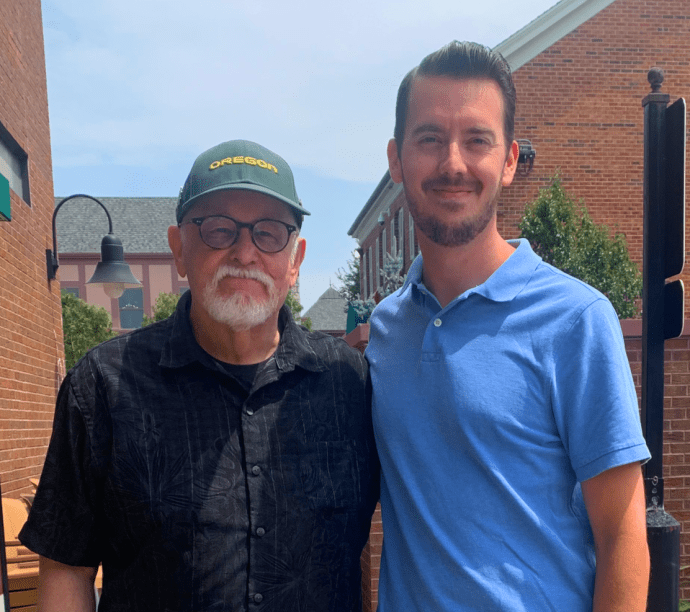

During my high school and college years, I had a growing interest in the Lincoln assassination. With the help of an online forum on the subject, I quickly found myself going deeper and deeper into this historical rabbit hole. While I had a friendly group of online acquaintances who shared this historical interest, I had never met any of them in person. At that time, I lived in Illinois and had only taken a single trip out east with my dad to visit D.C. and sites related to Lincoln’s death. Luckily for me, one of my new online friends was also a resident of Illinois and lived only about an hour and a half away. So, in November of 2010, he and I arranged to meet at a brunch place to “talk shop.” This is how I came to become friends with Steven G. Miller.

For those of you who watched my recent Booth exhumation trial reunion videos, Steve Miller should be a familiar name and face to you. Steve is a self-proclaimed “specialist” in the Lincoln assassination field. He has an intense interest in the members of the 16th New York Cavalry who tracked down and killed John Wilkes Booth. He has been researching and writing about the life of the main Lincoln Avenger, Sgt. Boston Corbett, for decades. There is no one on this planet with greater knowledge of the hunt for Booth than Mr. Miller. And, despite his claims of only being a specialist, Steve’s knowledge about many other aspects of the Lincoln assassination story is strong. Steve actually discovered an unpublished photograph of John Wilkes Booth and regularly delves into newspaper archives looking for new and interesting tidbits in this vast story of ours.

I was incredibly fortunate to have Steve as my guide into the world of the Lincoln assassination. He has amazing stories working with past greats of the field, and he was also incredibly generous with his research and his knowledge. I was constantly peppering him with questions in those early years, and he was always willing to dig into something for me. Our communications slowed down a bit after my move to Maryland, but around the time of my divorce and the pandemic in 2020, Steve and I started talking more often. Today, I speak to Mr. Miller on a weekly basis (if not more) and consider him a dear friend.

I write this narrative introduction not only to share my appreciation for Steve, but also to butter him up in hopes I can wrangle him into becoming an occasional contributor to LincolnConspirators.com. Steve has explored many interesting side stories that I think readers of this site would love. What follows is an article that Steve wrote concerning an intriguing newspaper article he came across a few months ago. I hope you all enjoy it, and I hope it’s the first of many articles on here from my mentor, Steve Miller.

Jeff. Davis’s Final Secret Mission.

By Steven G. Miller

Lake Villa, IL

Dave Taylor from LincolnConspirators.com and I often share historical goodies, those things that we have found in our research that interest or excite us. More times than not, our collaboration helps fill in gaps and answer questions that have stymied one (or both) of us.

Such it was, recently, when I found a long two-part article in the digital archives of the Washington Evening Star. It was the account by a former Confederate officer, identified only as “T.C.C” in the article, of a secret mission entrusted to hm by Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Secretary of State Judah Benjamin. The writer claimed that he was an invalid soldier who was in Richmond in early 1865 and that he was called to a meeting of those two officials, who were busy sorting through government files in preparation for the abandonment of Richmond.

He related that he was asked if he would carry a secret message through the blockade to Confederate representatives Mason and Slidell in England. He agreed and set out, he states, from Richmond on April 2 to head overland to Canada, where he could catch a ship across the Atlantic. The message he was given was written in cypher on “silk paper” and along with it was a draft for expenses on the funds held by the rebel commissioners in Montreal. They were “sewed up in the shank of a pair of boots.”

“T.C.C.” recounts that he left Richmond by train and continued mostly on foot northward. He crossed the Potomac at night and was taken in tow by rebel operatives. He made slow progress and was only in “T.B.” on April 10th. He was, he claimed, onboard a Washington-bound stagecoach when he was scooped up by the Yankee cavalry operating out of Chapel Point.

He identified himself to the soldiers as a former rebel officer who was bound for Canada with intentions of heading for Europe. They questioned him at length and searched him, but failed to find the secret stash. He was still in the guard house when the news of Lincoln’s assassination arrived a few days later.

Fearing for his life and realizing, “I am the object of suspicion,” he spent several anxious days and nights. Luckily for him, the secret in his boot remained safe. He was ordered to be sent to Washington, where his story could be checked out. He was taken on horseback and in a wagon and had several tense moments when crowds of angry citizens spotted him and asked whether he was one of the conspirators.

General Augur’s officers questioned him and, though they didn’t punch holes in his story, they sent him on to Carroll Prison. He was first put in solitary confinement, but he had outside connections and was thus able to obtain money to make his jail stay more comfortable. He was granted access to the “open room” and could communicate with other prisoners. He recounts being “pumped” for information by prison spies, whom he outsmarted, and then having encounters with several people involved tangentially in the assassination story.

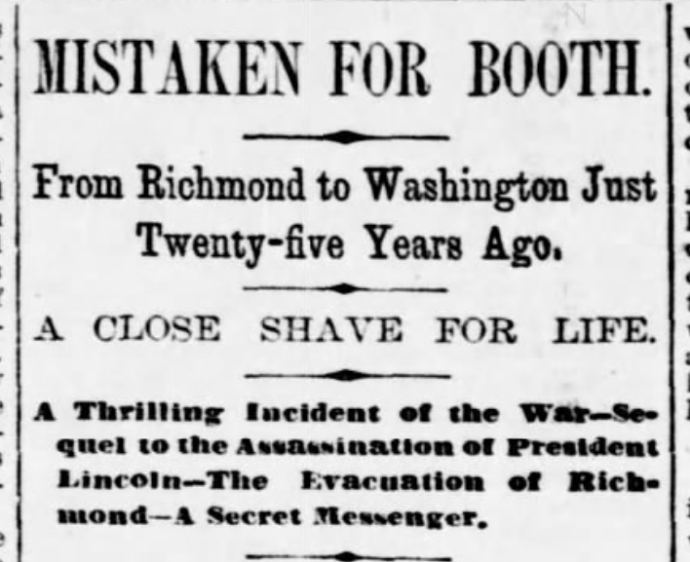

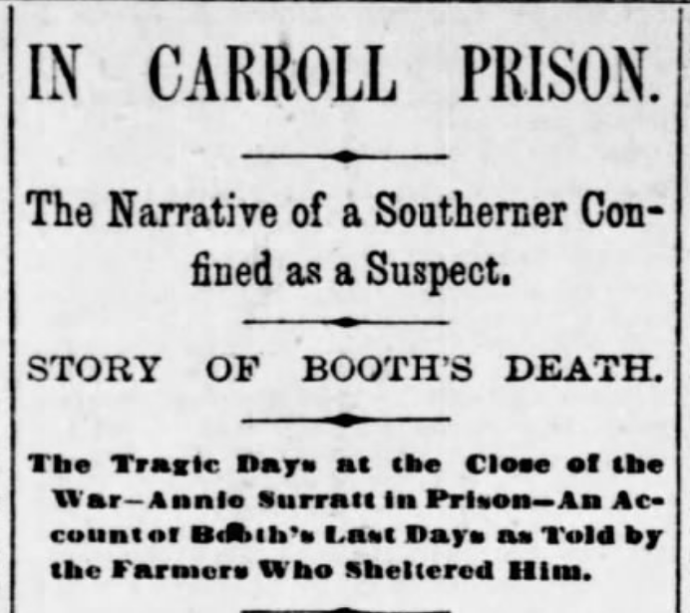

The two articles I found were:

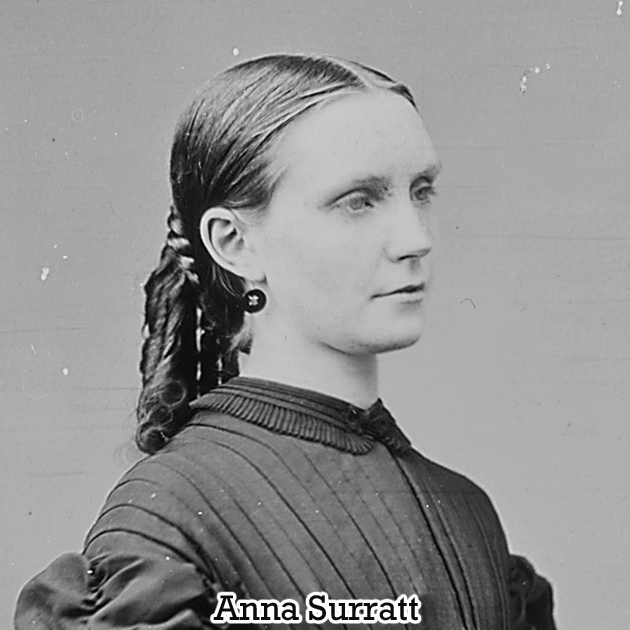

Dave and I decided to try to verify this account. What interested us especially was the story he told about meeting Annie Surratt in Carroll Prison. If true, it sheds new light on her ordeal and reactions while being held as a material witness.

My efforts to identify “T.C.C.” drew a blank, but Dave –ace researcher that he is – was able, we believe, to figure out who the author of these accounts was. He texted me saying: “Pretty sure the author of those articles is a Georgian named Theodore Cooke Cone. I found the name “T. C. Cone” in a list of Prisoners of War. It states he was arrested on April 10, 1865 in “T.B. Md” and he was released on May 9, 1865. Cone is also listed as being in the “Invalid Corps, CSA.”

As Dave said, “The service record for Theodore C. Cone shows he was retired from being a Captain with the 10th Georgia Infantry due to medical issues in Nov. of 1864 and was in Richmond at the time. While the article gives Jan. 1865, as the time of the author’s invalidity, it still seems to add up.”

Cone was the oldest son of Hon. Francis H. Cone (1797-1859), judge of the Georgia Superior Court and a state senator. The Cone family owned Ringgold, a sprawling 1,185-acre plantation which produced a variety of crops and was home to many slaves. Following in his father’s footsteps, Theodore became a lawyer and had a thriving practice. He became wealthy upon the death of the judge in 1859 and the sale of Ringgold.

When the Secession crisis flared up in 1860, T.C. Cone was an outspoken “fire-eater” who actively supported the CSA once it was established. In 1861, when the governor of Georgia failed to supply weapons for the local volunteer unit that Cone had helped raise, Cone wrote to Jefferson Davis personally asking for guns. It was granted.

The 10th Georgia was in many battles, including Gettysburg, and Cone was a popular captain of the regiment. As noted above, he was released from service in the latter part of 1864 due to unspecified medical issues. He retired to Richmond instead of returning to his home state. There, he came to the attention of a staffer in the Confederate White House and was invited to meet the chief executive and Secretary Benjamin.

Cone never made it to England, however, and his mission was scrapped after his stay in prison. In his Star articles, he recounts that he was in New York City a few months after his release from Yankee jail. As he recounted his exploits to a friend, the question arose about what happened to the message.

“That reminds me,” Cone said, “the dispatch is still in the shank of my boot. It is time I destroyed it.” He cut the boot open and saw that “the dispatch and check were in an excellent state of preservation.” He threw them onto the fire in the grate and commented as they went up in smoke: “That is one state secret that will never be divulged.”

Not only was Cone involved in this one last attempt by Davis to communicate with the agents in England, but he was also scooped up in the dragnet for the assassins of President Lincoln.

He tells of a prison meeting he had with Annie Surratt, the daughter of Mrs. Mary Surratt, who was then under arrest for conspiracy to kill President Lincoln.

Here’s what he wrote about this encounter:

“On one occasion an official of the prison put a slip of paper in my hands, which I found to be a “permit” to visit the ladies’ department of the prison. I, always suspecting that snares were being laid for my feet, said “I have not applied for this. There must be some mistake. I know no one there that I am aware of.” He replied: “A lady applied for it for you. She saw you walking in the yard yesterday and is a friend of yours.”

“On going up there I was met by a masculine-looking woman with an aggressive air, who introduced herself as Mrs. B—— of Baltimore, saying that she had met me once in Richmond the winter before. She explained that she had been to Baltimore to get medicines, which she had successfully done several times before, but had been captured on her last return—with three trunks, her cloak and apparel loaded with quinine. “This is another snare,” I thought, and this idea was confirmed to me when she at once invited me into a room, where several ladies were seated, saying: “I want you to see and talk to Annie Surratt. Poor thing, she is almost crazy,” and the next instant I was introduced to

ANNIE SURRATT

“I saw before me a slight girl of perhaps twenty years or past. She had very light blonde hair or it was more what I should call flaxen, with very light eyebrows and almost white eyelashes, very light blue eyes, and wearing at this time the pallor of death. Mrs. B— informed me that she had not then slept or taken food for eight days. On observing her a moment longer, I noticed that she quivered like a reed in a storm and that the pupils of her eyes were contracted to the size of a pin’s head, showing the intense nervous tension under which she labored. The conversation of twenty minutes which ensued between us I have neither the disposition nor the right to repeat. It is enough to say that her only concern was the life of her mother, whom she said she knew to be “as guiltless as an angel in heaven of the crimes of which she stood charged,” As I rose to go I saw lying on a table near us a copy of Harper’s Weekly with a picture of Booth’s flight from the rear of theater, Booth being on horseback. As she stood a moment near it, she nervously seized a pencil lying there, and, with hysterical suddenness of manner, hastily obliterated the face of the man. Having given all the little comfort possible under the circumstances I took my leave of the heart-broken girl. As a remarkable instance of the enormous extremes to which even the sanest minds ran in that fearful time of universal suspicion, I will state a simple fact.”

I don’t recall reading any comments about Annie Surratt in prison. And this new story about a final secret mission from Jeff Davis is new, too. The obvious take away from Cone’s story is that it was good that the Union authorities did not search him sufficiently enough to find the documents from Davis. It’s not hard to imagine what would have happened if Col. Baker had discovered that Annie Surratt – who was allowed to see her mother from time to time – was in unmonitored direct communication with an agent from the president of the CSA. It seems obvious that Cone and Annie Surratt would have been put in solitary confinement in the Old Capitol under close guard. The implication – unfounded according to Cone’s account—was that Davis was issuing orders directly to Mrs. Surratt in jail via his personal agent. This would have ended up in a charging indictment for Mrs. Surratt and for Davis. The conspiracy trial managers could never find a direct connection between Davis and any of the conspirators. It could have been argued in court that this was the smoking gun.

This apparently is the print of Booth on horseback that Annie Surratt defaced. Note: It actually comes from the May 13, 1865, issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, not Harper’s Weekly.

Recent Comments