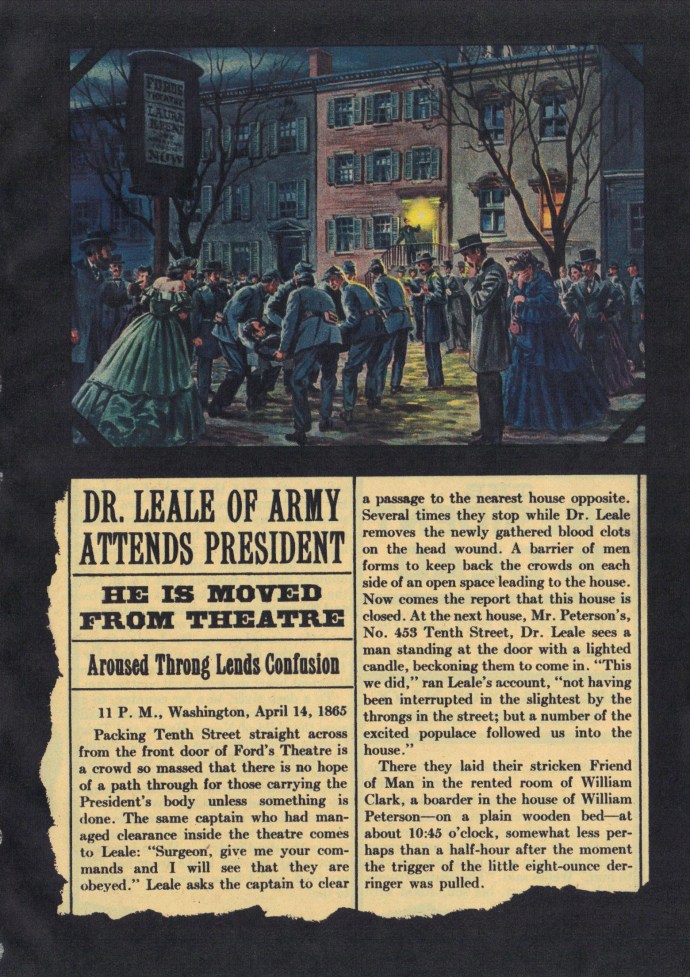

After being fatally shot at Ford’s Theatre, the unconscious body of our 16th President was carefully carried across the street to the home of William Petersen. He was brought into the bedroom of boarder William Clark, who was out of town for the night, and laid diagonally across the bed. It would be in this room that Abraham Lincoln would pass away at 7:22 am the next morning. During the almost nine hours that Lincoln spent in the Petersen boardinghouse, dozens of Washington’s elite made an appearance at his death chamber to pay their last respects.

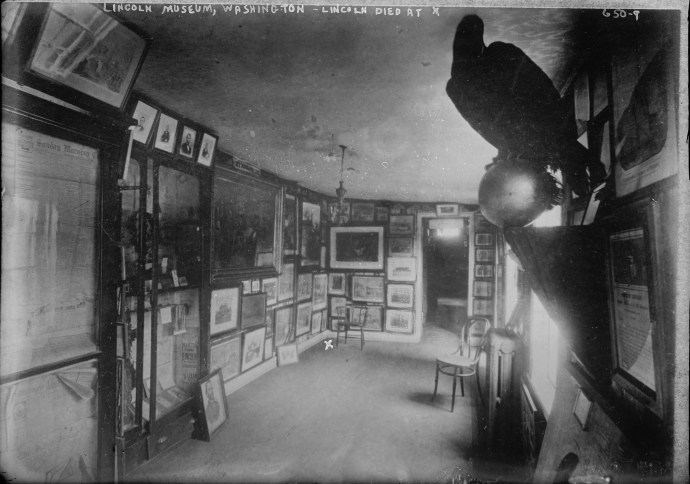

Those who have visited the restored Petersen House across from Ford’s know that the room the President died in is small. It measures 9′ 11″ wide by 17′ 11″ long. Despite its small size, the room in which Lincoln died has gained the moniker of the “Rubber Room”. This is due to the way in which the small room stretched to unrecognizable proportions in the various engravings, lithographs, and prints that were made following Lincoln’s death. There’s a wonderful chapter in the edited book, The Lincoln Assassination: Crime & Punishment, Myth & Memory by Lincoln authors Harold Holzer and Frank Williams that explores the “Rubber Room” phenomenon in detail. In summation, the various artists of deathbed illustrations were forced to make the room appear larger and larger in order to cram more and more dignitaries into one, defining scene. Here are just a few depictions of how the small bedroom photographed above became a massive hall for the mourners.

As fancifully large as these depictions are, they all pale in comparison with the magnitude of a painting by Alonzo Chappel. His piece was a collaboration with another man by the name of John B. Bachelder, who served as the massive painting’s designer. Entitled, The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln, Chappel and Bachelder wanted to depict all of the notable people who visited Lincoln that night at the same time and, in doing so, stretched the rubber room into unparalleled proportions:

In all, the painting contains the images of 47 people in the back bedroom of the Petersen House. The room has grown so much to accommodate all of these souls, that the walls started duplicating themselves. It appears that the known lithograph that hung in the room “The Village Blacksmith” gave birth to a smaller, mirrored version of itself as the walls stretched out:

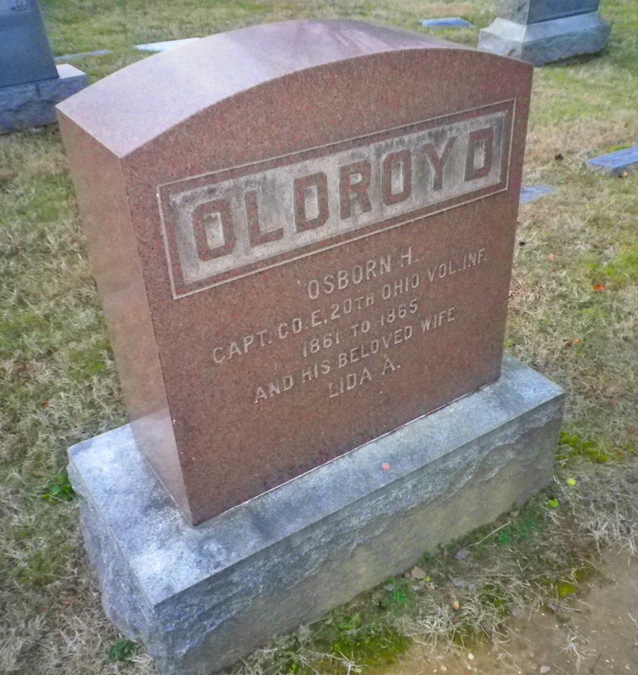

Just for fun, let’s say that all of the individuals pictured in Chappel’s painting were present in Lincoln’s death room at the same time. Using modern measurements, William Clark’s room has an area of 177 square feet. We’ll subtract 20 square feet for the bed on which Lincoln died since that is the only piece of furniture that we know had to remain in the room. That leaves us with 157 square feet. We’ll divide that by the 46 visitors in Chappel’s painting (we’re not including Lincoln since he was laying on the bed). That gives everyone in the room a cozy 3.4 square feet all to themselves. To give you some perspective, in a well ventilated, outdoor setting like a crowded rock concert, the accepted bare minimum amount of space per person is 7 square feet. For many interior settings the common rule of thumb is at least 9 square feet per person. If everyone in this painting tried to get into William Clark’s room at the same time, they would be literally crammed together like sardines in a can. What’s more, this imaginary calculation does not include the other furniture in the room, the large amount of space that the women’s hoop skirts would require, and the measurements by Osborn Oldroyd which, if correct, would lower the room’s original square footage from 177 sq. ft. to 161.5 sq. ft.

Despite the laughable morphing power of the small bedroom, Chappel’s painting was considered one of the best depictions of the death chamber of Abraham Lincoln. The details for each person were exquisitely done and so life like. Of course, there was a very good reason why Chappel was able to paint such realistic versions of the many people who visited Lincoln that night. The designer of the piece, John Bachelder, had convinced many of the people in the painting to sit for photographs in the poses that Chappel wanted to paint. Notable figures like Andrew Johnson, Edwin Stanton and even Robert Todd Lincoln posed in Mathew Brady’s studio in ways that the painting would later recreate.

In addition to the cabinet members and politicians who posed for Bachelder and Chappel, there were also two individuals whose presence at the Petersen House was never questioned but, for some reason, they did not appear in other depictions of the President’s death. These two neglected people were Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln’s guests for the evening, Major Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris.

Both Henry and Clara posed for their own photographs and were worked into the painting. Clara is given a degree of prominence in the painting standing just behind the grieving Robert Todd Lincoln:

Henry, on the other hand, is removed from the chair he posed in and is literally sidelined to the far left of the painting. He is almost obscured by the dark edge and frame, perhaps an ironic foreshadowing of the darkness that would later compel him to murder Clara and try to take his own life.

Alonzo Chappel’s work, The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln, is a work of contradiction. The painting simultaneously contains the most detailed and accurate depictions of the individuals who visited the dying President while also demonstrating extreme hyperbole and imprecision with the seemingly ever expanding walls of William Clark’s bedroom. It’s a beautiful yet unbelievable painting and it exemplifies the “Rubber Room” phenomenon in a truly unsurpassed way.

References:

Civil War Art Entry for The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln

Library of Congress print of The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln (slight differences)

Looking For Lincoln: The Making of an American Icon by the Kunhardts

The Lincoln Assassination: Crime & Punishment, Myth & Memory edited by Harold Holzer, Craig Symonds, and Frank Williams

Recent Comments