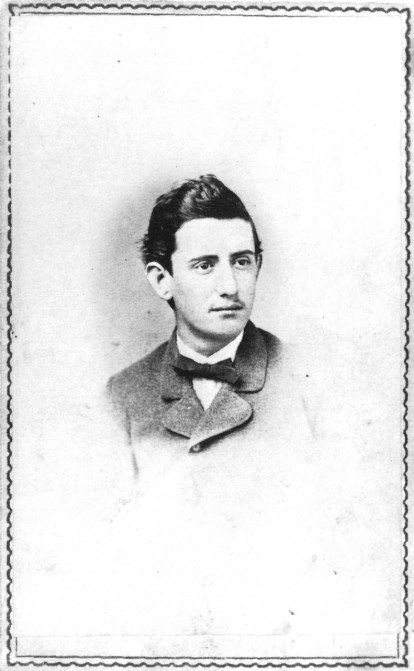

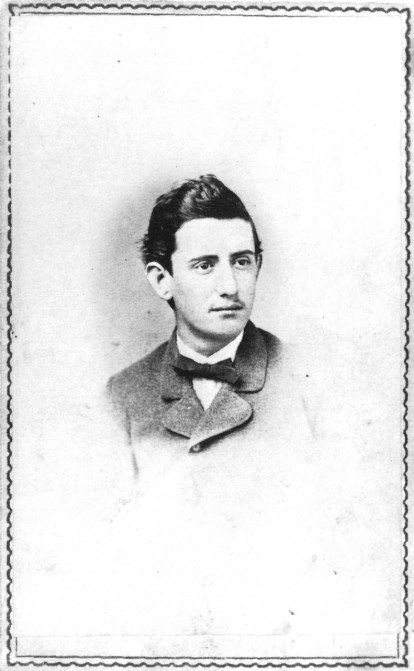

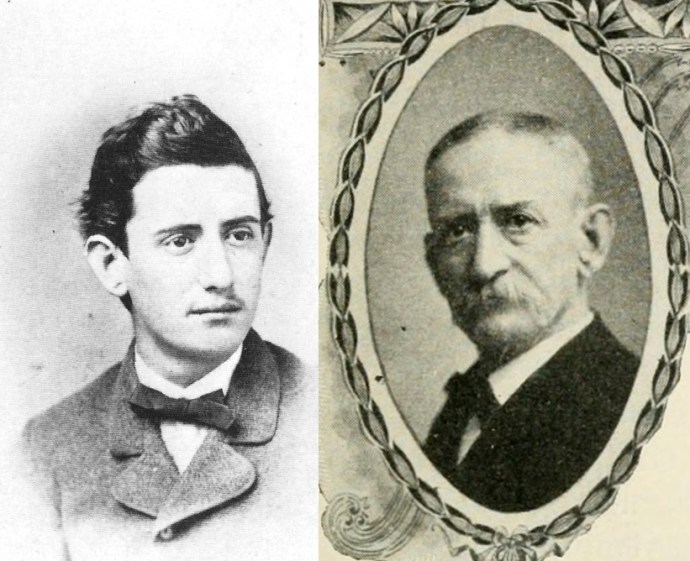

Yesterday morning, friend and frequent commenter on the site, Carolyn Mitchell, posted a new picture to the Spirits of Tudor Hall Facebook page. The image came from the book John Wilkes Booth Himself by Richard and Kellie Gutman. In this 1979 publication limited to just 1,000 books, the Gutmans compiled all the images of John Wilkes Booth that were known at the time. Their first one, labeled Gutman #1, is as follows:

Gutman #1

This image is captioned in John Wilkes Booth Himself with the following: “The earliest known photograph of John Wilkes Booth is a head and shoulders vignette, depicting him at age 18. One copy exists as a carte de visite done by Mansfield’s City Gallery, St. Louis, Missouri. In all likelihood, this is not the original photographer or photograph. John Wilkes Booth turned 18 on May 10, 1856-and that year is a bit early for a carte de visite in the United States. This may have been copied from another form of photograph (daguerreotype, ambrotype or tintype) or a larger paper print. In any event, copies of this picture are very rare. It has been published only one time, in Album of the Lincoln Murder (Harrisburg, PA.: Stackpole Books, 1965).”

Armed with this information, Carolyn posted the photograph like so many other rare and unique views of the Booth family she has come across.

Very quickly though, people started to express their doubts that this was a picture of Booth. Some said it could be of one of the other Booth brothers like Edwin or Joseph. I long ago questioned the identity of the young man in this particular photo, too. At the time of writing this, there were 15 responses to this photo on the Facebook page. After receiving an email from a colleague trying to remember a previous discussion regarding this photo, I decided to post here about it.

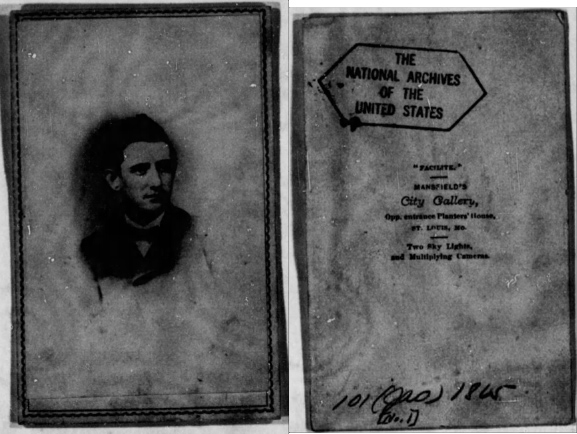

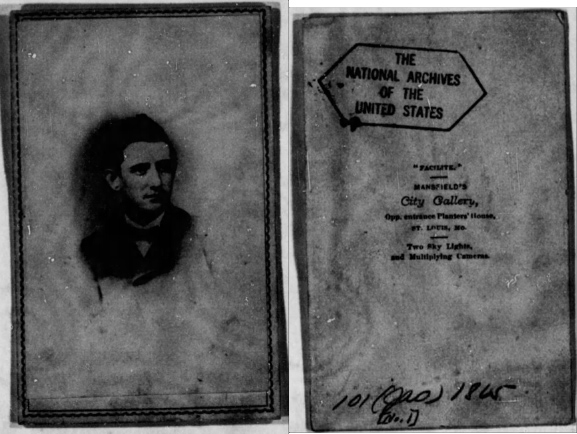

As far as I know, part of the description from the Gutmans is correct in that there is only one copy of this carte-de-visite known to exist. It is in the National Archives in their Lincoln Assassination Suspects file. Here is the microfilmed quality version of this CDV:

The CDV itself was found among Booth’s papers and files in the National Hotel after the assassination. It was deemed not relevant to the investigation but still retained in the government’s files. This probably explains the Gutman’s desire to include this picture in their collection of Booth photos. It was found with his things, does not bear any writing precluding it from being Booth, and has some similarities to the young tragedian turned assassin. Stating it is of a young Booth makes it easier to ignore some of the discrepancies in appearance.

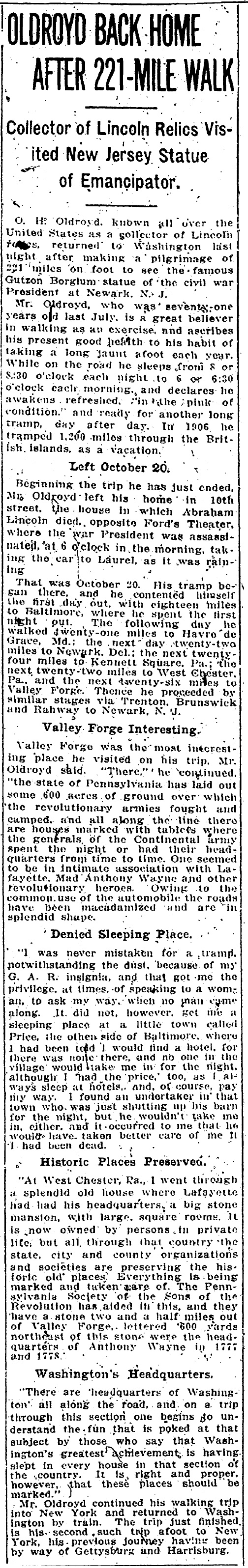

Not everyone, however took the identification by the Gutmans at face value on this one. In the book, The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence by William Edwards and Edward Steers, Jr., and in Steers’ The Lincoln Assassination Encyclopedia, this photograph is identifed as being Benedict “Ben” DeBar. Ben Debar was a theatre owner and actor. Junius Brutus Booth, Jr., JWB’s brother, married Ben’s sister, Clementine DeBar and they had a daughter together Blanche. June abandoned Clementine and Blanche, running off to California with a prostitue named Harriet Mace. Ben filed for a divorce on behalf of his sister and adopted Blanche as his own. John Wilkes assumedly still cared for his niece, as in his papers at the National, there is a letter from Ben DeBar extolling young Blanche’s early success as an actress. Attaching newspaper clippings and a playbill bearing the name “Blanche DeBar”, Ben brags to JWB, “I have sent June a bill to prove to him I have no wish that the girl should have any other than my name.”

The reason Steers and Edwards claim that this image, Gutman #1, is of Ben DeBar is because this image is microfilmed right alongside of the materials from Ben DeBar. Sandwiched right next to a newspaper clipping of Blanche’s success and a playbill announcing her performance in the comedy “Love Chase”, is this image. While the letter from Ben does not mention a photograph, its placement with the other materials seems to point that is from him.

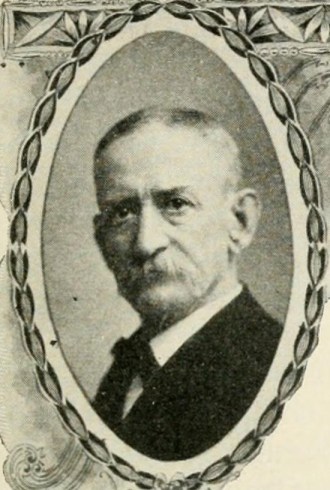

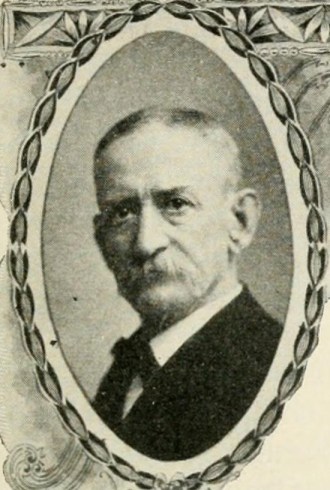

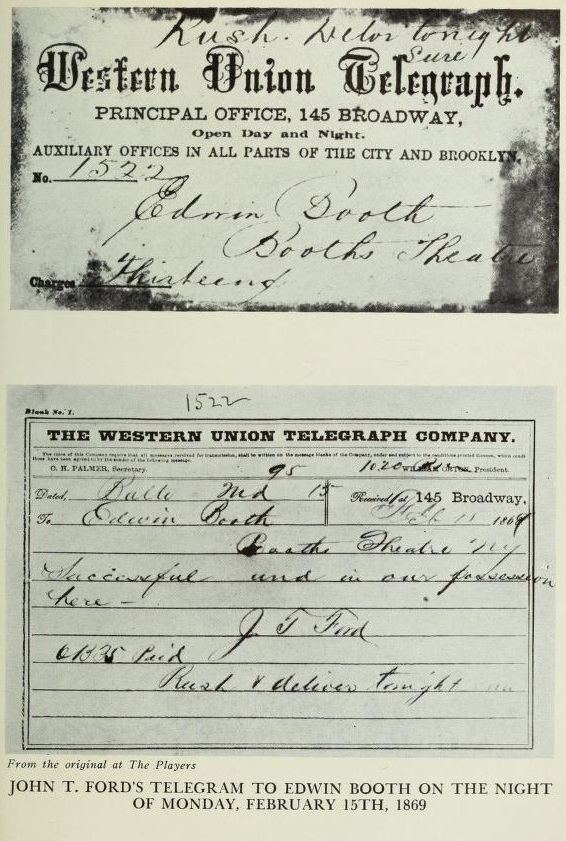

The problem is, however, that Ben DeBar was quite a bit older than the young lad in the picture. DeBar was born in 1821 and at the time of his writing in March of 1865 would have made him about 44 years old. Here’s a picture of Ben Debar taken around 1870 for comparison:

Ben DeBar

So while Steers and Edwards’ theory that Gutman #1 is Ben DeBar makes sense in the context of the image’s placement in the microfilmed files, the difference in ages and appearances makes it as unlikely as the photograph being of Booth.

Thus far, the most logical and probable explanation of who this individual is comes from the authors John Rhodehamel and Louise Taper who edited the book, “Right or Wrong, God Judge Me”: The Writing of John Wilkes Booth. They put forward that the man on this CDV was a young clerk working for General Grant’s office named Richard Marshall Johnson.

From Booth’s papers at the National we find that he did have a letter from Richard M. Johnson. Dated February 18th, 1865, Johnson writes in part, “I may be vain in presuming that our brief Memphis acquaintance has made us friends, but on my part it has…” Johnson recounts their initial meeting during which Johnson was drinking away his sorrows over the death of a friend. Booth befriended the young Union officer and evidently made quite the impression on him. Johnson asks Booth about his oil ventures and gives him the “riot act” for not acting this season. “You have too fine a reputation in this part of the country to let a winter pass away without giving us a call,” Johnson explains. The remaining part of the letter is of a request Johnson has of Booth:

“By the way, send me another of your photographs with your autograph on it. The one you sent me from New Orleans was disposed of rather strangely. A young lady of rare accomplishments and talent asked me for it. I refused the gift. She insisted and I proposed to get her a fine picture of you, but she wanted the one with your autograph. She has seen you frequently and was deteremined to have it. After much persuasion, I concluded to let her have it intending to write you for another. I gave it to her with the promise that when you visited this city I would take you to call on her. Today she sleeps in Bellefontaine Cemetery having died shortly after I gave her the picture. When I visit her family and see her album I see the name of J. Wilkes Booth written at the bottom of your photograph and think of the unfulfilled promise that she should know you. Your picture will always remain in the album as the touch she gave it in placing it there is now considered sacred. She was a woman of rare and beautiful excellence.”

While, as you can see, there is much talk in this letter of Booth’s photograph, Johnson never mentions sending one of himself to Booth. The evidence for that lies in a letter from Booth to Johnson that is housed at the Huntington Library. In the portion of letter above, Johnson mentions the photograph Booth sent him, “from New Orleans”. The letter from Booth to Edward Johnson is dated almost a year before the above letter on March 28th, of 1864 and states the following:

“Dear Johnson

Yours of the 12th; recd:. I am glad to find that you have not forgotten me, and hope I may ever live in your generous remembrance. I enclose in this a picture of myself, better (I think) than the one I gave you.

This of you I will ever keep among my very few and chosen friends. Excuse the shortness of this, am in haste. I am your’s

J. Wilkes Booth”

It is in this letter that Booth attached a photograph of himself – the same one that Richard Johnson later gave to the lady mentioned before.

The most interesting thing about this letter from the Huntington Library however, is the second paragraph which starts, “This of you”. Booth is speaking of his receipt of a picture from Richard Johnson. This, according to Rhodehamel and Taper, is the photograph found in Booth’s papers at the National Hotel.

According to his newspaper obituary, upon his in 1922 Richard Marshall Johnson was, “about 80” years old. This would put his year of birth about 1842, making him around 22 years old when he was corresponding with Booth in 1864 and 1865. This age range better matches the age of the young man in the photograph more than a 44 year old Ben DeBar does.

The paper evidence is strong for this picture to be of Richard M. Johnson. We know the following facts: Booth corresponded with Johnson and sent him photographs of himself. In turn, Booth received a photograph from Johnson in 1864. Booth had a more recent letter from Johnson in his papers when he assassinated Lincoln in 1865. Richard Johnson’s age during the time of his interactions with Booth match the apparent age of the man in the photograph. Based on this documentary evidence alone, I’m confident this picture is of Richard M. Johnson. But I’m not through yet.

Richard Johnson had an interesting life as this short bio will demonstrate:

“RICHARD M. JOHNSON was born in Illinois in the city of Belleville. He received his early education in McKendree College. Coming to St. Louis in 1858, he read law in the office of his brother, Governor [Charles P.] Johnson. In 1861 he was appointed a clerk in the Postoffice Department, and in 1862 was tendered a position as chief corresponding clerk in General Grant’s headquarters, under Quartermaster Colonel Chas. A. Reynolds. In 1865 he was appointed Superintendent of the State Tobacco Warehouse by Governor Fletcher. He was married to Miss Annie Blow, daughter of Taylor Blow of St. Louis, in 1866. Appointed by General Grant in 1867 as Post Trader at Fort Dodge, Kan., and in 1869 he accepted an appointment tendered him by General Grant as Consul to Han Kow, China, which office he held with credit for eight years. Two of Colonel Johnson’s children were born in China. He returned to the United States and resumed the practice of law in 1877. He was elected Assistant Prosecuting Attorney in 1894, and was again elected in 1898, and while he has always been active in politics as a Republican, he numbers among his friends, regardless of political affiliations, as many Democrats as Republicans.”

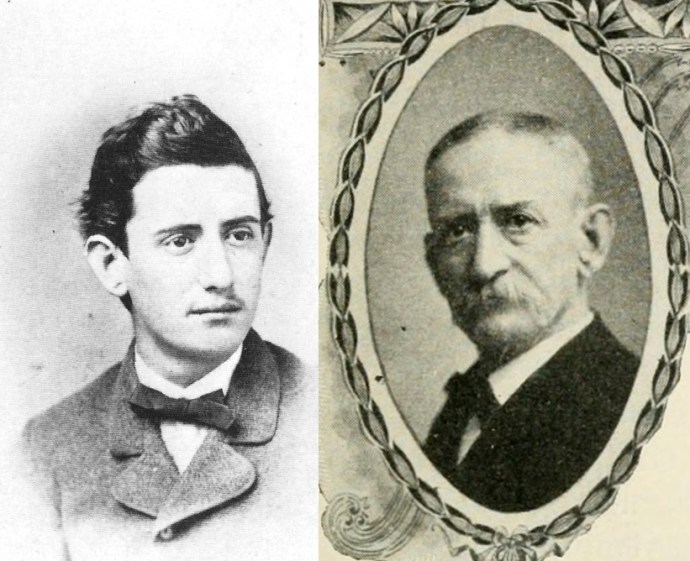

In 1904, Johnson provided a chapter for the book, “Reminiscences by Personal Friends of Gen. U. S. Grant” recounting his friendship and experiences with General Grant. His stories of Grant are very interesting ones and can be read in full here. In addition to the biography from above, the book also features a picture of Richard M. Johnson:

Richard M. Johnson

We all know photographs are subjective to the viewer. The Gutmans wanted this picture of a young man to be Booth and so they saw Booth in it. It could just be that I want this photo to be of Johnson because there is so much paper evidence supporting it, but I say these images show the same man, 40 years apart.

As far as Gutman #1 is concerned, I support Rhodehamel and Taper and say it is Richard Marshall Johnson.

References:

The Evidence by Edwards and Steers

John Wilkes Booth Himself by Richard and Kellie Gutman

“Right or Wrong, God Judge Me” by Rhodehamel and Taper

Reminiscences by Personal Friends of Gen. U. S. Grant

Fold3.com

Note: There may be more images of Richard Johnson for compariosn contained in the Missouri History Museum. They have a collection of diaries and scrapbooks attributed to R. M. Johnson.

Note: R. M. Johnson is buried in the same cemetery as the lady who wanted Booth’s photograph, Bellafontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

Thanks for the great topic starter, Carolyn!

Recent Comments