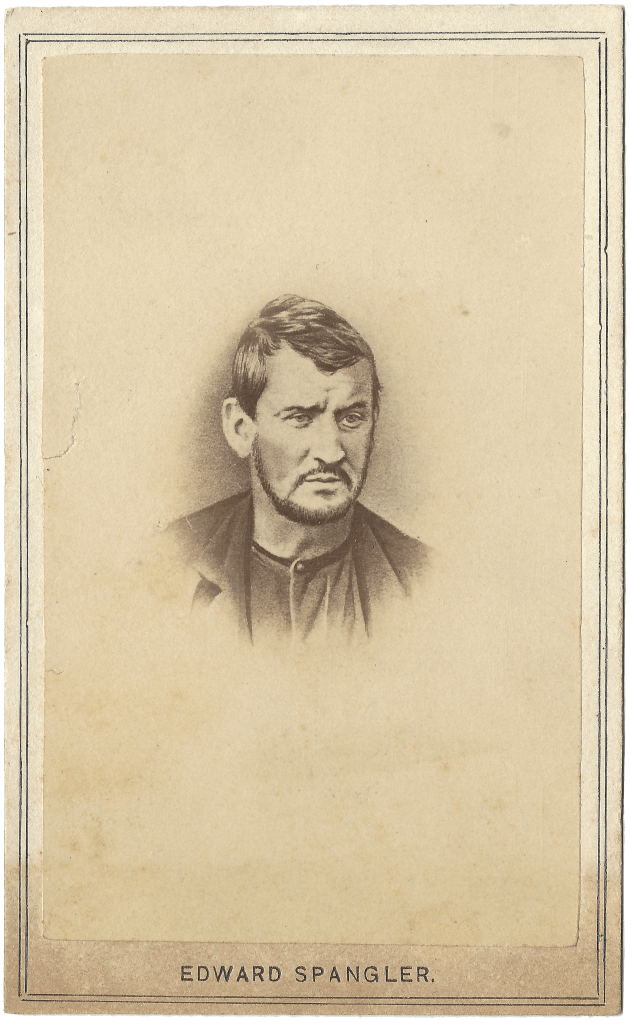

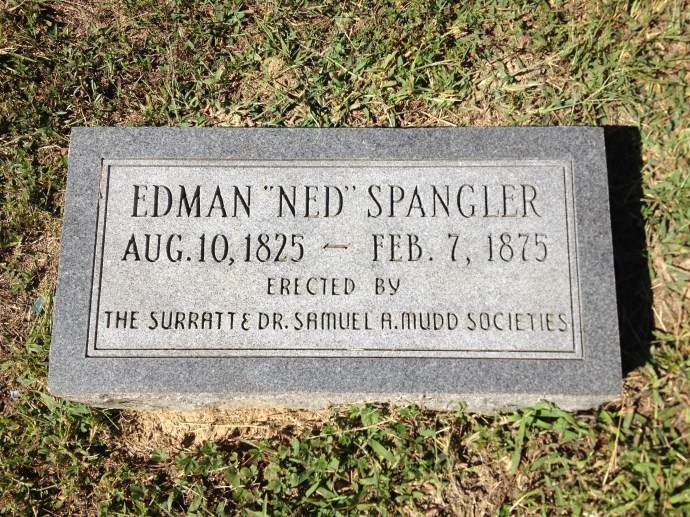

Today, February 7, 2025, is the 150th anniversary of the death of Edman Spangler. A carpenter and stagehand at Ford’s Theatre, Spangler was convicted of being a conspirator in John Wilkes Booth’s plot against Abraham Lincoln. Sentenced to six years of imprisonment at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, Spangler was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in 1869. After returning home, Spangler returned to working for John T. Ford at his theater in Baltimore. However, a fire gutted the Holliday Street Theater in 1873, leaving Spangler out of a job. He ended up traveling down to Charles County, Maryland, to the home of his former cellmate, Dr. Samuel Mudd. Though the two men had never met each other prior to their arrest and trial, they had bonded during their years together at Fort Jefferson. Dr. Mudd welcomed Spangler into his home with open arms and even gave him some acreage on the farm property for Spangler to work and live on. Spangler died at the age of 49 after contracting an illness in a heavy and cold rain. The Mudd family had their friend buried in a local cemetery, the original St. Peter’s Church Cemetery, which also held the grave of Mrs. Mudd’s father.

Of the nine Lincoln conspirators that were tried in 1865 and 1867, Edman Spangler is the one for which there is the least amount of evidence connecting him to the assassination. Spangler was mostly in the wrong place at the wrong time and was also unfortunate enough to be friendly with the wrong person: John Wilkes Booth. Upon arriving at the backstage door of Ford’s Theatre, Booth called for Spangler to hold his horse. Spangler quickly delegated the task to a less critical Ford’s Theatre employee before returning to his duties shifting scenes. After the shot rang out and the assassin ran out the backstage door, a confused Spangler was unsure what had occurred. When another stagehand suggested that it was Booth who had committed the crime, Spangler cautioned the man not to jump to conclusions or say anything that might slander an innocent man. When it was later firmly established that his friend, Booth, had committed the terrible deed, his words and actions came to be seen as conspiratorial. Investigators felt that Booth must have had an “inside man” at Ford’s Theatre in order to ensure his success, and so Spangler became that man in their eyes.

In reality, there is no conclusive evidence that Spangler knew anything of Booth’s plot against Lincoln. The two men were friendly and had a history dating back to when Spangler helped to construct the Booth family home of Tudor Hall in Bel Air. Spangler assisted Booth by constructing a stable for him in the alley behind the theater, and he was certainly pro-Confederate in his leanings. However, there is no strong evidence that Booth entrusted Spangler with the details of his plot. Instead, it appears that Booth felt bad for the trouble his actions brought to Spangler. After Booth was killed on April 26, 1865, his accomplice David Herold was taken into custody and transported up to Washington. During his integration by the authorities, Herold stated that Booth had told him during their escape that “There was a man at the theatre that held his horse that he was quite sorry for.” While Herold didn’t recall his name at the time, he recounted that “Booth said it [i.e. the act of holding the horse] might get him [Spangler] into difficulty.”

That act did, indeed, get Spangler into difficulty. Yet even the term of his jail sentence of six years demonstrates how poor the evidence was in trying to connect Spangler to the plot. All of the other conspirators tried alongside him were sentenced to death or life in prison, making Spangler’s punishment a “slap on the wrist” by comparison. However, as my recent documentary series on The Lincoln Conspirators at Fort Jefferson shows, life was incredibly difficult for Spangler and the other men sentenced to the Dry Tortugas.

In memory of the innocent Lincoln conspirator on the 150th anniversary of his death, here are three letters Edman Spangler wrote from prison during the time when Yellow Fever struck the fort. They were written to unknown friends of Spangler’s in Baltimore and then published in the newspapers. From other writing samples of Spangler’s, we know that he struggled with spelling and grammar. However, these three letters contain relatively few mistakes, implying that he may have been assisted in their writing by his cellmates or that perhaps his letters were cleaned up by the newspaper editors. Regardless, they give a brief peek into the life of Edman Spangler during the most terrifying portion of his imprisonment.

Fort Jefferson, Fla

Sept. 6, 1867

I am well at present, but don’t know how long it will last, for we have the yellow fever here, and there are two or three dying every day, and I am busy working in the carpenter’s shop, making coffins day and night, and I don’t know when my time will come. They don’t last more than a few hours. I will enclose a few moss pictures for you, and I will send you a barrel of coral, if I don’t get the yellow fever and die; but there are ten chances to one if I ever see you again. It is very desperate here. The doctor of the post is very sick with it, and there is no doctor here but Dr. Mudd, and he volunteered his services, and has made a good hit of it. We have lost no cases with him yet.

With love all,

Edman Spangler

Fort Jefferson, Florida

September 23, 1867

I have received the barrel of potatoes and am very thankful for them. We have drawn but a half bushel of potatoes from the government since the first of January. We have bought some at Key West, for which we paid seven and eight dollars per barrel. There are some seven of us in one mess; we do not eat with the other prisoners. We have the yellow fever here very bad. We had a doctor that came from Washington: he got it and died: his name was J. Sims Smith. He has a wife and two children. Dr. Mudd was in charge for a few days, and was very successful, and then they got a doctor from Key West; but Dr. Mudd is still in the hospital attending to the sick, and I am in the carpenter shop making coffins for those that die. While I am writing they have burned all the beds that belonged to every one that got sick, and all their clothing. We have a dreadful time of it here. There is no use of getting frightened at it; we must stand up and face the music.

Since writing the above, one of Dr. Smith’s children has died, Lieutenants Solam and Ohr, Major Stone’s wife and Michael O’Laughlin.

Fort Jefferson, Florida

Sept. 24

Poor Michael O’Laughlin, my friend and room-mate died at 7 o’clock yesterday of yellow fever, and during the 24 hours, seven others passed from life to eternity. The fever has assumed a more malignant type. There is but one officer for duty at the post, the others having died or now lying ill with the fever. Lieut. Gordon, taken two days ago, is now lying in a critical condition. From all I can learn, we have had 280 cases, out of which so far thirty have died. Some are even taken with it the second time, and from appearances, and from what the Doctor says, we shall always have it here – the thermometer never falling below 63 degrees. I have not been attacked yet, but may be at any moment, in which case I thought it best to forward to you and my family small mementoes, should I die of the fever. Arnold has had it, and has fully recovered, yet remains in a very weak condition. Something should be done, if possible, towards obtaining our removal from this den of pestilence and death to some more healthy place. Nearly all the late cases are of a very malignant type, scarcely any recovering.

Sources:

“Letter from Spangler,” New York Times, September 22, 1867, 3.

“Letters from the Dry Tortugas,” Baltimore Sun, October 11, 1867, 1.

Recent Comments