The Ford’s Theatre Center for Education and Leadership opened on February 12th of this year. The building, adjacent to the Petersen House where Lincoln died, continues the message of Lincoln’s legacy after his death. The Center has four floors open to the public. The first floor is the lobby and gift shop while the second holds space for temporary exhibits. The third floor is deemed the “Legacy Gallery” which shows the many ways in which Lincoln has become ingrained in our culture and how his words affect us today. While very nice and good, as a person interested in the Lincoln assassination, it is the 4th floor, named the “Aftermath Gallery” that I wish to discuss.

Visitors exit the Petersen House and travel via elevator to the 4th floor of the Center and work their way down. On this floor you begin by viewing the turmoil that occurred on the morning of April 15th when the nation woke to the news of Lincoln’s death. There is a recreation of the train car that took Lincoln’s body back to Springfield as well as an interactive map of the route. Past this, are several wall displays recounting the manhunt for Booth and the imprisonment, trial, and execution of the conspirators:

Before approaching the stairs down to the next level, there is a recreation of the tobacco barn with audio and visual effects to show Booth’s last few moments before being shot.

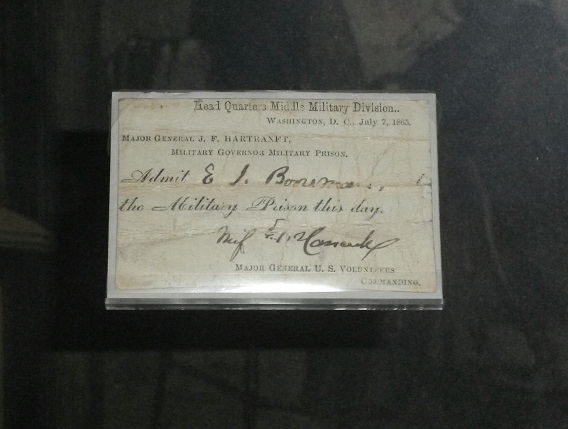

As always, it is the artifacts and relics of the assassination that draws my interest. They have a pass to witness the execution of the conspirators on July 7th, 1865:

A steering wheel from the USS Montauk:

The USS Montauk and the USS Saugus were ironclad monitors which housed the conspirators during the initial investigation and arrests. The Montauk held George Atzerodt, Edman Spangler, David Herold, John Wilkes Booth’s body, and Joao Celestino, an unrelated Portuguese sea captain.

The gallery also has a nice display of the sketches military commission member Lew Wallace drew of the conspirators during the trial:

The Center also has on display Lewis Powell’s saddle:

Powell used this saddle on the night he attacked Secretary of State William Seward. Powell biographer, Betty Ownsbey, was the first to see that this item was mislabeled as being owned by Booth (it was owned by George Atzerodt) and that it was improperly displayed. The stirrups were shown under the saddle flap instead of over them, which would make a very uncomfortable ride for the horse. After being made aware of the mistake, Ford’s has gladly fixed this and is now correctly displaying the beautiful saddle

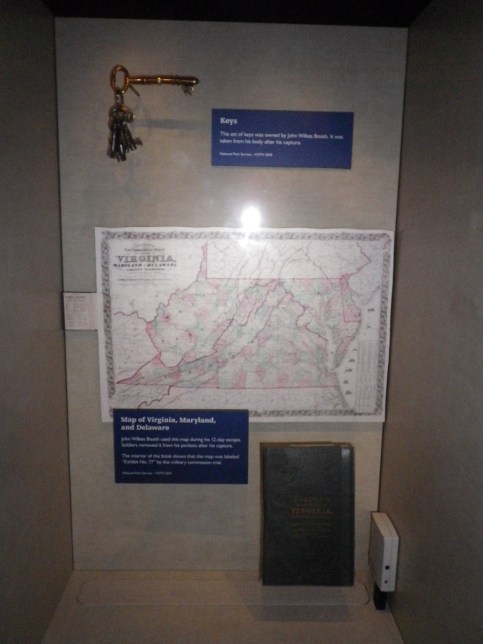

There is also an entire display case in the “Aftermath Gallery” with artifacts that I believe to be mislabeled:

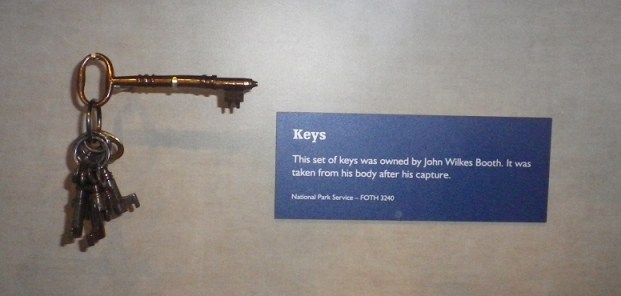

The display has two items, a set of keys and a map. The keys are labeled as, “being owned by John Wilkes Booth” and being, “taken from his body after his capture.”

I do not believe that this is the case. The War Department had these keys before they had even found John Wilkes Booth. An April 24th inventory list of evidence cites, “No. 9 Envelope containing silver pencil, and a bunch of keys belonging to David Herold.” These keys contained Davy’s key to his house and other places. On the morning of April 15th, Detectives James McDevitt, John Clarvoe, and John Waite, along with Lewis Weichmann, visited the home of Mrs. Herold. Here, they obtained two photographs of David Herold. They also recovered these keys and a silver pencil. According to a statement by Jane E. Herold, Davy, “…had to get home at 10 o’clock. If not he would be locked out. Always when he came he had a night key, but momma took it away from him…” While McDevitt and the others made mention of the photographs as they hoped it would increase their chances of getting some reward money, they didn’t mention the keys as they were not noteworthy. In addition, if you read through the statements of people at Garrett’s barn when Booth was cornered and killed, none of them ever mention keys being taken from Booth’s body. At the trials, individuals like Conger and Baker give very detailed lists of what they took off of Booth’s body, with no keys being mentioned. Regardless, these keys could not have come off of Booth’s body as the government had them two days before Booth and Davy were found.

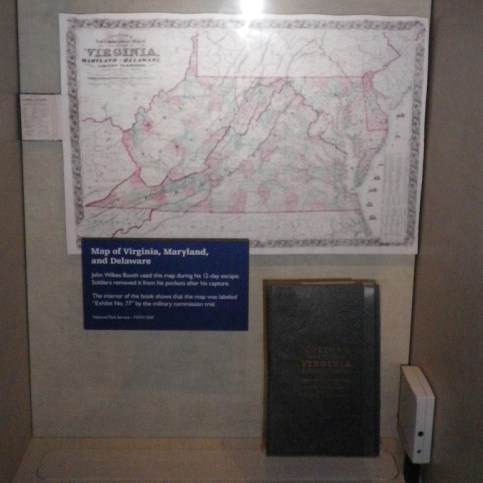

The other item in this display case is a map of Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware. The label for it states the following, “John Wilkes Booth used this map during his 12-day escape. Soldiers removed it from his pockets after his escape. The interior of the book shows that the map was labeled, ‘Exhibit No. 77’ by the military commission trial.”

I believe that this label is also wrong. Now it is true that Booth and Davy had a map with them during their escape. That map was taken off of Davy, not Booth, when he surrendered at Garrett’s barn. Unfortunately, this is not the map taken from Davy either. On June 3rd, Dr. Joseph H. Blanford, brother-in-law to Dr. Mudd, retook the stand at the conspiracy trial. The following is part of the interchange that occurred in Dr. Blandford’s testimony:

“Q. (Exhibiting a map to the witness.) Will you examine this map, and state to the Court whether the several localities that I have spoken of, and the roads, are properly marked upon it?

A. I think they are, as nearly as can be ascertained from this map; the roads not having been drawn upon it originally. The roads here, as drawn in ink, to the best of my knowledge, are the proper roads; and they would take those places in their route.

Q. Will you state whether you have examined that map before, and indicated the lines and points marked in ink upon it?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Show to the Court, on the map, where Surrattsville, Dr. Mudd’s house, and Pope’s Creek, are.

Assistant Judge Advocate Bingham. If he is going to do that, let him write them down at once on the map.

The witness. They are already written here. Dr. Mudd’s house, T. B. and other points on the road are correctly stated.

(The map referred to was offered in evidence without objection and is marked Exhibit No. 77.)”

To preclude the idea that the map shown to Dr. Blanford was the same one recovered from Davy, we have the following testimony from Everton Conger:

“Q. What articles did you take from Herold? Anything?

A. A little piece of a map of the State of Virginia, and a part of the Chesapeake Bay on it.

Q. Do you remember whether that map embraced the region of country where they were?

A. It did. It embraced that region of country known in Virginia as the “Northern Neck.”

Q. Was it a map prepared in pencil?

A. No, sir.

Q. Was it a regular map?

A. Part of an old school map; a map that had originally been five or six inches square.

Q. (Exhibiting a map.) Is that it?

A. Yes, sir: that is it.

Q. That embraces the region of country in which they were captured?

A. Yes, sir. That is the only property I found on Herold.

Q. Look at this pocket compass. (Exhibiting a pocket compass.)

A. That was taken from Booth’s pocket, just as it is now, with the candle grease on it and all.

(The map and compass were offered in evidence without objection, and are marked Exhibit No. 38.)”

So Davy’s map, along with Booth’s compass, was entered into evidence as Exhibit #38. Therefore, the map on display at Ford’s, marked as Exhibit #77, was not recovered from either Booth or Herold at Garrett’s. Instead this map was used by Thomas Ewing during his defense of Dr. Mudd.

Ultimately, while the Ford’s Theatre Center for Education and Leadership has wonderful potential, I personally would care to see more space devoted to their true role in history, Lincoln’s assassination. I understand that Ford’s has a fine line to walk in educating the public about Lincoln’s assassination, while not supporting the act. Their big museum does this by presenting Lincoln’s entire term of office inclduign the assassination. While this affords less space towards assassination related things, it also allows them to operate without appearing biased. In my opinion though, people come to Ford’s because they want to learn about Lincoln’s death. While a sad time in our history, I would prefer more attention in this area. Regardless, as a center for education, it is Ford’s duty to present history as accurately as possible. I hope that these artifacts will be looked into further.

References:

A Peek Inside the Walls: 13 Days Aboard the Monitors by John E. Elliott and Barry M. Cauchon

The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence by William C. Edwards and Edward Steers, Jr.

Recent Comments