On March 4, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated for a second time following his reelection in November of 1864. With hopes that an end to the Civil War was in sight, Lincoln gave a historic speech addressing how the practice of slavery had caused the war, and expressing his hopes for a reconciliation between the two sides under a government free from this evil. Lincoln finished his speech with the iconic words:

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

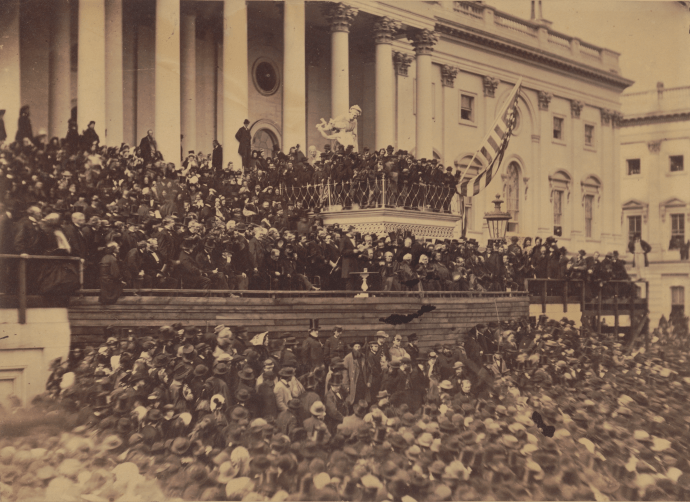

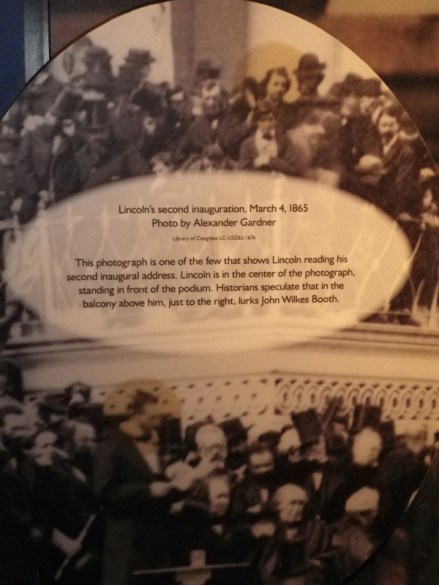

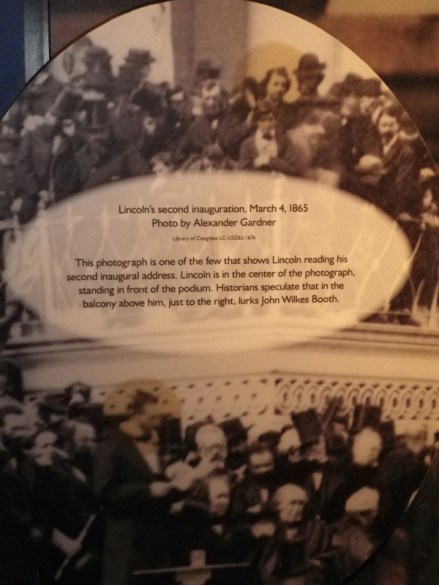

Noted photographer Alexander Gardner documented the scene of Lincoln’s second inauguration, much like he did four years earlier. Yet the circumstances were more difficult this time around. The day was mostly marked with overcast skies and drizzling rain. At some points, the sky would brighten and Gardner would attempt to photograph the scene. Yet, several of Gardner’s attempts resulted in less-than-ideal photographs of the President. Whether it was an incorrect focal length or issues developing the wet plate later, only a limited number of shots captured Lincoln well. As a result, you generally only see the image of Lincoln’s second inaugural that begins this post, as it was the best one that Gardner turned out (and even in that one, Lincoln is a bit blurry).

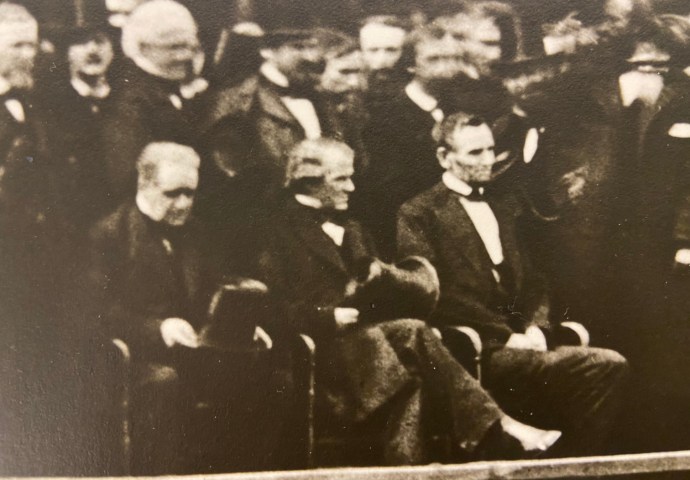

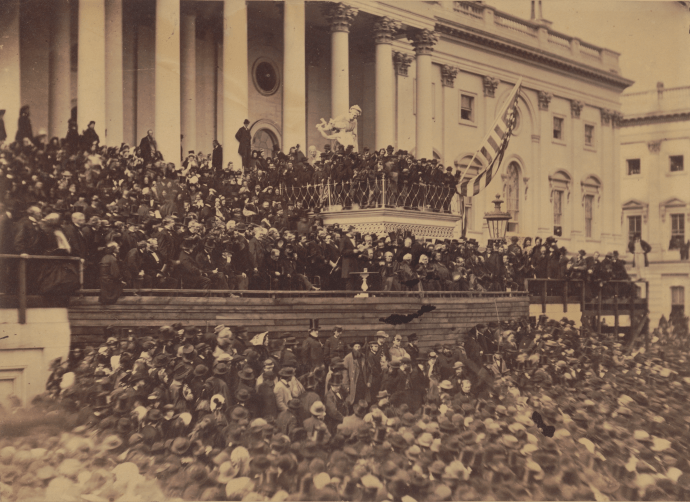

Yet there are a few other images of Lincoln’s second inauguration. Gardner attempted a series of photographs showing Lincoln seated at the front of the platform. The most successful attempt was the following, which shows the President seated next to his Vice Presidents, Andrew Johnson and Hannibal Hamlin.

This image probably does the best job of capturing Lincoln clearly. We benefit from the fact that Gardner used a large-format camera and wet plate photography, which results in incredible detail when done correctly. In many of Gardner’s images, even those where Lincoln is out of focus or blurred, members of the audience come through very clearly.

Among the crowded audience who gathered about the Capitol steps to hear Lincoln’s now-immortal words was the 26-year-old actor John Wilkes Booth. In a little over a month from when these photographs were taken, Booth would assassinate Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre.

John Wilkes Booth’s attendance at the Capitol during Lincoln’s second inauguration is referenced by the assassin himself. A little over a month later, Booth visited with an actor friend in New York named Samuel Knapp Chester. Booth had attempted to recruit Chester into his initial plot to abduct President Lincoln, but Chester had declined. On this visit, Booth convinced Chester that his plotting days were over. Still, Booth foreshadowed his true intent by saying to Chester, “What a splendid chance I had to kill the President on the 4th of March.” Booth clarified to Chester that he had received a “ticket to the stand on Inauguration day,” from his fiancée, Lucy Hale, the daughter of New Hampshire Senator John P. Hale. Booth was a celebrated actor who rubbed elbows with Washington elite. His presence on the stand at Lincoln’s inauguration would not have been odd in any way, especially if he had secured a ticket by way of a Senator’s daughter.

Combining the fact that John Wilkes Booth was present in the crowd at Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration and the high level of detail afforded by Alexander Gardner’s photographs, the question becomes, “Can John Wilkes Booth be seen in any of the pictures of the event?”

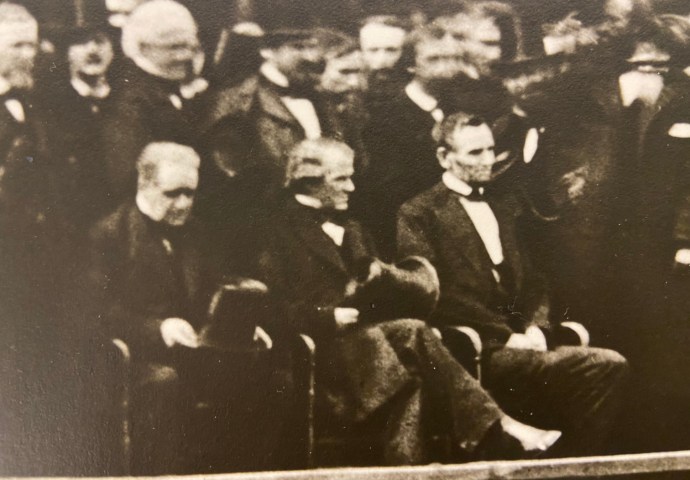

In 1956, a 90-year-old photography historian and collector named Frederick Hill Meserve believed he had found the assassin amongst the audience. Using images of the inauguration from his private collection, he published his findings in the February 13, 1956, issue of Life Magazine. Meserve, as stated in the article, “spent 60 of his 90 years collecting photographs of the Civil War era” and devoted his entire life to searching for and cataloging all the images of Lincoln that existed. He had previously published his compendium of Lincoln images with author Carl Sandburg in 1944. The image Meserve used in his identification of Booth in the crowd was not one of the ones he had published earlier. Instead, it was one of the lesser-known photographs of the second inauguration that was not widely known because the figure of Lincoln appears to have been accidentally obliterated by a thumbprint during the development process of the original plate. Here is the image:

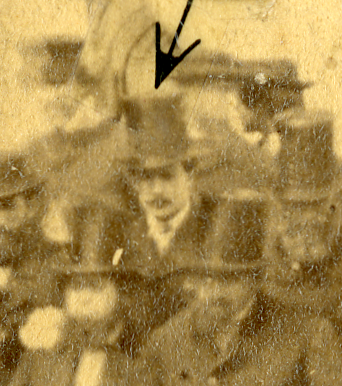

Meserve pointed out one of the figures, located on the platform above the President, wearing a top hat and a mustache:

In Meserve’s opinion, this figure was John Wilkes Booth. This was an intriguing idea from one of the country’s foremost experts on Lincoln photography. The figure does bear some resemblance to the actor-turned-assassin. But in the case of this particular image, the level of detail we need is still not quite there. I will also point out that Meserve went beyond identifying Booth in his Life Magazine article. He also identified Mary Todd Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s friend and sometimes bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon, theater owner John T. Ford, and conspirator Lewis Powell. While I agree with his identification of Johnson and Lamon, these other identifications are far more questionable. For example, there is no evidence to support the idea that Lewis Powell was in D.C. at the time of the inauguration. While part of Booth’s plot by this time, he was residing in a boardinghouse in Baltimore, and we have no statement that places him amongst the crowd. The figure Meserve points to as Powell looks a fair deal like him, but he is not featured near Booth. Instead, Meserve points to one of the figures against the wall below Lincoln as possibly being the future attempted assassin of Secretary of State William Seward.

Frederick Meserve died in 1962. Three years later, his daughter. Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt (author of the children’s book Pat the Bunny), released a coffee table-sized book with her husband, Philip, called Twenty Days: A Narrative in Text and Pictures of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the Twenty Days and Nights That Followed… The book utilized her father’s vast photography collection to tell the story of Lincoln’s death through images. In the book, she actually went a bit farther than her father when it came to identifying Booth and Powell at Lincoln’s second inauguration. Dorothy Kunhardt claimed to have identified several other members of Booth’s conspirators among the faces underneath the platform.

While intriguing, Kunhardt’s identification of the conspirators comes without evidence. Aside from Booth, we have no evidence that any of the other conspirators attended Lincoln’s inauguration. Historian Michael Kauffman points out in his book American Brutus that George Atzerodt had spent the previous night in Southern Maryland rowing across the Potomac, making it highly unlikely he would have been in D.C. at the time. Plus, in all the confessions Atzerodt later gave documenting the movements of his fellow conspirators, he never mentioned any of them being at the Capitol on this day. The same applies to John Surratt, who never mentioned witnessing the inauguration, despite later giving speeches about his involvement in Booth’s plot. In addition, most historians today consider Ford’s Theatre stagehand Edman Spangler innocent of any knowledge of Booth’s plot, making his inclusion in this supposed rogue’s gallery grouping fairly preposterous.

In the case of the conspirators, it appears that Meserve and Kunhardt were engaging in a bit of wishful thinking in their identifications. But what about the lead assassin? As we have seen, Booth acknowledged he was present for the event and was supposedly so close to Lincoln that he might have been able to kill the president if he had attempted the act. The figure Frederick Meserve pointed to is a possibility, but the detail is lacking.

Luckily, the image used by Meserve in his article is not the only one that appears to show this same figure. There is another Gardner photograph of the inauguration, one that is very similar to the most famous image of the event, but the focal point is off a bit so that Lincoln appears even blurrier.

While this makes for a poor image of Lincoln, the focus does give us a clearer image of the man just above Lincoln, whom Frederick Meserve identified as Booth:

This image still isn’t perfect, but it does give us more detail. There are certainly similarities between this man and the dapper, ivory-skinned, mustachioed actor who would later assassinate the President. In truth, it’s impossible to truly verify this man as Booth, but many have accepted Meserve’s identification. The textual evidence supports that John Wilkes Booth was there, and I am personally inclined to believe the basic resemblance in Meserve’s identification makes it possible that this could be John Wilkes Booth.

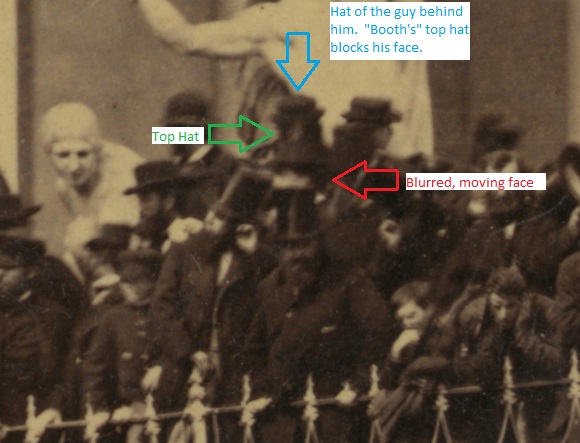

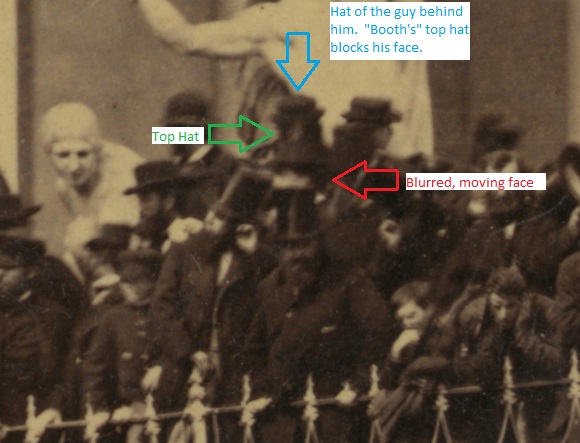

While many people have become aware of Booth’s possible inclusion in images of Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural, most are unaware that multiple images of the event were taken and that there are differences between them. As a result, many look at the most famous image of the inauguration searching for Booth in the crowd. However, in the most prolific image of the inauguration, the one that begins this article, the man Meserved identified as Booth cannot be seen clearly. The figure is partially obscured by the gentlemen in front of him straining to hear. Only the figure’s hat and the top of his head are visible.

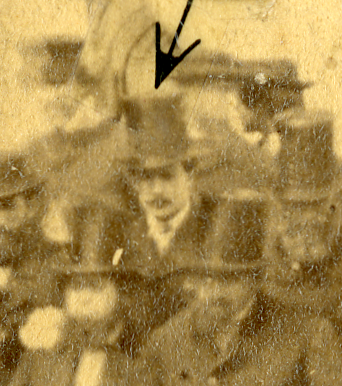

Since the “Booth” figure cannot be readily seen in the most famous image of the inauguration, many sources have selected a different man entirely and highlighted him as Booth. The Ford’s Theatre museum was once guilty of this. For several years, they had a large wall display of Lincoln’s second inauguration and included this inset:

The man they highlighted as Booth is not the same man we have seen in the other photos as being Booth. We know this because in the clearest picture of Meserve’s “Booth” the same man can be seen further down the line.

In my opinion, this figure bears even less resemblance to John Wilkes Booth than Meserve’s figure. This man has longer hair and appears to have a goatee or additional facial hair beyond Booth’s signature mustache. It also seems unlikely to me that Booth would have removed his hat during the proceedings. John Wilkes Booth was stylish and vain, retaining his fashion above all. While others might choose to remove their hats to perhaps better hear Lincoln’s words, such effort does not seem likely for the man who would soon kill him. Yet, it is this figure who is easily visible in the famous image of Lincoln’s second inauguration, who is highlighted on the Wikipedia page for John Wilkes Booth (and many other places online) as showing the future assassin eyeing his target. But you won’t see that insert at the Ford’s Theatre museum anymore. To their credit, they identified that there wasn’t any evidence to support the hatless man as Booth and changed their display. I only wish I could get them to do the same regarding the incorrect knife they have on display as Booth’s.

I hope that this post outlines the misconceptions about John Wilkes Booth at Lincoln’s second inauguration. We know he was there and witnessed the event. There is no guarantee that he is present in any of the inaugural photos, however. The identification made by Frederick Hill Meserve is a theory, like anything else. In my eyes, it is a decent one. The man Meserve says is Booth looks like Booth to me. I wouldn’t bet my life on it, but it’s a harmless enough theory to support.

References:

Frederick Hill Meserve’s original identification of Booth in Life magazine

Twenty Days by Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt and Philip B. Kunhardt, Jr.

The Photographs of Abraham Lincoln by Frederick Hill Meserve and Carl Sandburg

Recent Comments