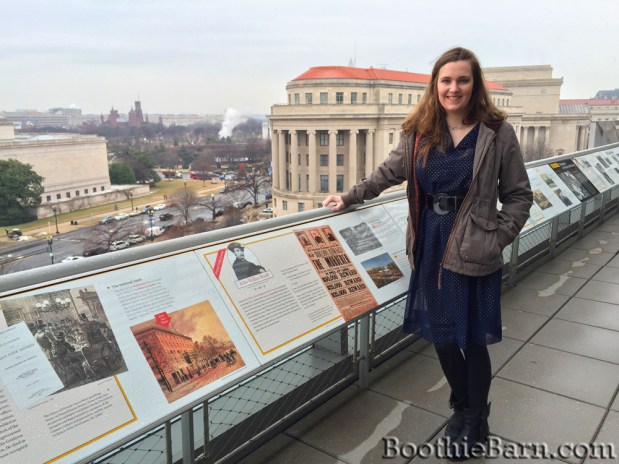

This is the second of two posts utilizing content gleaned from the diaries of Julia Ann Wilbur, a relief worker who lived in Alexandria, Virginia and Washington, D.C. during the Civil War. For biographical information on Julia Wilbur, as well as information regarding her diaries please read the first post titled, Julia Wilbur and the Mourning of Lincoln.

Witness to History: Julia Wilbur and the Saga of the Lincoln Assassination Conspirators

When Abraham Lincoln’s assassination occurred on April 14, 1865, Julia Wilbur understood the impact it would have on the history of our country. When not working to provide relief to the thousand of newly freed African Americans residing in Alexandria and Washington, D.C., Julia Wilbur was a student of history. She traveled far and wide to visit places of historical importance, relished exploring the old burial grounds of a city, and found instances to mingle with those who were shaping her times. Therefore, she not only took the time to be a part of the mourning events for Abraham Lincoln, but she also went out of her way to document and even involve herself in the saga of the Lincoln assassination conspirators. The following are excerpts from Julia Wilbur’s diaries detailing her interactions with the assassination’s aftermath.

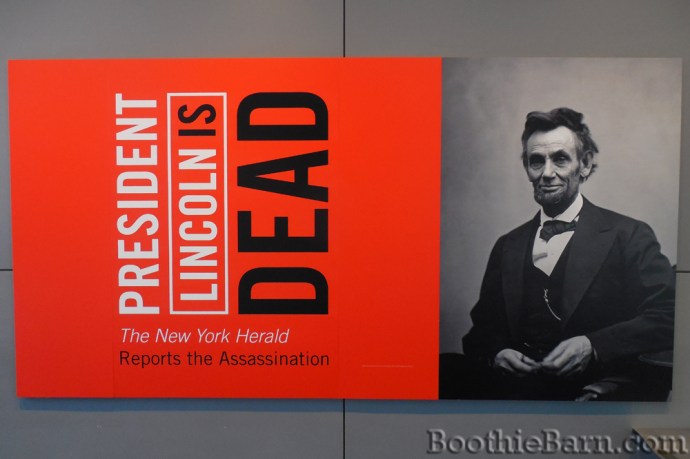

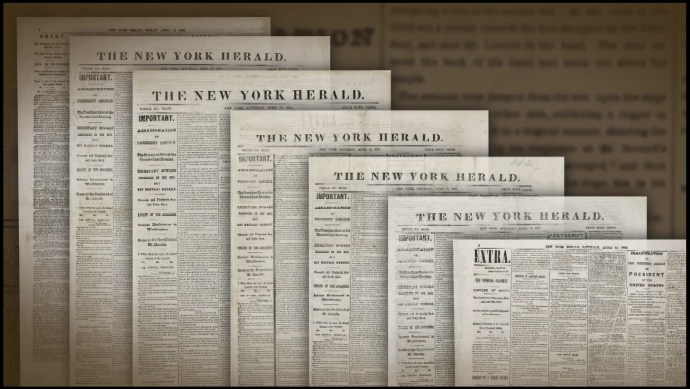

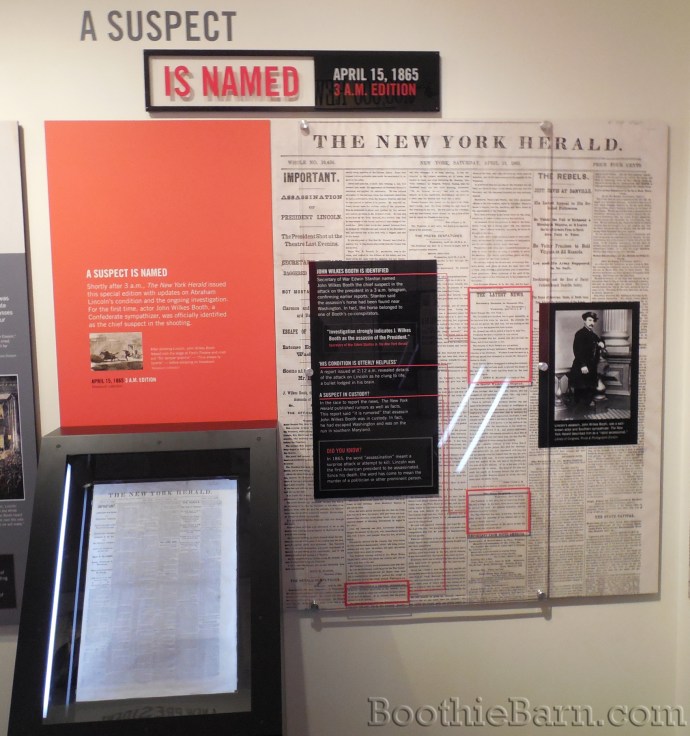

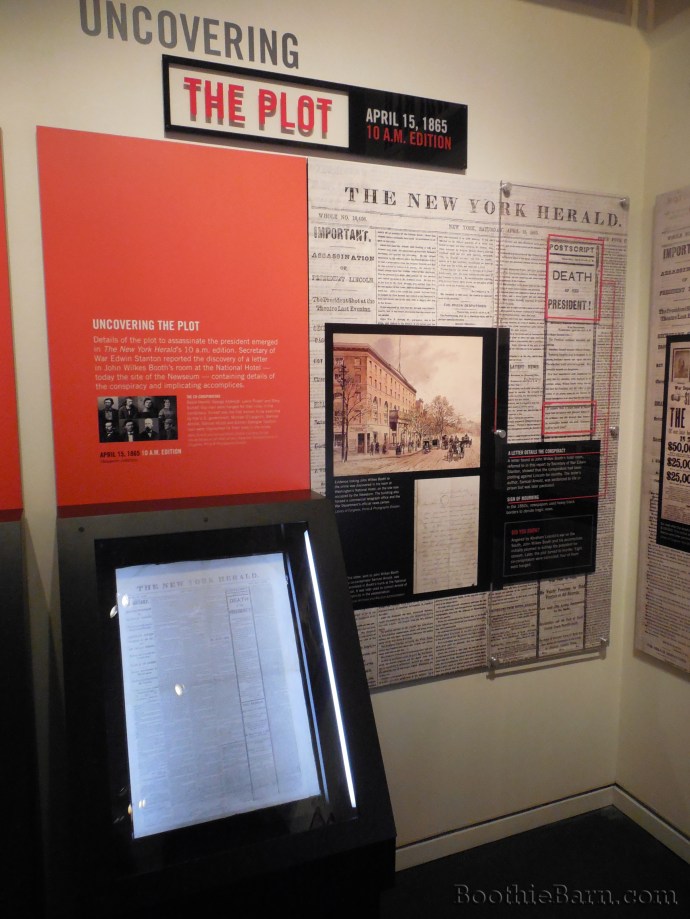

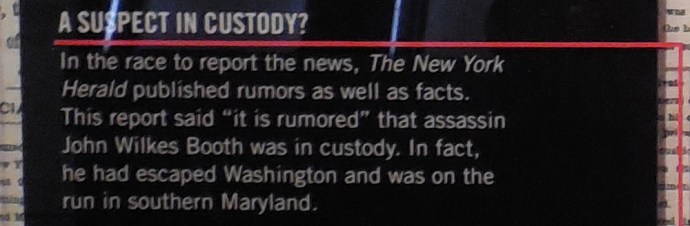

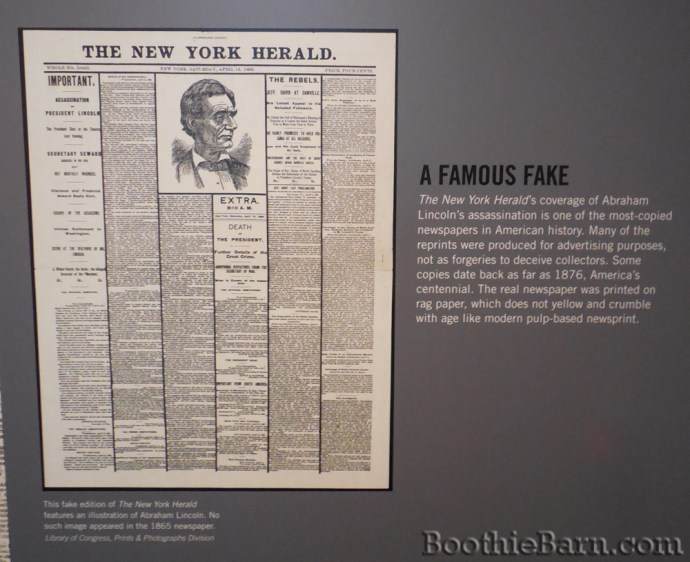

Reporting the News

Like many citizens around the country, Ms. Wilbur took to her diary to report the latest news about the hunt for Booth and his assassins. Sometimes the news was good. Other times, Ms. Wilbur reported on the gossip that was on the lips of everyone in Washington.

April 15, 1865:

“President Lincoln is dead! Assassinated last night at the theater shot in the head by a person on the stage. The president lingered till 7 this A.M. so all hope is over. And Secretary Seward had his throat cut in bed in his own house, but he was alive at the last despatch. It is said an attempt was made on Sec. Stanton but he escaped. Many rumors are afloat, but the above is certain.

…Evening. Sec. Seward is comfortable, & may recover, his son Frederick is in a very critical condition, his son Clarence has only flesh wounds & is able to be about the house. There is a report that Boothe has been taken; that his horse threw him on 7th st. & he was taken into a house.— There is no doubt that it was intended to murder the President, the Vice Pres. all the members of the cabinet and Gen. Grant. & that the managers of the theater knew of it.”

April 16, 1865:

“Two Miss Ford’s were at the Theater at the time of the murder.”

[Note: These Miss Ford’s appear to be friends of Ms. Wilbur’s and unaffiliated with the Fords who owned Ford’s Theatre]

April 17, 1865:

“About noon we saw people going towards G. on the run. & we were told that two men had been found in a cellar dressed in women’s clothes. & it was thought they were the murderers, Miss H. & I walked up that way. They are probably deserters. We met them under guard; they were guilty looking fellows.

…We passed Seward’s House. A guard is placed all around it. & on the walk we were not allowed to go between the guard & the house. He was not told of the President’s death until yesterday. He seems to be improving. No news in particular. No trace of the murderers.”

“Mr. Seward is no worse & Mr. F. Seward is improving.”

April 19, 1865:

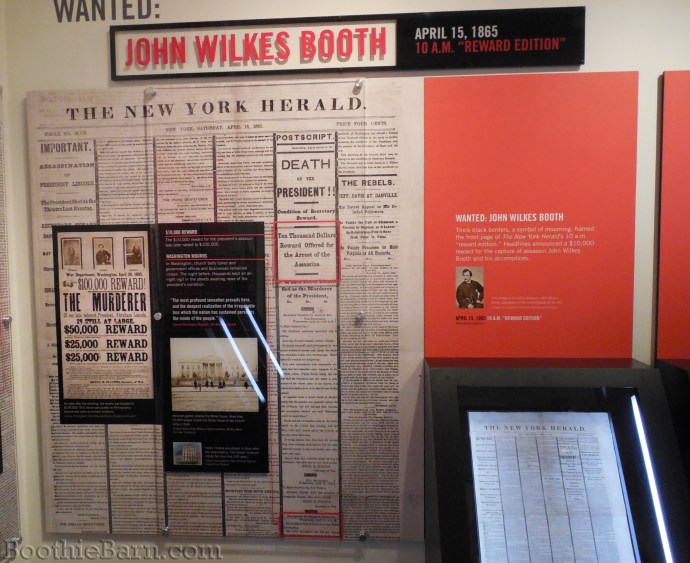

“When Frances got ready about 12 M. we went out. (all about are posted notices, “$20,000 reward for the apprehension of the Murderer of the President.”)”

April 20, 1865:

“Numbers of persons have been arrested. but Booth has not been taken yet. Ford & others of the Theater have been arrested. The Theater is guarded or it would be torn down. If Booth is found & taken I think he will be torn to pieces. The feeling of vengeance is deep & settled.”

April 21, 1865:

“I went around by Ford’s Theater today. It is guarded by soldiers, or it wd. be torn down. There is great feeling against all concerned in it.— Mr. Peterson’s House opposite where the President died is an inferior 2 storybrick,—but the room in which he died will be kept sacred by the family. A number of persons have been arrested & there are many rumors; but Booth has not been taken yet.— Mr. Seward & son remain about the same.”

April 26, 1865:

“Report that Booth is taken.”

Learning of Booth’s Death from an Eyewitness

One of the more remarkable things in Ms. Wilbur’s diary is how she recounts the details of Booth’s capture and death. On April 27th she is able to give specifics of Booth’s death when such details did appear in papers until the next day. The reason for this is because Ms. Wilbur was able to hear the story firsthand from one of the soldiers of the 16th New York Cavalry, Emory Parady.

April 27, 1865:

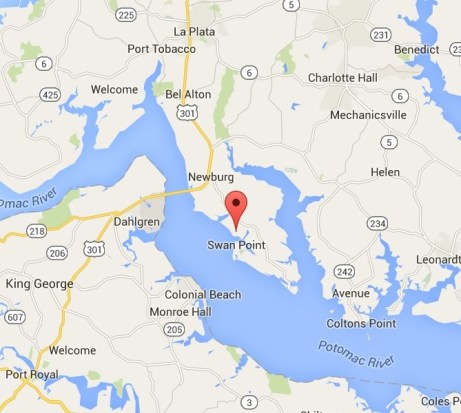

“Booth was taken yesterday morning at 3 o clock, 3 miles from Port Royal on the Rappac., in a barn, by 25 of 16th. N.Y. Cav. & a few detectives. He was armed with 2 revolvers & 2 bowie knives & a carbine 7 shooter, all loaded. Harrold, an accomplice was with him. Neither wd. surrender until the barn was fired. Then Harrold gave himself up. & when Booth was about to fire at some of the party, he was shot in the head by Sargt. B. Corbett, & lived 2 ½ hrs. afterwards. He was sewed up in a blanket & brought up from Belle Plain to Navy Yd. in a boat this A.M. One of the capturers, Paredy, was here this P.M. & told us all about it.”

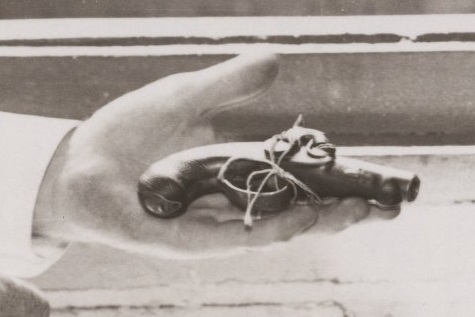

Collecting Relics

Julia Wilbur was fond of acquiring relics and would occasionally display her collection to visiting friends. The events of April 14th, motivated Ms. Wilbur to acquire some relics of the tragic event.

April 20, 1865:

“I purchased several pictures of the President, also Seward’s.

…Miss Josephine Slade gave me a piece of a white rosette worn by one of the pallbearers. Then Mrs. C. & I went to Harvey’s where the coffin was made. & obtained a piece of the black cloth with wh. the coffin was covered & pieces of the trimming. The gentleman who was at work upon the case for the coffin was very obliging & kind. This case is of black walnut, lined with black cloth, & a row of fringe around the top inside, I have also a piece of this box.”

April 21, 1865:

“Called on Mrs. Coleman. Then we went to Mr. Alexander’s & got some pieces of the cloth which covered the funeral Car. Then we saw an artist taking a Photograph of the car. which stood near the Coach Factory where it was made. We went there & Mrs. C. took of pieces of the cloth & alpaca. & a young man told us the Car would be broken up to day & he would save us a piece.

“…Then I went out again & obtained a board from the Funeral Car, which a workman was taking to pieces. & also some of the velvet of the covering. I intend to have this board made into a handsome box. & will make a pin cushion of the velvet.”

April 22, 1865:

“Went to see Mrs. Coleman. she gave me some of the hair of President Lincoln.”

May 2, 1865 (in Philadelphia):

“In all the shops are pictures of the President, & there are some of Booth.”

October 12, 1865:

“Called at Ford’s Theater. got relic.”

October 18, 1865:

“Then Mrs. B. went with me to Ford’s Theater & we each obtained from Mr. Kinney who has charge of the building, a piece of the Presidents Box. The wood work where his knees rested when he was shot.”

A Visit to Richmond

Ms. Wilbur temporarily departed Washington in mid May of 1865. During that time she traveled to Richmond, with side trips to Petersburg and Appomattox, to provide relief work for the newly freed African Americans. Diary entries during her time in Richmond lament the poor living conditions of the black citizens and also discuss her own experiences in the city. One of my favorite anecdotes from that period is Ms. Wilbur’s recounting having tea with a family of free African Americans.

May 19, 1865:

“Took tea by invitation at Mr. Forrester’s. Quite a company. We drank from Jeff. Davis’s tea cups, eat with his knives & forks & eat strawberries & ice cream from his china saucers— I sat in the porch & looked at Jeff’s house not many rods distant, & tried to realize that I was in Richmond— The morning of the evacuation people fled & left their houses open. goods were scattered about the street, & Jeff’s servants gave this china to Mr. Forrester’s boys. That morning must have been one long to be remembered by those who were there. All night long there was commotion in the streets. Jeff. & his crew were getting away with their plunder.”

“Thought I might as well see some thing of this important trial”

Ms. Wilbur returned to Washington, D.C. in mid-June. Once back home, she quickly resumed her habit of engrossing herself in the historical proceedings happening around her. In June of 1865, such historical proceedings could only be the trial of the Lincoln conspirators. Before attending the trial however, Ms. Wilbur first visited the conspirators’ former site of incarceration.

June 17, 1865:

“In P.M. went to Navy Yard. Went on to the Saugus & the Montauk.

…The Saugus weighs 10 hundred & 30 tons, draws 13 ft. water & its huge revolving turret contains 2 guns wh. carry balls of 470 lbs. It is 150 ft. in length, pointed fore & aft & its 83 deck & sides plated with iron. The turret, pilot house— smokestack & hatchways are all that appear on deck & in an engagement not a man is visible. It has been struck with heavy balls & deep indentations have been made on the sides of the turret. Once a heavy Dahlgren gunboat during an engagement, The Saugus did service at Fort Fisher.— There are 13 engines in this vessel.

We went below & saw the wonders of the interior. Booth’s associates were confined on this vessel for a time. Booth’s body was placed on the Montauk before it was mysteriously disposed of.”

Then, on June 19th, Julia Wilbur attended the trial of the conspirators:

“At 8 went for Mrs. Colman & got note of introduction to Judge Holt from Judge Day & proceeded to the Penitentiary.

Thought I might as well see some thing of this important trial.

Mr. Clampitt read argument against Jurisdiction of Court by Reverdy Johnson.

It was very hot there. Mrs. Suratt was sick & was allowed to leave the room & then they adjourned till 2, & we left. Mrs. S. wore a veil over her face & also held a fan before it all the while.

Harold’s sisters (4) were in the room. The prisoners excepting Mrs. S. & O’Laughlin appeared quite unconcerned. They are all evidently of a low type of humanity. Great contrast to the fine, noble looking men that compose the court.”

Ms. Wilbur’s diary entry concerning the courtroom is valuable not only due to the descriptions she gives of Mrs. Surratt and Michael O’Laughlen, but also because she took the time to sketch the layout of the court when she got home:

“This was the position of the court.

It was an interesting scene, & I am glad I went, although it is so far, & so hot.”

These diagrams are fascinating and help us solidify the placement of the conspirators and members of the military commission in the court room.

Reporting on the Execution

It is likely that the excessive heat in the courtroom convinced Ms. Wilbur that she did not need to attend the trial again. However, she did keep up with the proceedings and reported on the sentencing and execution of the conspirators (which she did not attend).

July 6, 1865:

“The conspirators have been sentenced. Payne, Harold, Atzerott & Mrs. Surratt are to be hung to morrow. O’Laughlin, Mudd, & Arnold to be imprisoned for life at hard labor, & Spangler to State prison for 6 yrs.”

July 7, 1865:

“Hottest morning yet. Martha ironed, & the whole house has been like an oven. It was too much for me. I could not work.— The days pass & nothing is accomplished— This eve. F & I took a walk.

— About 1 P.M. The executions took place in the Penitentiary Yard. A large number of people witnessed them. They were buried within a few feet of the gallows. It is all dreadful, but I think people breathe more freely now. They are convinced that Government means to punish those who deserve it. Jeff. Davis friends may feel a little uneasy hereafter.”

Unfortunately, it does not appear that Ms. Wilbur had any reaction to the death of Mary Surratt, a middle aged woman like herself. In fact the very next day Ms. Wilbur mentions walking past Mrs. Surratt’s house without any commentary.

July 8, 1865:

“Then passed Mrs. Surratt’s house on the way to Mr. Lake’s, where we had a pleasant call.”

It’s likely that Ms. Wilbur agreed with Mrs. Surratt’s fate as Ms. Wilbur was very against those who held “secesh” sympathies.

Attending Henry Wirz’ Trial

Julia Wilbur continued her habit of attending historic trials in the city, by attending the trial of Andersonville prison commandant, Henry Wirz. After Henry Wirz’ execution she once again invoked the Lincoln conspirators:

November 11, 1865:

“Called at Mr. B’s office & saw Mr. & Mrs. Belden. Heard particulars of the Execution yesterday. Mr. B. gave me an Autograph Note of Henry Wirz, a lock of hair & a piece of the Gallows. I came only for the autograph. His body was mutilated after death, Kidneys were divided among 4 surgeons. Another person had a little finger, obtained under pretense of Post Mortem examination. Remainder of body buried in Yard of the Penetentiary near Atzerot. All this, & we claim to be civilized & human! If his body had been given up to his friends, it would be torn to pieces by the infuriated people.”

As we know Henry Wirz mingled with the bodies of the conspirators until 1869, when Andrew Johnson allowed the bodies of all those executed to be claimed by family. Wirz was buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery, the same resting place of Mary Surratt.

Piece of Henry Wirz’ Old Arsenal coffin in the collection of the Smithsonian’s American History Museum.

In the Interim

By 1866, John Wilkes Booth and four of his conspirators were dead. The other four tried at the trial of the conspirators were serving sentences at Fort Jefferson off the coast of Florida. As such there was a lull for a time during which Julia Wilbur reported next to nothing revolving around the events of April 14, 1865. Only a few brief mentions exist in her diary of 1866 and early 1867.

April 14, 1866:

“Anniversary of a sad day.

Departments have been closed, & flags are at half mast. No other observance. A year ago today I was in Alex. & could not get away. It was a sad time.”

April 28, 1866:

“Went to the Army Medical Museum. Many interesting in this Museum. Called on Mrs. Smith. She is ill. Went into Ford’s Theater. Not finished yet. It is intended for archives relating to the War of the Rebellion. The sad associations connected with it will make it an object of interest for generations to come.”

April 15, 1867:

“Anniversary of Death of Abraham Lincoln! Two years have passed rapidly away.”

On visiting the National Cemetery in Alexandria on May 12, 1867:

“There is also a monument to the memory of the 4 soldiers who lost their lives in pursuit of Booth the Assassin. They were drowned.”

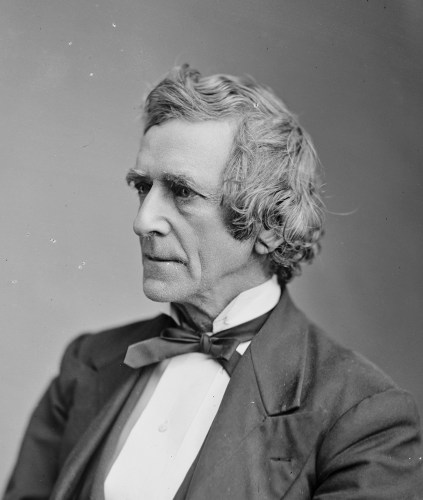

Upon seeing Secretary War Edwin Stanton on May 27, 1867:

“Saw Sec. Stanton today, but how unlike the Sec. of War that I saw in his office in Oct. ’62. He was then in the vigor & prime of manhood. Hair & beard dark & abundant. But 5 years of War have made him 20 years older. He is thin, sallow, careworn. His locks are thin & gray. I never saw a greater change in any man in so few years.”

June 21, 1867:

“On return went into Ford’s Theater to see the Medical Museum.”

The Escaped Conspirator

In late 1866, John H. Surratt, Jr. was finally captured after more than a year and a half on the run. Surratt had been an active member of John Wilkes Booth’s plot to abduct President Lincoln and take him south. His arrest in Alexandria, Egypt and extradition to the U.S., set in the motion the last judicial proceedings relating to Abraham Lincoln’s death. Once again, Ms. Wilbur would be sure to take part in this event, attending John Surratt’s trial twice and providing some wonderful detail of the courtroom scene.

February 18, 1867:

“(Surratt arrived in Washington today, is in jail)”

June 19, 1867:

“Miss Evans & I went to Mr. B’s & he went with us to City Hall & got tickets of admittance for us to the Court Room. 6 ladies present besides ourselves. Surratt was brought in at 10, & the court was opened. Judge Fisher presiding. Witnesses examined were Carroll Hobart. Vt.; Char. H. Blinn, Vt.; Scipano Grillo, Saloon keeper at Ford’s Theater; John T. Tibbett mail carrier, & Sergt. Robt. H. Cooper. Examined by Edwards Pierpoint of N.Y, Atty, Carrington.

Surratt sat with his counsel, Bradly, he, a pale slender, young man, seemed to take an interest in all that was said. His mother’s name was mentioned often, & Tibbett said he had heard her say “she wd. give $1000 to any body who would kill Lincoln.” I could not feel much sympathy for him. They must have been a bad family.

But I think Surratt will never be punished. The Government will hardly dare do it after releasing Jeff Davis.

The room outside the bar was crowded, & this is the first day ladies have been seated inside the bar.

Miss Evans was never in a Court before, & we were both much interested.”

June 21, 1867:

“Frances & Miss Evans went to Surratt’s trial”

June 27, 1867:

“Rose early. Worked till 9 A.M. Then went to Surratt’s trial at City Hall. Courtroom crowded. Judge Fisher presiding. Witnesses, 2 brothers Sowles, & Louis Weichman. He last boarded with Mrs. Surratt, was intimate with J.H. Surratt. His testimony was minute but of absorbing interest. Examined by Edwards Pierpoint. Bradly & Merrick, counsel for prisoner, are evil looking men.

Surratt looked less confident today than when I saw him a week ago yesterday.

When they were removing the handcuffs he breathed hard. Took his seat looking a little disturbed. His brother Isaac soon came & took a seat by him & they talked & laughed a few minutes.

Isaac looks like a hard case & quite unconcerned. It is very evident that J.H. Surratt was a conspirator & that the family were bad.

I would like to be here at the close of the trial, and hear the summing up.”

Unfortunately, Ms. Wilbur did not get her wish to witness the close of John Surratt’s trial. She was visiting back home near Avon, New York when the trial ended.

August 10, 1867:

“Papers from Washington.

Argument in Surratt case finished. Jury do not agree.”

August 12, 1867:

“Finished reading for Father Mr. Pierpointt’s argument in Surratt case to father. Very able argument.”

August 16, 1867:

“Jury discharged, could not agree, ([illegible]). Surratt remanded to jail.

Bradley has challenged Judge Fisher. Much excitement in W[ashington].”

Epilogue

While the period of assassination events effectively ended with the trial of John Surratt, Ms. Wilbur maintained diaries for the rest of her life. There could be more passages in her diaries commenting on or recalling those tragic days. As stated in the prior post about Julia Wilbur and the Mourning of Lincoln, Julia Wilbur’s diaries have only been transcribed for the period of March 1860 until July of 1866. All entries in this post dated beyond July 1866, were discovered by meticulously reading through the digitized pages of Ms. Wilbur’s diaries located here. There are still many discoveries to be made in Julia Wilbur’s diaries and I encourage you all to follow Paula Whitacre’s blog to read more about the work being done on Julia Wilbur.

References:

Paula Whitacre’s Blog on Julia Wilbur

Transcriptions of Julia Wilbur’s Diaries from Alexandria Archaeology

Digitized pages of Julia Wilbur’s Diaries from Haverford College

Recent Comments