I’m so pleased to welcome another guest contributor to LincolnConspirators.com. The following piece was written by Joe Barry, a historical researcher currently working on a book about Joseph B. Stewart. On April 14, 1865, Stewart was seated in the front row of Ford’s Theatre, taking in the play. Stewart heard the sound of a gunshot and witnessed a man jump from the Presidential box to the stage below. While the rest of the audience remained frozen in their seats in confusion, Stewart was the first to take action. The D.C. lawyer, noted as one of the tallest men in Washington, climbed over the orchestra pit, onto the stage, and gave chase to the assassin. Joe Barry has spent the last few years uncovering many more interesting stories in the life of Joseph Stewart, a man he describes as the Forrest Gump of the 19th century. Having already previewed one of Joe’s chapters about the assassination, I’m very much looking forward to seeing the final product in the near future. You can learn more about Joe and his upcoming book by checking out his website JoeBarryAuthor.com.

Will Research for Peanuts!

By Joe Barry

Joseph Burroughs holding John Wilkes Booth’s horse, from the May 13, 1865, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated

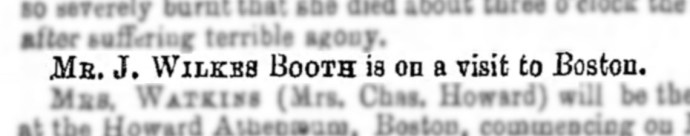

One of the more enigmatic figures of the Lincoln assassination is Joseph “John Peanuts” Burroughs, the young errand boy at Ford’s Theatre who held John Wilkes Booth’s horse prior to the assassin’s escape. Burroughs’s age is unknown, although estimates vary between fourteen to seventeen years old. In his statement to Justice Abram Olin on April 15, 1865, his name was dictated as Joseph Burrough. However, the conspiracy trial records also list Borroughs, Burrow, and John C. Bohraw—which are likely phonetic transcription errors. At the theater, he soon earned the nickname “John Peanuts” because he peddled peanuts in between acts. Some newspapers after the assassination even misreported “John Peanuts” as “Japanese.”[1]

Burroughs’s experience in the assassination was brief and traumatic. After Booth asked for the stagehand Edman “Ned” Spangler to hold his horse, Spangler begged off owing to his scene shifting duties, and the task fell to Burroughs. After approximately fifteen minutes, Booth burst through the back door into Baptist Alley and rewarded Burroughs’s loyalty by hitting him on the head with the butt of his knife and kicking him away from his horse. Across Peanut’s multiple pieces of testimony, he described handling horse-related duties for Booth over the previous few months, of working with Spangler in fixing the president’s box at Ford’s Theatre, and of Spangler cursing the president over the war.[2]

Throughout the years, a consensus emerged that Burroughs was Black and dull-witted. The best evidence indicates he was neither. Burroughs signed his second statement on April 24th with an “X”, which could suggest he was illiterate, but his testimony reveals he was intelligent, articulate, and well-versed with horses. The orchestra director, William Withers, and former police superintendent, Almarin C. Richards, both described him as Black, but these accounts were decades old. More conclusively, the trial transcripts for Burroughs lack the “(Colored)” description preceding his name in keeping with the discriminatory practice of the period. John F. Sleichmann, the assistant property manager at Ford’s Theatre, testified that Booth, Burroughs, and a few others shared drinks at the nearby saloon on the day of the assassination. Yet, Blacks were not allowed to sit down in such restaurants at this time, and an inveterate racist like Booth would not associate with a Black person. Nevertheless, contemporary newspaper illustrations depicted Burroughs as Black.[3]

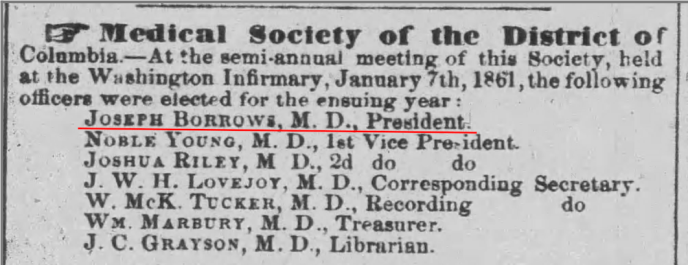

In American Brutus, Michael Kauffman theorizes Burroughs was the son of Doctor Joseph Borrows, III, a prominent physician in Washington, D.C. In his April 24th statement, Burroughs stated he was living with his father at 511 Tenth Street. Although this corresponds to the Ford’s Theatre address since at least 1948, prior to 1869, this address was south of Pennsylvania Avenue near the present-day block of 317-337 Tenth Street NW. The address for the Army Medical Museum in 1868 (housed within the theater building) was 454 Tenth Street. Notably, the city directory listed Dr. Borrows’s address as 396 E Street north, which abutted Baptist Alley behind Ford’s Theatre. The Borrows name and his close proximity to the theater make for a compelling connection—even if it does not illuminate Burroughs’s subsequent actions and movements.[4]

However, the Dr. Borrows theory has shortcomings. The reference to Peanuts living with his father implies the mother was absent. Yet, Dr. Borrows had a wife, Catherine, who outlived him. Further, the 1860 census for the Borrows household includes four females, but no son. Tragically, Catherine delivered a stillborn boy, Joseph, in 1850—a year after their five year-old daughter died. As author Susan Higginbotham has noted, a doctor’s son would be in school and not selling peanuts and running errands at a theater.[5]

Even still, Dr. Borrows’s obituary in 1889 provides a clue that may explain a potential connection with Peanuts. The doctor was an eminent physician who served for several years as president of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia. His obituary in the Evening Star notes: “There was probably no more popular physician or man in the District than Dr. Borrows, and hundreds of children were named for him in families he attended through, in some instances, four generations.” It is possible Burroughs received assistance from Dr. Borrows and perhaps even stayed at his residence in the same itinerant manner as at Ford’s Theatre. Similarly, Ned Spangler kept a boarding house for supper but mostly slept inside Ford’s Theatre.[6]

Dr. Joseph Borrows was a leading Washington, D.C physician, Daily National Intelligencer, January 9, 1861

Along similar lines of a father-figure role, Thomas Bogar, author of Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination, posited in Roger Norton’s Lincoln Discussion Symposium that Ford’s Theatre stage manager John Burroughs Wright might have semi-adopted Joseph Burroughs and gave his middle name as Peanut’s surname. In 1915, Wright’s wife, Annie, referred to Peanuts as “a simple minded but good natured street waif who worked all day and half the night about the stage.” The Wrights lived at the Herndon House on the corner of F and Ninth streets, only one block to the rear of the theater. (This is the same building Lewis Powell stayed at, and where Mary Surratt called on him.) If the Wrights did play the role of surrogate parents, it was not enough to keep Peanuts from roaming.[7]

After the assassination, Burroughs was deterred from providing a statement to the police due to the mob accusing anyone entering or departing the police station of being a conspirator. Burroughs had to be especially cautious once it became known he had held Booth’s horse, and one eyewitness recalled a policeman escorting Peanuts into the station. No parental figure appeared on his behalf.[8]

More proof of Burroughs’s independent wanderings is found in Judge Advocate Henry L. Burnett’s May 9, 1865, letter to Colonel Lafayette C. Baker relaying Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s order “that the boy Peanuts be placed in confinement in some comfortable place that he may be forthcoming when wanted.” Again, if Burroughs had the protection of his parents and a permanent roof over his head, he would have been readily available for questioning and not require government quarters. Regardless, Burroughs avoided any further statements or publicity after his conspiracy trial testimony.[9]

The key question in tracking down Peanuts is whether he stayed in Washington, D.C. or left the capital. To this end, researcher Steve Williams has found an intriguing lead on a Joseph Alexander Burroughs from the Tenleytown D.C. suburb and of the correct age to be Peanuts. This Joseph Burroughs was listed as a farmer, married Mary Elizabeth Burroughs in Washington, D.C. in 1873, and moved to Baltimore shortly thereafter. After settling in Baltimore, this Joseph is listed as a laborer —thereafter a produce seller—and favored the Burrows surname. Joseph and Mary had three daughters and two sons. Of note, he was definitely literate, and his son, Joseph Cornelius, readopted the Burroughs surname. Joseph Burrows died in Baltimore in 1931.[10]

If Peanuts is not this Joseph Burroughs from Tenleytown, then he likely departed Washington, D.C. before the 1870 census. Bogar correctly notes Burroughs and the other backstage employees had highly transferable skills to find jobs in any city. In the frequently shortened lifespans of the nineteenth century, it is also possible he died early. If Burroughs had a family, he bucked the trend of those associated with the assassination to have their (often highly exaggerated) exploits published in their obituaries. Given the trauma of being an unwitting accomplice to President Lincoln’s assassination, it is understandable if, for the remainder of his life, Burroughs simply wanted to be left alone.[11]

In the decades following the assassination, “Peanuts” resurfaced in random locations, including Washington, D.C., New York, and Massachusetts—but these sightings seem spurious. In 1887, a Louisiana newspaper mentioned Peanut John was living in Shreveport and was known as “Mixie.” In 1930, an elderly Black man appeared at a Washington, D.C. fire station and showed a scar on his head supposedly from Booth’s knife. A formerly enslaved man named Nathan Simms told a tall tale of being John Peanuts and actually helping Booth dismount outside of Surratt’s Tavern later that night. In 1960—twenty six years after Simms’s death—the Boy Scout Troop of Marshallton, Pennsylvania, raised money for a gravestone that told his story. In 1980, A. C. Richards’s biographer, Gary Planck, cited the naturalist John Burroughs as Peanuts.[12]

The most colorful Peanuts imposter was an unwilling participant: a diminutive street person of Italian descent named Joe “Coughdrop” Ratto who sold cough drops near Ford’s Theatre. Local residents taunted him mercilessly, asking if he had held Booth’s horse—which would throw him into a violent rage. Stories of Ratto emerged as early as 1909, and likely fed follow on narratives that John Peanuts was Italian. An imaginative account from 1923 claimed the Italian ambassador helped free him from prison after the assassination, in which Peanuts returned the favor by serving in the Italian Army.[13]

It need not be highlighted each theory relating to Joseph “John Peanuts” Burroughs relies upon healthy doses of speculation. With multiple names, a single address, and a publicity-shy witness who faded into history, we have limited material to work with. Indeed, the renowned researcher James O. Hall assembled a file on Peanuts, and on the outside cover summarized his findings: “I was never able to trace the boy.” In the end, we are left with the same plea from the Surratt Courier in 1989: “Will the Real ‘Peanuts’ Burroughs Please Rise?!”[14]

[1] The official record of the commission compiled by Benn Pitman lists the name as Joseph Burroughs. The conspiracy trial transcripts show multiple references to Peanut(s), John Peanut(s), and Peanut(s) John. Michael Kauffman also cites Bohrar and Burrus in American Brutus. “The Assassination,” Daily Illinois State Journal, April 22, 1865, p. 1.

[2] Peanuts stated he held the horse for fifteen minutes at the conspiracy trial, although this is different from his provided statements. Burroughs’s testimony at the conspiracy trial is found at Edward Steers, Jr., ed., The Trial: The Assassination of President Lincoln and the Trial of the Conspirators (Lexington, Kentucky, 2003), 187-95, 465-66; William C. Edwards and Edward Steers, eds., The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence, (Champaign, Illinois, 2009), 238;

[3] William J. Ferguson’s 1930 memoir I Saw Booth Shoot Lincoln refers to Peanuts as “dull-witted.” Joan L. Chaconas, “Will the Real ‘Peanuts’ Burroughs Please Rise?!” Surratt Courier (June, 1989), 1, 3-7; “Wilkes Booth Again,” Critic (Washington, D.C.), April 17, 1885, p. 1.

[4] Washington, D.C. addresses changed to a new format in 1869. William H. Boyd, Boyd’s Washington and Georgetown Directory, 1868 (Washington, D.C., 1868), 40; Edwards, Steers, The Lincoln Assassination, 463; Andrew Boyd, Boyd’s Washington and Georgetown Directory, 1865 (Washington, D.C., 1865), 142.

[5] “More on the Elusive Peanuts,” Surratt Courier (September, 2014), 11; 1870 US Census, Washington, D.C., Ward 3, family 220; “Dr. Joseph Borrows,” Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/140486080/joseph-borrows.

[6] Emphasis added. The Ned Spangler information is from Jacob Ritterspaugh’s testimony. “Dr. Joseph Borrows Dead,” Evening Star, May 31, 1889, p. 3; Steers, The Trial, 394.

[7] The thread for this theory is found at: https://rogerjnorton.com/LincolnDiscussionSymposium/thread-1802.html. “She Saw Lincoln Shot,” Boston Globe, April 11, 1915, p. 66; Thomas A. Bogar, Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination: The Untold Story of the Actors and Stagehands at Ford’s Theatre (Washington, D.C., 2013), 88; Trial of John H. Surratt in the Criminal Court for District of Columbia, Hon. George P. Fisher Presiding, (2 vols., Washington, D.C., 1867) I, 235; Louis J. Weichmann, A True History of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the Conspiracy of 1865 (New York, 1977), 121-22.

[8] “Lincoln’s Assassination,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Dec. 3, 1891, p. 12.

[9] Edwards, Steers, The Lincoln Assassination, 259-60.

[10] Substantial documentation for this potential Burroughs is in the same above Lincoln Discussion Symposium link.

[11] Bogar, Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination, 276.

[12] Chaconas, “Will the Real ‘Peanuts’ Burroughs Please Rise?!” Opelousas Courier (Opelousas, Louisiana), April 2, 1887, p. 1; Peanuts Folder, James O. Hall Research Center, Clinton, Maryland; Edward Steers, Jr., Lincoln Legends: Myths, Hoaxes, and Confabulations Associated with our Greatest President (Lexington, Kentucky, 2007), 319-22; Gary R. Planck, “The Lincoln Assassination: The ‘Forgotten’ Investigation, A. C. Richards, Superintendent of the Metropolitan Police,” Lincoln Herald, 82 (Winter 1980), 526.

[13] A. C. Richards later referred to Burroughs as Italian in 1906, likely stemming from the Joe Ratto lore. “Did ‘Coughdrop Joe’ Ratto Hold Booth’s Horse?” Lincoln Lore, 1571 (January, 1969), 2-3; “People Met in Hotel Lobbies,” Washington Post, Jul. 14, 1909, p. 6; C. W. S. Wilgus, “The Lincoln Tragedy,” Ravena Republican (Ravena, Ohio), April 19, 1906; “Brooklyn Man was in Theater Night Lincoln Was Shot,” Brooklyn Eagle, Feb. 11, 1923, p. 36.

[14] “Peanuts” folder, James O. Hall Research Center; Chaconas, “Will the Real ‘Peanuts’ Burroughs Please Rise?!”

Recent Comments