to meet new evidence but that he was against postponement for want of distant witnesses. The Court agreed, with General David Hunter stating that ample time had been allowed to obtain witnesses.[26]

There were no other defense witnesses in attendance so the court adjourned at around 4 o’clock.[27]

Recollections

“The Commission met as usual. The day was intensely hot and the Commission room very uncomfortable. Nothing of note transpired. The Court adjourned early for want of witnesses.”[28]

Many years later, William Doster, George Atzerodt’s counsel, wrote how he tried to call President Johnson to the witness stand but had to resort to Governor Farwell:

“His part was to kill Mr. Johnson, he said. He had ample opportunity but did not intend to do it. His defense lay mainly in showing this — that he had abundant occasion to carry out such an intention had it existed, that the President was in his room all night, with the door open. The only witness who could have shown this was the President himself. I subpoenaed him to appear and testify, but he did not come. I issued another subpoena. He then sent me word through his private Secretary that he did not intend to come. That I should subpoena Governor Fairchild [sic] who had come to his room to inform him of the assassination. I did subpoena him, but his evidence was of course not sufficient to prove the condition of a room for the previous two hours. I pressed Mr. Johnson no further, for I did not care to irritate the very man who could pardon the prisoner, and also must have known that to Atzerodt’s unwillingness he was indebted for his life. The sequel showed, however, that he did not consider this.”[29]

Newspaper Descriptions

Mrs. Surratt

“[Miss Ward, after she had been on the stand, and was returning to the witness room, had to pass near Mrs. Surratt. As she neared the seat the accused took her fan from her face and looked towards the witness. They recognized each other, and the witness burst into tears and passed into the ante-room. Mrs. Surratt again put the fan before her face, and relapsed into her former position, with her head against the wall, the officer standing before her to screen her from observation.]”[30]

Lewis Powell

“Either from the languor from the great heat, or from some other cause, the heretofore erect figure of Payne is somewhat drooping; but his gaze is quite as unperturbed and bold as ever.”[31]

“Notwithstanding his apparent audacious self-possession in the Court Room, it is said he expresses the greatest aversion to sitting on exhibition in the prisoner’s dock.”[32]

“Payne’s counsel labored to prove to-day that the would-be assassin of Secretary Seward and his son Frederick has been suffering lately from constipation of the bowels. If the fellow had any ‘bowels of compassion’ they have probably been constipated ever since he was a child.”[33]

Dr. Mudd

“Mudd, whose case had begun to look favorable under Ewing’s zealous efforts, was evidently shocked at [Marcus] Norton’s statements. His countenance changed rapidly, the blood mounted to his face, and he compressed his lips with ill-concealed emotion.”[34]

Michael O’Laughlen

Note: Today was Michael O’Laughlen’s 25th birthday.

Visitors

“The court-room was densely crowded, it being almost impossible for another person to get in the room.”[35]

“Hon. Alfred Ely, of N.Y., is present.”[39]

“The trial of the conspirators still continues to attract crowds of spectators, notwithstanding the extreme heat of the weather makes the atmosphere of the court room by no means as agreeable to the olfactories as otto of roses or the spicy gales of Araby. Indeed, not to put too fine a point upon it, the air of the room during these hot summer days is positively sickening. At least three times as many persons are crowded into it as it should contain, and the result may be imagined.”[36]

“The fair sex, faithful to their ancient reputation for curiosity, furnish daily the largest number of spectators, and fill every nook and corner and chair, and even invade the sacred precincts of the lawyers’ tables and that of the reporters’ without any compunction of conscience. General Hunter, whose gallantry is equal to his bravery, was compelled to-day to caution the ladies to stand back, and not press forward between the prisoners and their counsel, which space the fair ones had began to consider their own, as if by pre-emption right, because they had been permitted from day to day to occupy it, to the annoyance and discomfort of lawyers, witnesses and reporters. Forbearance almost ceased to be a virtue, and the gentlemen interested, muttered, not loud but deep complaints at this innovation of the fair, yet not had the courage to object, till General Hunter, in his bland and kindly way, told the ladies they must keep back, and directed the officers to clear the passage way. The effect of this order was to render all the prisoners visible to every spectator, which could not be done when the ladies crowded in front of Mrs. Surratt’s seat, to such an extent as to completely hide her from view, except to those immediately around her.”[37]

“Miss Anna Surratt, daughter of the accused, entered the court-room about half past 1. She sat with her veil over her face, but not weeping as on yesterday. Miss Surratt is about twenty years of age. She is dressed in a dark dress, black silk mantle, white straw hat trimmed with black ribbons, a lace veil, which covers her face, white collar, and sits with her head leaning over the railing, her eyes fixed upon the floor. She appears to be in great trouble, and attracts much attention, but keeps her head down and her veil over her face. She presents quite a neat appearance, and, by some, is thought to be quite pretty.”[38]

Previous Session Trial Home Next Session

[1] John F. Hartranft, The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution, as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft, ed. Edward Steers, Jr. and Harold Holzer (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 113.

[2] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1865, 2.

[3] William C. Edwards, ed., The Lincoln Assassination – The Court Transcripts (Self-published: Google Books, 2012), 874 – 876.

[4] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 876 – 877.

[5] Ibid., 877 – 878.

[6] Ibid., 878.

[7] Ibid., 878 – 880.

[8] Ibid., 880 – 881.

[9] Ibid., 881 – 885.

[10] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1865, 2.

[11] Due to racial attitudes of the time, African-American witnesses were identified in the trial transcript with the inclusion of the word “(colored)” after their names. While the official trial transcript does not make this notation in the case of Susan Stewart, several newspapers who sent correspondents to the courtroom did include this description for her. Among the newspapers who reported Susan Stewart as being African American were the Daily National Republican (D.C.), Constitutional Union (D.C.), New York Tribune, and Philadelphia Inquirer.

[12] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 885 – 886.

[13] Ibid., 886 – 887.

[14] Ibid., 887 – 889.

[15] Ibid., 889 – 890.

[16] Ibid., 890 – 898.

[17] The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), June 5, 1865, 4.

[18] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 898 – 901.

[19] Ibid., 901 – 904.

[20] Ibid., 904 – 906.

[21] Daily Constitutional Union (Washington, D.C.), June 5, 1865, 1.

[22] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 906 – 907.

[23] Ibid., 907 – 910.

[24] Ibid., 910 – 911.

[25] Ibid., 911.

[26] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), June 5, 1865, 1.

[27] Hartranft, Letterbook, 113.

[28] August V. Kautz, June 3, 1865 diary entry (Unpublished diary: Library of Congress, August V. Kautz Papers).

[29] William E. Doster, Lincoln and Episodes of the Civil War (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1915), 274 – 275.

[30] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1865, 2.

[31] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1865, 2.

[32] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1865, 2.

[33] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1865, 2.

[34] The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), June 5, 1865, 4.

[35] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1865, 2.

[36] The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), June 5, 1865, 4.

[37] The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), June 5, 1865, 4.

[38] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1865, 2.

[39] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1865, 2.

The drawing of the conspirators as they were seated on the prisoners’ dock on this day was created by artist and historian Jackie Roche.

Pingback: The Trial Today: June 3 | BoothieBarn

Dave,

You have given us a deeply appreciated contribution to the study of the Lincoln Assassination. I’m curious as to your take on the testimony that the door to Box 8 was left open during the performance. If this is true, how would Booth have remained unseen while securing the brace against the door? Can we assume that, like some other pieces of testimony, this was an error of memory?

Thank you again. This all has been absolutely riveting and I am learning so much new information.

Sincerely,

Dave G

In his statement to authorities on April 17, Major Rathbone states more than once that the Box 8 door remained open during the performance. With all attention on the stage, I think it was easy enough for Booth to enter from the vestibule door and bar it without being seen by those in the box, especially since the door to Box 8 was not the one immediately behind the President. I’m sure Booth had to act quietly, though.

Thank you, Dave.

I never realized Dr. Mudd took a shortcut on the farm lane going south from his house before intersecting the main road going to Bryantown. The hand-drawn map of Dr. Joseph Blandford does not depict the Dr. Sam Mudd house. I suspect the Sam Mudd house was on the farm lane (upper road in the drawing) at the upper left corner close to the intersection of the farm lane and the main road. Is that reasonably correct? Could that be the same lane Booth and Herold took as they exited the farm Saturday afternoon?

I’ve long thought the vitriol of the CW newspapers was at times perhaps greater than that of today’s press. However, the following example, quoted above, from the Daily National Republican certainly made me laugh. Speaking of Lewis Powell, they wrote, “If the fellow had any ‘bowels of compassion’ they have probably been constipated ever since he was a child.”[33] One of the best quotes ever!

i noticed and thought the same thing, “Fake News” is not new. 150 years later things are pretty much the same, only the method of delivering message different.

Dennis,

The hand drawn map produced by Dr. Blandford only shows a small portion of the route taken by Dr. Mudd on his was to and from Bryantown. For reference here is a modern aerial map.

Bryantown is marked and the red pin marks the location of George Booz’ home, which is also shown on Dr. Blandford’s map. The blue pin in the modern map is Dr. Mudd’s house. So, as you can see, Dr. Blandford’s map only shows the area of the route Dr. Mudd took in the vicinity of Bryantown, not near his farm.

Pingback: Formerly Enslaved Voices in the Lincoln Assassination Trial | LincolnConspirators.com