The Avenger and the Actor:

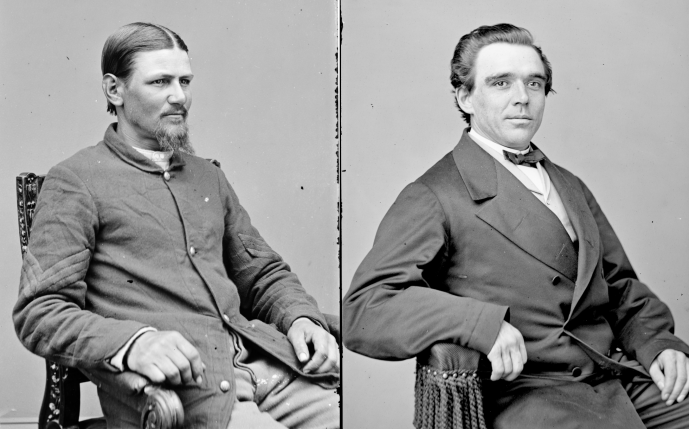

Did Sgt. Boston Corbett have an actor in his family in 1865?

By Steven G. Miller

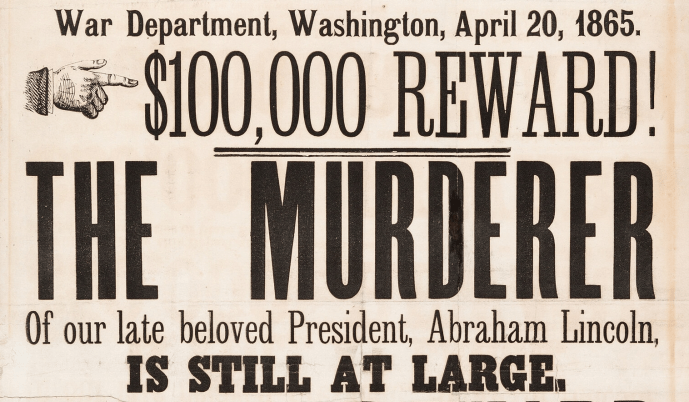

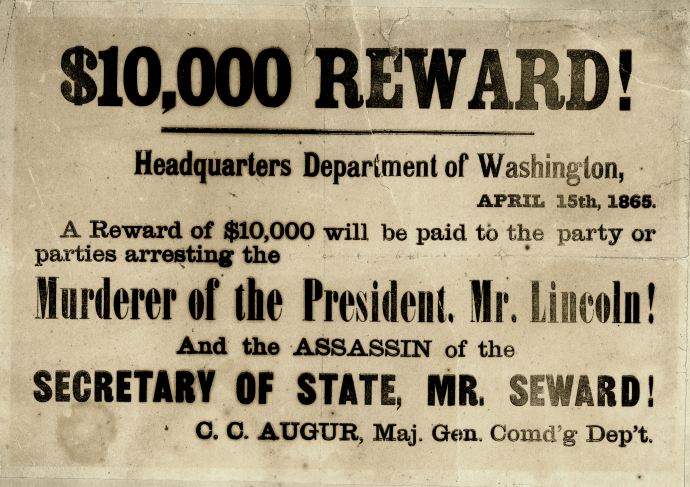

The news of Lincoln’s assassination came as a blow to many groups, both North and South, but none, perhaps, took it as hard as the theatre community. The assassin was “one of theirs” and a well-known member of the famous family of the stage. There were threats made against theatres, and actors rightly feared for their personal safety. Playhouses in Washington were closed immediately for fear of retribution, but the shock and taint of possible association with Lincoln’s killer also caused theatre owners in the country’s largest city, New York, to shut their doors temporarily.

Theatre historian Thomas Allston Brown’s 1870 History of the American Stage reported that: “The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln occurred April 14. At a meeting of the managers of the New York theatres the following day, it was decided to close all places of amusement until Wed., April 26.”[1]

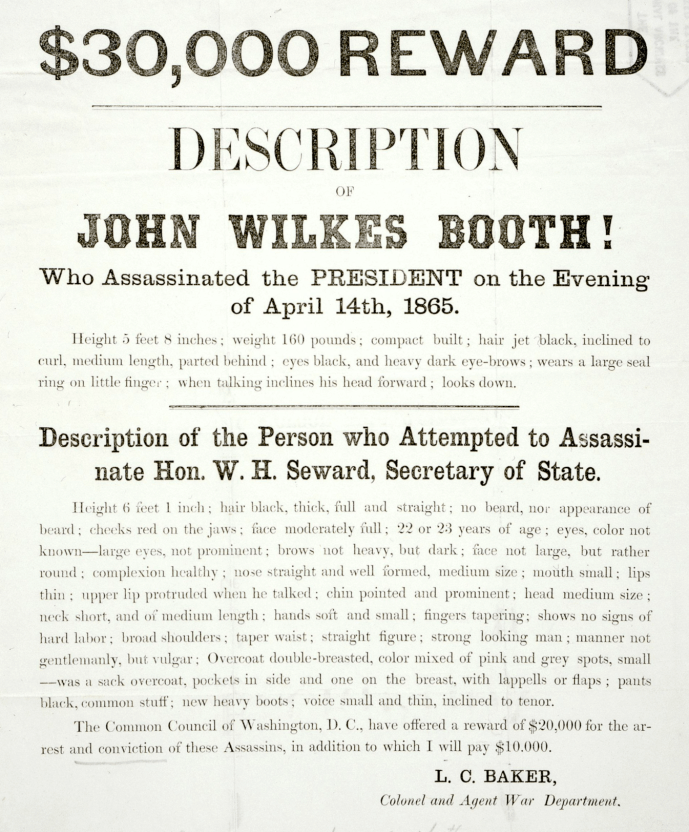

Of course, the Manhattan managers had no way of knowing that Wilkes Booth would be captured and killed on the very day they planned to reopen. In a bit of irony worthy of Shakespeare, the curtains went back up on Broadway a few hours after the assassin played out his final scene. Actors could now get back to work, but still with one wary eye on the mood of their audience.

The news broke on the 27th that Booth was dead and that the shooter, Sergt. Boston Corbett was a resident of New York City in his civilian life. On the following day, a small item appeared in the (New York) Evening Post in their entertainment news. This blurb combined a connection between the reopening of Wallack’s and the man who shot Lincoln’s assassin.

The Post stated:

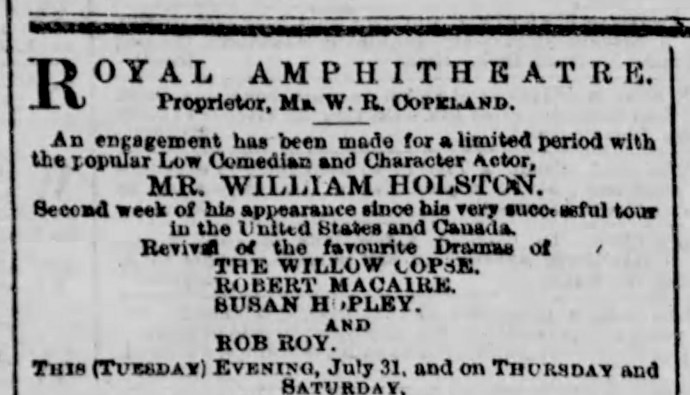

“Mr. (William) Holston, lately of the Olympic Theatre, has left that establishment, and been engaged at Wallack’s, where he will appear Wednesday night. Mr. Holston, by the way, is the cousin of that loyal soldier, Sergeant Boston Corbett, who shot the assassin Booth and is equally with him an admirer of the late President.”[2]

This snippet was overlooked in the deluge of news about the death of the president, the search for Booth, and the subsequent trial of the Conspirators. It was only recently rediscovered, and this is likely the first mention of it in over 160 years.

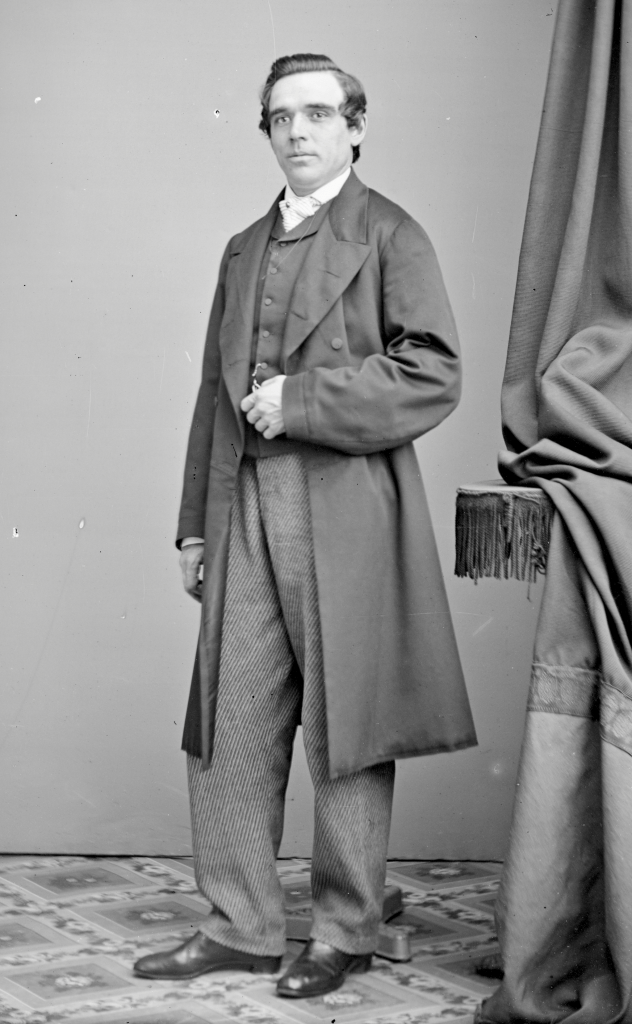

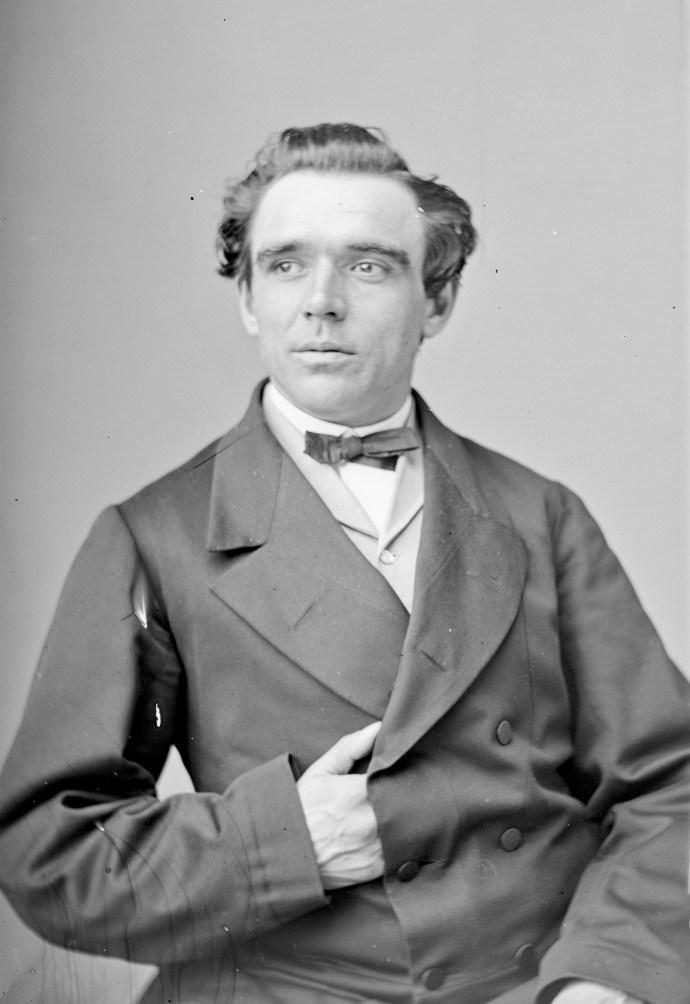

Who was the actor Holston?

William Holston was a comedian and character actor who was gaining popularity in America in 1865. He was born in Camden, England, in 1830. Stage historian Brown wrote of him in 1870:

“HOLSTON, WILLIAM—This English actor made his debut in London, Eng. Sept. 15, 1856 at the Lycian Theatre as Blocus in “Perdita, or the Royal Milkmaid,” he came to America and appeared with considerable success at the Olympic and afterwards at Wallacks’ Theatre. Returned to England, where he is at present.”[3]

Was Holston related to Sgt. Boston Corbett? If so, how?

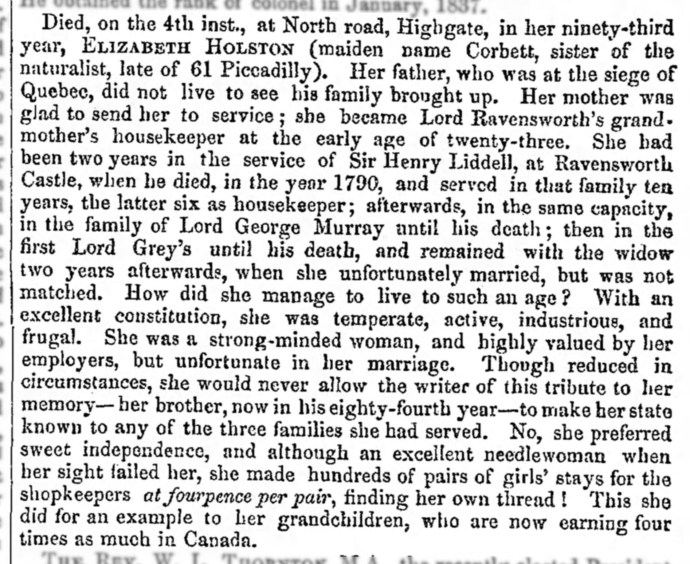

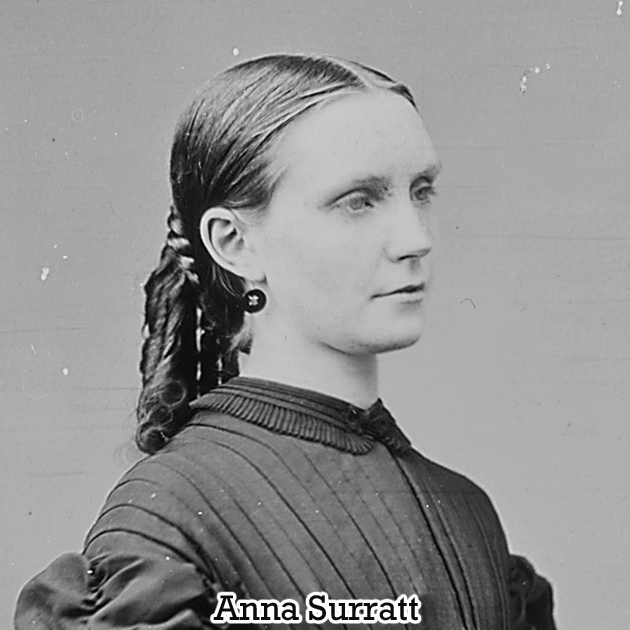

In March 1865, Boston’s father, Bartholomew Corbett, who was living in London, wrote a tribute to his older sister, Elizabeth, who had recently died. This piece was widely reprinted, usually under the headline, “An Extraordinary Yorkshire Woman.” Of the eighty-plus reprintings of this article – throughout the British Isles, various parts of the Empire, or American cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston – the author of the piece is usually not identified. In one, however, he is: Her obituary lists her as, “ELIZABETH HOLSTON (maiden name Corbett, sister of the naturalist, late of 61 Piccadilly).” 61. Piccadilly was the long-time location of “Corbett’s Natural History Museum.”[4]

My research into the Corbett family shows that Elizabeth Corbett married a tailor named James William Holston, who preceded her in death. The actor, however, was her grandson. His parents were James W. Holston, Jr., and his wife, Harriet. William Holston’s grandmother was Boston Corbett’s aunt. In other words, William Holston was Boston Corbett’s first cousin once removed.[5]

Were Boston and William in contact?

This is unclear, but it’s highly unlikely that they were. Obviously, William was aware of his cousin, and they were both in Manhattan between 1865 and 1870, but there is no mention of Holston in any of Corbett’s papers or any additional newspaper articles.

Corbett’s puritanical attitude would have made any communication uncomfortable, at best. His beliefs were discussed in an untitled article in the Cincinnati Enquirer, October 7, 1886. It referred to “a letter Boston Corbett is said to have written to an old comrade who had proposed to give a public entertainment upon an intense episode of the civil war.” “Keep out of the theater,” writes Corbett to his friend. “If Lincoln had never gone to the theater he would not have lost his life. Most of those who go there lose life, and soul, too.”

Another obvious question arises: Did Holston appear on stage with any members of the Booth family? There is no evidence he did, but Holston was in an 1870 performance in Baltimore which was co-produced by Edwin and Wilkes’ brother-in-law, John Sleeper Clarke. The New York theatrical paper, the Clipper, reported it:

“Of Baltimore Dramatic Affairs,” New York Clipper, March 26, 1870.

“Our correspondent, under date of March 18th, thus discourses: — Manager Ford, of the Holliday Street Theatre, has been delighting his patrons during the week with the resumption of specie payment and a trip to the great city of London at a very nominal charge. The “Lights and Shadows of the Great City of London,” as witnessed by so many Baltimoreans up to date, consists of a series of paintings of high excellence and fidelity to nature, executed by John Johnson, of London, and illustrating the prominent public buildings, squares, bridges, etc., of that metropolis. In conjunction with these views is a thrilling and emotional drama, the joint production of Henry Leslie, of London, and John S. Clarke, of Baltimore. The cast, an unusually strong one, is as follows: . . . William Holston, of England (first appearance), as Ralph Heron.”

Was Sleeper aware of the connection? Did Bos’ know of it? Is the answer buried out there in a newspaper archive waiting to be ferreted out? We may never know.

Just as a matter of interest, I became curious as to what Holston might have been up to on April 14th and 15th. Was he in preparation for the opening of the play at Wallack’s? Or, was he already engaged? It turns out that Holston was performing at The Olympic, as hinted at in the notice of his family connection to Sergt. Corbett. Both the Tribune and the Daily Herald mentioned it.

The blurb in the Tribune on April 15th said:

“Olympic Theater. “London Assurance” will be represented this afternoon for the least time at the Olympic during the present season. In the evening Mr. W. Holston’s benefit will take place. He is announced to appear in two parts which have elsewhere gained him much reputation—those of Jabe Bunny in “Black Sheep” and Daddy Hardacre, in the piece of the same name.”

An advertisement in the Daily Herald of the 14th lists a Saturday matinee for “London Assurance” and the evening “benefit of Mr. Holston.” Undoubtedly, the Saturday performances were cancelled, and Mr. Holson’s benefit, which would depend on ticket sales, was another victim of Booth’s attack. Perhaps he found some small comfort in knowing that a relative was responsible for killing the assassin responsible for the crime perpetrated on the American nation, Holston’s profession, and his personal finances.

What happened to Holston after 1865?

Holston travelled between America and England between the years 1865 and 1874. He appeared on the stage in New York, London, Newark, NJ, Springfield, MA, and Liverpool.

In 1874, he joined a theatre troupe that travelled to India for a series of engagements.[6] While there, unfortunately, his health took a dramatic turn for the worse. The record of what happened is not clear. He returned to England to recuperate, and on August 26, 1875, the New York Tribune reported:

“Mr. William Holston—an actor who won many admirers by his comical eccentricity when he was at Wallack’s—has been dangerously ill in Calcutta. He is now in retirement after a perilous surgical operation; but hopes are entertained that he will recover his health.”

His health did not get better, however, and he died on January 21, 1876. The Liverpool Intelligence lamented, “Mr. William Holston, well known both to metropolitan and provincial theatre goers as an excellent actor in character died in London last Friday.”[7]

Conclusion:

From the evidence that has surfaced, it appears that Boston Corbett, the soldier who shot Lincoln’s assassin, was related to William Holston, an actor who was scheduled to appear on stage in New York City in April 1865. Holston’s premier was delayed by the tragic news that Lincoln had been attacked in a theatre by a well-known actor. William Holston was the first cousin once removed to Corbett, and let it slip to a drama reporter that he was connected to the avenger. Later on, Holston appeared in a play that was stage-managed by Booth’s brother-in-law, John Sleeper Clarke. Holston doesn’t appear to have mentioned the connection to Cousin Boston again and, perhaps, wisely chose not to reveal his relationship to members of the Booth family.

[1] Brown, Thomas Allston, History of the American Stage; Consisting of Biographical Sketches of Nearly Every Member of the Profession that has appeared on the American Stage from 1733 to 1870. NY: Dick and Fitzgerald, 1870, pg. 255.

[2] Untitled, New York Post, April 28, 1865.

[3] Brown, ibid., pg. 182.

[4] “Obituary,” Morning Examiner (London, England), March 11, 1865.

[5] Bartholomew Corbett (1781-1866) and Elizabeth (Corbett) Holston (1772-1865) were siblings. Thomas (later, Boston) was the 4th of 5 children born to Bartholomew and Elizabeth (Wild) Corbett. Elizabeth (Corbett) Holston and her husband, James Holston (1781-1857), had 3 children. Their son, James William Holston (1810-?), was the father of William Holston (1830-1876), the actor. In other words, the actor was the first cousin once removed to Boston/Thomas Corbett.

The preceding information was gleaned from Ancestry.com, FamilySearch, and the records of Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, among other sources. Much of the material was published in Miller, Steven G., “Pursuing the Mysterious Family of Thomas (Boston) Corbett,” Lincoln Herald, Volume 118, Number 4, Winter, 2016.

Note: It’s tricky to keep all of the members of the family who were named Elizabeth straight. For instance, Boston (Thomas) was the son of Elizabeth Corbett. His aunt was Elizabeth (Corbett) Holston, and Boston even had an older sister named Elizabeth!

[6] An article titled “The Rise and Fall of the Calcutta Stage,” by “Mr. Dangle,” appeared in The Theatre magazine, Vol 1, No. 1, page 90. It discussed the efforts to bring a theatre company to India during 1874 and later. Called “The Corinthian Theatre Company,” it was organized by Mr. G. B. W. Lewis. The upshot of it was that “Mr. E. English arrived in Calcutta with a comedy and burlesque company, (which) contained the following artists… William Holston.”

[7] “Death Mr. Wm. Holston,” Liverpool Intelligence, January 26, 1876.— Mr. William Holston, well known both to metropolitan and provincial theatre goers as an excellent actor in character died in London last Friday.”

My deepest thanks to my friend Steve Miller for this excellent piece. You’re the best, Mr. Steve.

Recent Comments