During the months of April, May, June, and early July 1865, the front pages of the nation’s newspapers contained headlining information about the assassination, search, trial, and fate of the conspirators. Newspapers from across the nation sent correspondents to Washington to attend the trial of the conspirators in order to take down testimony and comment on the accused. With so many newspapers covering the same material, the big city newspapers found it necessary to differentiate their coverage to attract more readers. The Philadelphia Inquirer sought to set themselves apart by including engravings in their coverage of the events.

While newsworthy events had been photographed as early as the invention of the camera, it was impossible to reproduce the photographs in a newspaper until the 1880’s. Instead, photographs or drawings of events would have to be turned into engravings, a laborious and time consuming process, before they could then be printed alongside text. There were special illustrated magazines like Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine that had pages filled with such historic engravings, but these were only published on a weekly basis. Additionally, the amount of time it took to create and complete a quality engraving of an event was about a week and a half, causing a measurable delay between an event and a published engraving of it. Harper’s Weekly, for example, didn’t report on the assassination of Abraham Lincoln until their April 29th, issue because that is how long it took them to produce engravings of the characters and events.

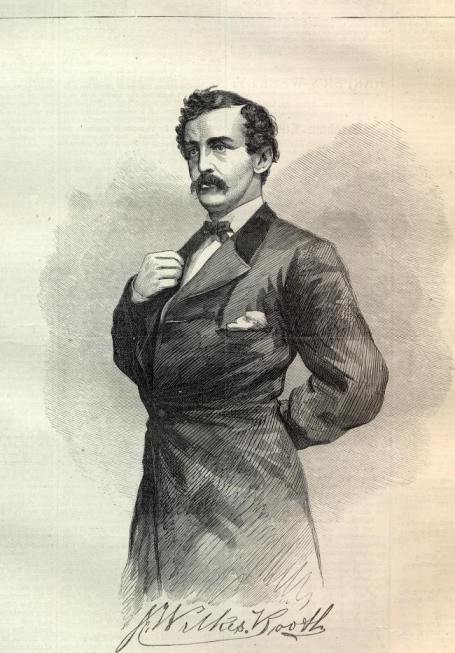

The first engraving of John Wilkes Booth that appeared in the April 29th, 1865 issue of Harper’s Weekly.

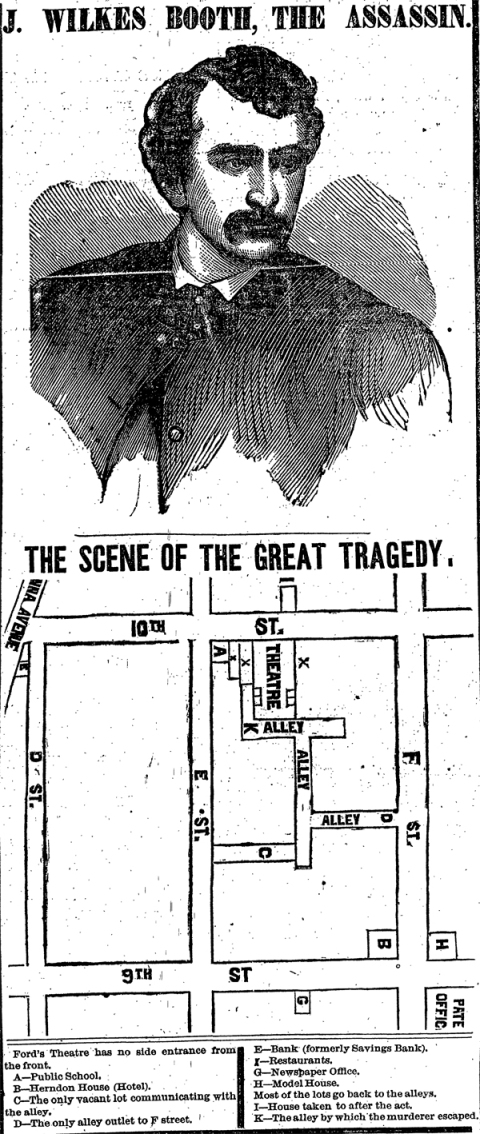

The more detailed the engraving was, the longer it took to make. As a daily newspaper, The Philadelphia Inquirer could not afford the time or money it would take to create incredibly detailed engravings to supplement their coverage of the trial. Instead they produced and published the following very basic engravings:

April 17th, 1865:

April 28th, 1865:

May 5th, 1865:

May 13th, 1865:

May 19th, 1865:

May 20th, 1865:

May 22nd, 1865:

June 26th, 1865:

June 27th, 1865:

There are a few more engravings of people like Jefferson Davis and Lafayette Baker that I haven’t put up here in the interest of space and focus. I’m sure several of you are thinking, “I don’t have those newspapers, but I’ve seen those before.” For one, I have most of the above conspirators’ engravings in their respective Picture Galleries. However, practically all of these pictures were also published in a book that was advertised in The Philadelphia Inquirer on July 10th, 1865:

Once the trial of the conspirators was over, there was a race to see who would be the first to publish the transcript of the trial in book form. The nation had been following the trial daily in the papers and there was money to be made by the first publisher who could provide a permanent book version of it. The publisher T. B. Peterson and Brothers was the first to bring a trial transcript book to the market debuting it only three days after the execution of four of the conspirators. Peterson’s edition is called, The Trial of the [alleged] Assassins and Conspirators at Washington City, D.C., May and June, 1865, for the murder of President Abraham Lincoln. The swiftness of this publication was due to the cooperation Peterson received from The Philadelphia Inquirer. Essentially, the Peterson copy of the trial is a direct copy of The Philadelphia Inquirer‘s coverage of the trial in book form. They acknowledge this on the first page of the book stating that, “The whole being complete and unabridged in this volume, being prepared on the spot by the Special Correspondents and Reporters of the Philadelphia Daily Inquirer, expressly for this edition.” Along with the text, Peterson included the Inquirer’s engravings above.

Though not a verbatim account as it was advertised, the Peterson version of the trial provides unique details not found in the other two editions of the trial. Peterson copied over the Inquirer reporters’ accounts of the courtroom and the little asides and actions of the conspirators during the proceedings. Though Peterson’s edition is the low man on the totem pole when it comes to use in research, those courtroom gems and the engravings still make it worth reading and consulting from time to time.

There is, however, one engraving from the Inquirer that I posted above that did not make its way into Peterson’s book. It is this engraving of “Samuel C. Arnold”:

I can understand why Peterson did not include this engraving. It looks nothing like the real Samuel B. Arnold. At first, I just assumed it was a bad engraving from a poor artist (not unlike another questionable image of Sam we’ve discussed previously). However, when compared with the engraving of John Surratt from the wanted poster, it appears that was supposed to be the subject all along:

It seems clear that the engraver used this image of John Surratt as his guide. Though flipped, the hair, features, and clothes match perfectly. Whether this misidentification occurred during the printing of the newspapers or before then, I cannot say. Regardless, it appears that Peterson noticed the discrepancy before publishing his edition of the trial and scratched the engraving entirely.

Photojournalism is something we take for granted today. Back in 1865, however, it took an immense amount of time and effort to provide readers with visuals to complement the written word.

References:

The Philadelphia Inquirer Online Civil War Collection

The Trial of the [alleged] Assassins and Conspirators at Washington City, D.C., May and June, 1865, for the murder of President Abraham Lincoln by T. B. Peterson and Brothers

Have never noticed that the engraving was of John/Issac Surratt; definitely NOT Arnold in any way, shape or form! There has always been a discrepancy as to whether or not that photo was of John Jr. or Issac….I’ve heard both ways – Anyone ever determine for sure?

Great post as always, Dave!

While we discussed the Surratt wanted poster image before, we couldn’t conclusively say one way or another. Personally, I side with Father Keesler and the evidence he espoused: http://boothiebarn.com/2012/08/11/surratts-wanted-photo/#comment-453

Fantastic, Dave. Yes, I have to agree with Good “Father K” myself then….he knew Surratt alright! Thanks!

Did Dr. Mudd ‘s engraving fall off somewhere?? lol

That’s a great observation, Donna. Perhaps the Inquirer didn’t think he looked menacing enough to draw.

This reminds me of how Dr. Mudd is also not included in the “Ring of Conspirators” in Pitman’s version of the trial. The Dr. Samuel Mudd Research Site has a great letter regarding that: http://www.samuelmudd.com/the-accused.html

I have discovered a newspaper articles preserved in glass in an attic. It is the philadelphia inquirer, April 17, 1865. It has the same picture and markings as the ones at the top of the this page. Can I determine authenticity. It is not is great shape, but certainly readable.

Thanks,

I’m afraid I’m no newspaper expert and I can’t offer you much in the way of authenticating it. You might want to consult Rick Brown at HistoryBuff.com. He’s a big newspaper guy with a strong interest in the Lincoln assassination. Hopefully he can help you.